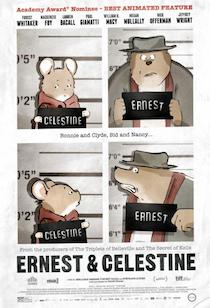

Photo: Ernest and Celestine, New Video Group, 2014

Today’s post was originally published by LARB Channel Marginalia.

We were both light in the head from a five-mile hike that had verged on a vision quest — too many miles with too little water under a cloudless sky at Calabasas Peak. It therefore took me a moment to adjust when we found ourselves later that evening strolling through rings of bunting-balloons, a grand promenade of red, white, and blue arches that slipped into the distance, suggesting a Homeric archery contest produced by Marvel.

“These balloons can’t possibly have lasted since the Fourth,” I said. Brad agreed. Pulling on a water bottle, I did some elementary arithmetic that should have been easier than it was.

“Dude, this is Bastille Eve.”

Brad consulted his phone. It was Sunday, 13 July.

The Community Services Department in Beverly Hills hosts Sunday film nights in the summertime at the Beverly Cañon Gardens, a pleasant strip of grass between a swish hotel and an even swisher French restaurant, where I briefly allowed my mouth to water over a $22 plate of charcuterie that I did not purchase. The children on the green dangled their legs from folding chairs and were rapt. They had been regaled two weeks before with School of Rock — for me, one of the great modern parent-kid bonding films and probably the greatest thing Jack Black has ever done. This week, in honor of the quatorze, the city’s cultural arbiters had chosen an animated French film about a middle-aged bear and a very young mouse. Its title was Ernest & Celestine, and I fell for it, hard and quickly.

Nominated for the 2013 best animated feature, Ernest & Celestine is delightful to look at — simple figures pulled from the original children’s books but animated with the quick-frame, occasionally frantic pace of animé. When we arrived, Celestine (the very young mouse) was on the receiving end of a horror story about bears, delivered with a bit too much sadistic enthusiasm by a prefect at the orphanage.

“… and then the big bad bear eats all the mice!”

“Even when they’re raw?” asks Celestine, pulling the bedclothes tight.

“Especially when they’re raw,” her wizened admonisher returns.

Soon, we see that the bears have their own, similarly embellished stories about mice. Once Ernest and Celestine become friends, the message begins to ring: down with xenophobia, up with compassion, keep an open mind, be kind to children.

But then there are the teeth. Let me explain the teeth. Celestine’s orphanage is really more like a Victorian workhouse, or a version of Fagin’s street-gang where child-mice are expected to steal lots of bear-teeth. The older, richer mice then use the bear teeth for lucrative orthodontic purposes (mouse-incisors, apparently, have a habit of falling out). In the bear world, meanwhile, the principal characters are a consumerist nightmare: papa bear gets the younger generation hooked on the rich, gooey offerings at his candy store, and then mama bear fills the resulting cavities at her dentist’s practice across the street. “Supply and demand,” papa bear says, when his son asks about the family businesses. “We do both.”

The Marxist underpinnings of this story cannot have escaped the notice of reviewers, but to me — on Bastille Eve, with a head full of sun and stone and tricouleurs in every direction — the baldness of the subversions seemed perfect. In one tableau, the bear police pinch Ernest for panhandling (a one-man-band, he sings about how hungry he is). The first gendarme takes away all of Ernest’s instruments, while the second issues Ernest an enormous fine. And isn’t that always how a police state operates? Demanding punitive sums while taking away one’s ability to work? But that’s not the real Marxist thing — the Marxist thing is the teeth, which serve as connective economy between the mouse-world and the bear-world, and as a means in each of suppressing an underclass and solidifying power among the already-powerful. Ernest and Celestine learn to reject fairy-tale, irrational, politically ginned-up paranoia. Their real lesson is that regardless of borders, your loyalty is to your fellows in oppression. Squint slightly, and you’re looking at Marx’s notion of a permanent global revolution.

As I said, the dissonance was perfect. Squeezed between such cathedrals to opulence, a dozen or so children absorbed a film that would have been banned in the days of Joseph McCarthy, a bloodless argument for the same égalité and fraternité that Robespierre, et al. championed two and a quarter centuries ago. Next door, forks made hollow noises on traditional French plates, and the small arrangement of charcuterie continued to retail for $22. The parents seemed pleased. Perhaps they thought the film offered a salutary message about dental hygiene.