By Tom Stern

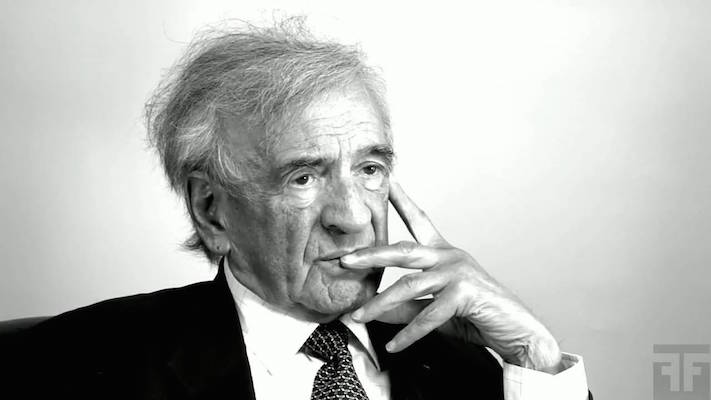

Dr. Elie Wiesel

New York, NY

July 23, 2016

Dear Dr. Wiesel,

I don’t know how to do this. And I’m embarrassed to admit that. Because I am a writer. This we shared. And in ways that I suspect very few people do. Like a constant fever. And a compass. Somehow both at once. Even so, I simply don’t know how to articulate what it was that you taught me.

To begin with, it was unexpected. I signed up for your class somehow without even thinking about you as a writer, what with this whole humanitarian/Nobel Laureate/conscience-of-the-world thing in the foreground. Frankly, I did not even expect that we would meet one-on-one throughout the course. I was surprised when we did, and even more surprised when we started to talk about writing. And I was speechless when you asked to read my work, and a neurotic mess for the following week until we met again. Not that you treated me as a novice, quite the contrary. I remember we talked about my work and about writing for a half-hour. But I only recall one thing that you said during that conversation. And I still don’t understand exactly why this thing has literally shaped every single day I’ve lived ever since. But it did.

It was well into our conversation. You cast your stare off a moment, as if you were questioning whether or not to convey the thought that had surfaced in your mind, considering its weight and context and consequence. But eventually you nodded slightly and shifted your gaze back to me and said, “If you really take yourself seriously as a writer, you will make the time and you will sit down and you will write every single day.” You punctuated these last three words as though each was its very own sentence. Every. Single. Day. You said it did not matter if I wrote for 20 minutes and pure drivel came out or if it was six hours of unbridled inspiration or anything in between, that if I really considered myself a writer, I would write.

Now, I concede that many people might not consider this a massive philosophical concept that pries back the layers of perception to expose the burning light of truth itself. But for me, that is exactly what your words did, in that moment and well beyond.

And this is where language and intellect start to fail me.

So here is what I know:

- I left your office that day and I sat down and I wrote.

- And then I wrote the next day, too.

- And the next one.

- And every single day thereafter right up until today, some 18 years later.

- I write when I’m sick and when I’m well. When I am inspired and otherwise. I write when I feel like writing and when I don’t. I write when I’m working on a larger project and when I’m just pushing words aimlessly around a page. I wrote on my wedding day. I wrote in the hospital on the day my daughter was born. Even when I can only find my way to a few hours of sleep in a night, I still wake up not long after dawn and I write.

- I truly believe that a monster would take over my soul and body if I did not find time to write each and every day.

- I just wrote the following text to my wife regarding this letter: “Just don’t know how to make sense of it all, how to articulate something so foundational to whom I’ve become. I still don’t understand what happened and has happened thereafter. Don’t know how to say such things.”

Writing is my foundation. On good days, it orders the unrelenting cacophonous stream of phenomena that is life. On bad days, still it at least paints some faint path forward. But without it, there is no sense. There is no direction. There is no understanding. And there certainly is no way to bridge one person’s human experience to another’s, let alone to extract some sort of moral or ethical or philosophical framework within which to live. I understand this about myself now. But only fairly recently. Because this is the type of understanding that one can only really attain after nearly two decades of writing. Every. Single. Day. So this I have learned from you.

Which brings me to just some of the questions I still have for you:

- Did you know that your words would have such an impact upon me?

- Did you hope that your words would have such an impact upon me?

- Did you know that the knowledge you were sharing was the kind that broadens, expands, refines, grows, alters as the prism of time continues to add context all around it?

- Was any of this even what you were really trying to say to me or have I projected my own neuroses and skepticism about the potential meaninglessness of life upon a simple conversation that I desperately wanted to be significant?

- Do you think a monster would have overtaken your soul and body if you had not written for even just one day?

- Did writing really mean this much to you, too? I like to imagine it did.

- Do you miss it? Or do you get to somehow take it with you? I want to believe, with all of my heart, that somehow you do.

I have resigned myself to the understanding that my questions for you on this topic will never end. But I take solace in another lesson I remember you sharing, this one during one of our class discussions. You said that sometimes simply asking the questions is abundantly more meaningful than having answers. Sometimes all that a person can do is really, truly, deeply ask a question with everything in his or her being. And just keep right on asking it, keep right on seeking. Every. Single. Day.

That said, here are just some of the truths about what you have taught me that seem to have come into focus over years and years of questioning:

- Writing is an action, not an accomplishment. You and me, we are writers. And sometimes as writers, you go on this odd carnival ride of being an author — yours far more elaborate than mine, I’m sure. But this is not about that. Not for us. We are writers. We write.

- The action of writing allows one access to the most human parts of being alive, limited only by how hard you are willing to look and how deeply you are willing to ask questions.

- Being a writer is how people like us learn to be in the world. If we are wise, we will approach all facets of our life with the same singular focus, critical openness, and unyielding drive to articulate and understand.

- If you want to say you are something, all you have to do is truly be that thing.

- If you want to truly be something, it might take a very long time and a lot of effort to become that thing.

- It might even be the hardest thing in the world to truly become that thing.

- Just because you say you are something, that does not truly make you that thing.

- Truly being something is never the same as what you think truly being that thing will be.

- Writing is writing. It takes place 99.9% of the time when no one is looking.

- As writers, the overwhelming majority of our time is spent failing. In fact, pretty much all of our time is spent failing. But this is where the actual meaning and the value lies.

- Who you are is more important than being a writer. But being a writer is your most powerful tool to understanding who you are.

- Today is the unit of currency of our actions. What we do right now, today, is all that we do. Everything else is hypothetical or historical, which can and does have an impact upon today, but today is where we do.

- If we ask the right questions, if we really work to ask them, we just might find a meaningful path forward through life.

- All paths forward will require reinvention when old questions turn into new ones.

I could keep going.

I could unendingly add to all of the lists above and I still would not have said enough. I carry this like a failure. I carry this like an ever-deepening question. I realize that this is all there is for me. This is a writer’s life. This is my joy. And I fail here in your honor, hopefully closer to inspiration than drivel, but I have learned over the years that such things are not for me to say. So I thank you for this lesson, too. It is the only thing that gives me the abandon to write this to you now.

I am truly humbled and honored to have learned from you. May there be words and thoughts and paper and pen for both of us wherever things go from here.

Your Student,

Tom Stern