An autumn afternoon on the sunny Great Lawn at Westlake School for Girls. Lorraine Schulmeister, English teacher, and I read aloud from Emily Dickinson: I dared not meet the Daffodils — For fear their Yellow Gown Would pierce me with a fashion So foreign to my own –; we read aloud from Blake: If I worship one thing more than another it shall be the/ spread of my own body, or any part of it.. It’s 1967. I’m in the tenth grade, my first year as a scholarship student at this exclusive school tucked into Beverly Glen canyon north of Sunset Blvd. It sounds idyllic – it was.

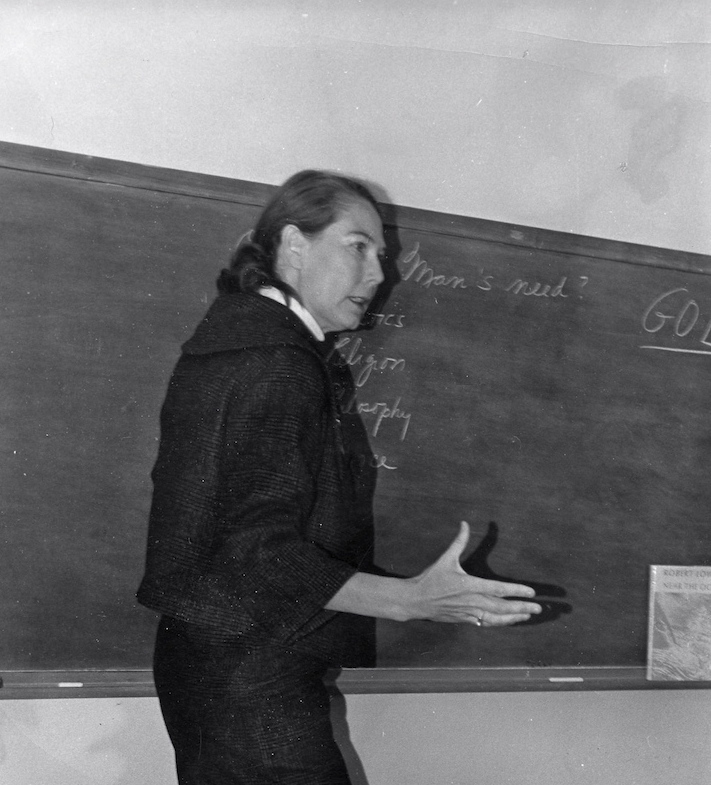

I picture her pacing in front of the blackboard: high Nordic cheekbones flushed, excited hands mid-gesture. Like the poet Theodore Roethke, her own mentor, she had mastered the art of appearing to see the work for the first time. She introduced us to the poetry of Muriel Rukeyser, Ted Berrigan, Robert Lowell, Denise Levertov – to the possibilities of writer-as-activist. It was a stance with immediate resonance as the Vietnam War raged abroad and protests raged at home.

After school, I’d trade pastel shirtwaist uniform for torn blue jeans and sandals and hike down to the Resistance office in Westwood Village to pick up leaflets to hand out at draft boards. My high school boyfriend, almost 18, refused to register. Instead, he chained himself to the altar of a church in Watts. U.S. Marshals obligingly hauled him away to court, from there to federal prison.

Lorraine taught at Marlborough School (our cross-town rival) before teaching at Westlake, but resigned when the administration there questioned her “Americanism.” There’d been complaints from parents: when she taught Whitman, she actually spoke about “sex” in the classroom.

In her eloquent resignation letter, dated February 29, 1964, she wrote: “I have presented American Literature as a great and living force, as a body of work that is loving and critical at one and the same time. Like Frost, most writers have had a ’lover’s quarrel with the world.’ Literature is most of all concerned with life; sex is an important part of life. I presented Walt Whitman as I have always presented him: as poet of the body as of the soul; as the great revolutionary and innovator that he was.”

She was born Lorraine Breckheimer in 1918, in Mankato, Minnesota. It was the year the Great War ended, as she noted in The Making of a Teacher or The Last of the School Ma’ams, her astute self-published chapbook. Mankato was a small town “far from the currents of the world.” No movie theaters. No television. A quiet, peaceful life—walks, berry-picking, window-shopping, band concerts, school plays, church. A trip to the library was an adventure. “No one we knew had had a divorce. Only teachers traveled to far off places.”

In the crash of 1929, her family fell “from the middle class to no class.” Her father’s farm implement business failed, he lost everything. The family moved to a dairy farm in northern Minnesota classified as “suitable only for subsistence living.” Living in this rural isolation, from age 11 to 17, Lorraine turned inward, books were her companions.

She received a full scholarship to Carleton College, but had no money for room and board. Disappointed, she opted for a state teachers college closer to home. An advisor discouraged her from seeking a PhD to teach at the college level. He told her she’d just be asked to teach remedial courses, not literature. “I recognize the truth of Karl Marx’s economic interpretation of history,” she wrote. “Economics has ruled my life.”

Her career included a stint teaching elementary school in a rural two-room school, where she was successful, for the most part, in awakening her students to the importance of reading and the pleasure of literary study. “Only one parent objected to my reading list. The offensive book was Steinbeck’s Cannery Row”. During World War II she served as a WAC at an air base in Ogden, Utah, and, courtesy of the GI Bill, studied American Literature at the University of Washington with Theodore Roethke.

Lorraine and I re-discovered each other in 2001 and remained fast friends until she died this past spring, at age 94. At least twice a year, I’d drive up to San Luis Obispo from L.A. We’d go out for dinner, a glass or two of good wine. She always brought a list of things to discuss; wanting to make good use of our precious time together.

Her home for the last decades was a small studio apartment in an assisted living facility. A painful and economically disastrous divorce (she kept his surname, Schulmeister, which described her chosen profession) in her early fifties severed her from her teaching career. She’d wanted but had no children, though a number of former students stayed in close touch. We were, she said, “the daughters she never had.” She worried about outliving her modest savings, and she almost did.

We stayed in touch by writing letters. Envelopes in Lorraine’s clear cursive arrived at least twice a month, and I wrote back almost as often. We sent each other books. Who else would gift me Henri Troyat’s massive biography of Tolstoy for my birthday? (As good as she said it was, all 800 pages.) She insisted I read President Obama’s memoir; she admired him, worried about him. She loved Hazel Rowley’s bio of Sartre and De Beauvoir and marveled at Yiyun Li’s short stories. Her responses to Manning Marable’s biography of Malcolm X, Susan Jacoby’s An Age of Unreason, Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland (she read it twice) fill pages handwritten front and back. She re-read the classics — Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Her unequivocal vote for greatest American novel was Moby Dick (she loved it more after each of her eight readings).

Of all the books I sent, her favorite was Adam Hochschild’s To End All Wars. She considered his skillful narrative of those advocating for peace amidst the carnage of World War I to be one of the most significant history books ever written.

I wrote to her about my own writing life, my own struggles and joys. She reminded me of my great good fortune to live in a creative community, to meet great writers, to travel, to observe. She adored my husband.

Among the many books I treasured receiving from Lorraine was Robert D. Richardson’s study of Emerson and the creative process (First We Read, Then We Write). Last year I made a pilgrimage to Concord, Mass to swam in Walden Pond, place pencils on Thoreau’s grave in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, and visit Emerson’s home. I sent Lorraine a postcard– an image of Emerson’s study– featuring the round oak table where the master read and wrote every day. Emerson’s belief that creative reading was essential to creative writing was one that Lorraine instilled in all her students. She concurred with Emerson’s dictum, “While you are reading, you are the book’s book.”

Reading kept her mind young even as her body failed her. Historian Tony Judt’s final book, Thinking the Twentieth Century, thrilled her and she zeroed in on his chapter about American nationalism. “In a global world,” she wrote me, “we are so provincial. Witness our current politics. We are anti-intellectual as a people. More so than others.”

This she found as true in 2012 as when she had resigned from Marlborough nearly fifty years earlier. She ended her resignation letter with a ringing admonition:

“Everyone should read President Kennedy’s speech at Harvard, dedicated to Robert Frost, published in the February issue of The Atlantic Monthly called ‘Power and Poetry.’ He expresses better than I the challenge America faces: Can we have poetry and power? Athens did for a brief moment in history. It seems unfair that I should have been asked to remain at home so that a student could attend class without contamination from an accused teacher; why should the teacher be more expendable than the student? I do not at this point know the real charge against me, but I do recognize the forces that are greater than myself. I represent poetry; they represent power.”

On the day Lorraine died, one of her former students, Judy Munzig, was able to spend several hours sitting at her bedside stroking her hand, telling her how much we all loved her. Lorraine’s eyes were closed, but she could still hear.

Judy wrote afterwards: “Her reading glasses were on her nightstand on top of a paperback of Iris Murdoch’s The Bell with a bookmark from Chaucer’s Bookstore. A young man who works at the hospice said that Lorraine had been reading passages aloud to him and when he told her he didn’t understand it, she would explain it to him. ‘Now I’ll have to read it myself,’ he said.”