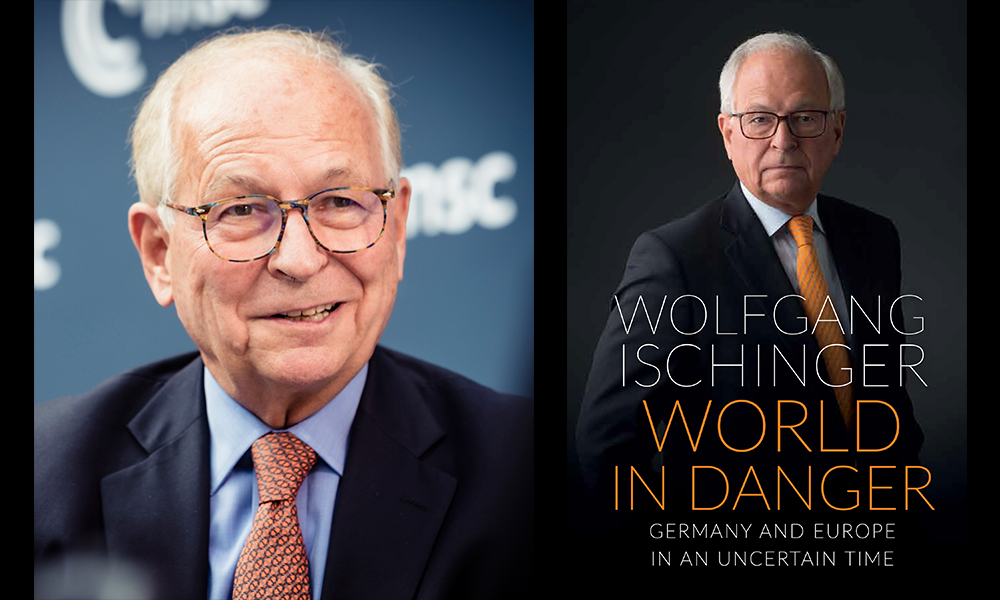

Which internal, institutional reforms will best help the European Union to become “a respected and capable global actor” on diplomatic and security concerns? Which distinct responsibilities should Germany pick up in that process? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Wolfgang Ischinger. This present conversation focuses on Ischinger’s book World in Danger: Germany and Europe in an Uncertain Time. Ischinger was Germany’s deputy foreign minister from 1998 to 2001, and has served as German ambassador to both the United States and the United Kingdom. He has chaired the Munich Security Conference, a leading forum for debating international security policy, since 2008.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with your “World Out of Joint” chapter, with its “five reasons why peace and stability are so hard to secure today”? First, could you sketch how the demise of unipolar US hegemony, alongside escalating frictions between liberal democracy and authoritarian state capitalism worldwide (and even within Europe itself), shape this book’s most basic call to reinvigorate effective European and transatlantic cooperation?

WOLFGANG ISCHINGER: I’ll start by taking one step back. In its original German version published in 2018, I wanted this book to explain to a German and European public that, contrary to what most people thought or perceived at the time, we were living through a period of dramatic change — with so much that we tended to take for granted unlikely to stay the same, even in the near future.

Here we could start with those concerns you just raised. Germans of my generation, born after World War Two’s end, have assumed for almost 70 years that our big friend the United States would forever offer military protection to an increasingly prosperous Europe. But today that foundational certainty has disappeared. That sense of certainty has been broken, not least by what Donald Trump has told European leaders, and told Europe itself for the past four years.

The second certainty my generation believed in was that Europe would remain on a stable course of continued increasing integration. The EU treaty offers the idea of an “ever closer union,” prospering together, unifying more and more. Of course Brexit, among other events, has blown away that vision.

A third certainty, shared across the Atlantic in recent decades, held that China (and presumably also Russia) would become, over time, what my friend Bob Zoellick described as “responsible stakeholders” in the liberal rules-based international system that we cherish so much — our system. We now see that the Chinese, for example, do want to participate in an international system, but not necessarily the one we proposed.

And for a fourth uncertain certainty, we in Europe and the US believed that our model of Western democracy, of human rights, of valuing the individual, would become the model that everybody else would rationally decide to embrace over time. But again that assumption does not look so certain anymore. We see authoritarian models of government, dictatorial models of government, populist and nationalist models of government emerging or fortifying themselves all over the place. So all of that led to this book’s basic point of departure, this sense that the world we thought we’d created seems to be collapsing, or out of joint.

From a German point of view, I see two central policy objectives of the highest priority. First, we need to regain momentum for building a more united and integrated Europe. Second, we need to reinvigorate the transatlantic relationship. Europe’s security has depended, does depend, and will continue to depend (whether we like it or not) on this transatlantic link, on NATO, on the American nuclear umbrella. The dream some Europeans express today about European autonomy in security and defense has no chance of becoming a reality for the foreseeable future. I share that nice dream, but I consider it absolutely, utterly, totally unrealistic for now. A responsible European political leader needs to rely on and to reinforce the transatlantic link.

You next list the “loss of trust on all sorts of levels” (stemming, say, from citizens’ declining faith in national governments and transnational institutions, from societies’ susceptibility to homegrown or hostile-power disinformation campaigns, from antagonistic nations sensing a corrosion in diplomatic communications) as a serious threat to peace and stability. On the broadest geopolitical level, could you outline some ways in which recent US government actions have contributed dangerously to this decline in global trust? How, for example, has US abandonment of the Iran nuclear deal, or the Paris climate accord, not just caused long-term harm to our transatlantic partnership, but undermined, in Chancellor Merkel’s terms, “trust in the international order”?

Let me put it this way. It makes a big difference whether South Korea or Estonia or Portugal keeps the promises they’ve made. Yet if they fail to keep their promises in international affairs, that regrettable fact typically doesn’t have huge geostrategic consequences. If the US, as the founder of the post-World War Two international system, begins to walk away from that system, and from agreements we thought we’d reached, and from NATO and transatlantic principles we thought we’d agreed upon for decades, that makes a fundamental difference. From my German or European perspective, I always have viewed the US not only as the creator, but also as the protector and guarantor of this rules-based international system’s functionality.

When the US, of all countries, abandons, opposes, and even sanctions the International Criminal Court in the Hague (which we’d established in part to make life more miserable for genocidal dictators), that doesn’t just raise diplomatic concerns. It damages and endangers this whole painstakingly constructed rules-based international system. It undercuts, as you suggested, our basic trust in this system — even as this system faces a whole new set of complex challenges.

The US has now created this doubt in our long-term alliances, and in our promises to each other. I’m speaking here specifically of President Trump raising questions about NATO. Do we need to support those wealthy Europeans, if they refuse to carry a bigger share of the burden? Do we need these commitments to collective security? I’m also speaking, as you say, of President Trump walking away from the Paris climate accord, and of course the JCPOA (the Iran nuclear deal). For the JCPOA, as you know, we started work back in 2003. Over 12 years, this initially German, French, and British project sought to find the best way to address Iran’s nuclear ambitions. After lengthy discussions that took years to complete, we greatly appreciated US willingness to join these efforts, and finally even take the lead during the Obama years, with John Kerry and Ernest Moniz playing crucial roles in making the JCPOA happen. Though then, in 2017, the US turned around and said: “Forget it. We’re walking away.” That, of course, raises fundamental questions of trust.

And quite frankly, Andy, this will transcend the Trump administration. This will leave, in the hearts and minds of US allies, the enduring questions of: So even if we reach this new agreement with the United States, how could we ever know for certain that the next American administration won’t just shoot it down? How reliable is this US partner? Would it be foolish of us to really trust the word of the United States? And look, as someone who has spent many years of my life in the United States, it does not make me at all happy to express these words. But honestly, this loss (or at least this apparent loss) of trustworthiness, of reliability, of staying the course, poses the single biggest challenge, now and in the years to come, for the kind of transatlantic partnership we need. Rebuilding that sense of unshakeable, automatic, mutual trust won’t come easy.

Then in terms of broader global forces knocking our world out of joint, a disturbing trend towards geopolitical brinksmanship stands out for diminishing the predictive powers of statecraft and diplomacy, and for making proactive conflict prevention (as well as strategic patience when conflicts do flare up) all the more difficult. What did the 2018 Munich Security Conference focus on brinksmanship reveal to you, for example, about our accelerating need both to reinforce institutional capacities for de-escalation, and to imagine new cooperative undertakings before we ever reach such crisis points?

Well again, to take one step back, a number of friends from America and Europe, people who had participated in the Munich Security Conference for a long time, got together and wrote pieces for a book we published in 2014, titled Towards Mutual Security. Seven years ago, the idea was: we’ve progressed in our management of the international system to a point at which we not only can trust our alliance partners, but can create a trusting relationship even with the Russian Federation (or certainly with a China that we assumed would become a responsible stakeholder).

Not very long ago, and not only for me in Munich, but among a wide range of international scholars and foreign-policy experts, this perception prevailed of the West having built a resilient global system based on rules that applied to all (and that all could accept), and on institutions strong enough to implement these rules. That idea, though, soon started to unravel. Of course we’d already had certain troubling incidents, such as Russia’s incursion into Georgia in 2008. But this idea of international progress really fell apart in 2014 with the events in Ukraine — with Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and with the conflict in Donbass that continues to this day. At the same time, the collective inability of the international community (including the UN Security Council) to stop an escalating genocidal war in Syria added in just terrible ways to a growing realization that instead of progressing, our international capacities to prevent or to resolve conflicts had actually declined.

We had begun drifting back to certain forms of geopolitical struggle we thought we’d left behind. We saw the renewal of arms races, especially in Asia. And we started seeing more countries and leaders make the calculation that they would not need to pay a serious price if they disregarded the rules, and pursued brinksmanship tactics, and tried to push things as far as they could, hopefully without taking us all off the cliff. Again, Russian behavior in Syria and Ukraine offers a case in point. But Turkey’s management of its foreign policy offers another — as do China’s recent threats regarding Taiwan, and its actions elsewhere.

Apparently it has become popular again, even among major countries, to threaten the use of force. When my book came out in Germany a couple years ago, some reviewers still asked: “Isn’t that title a bit too dramatic? A world in danger? Do you seriously mean that?” But I argued that this title wasn’t in fact dramatic enough. And since then, things only have gotten worse, especially due to this brinksmanship behavior, particularly on the part of great powers, unfortunately including the United States.

I should add here my distress at seeing no willingness on the part of the UN Security Council to fulfill its role as the sole institution that could offer legally binding solutions to all states, that could end hostilities, that could deploy a capable military force to prevent or to diffuse these kinds of conflicts. I see no willingness on the European and American side, and I certainly see no willingness by the other permanent members, to reform the UN Security Council and to let it actually do its job.

Returning then to Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territory, and now with a little distance from that once almost-unfathomable event, in what ways do you see it as a “wake-up call for European security”? How has it crystallized Europe’s need both for security from Russian invasion, and for a sustainable security architecture that includes Russian participation?

Here again we thought we’d built together a sturdy Euro-Atlantic security architecture that would provide a firm, enduring pillar of the international order. When had we done that? Way back in 1990, when all of our European member states, and all participants in what we then called the CSCE (the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe), got together at a summit and agreed on the Charter of Paris — which, among other topics, declared that Europe should have no changes to its national borders unless accepted by everybody, unless peacefully arranged, etcetera. And this basic idea that all CSCE participants would work from an agreed set of principles has tended to dominate our thinking (certainly German thinking) ever since 1990.

May I here remind American readers that we’re speaking, Andy, in October of 2020, precisely 30 years after Germany’s reunification on the third of October, 1990? We Germans (certainly my generation, but also younger generations) know well that, without massive support and trust and help from Washington (especially, in that moment, from President George H.W. Bush and people like Jim Baker on his team), we never would have achieved such a positive outcome. The German people will have eternal gratitude towards the United States for that. And on October third of 1990, the federal president of this newly unified Germany, Richard von Weizsäcker, said in his speech (and I quote from memory): “The Western border of the Soviet Union must not become the Eastern border of Europe.”

This obligation that Weizsäcker articulated in 1990 still plays an important part in German thinking. We’ve never abandoned this long-term idea of creating a comprehensive Euro-Atlantic security system. But we do need to recognize, as they say, that it takes two to tango. For the last decade or so, Russia has not agreed to play by mutually accepted rules. That probably has been the single most disappointing phenomenon for German foreign-policy makers since 1990, that failure to secure a sustainable, peaceful arrangement with the former Soviet Union, with Russia and our other Eastern neighbors. And in that case, we have to continue defending our own interests. But we shouldn’t give up.

We need to commit ourselves to increased defense spending, to strengthening both NATO’s deterrence and defensive capabilities — but while also keeping the door open to Russia. In German foreign policy we consider it crucial to let our Russian neighbors know that we have not closed the door. Russia can walk through this door at any time, but with one precondition: we all need to agree on and abide by the rules.

Your thoughtful suggestions for how to de-escalate and ultimately diffuse the Crimea crisis likewise made me wonder: what incentive does Putin have to back down from his current entrenched position? Where does Europe or NATO still possess leverage in this present case?

Given what I’ve seen in my own lifetime, I don’t think of anything in foreign policy or in international relations as categorically impossible. But you often need the right moment, with the necessary relationships of trust, and with fierce political willpower to get it done. And with today’s frozen or not-so-frozen conflicts (whether in Ukraine, or Nagorno-Karabakh with its recent fighting, or even with lingering unresolved tensions between Serbia and Kosovo), you still can of course resolve these issues. No law of nature prevents us from resolving them. But you do have to find the right time, and the right way that allows all sides to leave the negotiating table with no need to confess to a loss of face, or to a strategic failure.

In other words, can we in the West come up with anything to offer to the Russian leadership at this point, to bring about a Russian withdrawal from Crimea that benefits all sides? Quite frankly, I don’t see any realistic possibility at this time. At present, you don’t have much of the Russian public demanding that its leadership abandon this position in Crimea. On the contrary, the Russian public appears relatively happy about Crimea coming back into the national fold. So the moment does not feel right to me — which definitely does not mean it will never arrive. Maybe we’ll need to wait for a while. Maybe the Ukrainians will need to wait until Putin leaves office. This may take time, but that doesn’t make it impossible. We must continue supporting our Ukrainian friends in this quest, but we should advise strategic patience.

Specifically now for Europe, with momentum towards greater integration coming into question, you contrast the many ominous possibilities for a Europe plagued by internal divisions to the national, regional, and global benefits of a powerful EU speaking with one voice. So first, what would it look like for Europe to speak with a unified voice on diplomatic concerns, the way it does on trade? Which geopolitical challenges most necessitate that unified voice? Which institutional re-commitments and innovations can bring that voice into being?

The European Union’s 27 member states have agreed in our EU treaties (most recently, the so-called Treaty of Lisbon), that with regard to trade and many other matters, we’ll work on the basis of qualified majority voting. If a certain quorum of members vote for a decision, then it can go forward. You don’t need complete unanimity. By contrast, on questions of foreign policy and security (and certainly of defense), the treaty does demand unanimity. Every single member country has a veto right on every single issue. That leads to devastatingly negative perceptions of the European Union’s ability to speak with one voice.

I’ll give you a recent example. Most Europeans thought it necessary to express our collective dismay and shock at the behavior of the president and government of Belarus after the highly problematic election this summer. Most of us wanted to impose sanctions against the leadership in Belarus. But precisely one country, the small island nation of Cyprus, complicated this collective response. Cyprus didn’t have a direct problem with sanctions against Belarus. But nonetheless, Cyprus said: “We’re actually more interested in our own confrontational relationship with Turkey. We’ll only agree to sanctions against Belarus if all 26 others agree, at the same time, to sanctions against Turkey.” In foreign policy, we call this linkage politics. Cypress linked these two policy issues that had no real connection.

For weeks, we faced this collective inability to come to any decision. We sat there blocked. And that has happened with European Union foreign-policy decision-making over and over and over again. So we need to find some way to move beyond unanimity, to applying principles of majority voting, in our foreign policy. That’s a hard pill to swallow for some member states. And let me quote a Belgian foreign minister, Paul-Henri Spaak, who said some 30 years ago that “In Europe there are only two kinds of states: small states, and small states that have not yet understood that they are small.” Spaak’s statement applies just as well today. In a world where the US has 350 million people but also overwhelming soft power and economic power and military power, or with rising superpowers like China, and military powers like Russia, and India’s one billion people — these major players won’t listen to our small European Union countries unless we can devise effective ways to speak with one voice.

The European Union’s single biggest challenge today is to move beyond unanimity on foreign-policy topics. Chancellor Merkel, and Ursula von der Leyen (president of the EU commission), and the EU’s foreign minister, and numerous politicians from various European countries all have spoken in support of qualified majority voting. But supporting this institutional reform in a speech of course doesn’t necessarily mean putting it on the table in Brussels, and establishing it in practice. That will take real effort, and will also take time. Still I hope that in the next few months, we will see a first initiative undertaken (by Germany, with some partners) to move in this direction, and to make the European Union a more respected actor on global issues, an actor effectively defending our collective interests as a group of small nations bringing together 450 million people.

Specifically then for a Europe speaking with one powerful voice on questions of security, what makes a more robust commitment to defense spending (and to effective defense coordination) a critical part of any push for constructive relations both with current allies and with potential rivals? And even as you call on Europe to “become more operational…and continue developing into a defense union,” why does that not mean simply dropping the US as a foundational partner?

First, let’s once more be realistic. With the United Kingdom leaving the EU, 26 of 27 member countries (all except for France) have little possibility of defending themselves in a geostrategic world built around (again, whether we like it or not) the idea of nuclear deterrence and nuclear weapons. Even if we push for arms control, nuclear weapons won’t go away any time soon. On the contrary, we see additional countries trying to acquire them, and sometimes succeeding. Think of North Korea. Think of Iran and other cases. For European security, the transatlantic link through NATO and through bilateral arrangements with the United States will remain indispensable for the foreseeable future. I’ve participated in brainstorming sessions, trying to think through ways that the French nuclear force could cover all of Europe. We can discuss those very, very complex issues in academic circles. But in the real world, we still depend on the United States.

This means that, on the European side, we need to do our homework. We need to accept that the US has no obligation to offer us permanent military and nuclear protection, particularly if we don’t find ways to contribute that everybody sees as equitable and fair burden-sharing. So I totally subscribe to the idea that we in Europe need to demonstrate our commitments and our capabilities to take up a greater share of the responsibility, of the burden, for protecting the European continent through conventional military means.

One important element in building up our defense capacities involves pooling and sharing resources more strategically. Why do 27 small countries need 15 different types of tanks, or several different types of fighter aircraft? How can we more effectively combine and distribute our resources for air, land, and sea defense? How can we save money through joint procurement? How can we train our soldiers together? Answering those kinds of questions will undoubtedly make us stronger, and will also, as you say, make the European Union a more meaningful partner to the United States. That would in turn, I hope, strengthen the support that this transatlantic alliance enjoys — not only in Europe, but among American taxpayers and voters, whose backing remains essential for us.

Now specifically for Germany, how does Germany, perhaps most of all in Europe and in the world, benefit from a strong, sturdy, well-functioning EU and global free-trade system? And as Germany faces increased pressure to take on a greater share of global responsibilities, how would you hope to see your home country tack between the cartoonish extremes of “the fanatic democrat” (or pacifist, or moral purist) and the “political realist who has no problem with the suppression of others’ freedom as long as it keeps things calm in Western eyes”?

For Germany, this turning of an era (or “Zeitenwende,” as we call it in our recent Munich Security Report on German foreign and security policy) represents a great challenge. Hardly any other country has established itself so well in the liberal international order: politically, intellectually, militarily, but also economically. For one ecological analogy, for a long time, the liberal world order provided perfect habitat for this specialized species of the Federal Republic — which, as a civil power and trading state, had adapted perfectly to these conditions essentially guaranteed by others.

Now, with that habitat changing in numerous ways we’ve discussed today, Germany has to fundamentally rethink its foreign and security policy, and to accept that the old certainties will not return. This includes recognizing both that Germany has benefited more than average from the liberal order, and that it has been particularly hard hit by that order’s erosion. For a country so exceptionally well-integrated into the world economy, discussions of de-globalization or decoupling pose a fundamental threat to the business model.

So in my view, two developments will be crucial for Germany. First, we need new ideas and political leadership, especially regarding Germany’s role in the world. In recent years, expectations for our country have continued to grow. Over summer, a Gallup poll made headlines, for instance, by assessing the leadership provided by individual nations (including the USA, China, Russia, and Germany). Germany emerged as by far the most respected leader. To maintain that position, German political leadership now needs to step up to the plate.

My second point, however, is that this German leadership must contribute to building a stronger European Union. Germany must assume its role as an “enabling power,” as a “facilitator” for the EU. For the EU to become a respected and capable global actor, Germany’s commitment is indispensable. But the same applies the other way around. As I put it in the book, “For German foreign policy, one truth remains: Without Europe, everything is nothing.”

Finally, your concluding chapter mentions a “vicious cycle of panic and neglect that typically marks the global response to pandemics.” On which other topics (perhaps, for instance, perennial nuclear-proliferation concerns, or the diminishing effectiveness of antibiotic medications) do you see equivalent vicious cycles playing out? And in the face of these vicious cycles, what broader case might you make that when we don’t invest in persistently improving on effective global coordination, we end up paying the price anyway?

Today our collective security faces a diverse range of non-traditional risks. I address many of these in the book. Some have a link to health — such as the diminishing effectiveness of antibiotics, but also the mosquito’s expanding habitat resulting from global warming (which threatens proliferation of dangerous diseases such as dengue fever or malaria).

Climate change poses growing threats to international security through multiple mechanisms. A higher incidence of natural catastrophes, extreme meteorological events, and disruptive ecological changes (such as floods, droughts, and rising sea levels) will exacerbate political fragility and resource conflicts. Ethnic tensions, civil wars, and mass migration will emerge as consequences.

Technological change brings a broad range of further risks. In Germany, a woman recently died from treatment delays after hackers attacked hospital computers. That could be the first reported fatality from a cyberattack. And advances in artificial intelligence have particular potential to fundamentally change the global-security situation. To name only one important example: the future of armed conflict, potentially dominated by lethal autonomous-weapon systems, poses profound ethical dilemmas.

All of these threats share two fundamental aspects. First, they directly impact the individual, and have immediate consequences for personal freedom and security. But second, policymakers around the world need to recognize the importance of collectively addressing these security risks. Individual states, even those seen as great powers, cannot solve these challenges by themselves. Our foreign policy faces daunting tasks. But despite these challenges, I look optimistically to the future. I’ve learned how far persistent work can go in making things take a turn for the better.

Portrait of Wolfgang Ischinger by MSC/Kuhlmann.