When did democracy become a form of “politics for old people”? When might middle-aged and older voters now need to provide our most far-reaching progressive vision? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to David Runciman. This present conversation focuses on Runciman’s lecture “Democracy for Young People.” Runciman is a professor of Politics at Cambridge University. He hosts the weekly podcast Talking Politics and writes regularly about politics for the London Review of Books, where he is a contributing editor. His most recent book is Where Power Stops: The Making and Unmaking of Presidents and Prime Ministers. In 2018, we discussed Runciman’s book How Democracy Ends.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you sketch some key dynamics in recent UK/US politics (as manifest through Brexit and the 2016 Donald Trump election, Boris Johnson’s December victory and the 2020 presidential campaign) often overlooked when analyses fail to address the fact that our democratic process has become a form of “politics for old people”? What most pivotal shifts in voting patterns and corresponding policy choices might we all still fail to grasp as electorates grow much older, as older voters remain active much longer, in ever-increasing numbers? And specifically for left-leaning political parties conditioned to calling for significant structural change, can you give recent or historical examples of such calls resonating quite positively among older voters?

DAVID RUNCIMAN: Across recent elections we’ve seen that a voter’s age is a stronger determinant of how that person will likely vote than income, class, or gender. The older someone is the more likely he or she was to vote for Brexit, for Trump, and in the recent UK election for Johnson’s Conservatives. The only factor comparable to age is education (the more education, the less likely that someone voted for any of those outcomes). But we should remember that education itself can operate as a proxy for age (the older a voter, the much less likely that this person went to college). In the UK, less than five percent of people over 65 attended university. Among the under-thirties, that figure is close to 50 percent.

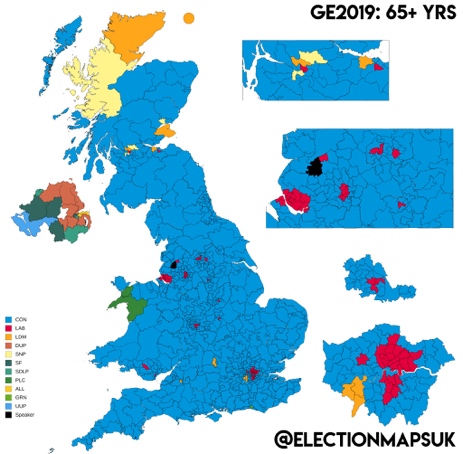

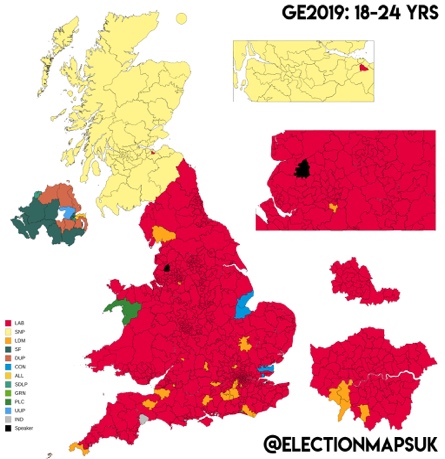

The 2019 UK election brings out this age divide very clearly. The first of the two maps below shows how the constituencies would have gone if only the oldest age cohort registered by pollsters (the over-65s) had counted. The second map shows how these constituencies would have gone if only the youngest cohort (18-24 year-olds) had counted — and you need to remember that our red and blue differ from yours: the second map shows a Corbyn landslide!

Maps by Election Maps UK.

Among the older group, 62 percent voted Conservative and 18 percent voted Labour. Among the younger group, it was almost exactly reversed at 19 percent Conservative and 57 percent Labour. The primary reason Conservatives won this election is that today the UK has many more people in the older age group, and they turned out to vote in higher numbers. But the basic divide is clear. It’s like Disraeli said in his 1845 novel Sybil: “Two nations; between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets; who are formed by a different breeding, are fed by a different food, are ordered by different manners, and are not governed by the same laws.” Disraeli, though, was talking about “THE RICH AND THE POOR.” We are talking about “THE OLD AND THE YOUNG” (and also, as these maps show, we are actually talking about three nations today, because in terms of voting, Scotland has become almost another country from the rest of the UK — yellow is the Scottish National Party).

This divide makes a big difference for policy choices. In the UK, pensions will get protected, even for wealthy pensioners, but student debt won’t be cancelled (which is what Corbyn, like Sanders, was offering), not even for poorer students. And it’s not that older voters don’t care about education, but that they are much more concerned with primary than secondary education, and with what they see as declining educational standards rather than rising tuition costs — and they are more concerned with healthcare than with either. So healthcare costs get protected too.

The policy divide gets even more stark when it comes to climate change. Those two age cohorts (18-24 and over-65) diametrically disagree on how urgent the climate challenge is, and whether it requires radical action. The Green New Deal, another flagship Corbyn/Sanders idea, has much appeal for younger voters but much less appeal for older voters. Since neither country has enough younger voters to deliver on this policy proposal (as Corbyn discovered), it is not an election winner. So policies like these either need to be qualified, or buttressed with something else to appeal across the age divide.

Previous left-leaning policy agendas have not been so caught up by this age dynamic. In the UK, Tony Blair appealed to older voters as much as (and in some cases more than) to younger ones. Blair was of course a centrist, but going further back, politicians like Attlee in the UK or FDR in the US won big election victories by attracting older as well as younger voters to the cause. Here again though, we need to remember that when you go further back, the demographics shift fundamentally. FDR first won in 1932, with less than five percent of the US population over 65 (compared to 17 percent today). To win from the left in the 1930s, you didn’t need many old people. Today you do.

So let’s say that democracies long have sought to limit the impact of younger (supposedly less responsible) voters. Let’s say that representative democracies have, by design, constrained prospects for young people to win elections. And let’s say young voters’ perennial sense of inadequate representation stings even more acutely now, since (again for the first time in history) if all the young voters gather together, “they lose.” For all of these reasons, one can understand how frustrating it becomes for young people to keep hearing from all sides that they must provide the long-term vision for our society’s most humane and sustainable future — precisely as, in current political contests, an unbeatable-seeming bloc of older voters continues prioritizing its own short-term interests. What range of responses do you see from young voters facing such a diminished democratic share today?

Representative democracy does have, as you say, built-in barriers against the representation of younger voters. These barriers come out of the assumption that young people will normally have the numerical advantage. Yet these obstacles remain, even now when the numerical argument no longer applies. The biggest obstacle comes from the difficulty of getting elected as a young person — almost all parliaments and legislatures have a preponderance of older representatives (with, in this case, age often operating as a proxy for wealth). Ironically, the recent UK election has seen a greater number of twenty-something MPs than normal, but most of these are young Conservatives in Northern seats, who won precisely because the areas they represent have seen an exodus of younger voters to the cities. Older voters elected these young MPs, almost like a mirror image of the Sanders or Corbyn projects, where old men try to win power off the back of young supporters. If the UK parliament ends up with a “Squad,” it won’t be anything like the AOC crew. It will be a pro-Brexit, pro-pensions, anti-Green New Deal group.

I have long felt that representative democracy has become doubly unfair for younger voters. Not only do they keep losing elections (which means that their interests often get neglected), but they also are expected to be the group that offers a vision for the long-term, and that articulates the concerns of future generations. How can you speak up for people not yet born, when the system won’t even let you speak up for yourself? One possible response on the part of perennial losers of course is to disengage. Low turnout rates among younger voters do not necessarily confirm that this group is lazier or more feckless, as older voters sometimes think. Instead, these rates might come from more young voters considering it futile to vote. If you keep losing, why bother to play the game?

Young people also sometimes respond with anger, and not just in Western democracies. Young people’s anger has become increasingly visible in places like Hong Kong, Iran, Lebanon, Chile, and many other countries where we’ve seen an increase in street protests, usually led by the young. Of course, young people are inherently more likely to do street politics — with rioting not really an old person’s pastime. But in each of these cases, you also see political systems that have failed to adapt to the fact that rapidly aging societies radically disadvantage their younger citizens, who nonetheless will have to live with the long-term consequences of the choices being made today. We tend to think of aging societies as a problem for the old, who will need looking after. But the young, who will need to do this looking-after, even while being systemically disadvantaged by a system that favors their parents and grandparents, face even bigger problems.

In Hong Kong, tensions have emerged through the demand for more democracy. But in Western democracies, these tensions sometimes emerge through a demand for less democracy. Survey evidence suggests that the greatest disillusionment with democracy in the West (and the greatest temptation to seek alternatives, including more “strongman” politics) comes from younger voters. So this is everybody’s problem.

So with numerous national electorates now holding (or soon to hold) majorities of middle-aged and older voters, what case might you make for these groups to recognize their own responsibility to promote a civic-minded, sustainable, future-oriented politics — not because of group members’ age necessarily, but because members embrace the duties that come with being the demographic fulcrum of our democratic culture?

That seems to me the crucial question. We spend too much time thinking that an election will fix this, if only we can find the right candidate to bridge the divides. Barack Obama did manage to bridge some of these divides, but there’s only one Obama (at least until his wife runs). Political parties should be the institutions for brokering these divisions, but at the moment our parties only seem to make the situation worse, either because a party gets associated with one particular side of the divide (the Republicans), or because the party itself gets divided on generational lines (the Democrats). Joe Biden has a decent shot at winning a general election against Trump because Biden’s appeal skews towards older voters. But seen by younger Democrats, that’s what confirms Biden being such a flawed candidate — appealing to older voters is the only way he can win. Sanders, despite being an old man like Corbyn, doesn’t have that problem. Their problem is that younger support gets them nowhere near enough votes. For now, again, each election seems just to make these problems worse.

So we should make the case that the perennial winners in elections (and within political parties) have special obligations to think about the losers. Part of the problem here is that older voters may not see themselves as perennial winners, because this is a relatively recent and still relatively hidden phenomenon. Older voters often feel disadvantaged by democratic politics, with many of the most popular communication tools in the hands of the young, particularly when it comes to new media. But democracy remains a numbers game, and the numbers increasingly favor older generations. The other problem comes from those divides that Disraeli identified, with the two sides experiencing life very differently: “different habits, thoughts, feelings.” Our societies have developed a serious absence of shared understanding. Again, we may overlook this divide, because we still often see the different generations live in proximity to each other, especially inside families. Unlike with the divides between urban and rural, or secular and religious, or Republican and Democrat, or college-educated and non-college-educated, or white and non-white, we don’t here see the same literal lack of contact. All old people know some young people, and all young people know some old people — whereas for many of these other divides, almost no interaction at all takes place. But how the different generations interact still matters greatly. And politically productive conversations across the generational divide are increasingly hard to come by.

Some civil-society organizations are trying to address this, for instance Gen2Gen. I think “show don’t tell” offers a good guiding principle here: it won’t help to tell older voters that they have a duty to the young, but it would help to show older voters how the young see democracy at present. And that means, above all, doing democracy also outside of elections, and finding other ways than voting for the generations to interact.

More broadly then, as certain electorates’ median age approaches the “Golden number of 50” (the typical median age of parliaments throughout political history), how might this transformation of the polity make our politics perhaps less paternalistic (with less need to defer to authoritative elders), less fraught (with less cause to consider well-educated elite representatives categorically distinct from the rest of us), more frustrating (with little rationale for office-holders so like ourselves to monopolize political decision-making power), and/or more fractured (with democracy’s most salient divides now coming not from unbreachable gaps between an electorate and its representatives, but from polarized demographic differences within the electorate itself)? How might, for instance, an increasingly embittered political rhetoric directed by young citizens today at baby boomers, prioritizing claims of intergenerational injustice, provide one quick glimpse at what future (more internalized) crises of legitimation may look like for representative democracy?

Well, I don’t envision a civil war between young and old (though if one does break out, despite their numerical disadvantage, I’ll put my money on the young). It’s not that kind of divide. But as you said, these divisions and tensions will likely play out in a whole variety of ways. We see some of what may be coming with the Greta Thunberg phenomenon, where she basically makes the case that decisions about the future can’t be trusted to our political representatives, because they are too old to care much about what happens in the long run. I consider that a bad argument. I don’t believe that the older someone gets, the less that person cares about the long-term future. I think we all (young and old) have problems imagining the long-term future, but at the same time we all care about it.

The difference in perspectives here has a lot to do with experience. People who have, for instance, lived their whole lives in a fossil-fuel economy find it harder to imagine a different way of living than those who still have most of their lives ahead of them. This partly becomes a question of loss-aversion: giving up cars sounds much harder if you have long had a car, versus if you have never had one. That doesn’t make older people (including older politicians) more selfish. But it does make them different.

Representative democracy assumes our elected officials will differ from the wider population — older, wiser, richer. Though as the population ages and gets more educated, this argument starts to break down. For older voters, today’s representatives don’t look so different from them, so they start to wonder why these politicians get to make all the decisions. For younger voters, representatives look so different from them that they also start to wonder why these representatives get to make all the decisions. For one group, familiarity breeds contempt. For the other, distance breeds contempt. But in both cases, you see a demand for more direct democracy. The Brexit referendum and its fallout came in part from voters wanting more of a say over the big decisions that affect their lives. I see this demand for more direct democracy (for more decisions being made by the people, not just for them) growing. I think one consequence of our society’s overall aging will be representative democracy coming under more and more strain. Rising populism offers one clear manifestation of this, with politicians who claim to give democracy back to the people, while in reality exploiting divisions among the people. But I think in our preoccupation with the economic causes of populism, we sometimes miss these even bigger trends — it’s the demography, stupid!

I also see a big difference between age and education when it comes to representation. Older cohorts who did not attend college can outvote both the young and the college-educated — so Brexit wins, Trump wins, Johnson wins. Yet even after these wins, our representative institutions still remain overwhelmingly dominated by people with higher-education experience. Every single member of the US Senate went to college. 90 percent of British MPs went to university. But there are no US Senators under the age of 40. Still fewer than two percent of MPs are in their twenties. So our parliaments and legislatures overwhelmingly overrepresent the educated. But they even more overwhelmingly exclude the young. That is one reason why I believe the age gap, though closely related to the education gap, matters more. The unfairness is greater. In our democracies, the young are the biggest losers.