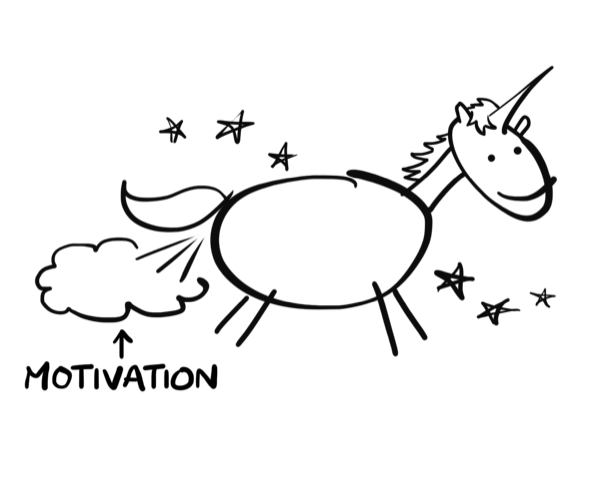

Mark Freeman’s book You Are Not a Rock: A Step-by-Step Guide to Better Mental Health (for Humans) (Penguin Books, 2018) is not for the faint of heart; it’s not for those who are in search of some sanitized positive thinking to soothe their feelings of self-doubt. Instead, he urges readers to “Stop coping,” “Stop checking,” and “Break your motivation addiction,” outlining specific exercises that readers can do to improve their mental health. He developed these exercises in his own recovery from various diagnoses, but this book is not aimed at readers with any specific mental illness. Rather, Mark creates a framework for understanding mental health that can benefit anyone. He writes, “Mental health is the practice of being yourself. Improving your emotional fitness enables that practice so you can feel whatever you feel while being yourself.” Through his firsthand experiences, including with mindfulness practice, he has discerned concrete actions that can help a wide variety of people with idiosyncratic goals, because many of us face struggles with similar components: we want to avoid unpleasant experiences like uncertainty, anxiety, and fear. The desire to avoid these experiences, Mark writes, leads us to develop compulsions that keep us chasing a state of unfeeling and certainty which is actually unreachable, rather than our goals and values.

Mark’s mission to help people improve their mental health, to “practice being oneself” is rooted in the analogy of mental and emotional fitness: he writes, “We’ve made physical fitness accessible. We have to do the same with mental health, for everybody, because everybody has a brain, and those delicate imagination organs jiggling around in our skulls are chronic.”

As a creative person and a writer, I am in a habitual state of struggling to make progress on one of any number of creative projects. This often feels distressing. (Perhaps others can relate.) You Are Not a Rock got me meditating again as well as growing my capacity to experience discomfort, which I suspect may be a foundational skill to the act of writing — at least it is for me.

I shared with Mark some of my frustrations with writing — including but not limited to, difficulty focusing, setting goals, and establishing a schedule. We discussed the role of creativity in mental health and how the exercises for mental fitness in You Are Not a Rock can apply specifically to writers and other creative types.

¤

LAUREN KINNEY: I found when I was a student in an MFA program that I was learning a lot about writing craft, but often when I would sit down to write, I felt like I couldn’t do it, or I couldn’t focus and I wasn’t sure how to build the inner resources that I needed to be able to write.

MARK FREEMAN: I can completely understand that. I took some creative writing classes when I was getting a degree in literature and I knew I wanted to write. Looking back now, so much of what we don’t tell people in creative writing classes was also what was missing when I was doing therapy at first. We just expect people to do this stuff, and we don’t really tell them how to do it, how to cultivate those — I like the term you used — inner resources. We struggle with all these uncomfortable feelings, ways we’ve learned to cope, and ways we’ve learned to approach the creative process, approaches that maybe worked for us in the past but now actually get in the way of doing the things we want to do. Why does nobody teach us about how the hell you actually write?

I know that everyone has to grapple with that. I think it’s commonly acknowledged that writing is emotionally taxing, and I suppose everyone needs to figure it out on their own, but I wonder how my MFA experience would have been different if I had been meditating, or been approaching the creative process in a different way at the outset.

I think that it’s great that we’re looking at this stuff now, because I think we used to just approach creativity like you just magically pull it out of this box! But it is such a mental process, and if we’re not learning how to handle the stuff our brains throw up, it gets in the way of writing. Sometimes our brains can be limiting. It can be like, Oh, you shouldn’t talk about that because it’ll make you anxious or you’ll be embarrassed about that, when actually that is the stuff we should venture into. Learning how to see through the barriers the brain throws up, whether they’re thoughts or emotions, is so useful to us in creating new, exciting things that align with who we are and what we care about.

Do you work with a lot of creative people in your mental health coaching practice?

I just got off a call with a music producer, actually. It has been a day of thinking about exercises around creativity. There have been a lot of performers, but, you know what? Maybe one writer.

What sort of things do your clients struggle with and what sort of advice do you give them?

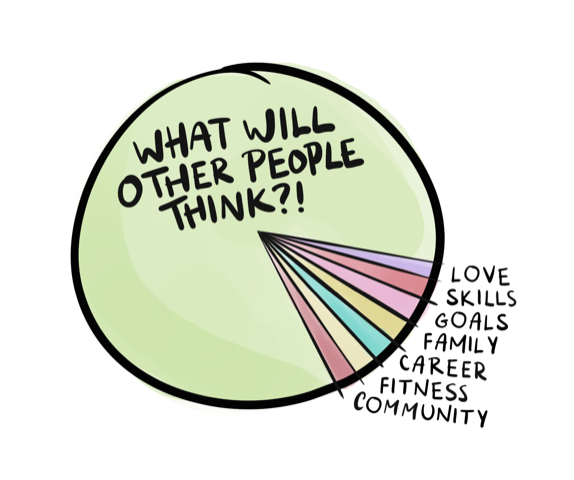

Everybody struggles with the same stuff, but especially when people are being creative, a lot of fears around what other people will think can start to interfere with the work. Even if somebody is anxious about something like germs, often we can trace that back to a fear of what other people are going to think — If I spread a disease and people die, everybody will hate me. We’re social animals, so we really care about what other people think. A creative profession sometimes pushes people naturally into scenarios that can be unhealthy, like if they’re constantly having to send out content to see what people think about it.

Especially when people are doing creative work, it’s so important to keep success close — keep success under your control — and also stick with values. This helps us push into that anxiety and do something that’s really creative, pull ourselves out of our comfort zone, and see through the fear.

It’s easy for me to set goals — I have a million goals. The “values” part is a little more challenging. Do you have advice on identifying your core values in a way that moves you forward and “keeps success close,” like you said?

I’ve worked on being able to accept that I’ve created enough. I think sometimes, too, we can feel this pressure of having to do more, like we haven’t done enough. Through understanding my core values, I drill it down a bit.

I focus on creating tools that make mental health accessible to people, which is flexible enough that I can do different things. I can do books, I can do videos, I can do podcasts. But all the things I work on share the element of making mental health accessible to people. I think, Okay, if I do this, is it going to help people? What’s going to help people the most?

That value helps push me out of my comfort zone and keeps me learning skills. So right now, I’m working on a podcast, and that’s because a lot of people were telling me, “I just listened to your videos — I don’t actually watch them.” So I was like okay, a lot of people are listening to audio content, and there’s a lot of interest in it right now, so that’s something I’ll learn how to create. Nailing down a value there does give me a way to make a choice. Considering which thing is going to make these ideas more accessible to people and reach the most people helps guide me.

I also find it’s really important to tie my values to an action. Particularly with being creative, I find it’s useful for that action to be public. I’ll track things like how much did I write and post online this week? That, too, helps me make decisions because if I see my schedule for the week is just working on a new book, then I know I’ve got to add in some extra creative time to make stuff to share, because if I’m just off writing on my own, it’s easy for me to get off track.

That makes sense to me.

That makes sense to me.

How are you tracking when you’re working on a novel? How do you keep yourself on track there?

[Laughs nervously.] The only way that I’ve measured myself and the way that I actually started trying to write novels was doing NaNoWriMo. That’s basically a monthly word count goal, which I would break down into a per diem goal, but it’s more taxing than I can do on an ongoing basis. I like that approach because it forced me to turn off my analytical mind, which is helpful, but then I have 50,000 words that I need to revise, and I’ve never known how to proceed from there. Now I’m trying a different system that I’m hoping will also hamper my analytical mind. I’m taking the story and, without looking at my first draft, I’m trying to outline it from my own memory while imagining the story again. But it’s been really slow going because I don’t have any measurable goals. For a while, I was making myself wake up early to write before going to work, which a lot of people say that they do, but I found that I couldn’t do it. I just really wanted the sleep.

Sleep is good!

These are the kinds of things they should spend a whole year on in the MFA program. We end up having to figure stuff out on our own. Learning how to juggle the job and the creative project, which so many creative people are having to do, creates a lot of challenges, too. In You Are Not a Rock, I write that so much of mental health is how we spend our time and energy being ourselves. It can also be very exhausting if we’re running back and forth between different selves. Even though we have to do it, it can be so stressful. I think that makes it even more important to have a process and a practice, because we’re essentially working two jobs. Or three jobs, or four jobs.

One of my fears is not finishing a book before I die.

Yes! I have that, too. I used to do all sorts of compulsions because of that.

Like what?

Basically, I wouldn’t be writing anything. I’d be spending all of this time on all sorts of other things I hated. And then, say a trip was coming up, then I would be like Oh no, I’m going to die on the trip, but also I’d be convinced, like, thieves would break into the house and light it on fire or something, and all of my work, all of my notebooks, my unfinished books would be destroyed.

Oh, that’s so bad!

It was always so obvious, the connection between not creating and the rest of my mental health struggles. Part of the practice of taking care of my mental health is creating. If I don’t do it, my brain hates that, even though my brain is the thing getting in the way of the creating.

I love that, thinking of creating as mental health practice, and it’s not because you’re expressing yourself necessarily, it’s because it’s something that you value.

Exactly, and you’re afraid to lose it. It’s like, your brain is watching you, and it’s like, Oh no, we haven’t done this thing we really value…

How did you move from working on your own recovery to supporting other people’s mental health, and where did writing your book figure into that?

This book is a product of itself. These techniques in it are what helped me take care of my mental health, be able to work and write at home, and get stuff done. I noticed I was struggling with my mental health when I took some time off to write a novel. I think I maybe took six months and finished nothing. There were all sorts of other, obvious mental illness symptoms, but I was so delusional, I didn’t recognize them. I was watching the stove to make sure it didn’t spontaneously combust. I thought people were trying to poison me — not an issue. But when I couldn’t write, I was like, Oh, this is a problem!

I was not able to write a novel. I could see I was spending the whole day on compulsions, and then the day would be gone. Getting into this was a process: learning to take care of my mental health and getting over a bunch of mental illness diagnoses. I always thought I would just be a fiction writer, but I went this way because I saw there was such a gap between where the science was at on recovery from mental illness and what people are generally accessing. So right now, my plan is that the next three books will probably be nonfiction books in the mental health world.

There are a bunch of exercises in You Are Not a Rock about learning how to write on the bus or going to noisy shopping mall food courts to write important things. I had to do exercises like that to be able to write and publish anywhere, and that was part of turning off that analytical mind. Saying On this bus ride, I’m going to write something and publish it at the end of this bus ride, no rewriting or rereading.

That takes nerve.

It also transformed my writing practice. In the past, I would’ve always said I was a rewriter. I rewrote everything. If I sent somebody an email, I could spend all afternoon crafting the email, rereading and rewriting it. So it helped me to see that was part of the compulsions that were fueling my mental health struggle. I had to change how I wrote completely.

I remember that in your book. I’ve been trying to just press “send” on my emails lately.

My favorite one is going and writing in weird places. That’s a super fun one to do, to pick the worst possible imaginable place to write and go and write something and publish it.

I haven’t tried that. I have written in a lot of places, but it’s usually cafes.

They’re nice, right? It’s like learning to write in a cafe, just the opposite. The places we think of as “contaminated” places are great to write in. If somebody has a particular hatred for a fast food restaurant that they think is gross and would never eat there, that’s a great place to go and write something beautiful.

Learning how to write in noisy places was really important to me, because I had a lot of compulsions around noises. There were lots of sounds that would give me a very physical reaction, so I worked on going to noisy places, places where I knew I’d be annoyed and bothered constantly, to write. That was really key for me. That’s such a great skill for learning how to not listen to your brain.

It’s great to learn how not to react to, I don’t know, the person who’s shouting beside us, because we’re like, Okay, that has nothing to do with me; I gotta get down to writing. That is such a useful skill to then apply to your own brain. My brain’s shouting at me right now; I don’t have to listen to me; I have to get down to writing.

I’m not sure that I’m aware of that many compulsions that I have around my own writing. I just know that it’s really hard to force myself to do it. It makes me want to uncover more of them so that I can fly in the face of them.

That’s really the way to approach it. We don’t want to get caught up in having to find a problem and then fix it. It’s like learning to swim. Like, This is kind of difficult for me right now. I know it’s possible to swim, so how can I get in the pool more, get in the water in more places? Push the thing that’s difficult for my brain? With all of this stuff, whether we look at it as mental health or creativity, it’s so much easier when it’s about celebrating and building rather than trying to fix a problem, because our brains love finding problems.

You mentioned earlier that you are trying to fill gaps in mental health care that people are most commonly accessing, what are some of the gaps that you’re working to fill?

I would say the main gap is, what do you do when you’re not with your therapist? It helped me to recognize that change is difficult for all humans. Forty percent of the people who joined a gym in January are not going to the gym by June. And we don’t label them as having a disorder, or they’re “exercise resistant” or something like that. But in mental health, you’re often required to make really complex changes at the most difficult points in your life. And maybe, if you’re lucky, you’re seeing a therapist maybe once a week for an hour. When we’re struggling, the reality is there’s so much that has to change in our lives, because we’ve built our lives around the mental illness — to facilitate it. So if somebody says, hey, you have to change this thing, actually our whole lives are designed around not changing that thing — continuing to react to anxiety, find problems, control uncertainty, and so on.

That was one of the reasons for making a book. You can have it, and the exercises in it, anywhere you go. It can be there when you’re wondering, What do I do with my brain right now?

Using that metaphor of emotional fitness, if one of your goals is to complete a writing project, would you consider writing an emotional fitness exercise?

Oh, absolutely. Every time you sit down to write and your brain is saying, What about this feeling right now? You should go and solve this! You should go and do that! it’s absolutely a mental fitness exercise to confront whatever it is your brain’s throwing up, accept it, and do the thing you care about.

I think it’s important for people to realize, too, that you can’t just jump in and do it all. It’s like learning how to run, learning to say, Okay, actually, today I’m just going to feel uncomfortable and write for an hour, and I don’t have to make that uncomfortable feeling go away, and then tomorrow I’m going to do it again. We have to build things like focus but also the capacity to notice the judgments that are going to pop up, like your brain saying, That sucks, you’re going to fail. The exercise is to come back to that again. It really is like if somebody goes for a run and says, Oh, that was exhausting, I don’t think I can do that again — they don’t get better at it. The exact same thing happens with writing.

I wonder whether creative writing programs could build this type of skill into their instruction and what it would look like.

We’d get a lot more novels. It’d be great.

All illustrations courtesy of Mark Freeman.