I met Jordi Alonso at a writers’ conference in New York in the summer of 2013. At the time, he was working on a series of erotic poems inspired by the Greek poet Sappho that would become his first book, Honeyvoiced, published by XOXOX Press. Jordi studied literary translation and poetry at Kenyon College, where he graduated with an AB in English with an emphasis in Creative Writing, in the spring of 2014. He went on to receive his MFA from SUNY Stony Brook, where he was the Turner Fellow in Poetry, and today he is a PhD candidate and a Gus T. Ridgel Fellow at the University of Missouri.

Jordi’s latest work, published by Red Flag Poetry, is a chapbook of 27 poems, accompanied by original illustrations by Phoebe Carter, whom he met at Kenyon. This gorgeous collection explores the complexities of language as each poem highlights an untranslatable word, and is brought to life by Phoebe’s artwork. You can order The Lovers’ Phrasebook here.

LAUREN KESSLER: Congratulations to you and Phoebe on your collaborative chapbook, The Lovers’ Phrasebook. How would you describe this collection?

JORDI ALONSO: It’s a creative exploration of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis [of linguistic relativity], how our native language shapes our behavior and ways of thinking. Languages are very indicative of culture. For example, sobremesa is a Spanish word that means “a conversation that lingers at the table after a meal,” which we don’t have a direct translation of in English. Even though we might do it once in a while, it’s still not a concept that exists in our consciousness because it’s not culturally important enough to be assigned a name. Americans spend only about an hour a day eating, while in other countries, particularly Spain, people eat for three. So, if something is not ingrained in our culture we do not have a word for it — we don’t need one.

One of the most appealing and unique things about The Lovers’ Phrasebook is its visual component: every poem is paired with one of Phoebe’s illustrations, and it will be published not just as chapbook, but as a book of postcards as well. How did this project start?

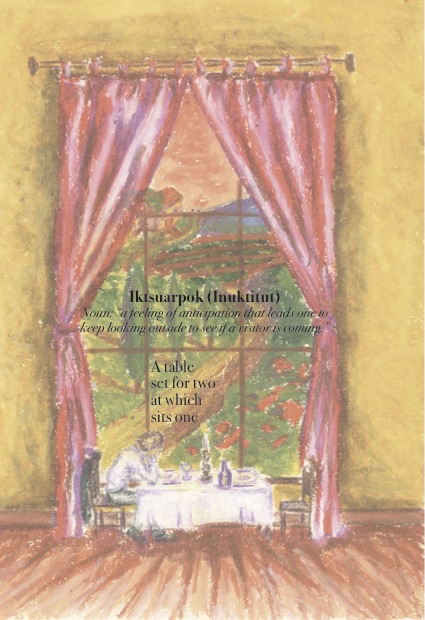

In the summer of 2014, after I graduated from Kenyon, Phoebe told me she was going to be an RA in the fall. The RAs at Kenyon decorate their hall with themes, and her theme that semester was untranslatable words. She had a list of about 20, with their definitions, and sent it to me because she knew I was obsessed with languages. From this list of untranslatable words, I took one at random: iktsuarpok, which in Inuktitut means “a feeling of anticipation that leads one to keep looking outside to see if a visitor is coming,” and wrote this poem: “A table / set for two / at which / sits one”

We continued adding words to the list until we ended up with so many that there was one for each letter of the alphabet, and when I wrote “The Dream of an Uncommon Language” I started envisioning this as a series. Meanwhile, Phoebe had been illustrating some of my poems as door decorations. Eventually I asked if she would illustrate all of them.

What does it mean for words to be untranslatable?

They don’t have a direct correspondence between the foreign language and English. Most of the time, that means you need almost an entire sentence to convey what would be understood with just one word in the source language.

What was your intention in writing about untranslatable words?

Exploring gray areas that aren’t gray in their native languages. By poetically defining the words, my hope is that they will enter our consciousness as human speakers so that we will stay at the table for longer than necessary (sobremesa, Spanish), we’ll run our fingers through a lover’s hair (cafuné, Brazilian Portuguese), we’ll have too many books to read (tsundoku, Japanese), and so on.

All 27 poems possess an honest, intimate quality. As a reader I felt especially engaged, because of the fact that the speaker addresses the lover in second person. While writing, what kind of speaker were you envisioning?

The speaker of the poems is an idealized version of myself…but at the same time, I didn’t want to do what Roger Rosenblatt calls “literary masturbation.” My hope is that when readers pick up this book they’ll be able to imagine themselves and their lover in the places of the speaker and his/her lover while inhabiting the language. I never explicitly gender the speaker. I’d hope for them to fill up the characters with themselves and those in their own life — real or imagined. It’s why I use the second person so much. I find that “you” is very easy. If you the reader see the pronoun “you,” then it’s possible to extrapolate from that and insert your own preferred identity.

Language is central to all your poetry, which isn’t surprising given your bilingual upbringing and education in literary translation. What is your relationship to language, and how does it play into your work?

I feel that most of my life has been spent in translation somehow, since I learned English and Spanish at the same time as a baby. My family and I speak Spanish at home, but I learned to read in English the first time I lived in the States. I studied French for 12 years in grade school and have since become fluent. At Kenyon I studied Spanish literary translation, Latin, and Greek. Those three languages and the interplay between them led me to write Honeyvoiced. Currently, I’m learning Catalan and modern Greek (as if getting a PhD in English at 25 weren’t hard enough!).

Honeyvoiced is a collection of poems inspired by Sappho’s fragments. Similar to what you did in The Lovers’ Phrasebook, every poem centers around a foreign word and its translation (in this case, in ancient Greek).

I call it literary archeology, a little bone fragment with which you build an entire dinosaur. I had a kernel of Sappho, maybe one or two words, and translated those to English, then built a poem around them.

Are there other parallels between Honeyvoiced and The Lovers’ Phrasebook?

There’s a callback, if you will. Phoebe was instrumental in the creation of the phrasebook, not just visually but also because she found some of the words. She suggested the “D” word, dhvani, because she said its definition reminded her of “Fragment 88,” from Honeyvoiced. Dhvani is Sanskrit and means “the artistic enjoyment from literary works achieved not by the images that are created by the direct meaning of the words but by the associations and ideas that are evoked by these images.” So, there’s this nebulous association of artistic influences.

For “Parea,” the painting hanging above the lovers is an illustration of Phoebe’s favorite fragment.

Could you tell us about your upcoming projects?

I’m currently editing a larger manuscript of poems focusing on desire in all its forms (from the domestic to the culinary to the sexual) that I’m calling Epicurerotica and a chapbook of erasure poems crafted from interviews that Björk has done in the last decade. At the moment, I’m planning a collaborative book of poems with Mara Vulgamore, a wonderful poet, visual artist, and dancer, who, thanks to the limitations of the English language and its lack of words describing relationships, I’ll call my best friend –– though that doesn’t do her justice. The Lovers’ Phrasebook is dedicated to her in the hope that its readers will be as enriched by the poems between its covers as I am by her love and her presence every day.

Phoebe, your illustrations really bring the poems to life and make reading them a special experience. Can you talk about your creative process in The Lovers’ Phrasebook? Were some poems easier to illustrate than others?

PHOEBE CARTER: Jordi’s poems are in themselves almost like verbal snapshots, so most of the images I drew came to mind during one of my first few reads of each poem. There were some that were trickier though: I remember spending a while on “Razliubit” (to fall out of love) trying to figure out how I wanted to capture that one, since it deals with emotion in a more abstract way.

What was it like to collaborate with Jordi?

Fun, inspiring, wonderful…I could just go on gushing adjectives. But really it was a great experience. We share a lot of similar interests and artistic concerns, namely words and multilingualism and how we communicate, so it was exciting to be able to explore these ideas through this project.

We were never in the same place at the same time while we were working on the book, so we did a lot of texting and Skyping as I was working on the illustrations. It was definitely a collaborative effort, since he gave me lots of input throughout the process. Especially when I was stuck on an illustration, it was nice to be able to call him up and bounce ideas around with him. I’m already looking forward to our next collaboration!

Both of you share a love of language. What attracts you to untranslatable words and how did your interest in untranslatable words start?

I study foreign languages and literary translation, so I spend a lot of my time thinking about words and how we express things in different languages. I think it is fascinating how our words and grammar attune us to different things depending on what language we speak. And you can have a word that is so central to speakers’ vocabulary in one language that doesn’t exist at all in another, but monolingual speakers of that second language will never feel that this word is missing (unless perhaps they come across it in The Lovers’ Phrasebook and then they start thinking, “darn, why don’t I have a word for ‘to have too many books to read?’”).

I first came across the idea of untranslatable words a couple of summers ago when I was cooking with my friend Malcolm (to whom my illustrations in the book are dedicated) and he started telling me about different words he’d learned. One of the first ones he told me was a Georgian word, shemomechama, that means “I accidentally ate the whole thing” and is used when you start nibbling away at something without meaning to eat very much and then you end up finishing it. Not that I’ve ever done that…Anyway, I told Jordi about it and we started collecting words from different people and corners of the internet. And here we are today.

What do you think would happen if the whole planet spoke the same language?

What a good question. It would be a real loss to the diversity of this planet. It would be the loss of the histories and worldviews and literature that are encapsulated by each language. The first poem in the book, “The Dream of an Uncommon Language,” centers around this question. Jordi writes, “I will not dream / of describing my love / if not in every language,” and I think the whole poem is getting at the richness of expression that is available to us because of the different ways in which each language constructs the world.

Unfortunately, we are moving toward a linguistically anemic planet; another language falls out of use every two weeks or so and it is predicted that about half of the languages spoken today will have disappeared by the end of the century. Of course, in our increasingly globalized world, it is both necessary and wonderful to be able to communicate with people on the other side of the planet. But it is important to be conscious of on whose terms we are communicating, and what we are losing in translation. I hope that The Lovers’ Phrasebook gets people thinking about these things.

Also, I would need to find a new career path.