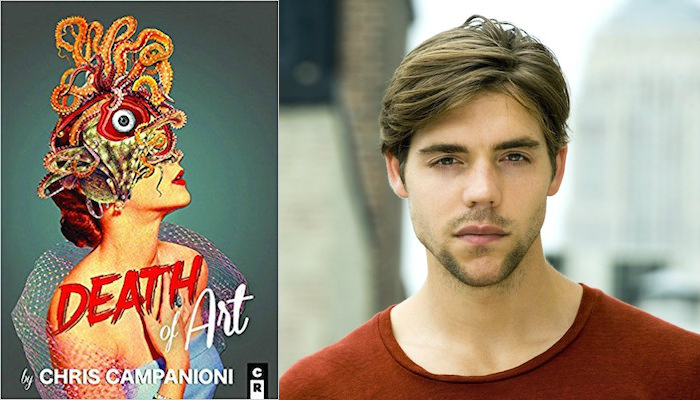

Chris Campanioni’s new book is Death of Art (C&R Press). His recent work appears in Ambit, Gorse, Hotel, Whitehot, and RHINO. He is a Provost Fellow and MAGNET Mentor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he is conducting his doctoral studies in English. He edits PANK, At Large, and Tupelo Quarterly and teaches literature and creative writing at Pace University and Baruch College.

¤

KRISTINA MARIE DARLING: Your recent hybrid text, Death of Art, moves gracefully between genres. What begins as an essayistic experiment gives rise to lines of verse, white space, and perfectly timed ruptures. I’d love to hear more about the relationship between these different literary forms in your work. What does this movement across genres make possible for you — as a thinker, as a cultural critic, and as a storyteller?

CHRIS CAMPANIONI: I like that you began with the phrase essayistic experiment because we tend to forget, I think, the meaning of essay as an attempt, an endeavor, an experiment. To try, without knowing what will happen except to trust the process itself as a poetics of uncertainty. To that end, I also think that this white space, these ruptures, are only possible through the rapid passage between genres, until one arrives, as if by accident, at a liminal threshold, something uncategorizable and better for it. So it’s that interplay between text and its performance through choreography — how it’s arranged in sequence with everything else that it rubs up against, collides with, merges. These interruptions or eruptions can often mimic the jump cuts or dissolves of cinema — a constant now-ness or the shock of awakening — but outside the text, they also create gaps for readers to embody. I want more and more to make a travel book — a book that travels, permutates, collapses but also unfolds as the reader moves along and inside. When I look back at old notebooks I am reminded of an instructor who told us, I think, that you should never be able to re-arrange the chapters in your novel. And I feel it’s just the opposite. If I can’t re-arrange the sequence of pieces in a manuscript, if I can’t continue to re-arrange them, I know I’ve done something wrong, because the process of poetic production should not end in the book but begin in one. Each page should be interchangeable with any other page.

What are your hopes for the reader’s experience of the text as they read — and after the book has closed?

I would want them to participate. The way I felt myself implicated in the writing of works by Cortázar, Perec, Queneau, Cabrera Infante. Literature should be an experiment but also a game; intellectual pursuits and pleasure should coexist in the body of the text and I think our role as authors and artists is to bring about that synthesis. I think there’s this tendency — not just in literature but also in academia — in which pleasure can’t hold court in the halls of serious intellectual endeavors, but I think it’s just the opposite. In fact, I really believe a work of art must always originate in pleasure for it to transmit its intellectual concerns effectively, and vice versa. It’s almost an instance of burlesque or parody to consider that essayistic experiment that instigates Death of Art, because although the plot point — removing my face from every single photograph, exhibiting the reproduced heads or head-less torsos as an art installation — propels the book forward, the actual project completely stalls, withdraws, abandons itself in the text. Instead it functions as an excuse or attempt — an essay — to perform the kind of cultural theory I was concerned with.

In the spring, I received a generous grant from the City University of New York’s Office of Educational Opportunity & Diversity Programs to assist me with my research in the social and political urgency of personal, often hybrid texts for marginalized communities. The chapter I wrote, structured as letters written to Walter Benjamin, whose exile I was following, illustrates well, I hope, what exactly I would wish for readers who approach my work:

The point of true progression — isn’t it Walter? — is for the work to remain, always, a work in progress. Dear Walter, any time I write anything, I want it to be read as if it were being written at the moment one reads it, and their contact constitutes another marker or waypoint on the map, that expands to meet their gaze, and also contracts, focusing on a piece or part so as to get closer.

Dear Walter, the point isn’t satisfaction, it’s penetration. It’s the moment before I finish that I want to die.

You’ve also published a novel, as well as literary criticism, and an array of traditionally lineated poems, in literary journals. What first drew you to hybrid forms, and what kept you engaged in this conversation?

I’m hungry; I want too much and all the time. I think it’s my being raised by two immigrants and what my parents each instilled upon me, consciously or not, in terms of want. I began by writing novels because I wanted to invert the hierarchy of story and plot to focus on reader experience and the experience of reading but novel writing began to bore me because everything still seemed too technical, too systematic, too familiar. I could try — and certainly many other writers do — to re-evaluate generic conventions of the novel, but in the end, certain conditions must still be met. A story must have been told, something must have changed. Put another way, novels set up rules which determine character and situation. I wanted out of that sort of literary determinism. Poetry has always been far more exciting and ecstatic to me because of its absence of limits—in fact, what makes poetry so powerful is its porousness, and the possibility that comes with it—and as I continued to write in various modes—lineated poems, short stories, essays—I knew I could not effect a level of intellectual discourse unless I combined all of them into one text, and eventually, one piece.

In another sense, as a first-generation Cuban- and Polish-American, I’ve always written in response to my neo-mestizo experience, in and out of my art, and hybrid writing has become an endeavoring toward tracking these poetics in real-time, and positioning the results toward and against the academy. My conception of hybrid critical/creative writing is as a growing, living document and testament to the avant-garde among and between our marginalized communities which have, historically, been left out of the avant-garde conversation. Hybrid forms have allowed me to synthesize those many different, often intersecting modes of writing but also their objectives, into a single work. I think more and more writers are working toward a poetics of hybridity in search of that kind of totality and at the same time, uncertainty. Like: a gathering of the point and the whole, which of course should be read two ways.

Your book shows us, subtly and skillfully, that some insights — about mass culture, time, and the aesthetic imagination — are simply not communicable in more traditional forms of writing. What limitations do genres — and their received conventions — impose upon our thinking, the narratives we create about ourselves, and our experience of the world around us?

Susan Sontag wrote in one of her many notebooks that she disregarded the separation, a dogma, she said, between the essay and fiction. I think any time we — as researchers, writers, instructors, citizens — set up these binaries, we are always-already limiting ourselves and what can be included in our discourse. I think this is where my writing mimics or mirrors my pedagogical approaches at the City University of New York and Pace University, where I’ve taught for the past six years. I would want to learn something new each time I facilitate my seminars, and I am very often the student in my classroom because I emphasize those dialogic interruptions — the ruptures you spoke of earlier — to create new connections or re-orient old ones, engender empathy, learn how to see the same thing quite differently. I am at a point in my writing where it is no longer enough to try and synthesize my different experiences and modalities into one text, I also need to match that accountability in my research and teaching. Yes, of course, the writing has to originate in pleasure, but I do believe that it should also be attached to a human project, a social project.

When we talk about traditional — or non-traditional — forms of writing, I do think we need to be careful about even imposing limits on what can or can’t be communicated at any given time. Jameson, like Adorno, said that what drives modernism is not some vision of the future or the new, but the belief that certain forms and techniques can no longer be used and should be creatively avoided. It’s the dead-end of creativity to believe that there are things already at our disposal that are off-limits. Benjamin could see the second-coming of the newspaper as a crowd-sourced, collaborative personal text half a century before social media realized that vision, and I think one of the reasons why innovation takes so long is the failure to re-orient our perspectives on what is commonly thought to be vulgar, or simple, or beneath art. I think that’s also the reason why I am so interested in relentlessly writing pop culture into literary and critical work.

Does this interest in challenging genre boundaries — and their implicit politics — inform your work as an editor and curator? Similarly, has your work as a gatekeeper challenged your thinking about hybridity? How so?

It’s been an immense and fruitful task to serve as an editor for three very different publications, and I continue to feel indebted for receiving that responsibility. At PANK, especially, I believe I was brought on board specifically to help find more hybrid voices/hybrid forms and to continue trying to dismantle outdated ideas that are unfortunately still so prevalent among literary journals and magazines — even celebrated ones, about what’s “literary” and what’s permitted, and who’s permitted to speak, and when.

When I was introduced as editor, I wrote a short essay about dismantling reductive ideas about left vs. right in terms of literature and thinking instead about turning forward as a direction that includes, yes, without a doubt political resistance, but not literature as political propaganda. And being raised by two parents who escaped oppressive regimes which were each, in their own way, prohibiting ways of thinking and living in favor of a government consensus, I am still sensitive to that approach to writing, but especially to managing a literary magazine. I don’t think consensus is a good thing; I do think true diversity in literature will only exist if there are diverse, intersecting views and interests between editors of different backgrounds and cultures working on a singular project. And in that way, my interest in hybridity matches my ideas or aspirations about an art and a text that are intersectional, irregular, non-normative, inclusive.

What are you currently working on? What can readers look forward to?

I’m so excited — and very fortunate — to be working on that critical/creative hybrid project focused on marginalized communities, immigration, and personal texts at CUNY’s Grad Center, where I am conducting my research under some really amazing thinkers and writers in the English department. I am indebted, especially, to Wayne Koestenbaum, as well as to my classmates, and the MAGNET cohort, for helping to shape my ideas on hybridity and moreover, for challenging me to re-create my critical research in a creative way. Recent pieces have included a close reading of Rebel Without A Cause against the backdrop of Eric Garner, Abner Louima, police brutality, and Google analytics; a selection of Brecht and Benjamin’s conversations, directions for dubbing dialogue in studio, an analysis of our culture of shaming, and excerpts from The Real Housewives of New York; and just this week, a text that combines cultural dislocation and the devastation of war with the decline of avant-garde art and the movie Death Becomes Her.

I have already had good luck in publishing excerpts from my own notebook, as well as generous assistances for presenting and performing excerpts from the hybrid research project at future conferences, like the Anti-Conference Conference, scheduled for December 1 and 2 at Johns Hopkins. On the full-length front, Death of Art’s non-fiction follow-up will be released by C&R Press next fall (2018) a sprawling, self-indulgent — even by my standards — hybrid book titled The Internet is for Real, which was originally organized as two volumes (birth & control) and then assembled into one, flipped upside down at the halfway point. This winter, Portland-based King Shot Press is publishing my novel about serialized fashion and serial murder called Drift, which has been in post-production since 2007 — 2007! — and I’m looking forward to that experience of time-travel that reading one’s self always produces, times ten. It’s fun to think that all these different projects, formed at different points in time and with different aspirations and endeavors, will all be circulating at roughly the same moment. I have a tendency — as artists, I think we all do — to already be captivated, thrilled, giddy about the next project, and I do believe there are things I still cannot understand about the hybrid work I am producing, but I guess that’s also the point, or the whole. I am here to be taught.