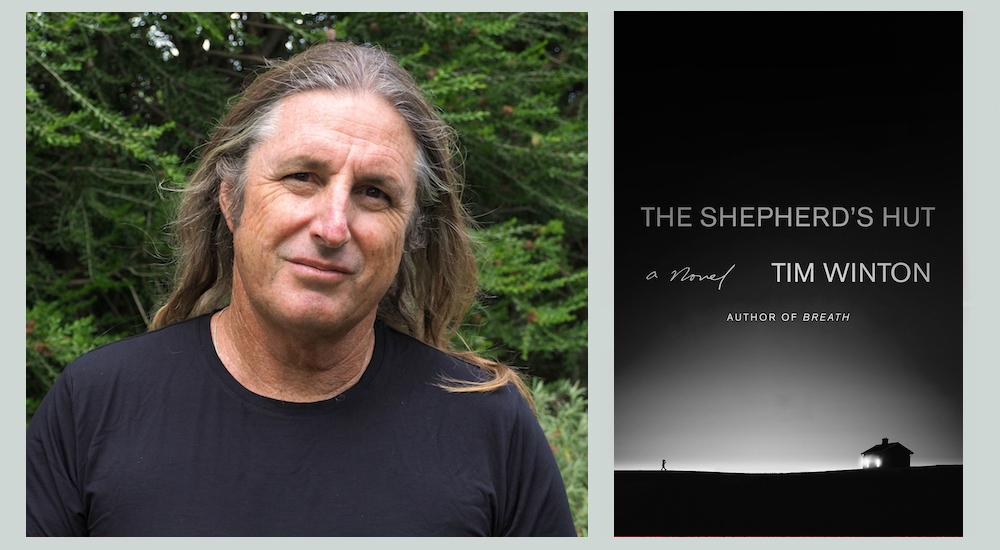

Tim Winton is one of Australia’s most decorated novelists. Over the course of a long career, he has successfully combined popular appeal with literary accolades. Born, raised, and living in the southwest of Western Australia, he writes about this land and its people as an imagined place and community, often engaging with themes of violence, desire, and belonging. Winton’s many prizes include four Miles Franklin Awards, two Man Booker short-listings and a Centenary Medal. In 2007, he was named a National Living Treasure. For a long time, Winton has participated in community activism. After appearing at the Perth Writers Festival, we caught up to talk about the American release of his latest work, The Shepherd’s Hut.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: Looking back on your work to date, it feels like you have always been interested in place, nature, and relationships. Were you aware of these interests early on? Did they simply reflect what you saw around you?

TIM WINTON: Well, I always loved books in which place was significant — paramount, even. Maybe it stems from growing up in a no-account place — on the wrong side of the wrong continent in the wrong hemisphere entirely — and feeling a kind of loyalty to it in the face of indifference or even contempt. I guess many writers with regional or provincial backgrounds are attuned to this. I’m sure it’s why I responded so instinctively to writers from the American south, or the Irish, or Celtic Canadians. I loved the particularity, the intimacy, as much as the vernacular music. And as for relationships, I think I was schooled in this in a geographical sense. I was always interested in the natural world, but my education was modest and conventional; it was all about separating and cataloguing, which is of limited use, and sometimes worse than limited — it’s distorting and untrue. But in the end lived experience superseded this narrow view and I learned that nature is essentially about relationships, skeins of dependency and connection. And landscapes and communities are too. Looking back, I see this little revelation as fundamental. As you say, these relationships between people and their place and their ecology are what the work is about.

Your new novel, The Shepherd’s Hut, continues some of these previous concerns but does so in a new way. Can you tell us about the book?

The story is about a 15-year-old borderline sociopath who finds himself suddenly orphaned and then lights out for the territories, so to speak. His name is Jaxie Clackton and he’s from a tiny town and a violent family, and much of this novel is about his flight from home and his trek through the goldfields and salt lands of Western Australia. He’s in love with his cousin. He’s hiding out initially, lying low a while before striking out north to be reunited with her — a journey on foot of 250 miles or so. Along the way he bumps into a stranger, a ruined priest who’s in flight from his own moral disasters. When I put it like this, it all sounds pretty Gothic, but I never thought of this in Gothic terms because, given the place and the folks I’m writing about, it’s not particularly outlandish. I guess the further back you stand from it, the more lurid it looks. The story’s told in Jaxie’s profane and unschooled voice, and at first he sounds pretty feral, but after a while that strangeness fades. You go with it. At least I did! Sometimes I really felt at this little scumbag’s mercy. Even though he’s just a confection.

Like all my characters, Jaxie springs from the ecologies of the story. The place came first, as it always does, and the landscape determines the parameters of the story; it throws the people up (one way or another) and they’re what and who I have to work with. I guess by now I’m used to submitting to the environmental logic underpinning it all. The figures literally emerge from the landscape.

I think landscape has the ability to make voices — it is bedrock, loam, compost for thinking about tone. One of the greatest strengths of The Shepherd’s Hut, and something that could be said of many of your novels, is the ability to inhabit a narrative voice. It often rings true and helps locate the reader firmly in a world. How do you research and write different voices, and where does this fit with your writing practice as a whole?

Well I wouldn’t dignify what I do as a practice. After 30 years it’s mostly a habit. Which is why not much of the mulch underpinning it can really qualify as research. I guess I just watch and listen without purpose. And I’m strangely placed, socially (which is probably an understatement) because I come from the unlettered working class and spent my youth in the country. I was lucky to be able to go to university. I was the first in my family to even finish high school. And although I’m now middle class and educated, I don’t live where folks like that usually live, which is both uncomfortable and advantageous. I spend most of my life in small, isolated communities where the social norms and mores are not exactly in tune with the metropolitan dispensation, if I can put it that way. I don’t have to do any research — I’m marinating in this stuff. Most of my friends and neighbors would be viewed by city folk as rednecks. Someone as déclassé as me has to contend with complicated loyalties and instincts. Socially you learn when to hold ‘em, when to fold ‘em, and when to walk away. But on the page you have to hold them come what may; there’s no compromise. You have to back yourself imaginatively (and artisanally) and that requires the kind of nerve you have to manufacture daily, because you don’t always feel it naturally. Basically you have to be prepared to tell the reader to like it or lump it; there’s no room for politeness and no point in compromise. The world of the book needs no social licence, no instrumental excuse, and it should give no quarter.

The perspective in the book allows you to speak a kind of truth, and in that way The Shepherd’s Hut often has a kind of violence, a taut and tense quality, a kind of darkness. The book has an edge — to the men, to the landscape, to the fate that befalls certain characters. I am thinking here too, of your understanding of the Southern Gothic from William Faulkner onwards, and how that frees one up to write of place. Can you talk about violence, the Gothic, and our place in the world?

I have a personal horror of havoc or physical violence, which is a legacy of childhood, I guess. Not that I was a victim of violence. But my old man was a cop and I was exposed to stuff outside the home that had a lasting effect on me. And I had a kind of window into the lives of others that only the child of a small-town cop will probably have. You learn things you shouldn’t know at an early age. I suppose as a kid you trust that the grown-ups know what they’re doing, so it’s a shock to realize they’re just making it up as they go along, and they’re subject to impulses and passions that render them either stupid or dangerous, or both. There’s no question I learned about the weird electricity of masculinity this way. That perverse and ever-present current that snakes about like a cut live cable, seen and unseen. I’ve been writing about that queasy mystery for a long time. But I’m also interested in the violence of passion and sorrow. Liam Rector’s line, “change is hard, and hope is violent” has stayed with me and troubled me for years. Which might explain why it became the book’s epigraph. Liam was a dear friend. And that line acknowledges the evolutionary fact that change requires or creates breakage — of ideas, states of mind, institutional conditions, as much as emotions and bodies and organisms.

Having said all that, Jaxie does come to an existential revelation during this story: that despite all our instincts to be makers and creators and lovers and nurturers, humans are breakers, takers, killers, too, creatures doomed to feed on other living things. Only the most privileged or deluded among us can ignore that. Someone in his predicament has to face it and yet somehow strive to surpass it. He doesn’t have the luxury of pampered denial. I think I learned more from Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy than Faulkner, who I loved, by the way. And I was an early adopter when it came to Cormac McCarthy. Still have my first copy of The Orchard Keeper. Though the nihilism troubled me. Late in his career, though, he seems to have reached a point where his characters strive to create the conditions of hope and grace where neither of those seem evident or even possible. That’s a big step up from nihilism; there’s fresh courage in that and it certainly rings my bell. Yes, life is riddled with havoc and hope is violent, but hope is also necessary and by our actions it can be made and nurtured in the face of all horrors. Which probably isn’t a Gothic view, or, perhaps a Southern Gothic view. Once upon a time it wasn’t a McCarthy view, either. In the old days it was no change, no hope, only the dread certainty of violence. As to “our place in the world,” the end of The Road is telling. You hand your children on to strangers and trust they won’t eat them. There’s hope for you.

The Shepherd’s Hut has a firm grounding, which some other critics think of as quintessentially “Australian.” But it is also an imagined location, a location of the mind that is more specific than a nation. Can you speak of the relationship between real life and creative landscapes? Of being firmly positioned in a place while also expressing a fictional idea of what that might be?

I don’t even know what “quintessentially Australian” can even mean, to tell you the truth. There are 22 million ways of being Australian. And 326 million ways of being an American. I’m a storyteller, a tradesperson. I’m making stuff up, concocting a world in my head and on the page, from story to story and book to book. And that fictional world obviously owes a lot to the continent I belong to and the people who’ve helped form me as a person. But it also owes plenty to all those books and stories that came before, and the mythic swamp all of us swim in, and that transcends all kinds of borders. I don’t seek to represent my place and my people. I’ve always been happy — actually stubborn to the point of bloody-mindedness — to own my place and its smells and sounds, and to speak in a voice that doesn’t defer to London or New York. For many years, that really cost me in the northern hemisphere; it cost me in my own country to a lesser degree. It was my youthful instinct to stay and fight. But my hope is that readers believe in the fictional world of the work, that they perceive it as authentic in itself.

It certainly seems authentic and I guess that makes me think about realism. But, this conversation between grounded reality and an imaginative world is there in other aspects of your life, including in your involvement in conservation, class inequality, and toxic masculinity. How do you see the public role of novelists as activists, spokespeople, teachers?

Although I am pretty active as an extra-curricular advocate, I don’t think the novelist has any responsibility beyond what’s on the page. To me, art has no instrumental value; it needs no other excuse to defend its existence. I’m all for useless beauty — that’s more than enough for me. So everything I do as an activist is just normal citizen work. I do what I can to improve conditions as a normal punter, as a father and neighbor. Art affords me no special wisdom and it confers no special responsibility. What my work has brought me, which is as amusing as it has been unlikely, is a kind of cultural prominence in my own country. Most of that prominence is fairly bogus, as is most celebrity, but it is a form of currency (and most currency is laughably artificial, isn’t it?) so I figure I might as well spend it the best way I can. Life is more complex and perverse and rewarding than any novel. Working in the real world takes more nerve and more imagination than writing. Which is why you need comrades and help and group discipline to get things done. For a lone dog artist, that’s an education all on its own, finding that stuff out. So, I do my citizen work and then retreat to being a weirdo who spends all the work day with folks who don’t even exist. I dream about these imaginary people. This is not normal. And yet after 30 years nobody has come to cart me off. If only they knew.