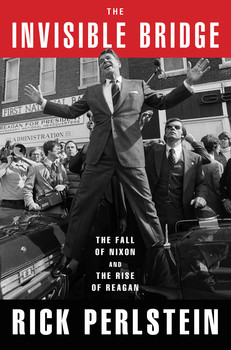

Today’s post, a review of Rick Perlstein’s The Invisible Bridge, was originally published by LARB Channel Boom.

By Thad Kousser

When the immigrant refugees were first transported, in huddled mass after huddled mass, into federal facilities spread across the country, local reactions were visceral and virulent. Residents signed petitions to let them know they weren’t welcome, talk radio fanned the flames, and a San Diego congressman reported that his constituents saw the ostensible refugees as nothing but “diseased job seekers.” While the president preached that “we can afford to be generous to refugees” as “a matter of principle,” Governor Jerry Brown urged that any bill passed by Congress to aid the immigrants should be amended with a “jobs for America first” pledge.

Wait, didn’t Brown just promise to do “whatever can be done by a mere governor” to aid the immigrants? Ah, yes, but that was his reaction to the current wave of Central American migration. His less charitable comments came in 1975, after the fall of Saigon led to the settlement of Vietnamese immigrants in relocation sites across a divided and uneasy nation. Rick Perlstein relates this story, along with many others that eerily echo California’s present and past politics, in his expansive, rich, and masterful The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan(Simon & Schuster, 2014). It is a portrait of these men but mostly of their times, an era that begins with the sins of one landmark Golden State politician and ends with salvation being promised by another. California is not the setting of Perlstein’s national drama, yet the state shaped both of its leading players, readying Reagan especially to play his role to perfection.

The Vietnamese refugee crisis was part of the moment that launched Ronald Reagan into national prominence, allowing him to save his party from its undoing by Nixon. On the radio show that he took over after leaving the governorship, he called for generosity and assistance for the immigrants, as always through skillful use of anecdote. Reagan retold the story of how the USS Midway, now a docked museum in San Diego Bay, came upon a sinking boat loaded with eighty-two refugees in the Gulf of Thailand. The mighty carrier maneuvered to rescue them, promised them safety, and even cured a baby with double pneumonia. The sailors fulfilled the vision, which Reagan was so fond of quoting, set forth by Pope Pius XII after the World War II: “America has a genius for great and unselfish deeds. Into the hands of America God has placed the destiny of an afflicted mankind.”

By simplifying a complex issue like the refugee crisis, which had set charity against economic necessity and pitted leaders from the same party against each other, Reagan gave his listeners moral clarity in muddled times. This—though it clearly pains Perlstein to accept simplicity as a political virtue rather than an intellectual vice—explains Reagan’s enduring appeal.

The echoes of this anecdote are easy to hear outside of Murrieta’s Border Patrol station and across California today, and they remind us of political constants. Many—though in the case of Jerry Brown, not all—of the names may have changed. The political positions that California’s leaders are permitted to take have changed, giving the latest incarnation of Governor Brown the chance to take a position today that we may imagine is more in keeping with his moral and theological views. But many of the most basic instincts of people, which become our most heartfelt and galvanizing political positions, remain the same.

Reagan always understood, in a way that Nixon never seemed to, how to connect with voters at an unrepentantly human level. How, asks Perlstein, could Reagan convince the GOP and the nation that it would ascend again after the disgrace of Watergate and the debacle of Vietnam had dragged the national psyche so far down? He had been perfectly prepared for the task of connecting with Americans through the haze of the 1970s by his political upbringing in California.

California’s story is the story of bust and boom again and again. A remote and dusty failure that could not attract more than a few thousand immigrants more than two hundred years after its European discovery, the state yielded gold and instantly became one of the world’s immigration magnets. After episodes of drought in Los Angeles, including one in the 1870s that left LA a parched wasteland littered with cattle corpses, the city’s brash engineers and real estate barons conspired to build an aqueduct with enough water to support its exponential growth. John Steinbeck’s impoverished farm workers of the Depression got jobs in WWII factories and then the booming aerospace industry. When that collapsed, Silicon Valley generated unfathomable wealth from its wares, hard and soft and now in the cloud.

Reagan knew the cycle, and his Hollywood background taught him how to tell the story in a way that would make America believe in it—and in him. Perlstein, a Chicagoan, does not give California explicit credit for Reagan’s success. His focus is instead on the way the actor’s amiable and simplistic reaction to frightening and complex realities served him so well.

Perlstein introduces this explanation of why Reagan was the right man for the times early on, when California’s governor dismissed the Watergate investigation as a “lynching” even as fellow Republican leaders began to grasp its gravity. His support for Nixon was full of contradictions and quips. Party operatives may have bugged the Democratic office, but “It seems to me that they should have been happy that somebody was willing to listen to them,” Reagan laughed. “Just this sort of performance of blitheness in the face of what others called chaos,” Perlstein writes, “was fundamental to who Ronald Reagan was. It was fundamental to why he made so many others feel so good. Which was fundamental to what he was to become, and the way he changed the world.”

And the world certainly produced enough chaos in this era, with California leading society’s apparent spiral downward. Perlstein reminds us that before Jimmy Carter’s stagflation, inflation was so severe that housewives organized boycotts against the skyrocketing price of meat while their husbands bemoaned a steep rise in the fees charged by prostitutes. When the Middle East sent its first oil shock, gas lines were longest in California. Crime rates were considerably higher in the 1970s than today, horrifying the state and nation, and taking victims from all stations of life. In Los Angeles, gang members shot down a mother of three and a maintenance worker who were guarding a church against vandalism. Up in Berkeley, Patty Hearst became merely the most famous of the many victims of kidnapping when the unknown, perplexing Symbionese Liberation Army broke into the sophomore’s apartment near the University of California campus.

When society seemed to go mad on a national scale in the 1970s, Reagan knew his lines; he had previewed his performance a decade earlier during California’s earlier flirtation with apocalypse. After the Watts riots and Berkeley sit-ins, his inimitable combination of stern words and avuncular manner convinced voters that he—not the two-term incumbent Pat Brown, now lionized as the man who built the modern Golden State—would be the governor who could save it from its wanton youth and a society breaking apart.

California politicians are naturally versed in the dialect of rise, ruin, and renaissance, and Reagan played his part well. Name your enemies: the Soviet Union, those who would impose socialism at home by supporting welfare queens, and President Ford with his near-traitorous policy of détente. Anoint heroes: the returned POWs from Vietnam whom Nixon cheered so loudly to distract Americans from his sins, along with all the members of the “silent majority” who did not trust what the East Coast media told them about America’s decline. This was still the greatest nation in the history of Earth, Reagan assured us. The dilemmas it faced were not complex but black and white. He knew, just as he had in California in 1966, the right answers.

From this self-assurance and Manichean framing was born the New Right. The last half of the book relates, in consistently fascinating detail, Reagan’s sharp move to the right after serving as a relatively centrist governor and his improbable challenge of President Ford. Reagan became a quick convert to the pro-life movement, which first flared in San Diego where the diocese refused Holy Communion to any Catholic who admitted support for abortion or membership in the National Organization for Women. As his national profile grew through radio broadcasts defending free enterprise and a more muscular foreign policy than Gerald Ford’s détente, Reagan dared to run against a sitting president in his own party, the Eleventh Commandment be damned.

There is but one slight flaw in Perlstein’s narrative of why Ronald Reagan was the perfect politician for the troubled post-Nixon years: in 1976, he failed. A third of the way through the primaries, Reagan led the delegate count by a 476 to 333 margin. When the GOP’s national convention opened in Kansas City, he had a legitimate shot at besting his own party’s sitting president. Yet, after picking a shockingly liberal and nearly unknown—even to Reagan himself—vice presidential running mate, he could not quite defeat Gerald Ford.

Ford would go on to lose to Jimmy Carter, and all signs indicated that Reagan would have fared even worse. Just after Carter’s triumphant speech at the Democratic Convention, a Harris poll had him beating Ford handily but leading Reagan by a massive 68 to 26 percent margin.

At the close of Perlstein’s book, Reagan has only the support of a minority within a minority party. But he has won their hearts by staking out bold positions less in keeping with his record as a moderate California governor and more in line with our state’s current political polarization (which a new Princeton study reminds us is the worst in the nation). After engineering the passage of a “pro-life, anti-détente, pro-gun, antibusing, pro-school-prayer platform,” Reagan proclaimed, “I believe the Republican Party has a platform that is a banner of bold, unmistakable colors with no pastel shades.” Ford may have won the battle at the end of that boisterous convention, but Reagan and his New Right allies would, four years later, win the war. How was he able to build his much longer bridge to victory, after the New Yorker declared, “This is probably the end of Reagan’s political career”? For that, we’ll have to wait for Perlstein’s sequel.