Translation begs for metaphors. Translation is a pineapple, a symbol of hospitality, at once fragrant and spiny. There’s something daunting and extra-sacred about the act, especially to those of us who aren’t practitioners. The translator may be polylingual, a syntactical contortionist, a whiz with other writers’ words. Translating suggests summoning, conjuring, dictionary-wading, and thesaurus-spelunking, peering at the page closer than the most fervent fans — all on that quest for the pineapple. Welcome to the home of this writer, the translator says, playing perfect host. Allow me to make festal this acquaintance.

I was introduced to Austrian poet Friederike Mayröcker only recently, but my host, writer Jonathan Larson, has been so gracious that I feel as though I’ve been reading Mayröcker for years. Or perhaps what I feel is that I might be about to be reading her for years. That is not hyperbole. Mayröcker is the author of dozens of volumes. She’s written books of poetry and plays, radio plays and children’s texts. Her voice is magnetic, effusive, and open; her language efflorescent and echoic. Her use of abbreviations and archaisms bend what seems possible in a single poem. Her writing, as translated by Larson, is a pineapple you’ll want to devour, spikes and leaves and all.

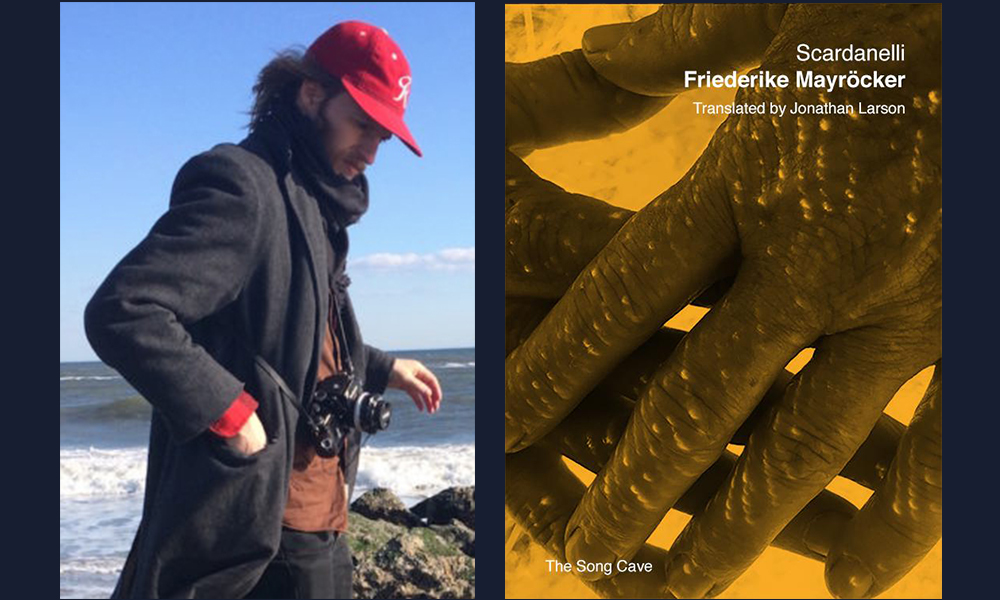

Jonathan Larson is a poet and translator living in Brooklyn. His translations of Friederike Mayröcker’s Scardanelli and Francis Ponge’s Nioque of the Early-Spring were published by The Song Cave. OOMPH! Press will be publishing his translation of Mayröcker’s from Embracing the Sparrow-wall, or 1 Schumann-madness.

Larson and I discussed dictionaries, in-betweenness, philosophies of translation, poetics, and more by email in the middle of February 2019.

¤

JOANNA NOVAK: Scardanelli, your second book of translation, was my introduction to Friederike Mayröcker, a literary tour de force (author of more than 100 volumes!), whose poetry, in your translation, is frank, efflorescent, violent, lush, and utterly magnetizing. What was your introduction to Mayröcker? How did you come to translate Scardanelli?

JONATHAN LARSON: I’m both moved and honored to have played a part in the transmission process. Mayröcker’s writing bubbles up, cuts and jags, then shimmers all at once and so much so that it’s next to impossible not to get caught up in the trance when speaking to it, or translating it, for that matter. Almost ten years ago a good friend of mine moved to Vienna to study architecture and sent me a copy of Ernst Jandl’s Laut und Luise — Jandl, an integral figure within the “concrete poetry” group, was Mayröcker’s longtime companion until he died 2000 — which then led me to stumble across Friederike Mayröcker’s 2003 Die kommunizierenden Gefäße (The communicating vessels) in a Half Price Books in Seattle. Reading it was to be swept up in the rush of language by the first phrase, a tactile, textual immergence, a new way of seeing, of reading. The work itself is an incantatory patchwork of dreams and memories, many of them interspersed by delightful pen drawings, propelled by desperation and loss, primarily that of Jandl.

I was just starting to experiment with translation at that time, some Kafka and Mallarmé, and gave the book a try, mostly as a means of continuing to read it. At first it felt like brushing up against the impossible — could “1,” which in German could be read as both the article and the number, adjective and noun, as it is in Spanish, work the same way? As in, could an English language reader read “1” as “a” or “an”? But I mostly just kept playing at it, and eventually moved on translating two prose-poem collections, “études” and “fleurs.” Somewhere in between working on these, I picked up Mayröcker’s 2009 collection of poems Scardanelli, drawn to its mystic evocations of Hölderlin and how, throughout the book, starting off with forms more conventionally identified as lyric, it accelerates toward an expanded/expounded/exploded lyric that, by the last page, abuts the “tender prose” of the books that came after — a muscular, lean, tightly woven paratactic phrasing.

Introducing Scardanelli, you describe Mayröcker’s much-documented one-room flat, which ones imagines as sort of a Bohemian version of a Marie Kondo nightmare. Mayröcker, you write, is “staging a living performance of writing.” What would the living performance of translating look like?

That’s such a lovely way to put it! I suppose there would be as many modes of translation as there are modes of writing, and that they would reflect each other in some way. But in the case of translating poetic writing, and in particular texts by writers that reject closure (in the Hejinian sense), it might involve opening oneself up to the poem, but not just the poem-as-itself, but also the spaces and cluttering around the page, its tonic vibrations, the arrangements of phrase. I just finished editing a Mayröcker translation that culls material from the letters of Robert and Clara Schumann and “rebiographs” them onto a contemporary piano performance in Vienna, so I’ve been kind of wrapped up in the echoes of that performance. There’s the music that passes through the body of the pianist giving a concert at the café, and its momentum and bodily production transmute the texture of that room, and this comes out in the writing, in descriptions that “summon circumstances into the transience of our awareness of them” (from Hejinian’s Positions of the Sun). Incidentally that event also takes place in Mayröcker’s apartment in the Zentagasse, in Vienna, with its own ambient life. So, when we’re translating we’re hearing the performance of that room (in the text), passing through Mayröcker’s room inside our room, at our desk, in our chair, with our clutter, but making sure that both rooms (and of course the café) come through in the translation. In a sense, it’s a tale of two rooms, the one set inside the other without “localizing” it.

What draws you to translation? Where does that work intersect with your own poetry?

I spent some of my childhood years growing up in Germany and so I learned German and then French at an early age. Those experiences introduced my first estrangement from and toward language and how words derived their magic function from the social context within which they were used. Much has been made of all the various etymological undercurrents of the word “translation” and most contain shades of “drawing across” or “traversal.” I gravitate toward this in-betweenness, of longing for and seeking out a juncture, or a disjuncture. I’m fond of what Paul Celan once said in a letter, the he could see essentially no difference between a handshake and a poem.

Part of what makes reading Scardanelli such a delight is what you describe as “Mayröcker’s resistance to typographical standardization in favor of a pliable language.” That resistance leads to abbreviations, the inclusions of numerals, surprising shorthand and archaisms, but also jaunts in capitalization, punctuational polygamy, elisions, etc. What special challenges or challenging joys did that “pliable language” pose for you as a translator? What effect did you want to impart to the reader?

I’d say they start as challenges, and kind of stick around as challenges, but the good kind. These conventions (or contraventions) are part and parcel of the reading experience. Because of the typewriter Mayröcker has used exclusively since the 1960s — the Hermes Baby, a Swiss make which came without the German “ß” letter — her texts instead replace it with “sz.” I tend to think that Mayröcker’s deployed short-forms anticipate writing within digital media, the feeling of always being pressed for the time and space to text the message out, cutting, chopping, contracting. I can’t remember the first time I came across “wrt” in a text but many of us will automatically think/say “with regard to,” even if it threw us off the first we encountered it. My hope is that when the reader enters the translation, what might first read as a skipping record, eventually becomes an ambient feature of the track.

Mayröcker’s sensibility shifts so wildly within a single poem, which often seems to be composed of single-stanza verses written in a compressed period of time. “the canvases maybells 2008,” for instance, begins:

songs of madness the old stone pine-limb broken, breathing

the edge of the woods the pain and squeezes its blood from these

sweet veins, I begged for loneliness security soc-

ial grace, Updike, and there in the corner the

black men’s umbrella. Full-bosomed at 15 in front of the big

mirror …

And in the next verse, the speaker is imploring: “be with me in my language craze you have/pressed the floral wreathlet into my hair since I 1/child.” Later: “we fled hand in hand/through forests bushes rose gardens oh such ecstasies.” Pastoral, confessional, Romantic, your translation is so carefully modulated. How do you think about tone and mood when translating?

I imagine it’s about trying to get a feel for the constellations of sound and sense, to follow the range and timbre, the vibrations of the voice. Maybe improvisation could be an apt analogue here, how, once you’ve picked up on the key that someone else is playing in, and you know your scales, you’re able to pick up on a groove and play along. But just playing along would make for a boring and redundant translation, and, as you say, the thrill of Mayröcker derives from this writing on the edge, always probing the outer limits of each phrasing, so it’s also a matter of pushing toward that edge in the translation. Besides following the pitch of the poem, reading and rendering mood calls for inviting a panoply of choruses into the process. I studied translation with Ammiel Alcalay who was very instructive as far as striving for a maximalist register, widely consulting other translations and writers across the spectrum of the English languages to grow one’s repertoire of translational models to draw on.

In your introduction to Nioque, you observe “the artist is reintroduced as the capacity to remake and remark upon the past in advance of its future.” I like how this positions the past as belonging to the future, as well as how the artist’s work with the past parallels, perhaps, the translator’s work with an artist’s text.

To me Nioque is in so many ways about taking account of what’s really there. There are all these Lucretian undertones throughout, about the natural world comprised of all the particular atomic seeds that come together to form new agglomerations of concentrated mass, new order, only to inevitably wither away and breakdown and put toward some other assemblage — Whitman’s “uncut hair of graves.” And Lucretius, as Ponge, sees language undergoing the same transformations that we observe in the “natural world” when we change around the order of a sentence, or translate it, even, that there’s a certain number of combinations out there recombining and melding, which we are a part of and participate in. The utopian imagination also has a part to play in translation, producing a new dream image from what was there before.

Ponge’s parentheticals quickly proliferate in the prose and poems that constitute Nioque; a reader learns that those parentheticals approximate a murmur, a stammer, a doubling-back on one’s expression — but sometimes more. As a translator, how do you approach sartorial punctuation?

I guess it has something to do with feeling one’s way along — à tâtons in French — as one gropes one’s way on, by touch, tact, or taste, all leading back to the Latin tango. Ponge so admirably shows us how he’s getting clear of what he’s saying in saying it, an approach we can follow along in Mayröcker’s syntax, too. In both cases, though, their choices become part of a rhetorical mode articulating both the potentialities and limitations of their languages, so what can or can’t come across in its use is also at stake. As an example, Mayröcker will often leave out the verb that comes at the end of the phrase in German, the missing action piece to the concluded meaning, which nonetheless has already been anticipated beforehand from the logic of the other parts of speech. Because we have no tense in English that pitches the verb to the end of phrase, I’m always looking for other ways of disguising its absence, juggling around the word order to achieve a similar striking effect that feels consistent with — or rather, diverging just enough from — English sentence structures.

Hölderlin is obviously central to Mayröcker’s work in Scardanelli, but you allude to him in your introduction to Nioque. How does he figure in your own poetics?

I see Hölderlin as a utopian visionary who wrote poems as androgynous palimpsests of sound, sense, myth, and history. There’s a compacted extensiveness that warps time and space in his poems that I really admire, something that still speaks in startling new ways to our contemporary sensibility. It’s also important to me that Hölderlin never “grew up.”

What are you working on now?

I’m really excited about a shorter Mayröcker prose text titled from Embracing the Sparrow-wall: or, 1 Schumann-madness that OOMPH! Press will be publishing in the next several months. I’ve also been translating Mayröcker’s latest collection Pathos and Swallow, along with some scattered Francis Ponge texts — one in particular titled As for Flowers that moves me. And I’ve been slowly working on translating the poet Joë Bousquet — the Novalis of the Mediterranean — a wonderful early 20th century meditative writer who hasn’t yet appeared in English. When I’m not working on those projects I’ve been spending time with my own poems.

I often hear readers worry about analyzing stylistics choices, such as diction, when reading translation; there seems to be a fear that, since one is not reading the text in the original, one might be missing out on … something. How might you assuage such concerns? What practices or philosophies guide your translating?

I see that sentiment a lot, too, and my sense is that a lot of people approach translations with suspicion due to an ingrained belief in the hegemony of “the original” — especially if the reader has no access to the language of the translated text. Your linking reading translations to FOMO is really incisive to me. I think it might not only have something to do with the hyperabundance of books being deliciously consumed up and down our feeds, but this conviction that we can and should either buy out the entire network of associations once we’ve cracked the spine of a book or not page through it at all. It seems to be just another symptom of late capitalist reading habits by which products that aren’t going to provide a “seamless experience” are mistrusted. I would argue that there’s also a misunderstanding of literary works in general here, in assuming that an original work is composed of “pure language.” While of course, there are bad translations, like Milan Kundera’s French translator who stronghandedly cleaned up his purposeful “bad writing,” but I think that’s a separate issue, since those are by and large minor incidences. At the end of the day I think the antidote is to produce and consume more translations.