How to decide when imitating/emulating (rather than interpreting, historicizing, critiquing) seems the most fitting response (for the moment at least) to a piece of writing? How to write critically about the artist/author whom, perhaps most of all, exemplifies New York School tendencies towards a conversational, collaborative, playful, serial, constraint-based focus on the daily, on friendship and exchange, on the personal/private versus the public/professional? How then, much more specifically, to reconfigure Joe Brainard’s fabled “I Remember” structure when somebody asks you for an academic essay? Andrew Epstein and I posed these questions to each other when Yasmine Shamma requested we respond to the essays she has gathered for her forthcoming Edinburgh University Press collection, provisionally titled Joe Brainard’s Art. Preceding talks with both Epstein and Shamma hopefully can help to show why I consider this current piece part of a lively, ongoing conversation.

¤

I wonder about everybody writing about Joe Brainard at one point calling him “Joe,” and now they don’t anymore. I wonder how Joe Brainard would’ve felt wondering whether to call someone he’d never met “Joe.” I wonder what room remains in critical work to mourn this passing of “Joe” (which that work itself perhaps brought about), or I wonder if/what John Ashbery, before he himself died, ever would’ve thought about anything like this. I’m thinking (to bring this back to Joe Brainard) about thoughts that never reach articulation, or more importantly, what to make with them. I wonder, basically, what we’re starting the day after Valentine’s…

I wonder if there is any way around this very Brainard-specific paradox: how can we think and write critically about an artist who was so resolutely against monumentality, formality, professionalism, careerism, and academic protocols and high seriousness. Wordsworth says “our meddling intellect / Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things: — / We murder to dissect.” Can one write about Brainard’s work without doing violence to what makes it so fresh and enduring, strange and inimitable, in the first place?

I wonder also about Joe Brainard’s mode of loving his audience a bit less (or just less desperately) than most, why that attracts us (especially some of “us”) so much, or how his poetics collapse so fast when they do start pandering. Or Ron Padgett’s reflective treatment in “Joe Brainard’s Boom” gets me wondering about niceness as (in part) a shy person’s negotiation (internal, external) of violence. Or Rona Cran’s “Men with Pair of Scissors” piece makes me reimagine collage-making after dinner (stoned) at Kenward Elmslie’s Vermont place as its own small-scale utopian (so more internally fraught than it appears) negotiation of violence still not long after Stonewall. Or Alice Notley’s line “I know I have to mention the fact that he intended for his collages to fall apart” seems a nexus of so many violences. So even with our meddling intellect sometimes rhyming “murder” and “dissect,” I’ll sense Joe Brainard beckoning us to wonder forwards about say those dinners at Kenward’s, about the Padgetts sometimes being there, about if/when/why queers + straights commingling = queer.

I wonder if we can relate the stance you just identified — one based on diffidence, shyness, on not caring too much, all as a reflex to violent threat — to that signature Brainard tonality, which appears to be insouciant, childlike, and innocent but is also at some level a calculated effect, a move in a (deadly serious) game. I wonder if we have adequately defined faux naiveté as an aesthetic position or stylistic choice. I wonder why people, including me, love it so much, finding that tone or outlook appealing and fun, pleasurable and fresh. I wonder if we (as critics, as readers) have identified and theorized, with enough precision and depth, faux naiveté as a mode driving a great deal of wonderful writing, art, music, and so on. It stands at the very heart of Joe Brainard’s work and also feels central to so many others, from Gertrude Stein to Jean Dubuffet to Andy Warhol, Kenneth Koch and Ron Padgett to Lydia Davis. I wonder what makes it so attractive and enduring — whether it has something to do with the powerful tug of childhood, a longing for lost simplicity, a return to more innocent ways of writing and thinking and viewing the world. I also wonder if it is sometimes, or always, a pose — a performance of not-knowing, where one pretends to be less sophisticated than one actually is. I don’t know whether it is a problem if that is true, or if it makes this stance less attractive, or maybe, somehow, more.

I wonder if all this wondering that you and I are doing is an echo of Brainard-esque negative capability — the not-knowing-for-sure which runs so delightfully through Brainard’s work. In that sense, perhaps our project is trying to put into critical practice what Brian Glavey identifies as Brainard’s fascination with “tact,” after Roland Barthes — a form of “queer neutrality that quietly opts out of binary oppositions rather than trying to undo them,” refusing reduction, fleeing dogmatism. I wonder if our wondering about Brainard — rather than answering, mastering, or defining — is commensurate with this element of his oeuvre. I’d like to think so. But I also can’t escape the question of the previous paragraph, and do wonder if what we’re doing is also, at the same time, a performance or pose of naiveté.

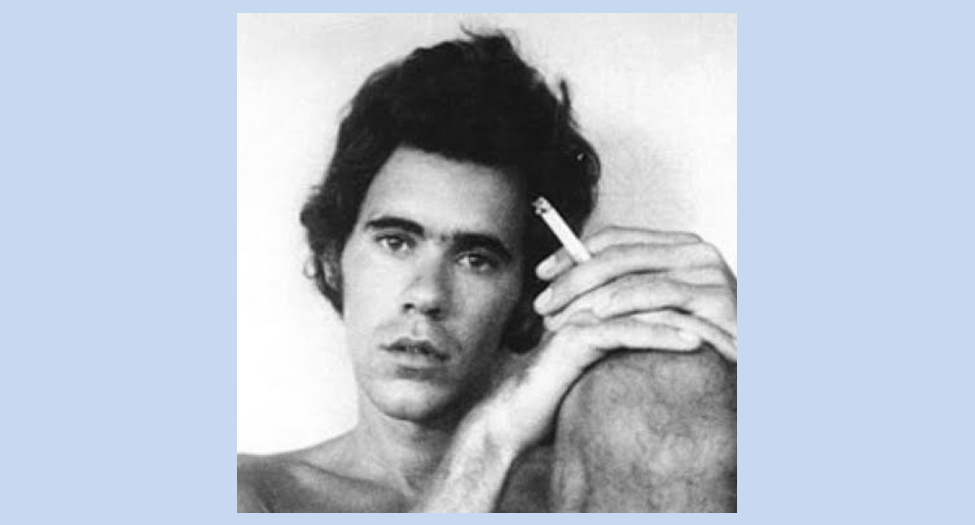

I wonder about posing mostly for yourself. I wonder about proactive posing. I wonder which of us still theorize sociability mostly when alone. I wonder of course about Joe Brainard smoking. I wonder about Joe Brainard, and then a particular critical community, sniffing out the bottom nature of every single cigarette butt. I sense possibilities for friendship. I’ll wonder, while people theorize Joe Brainard’s affect-laden touch, why we often pretend Andy Warhol has no affect. I wonder about Andy Warhol still never having friends. I wonder, “following” Nathan Kernan: if Felix González-Torres queers Minimalist prototypes, if Joe Brainard queers Conceptual art, then, again, what we’re doing (should do). I wonder if Joe Brainard liked “West End Girls” (still no real feel for that specific moment in New York — with no neighbors in my distant suburb dying). I wonder (“following” Jess Cotton now) about looking to criticism like looking for intimacy. I wonder about criticism conceived of as where two “bodies” touch. I also of course wonder about Morrissey’s “Please keep me in mind.”

I wonder too how much of successful theorizing, successful criticism, concerns cuteness, cute concepts, cute titles before the colon. I’ll always appreciate Wayne Koestenbaum letting me know scholarly prose could feel more sexy. I hope Jess Cotton, Rona Cran, Brian Glavey don’t mind me mentioning their name is cute. I get nervous when Jess Cotton quotes Joe Brainard’s banana-peel joke (too cutesy for me). I wonder about my particular prudery once wishing Joe Brainard never had tested these limits and gone cutesy. I remember now all the (cool, smart) poets and scholars telling me it would be too cute to write about Joe Brainard. I also wonder, “following” Jess Cotton, about causality (sorry) as “a still life as a series or a series that it is in the process of becoming still life.” I wonder about all the cute typos scholars cut (straying here to Rona Cran: “suggesting that mistakes or inconsistencies were best understood as evidence of progress and creative growth”). Or I’ll wonder how many of us fantasize turning critical typos into a “creative” project. Finally, Jess, I’d love to work together sometime on transforming feminized fetishized representations of powerlessness into vital passivity (hopefully this will include some drawings).

“I wonder just how much other people think the things I think,” Joe Brainard writes in “Diary 1969.” “I wonder / if Jan or Helen or Babe ever think about me,” Ted Berrigan writes in “Personal Poem #2.” “I / wonder if Dave Bearden still dislikes me. I wonder / if people talk about me secretly. I wonder if / I’m too old. I wonder if I’m fooling myself / about pills. I wonder what’s in the icebox. / I wonder if Ron or Pat bought any toilet paper this morning.” Frank O’Hara closes “Personal Poem” by writing: “I wonder if one person out of the 8,000,000 is / thinking of me as I shake hands with LeRoi / and buy a strap for my wristwatch and go / back to work happy at the thought possibly so.” In “Flowers,” Alice Notley writes “I wonder if this is an obnoxious poem / I wonder if it’s really understood that / Poetry and I are its subject.” At the end of his gut-wrenching poem “The Circus,” which is about memories of writing another poem twenty years earlier that was also called “The Circus,” Kenneth Koch writes “And this is not as good a poem as The Circus / And I wonder if any good will come of either of them all the same.” “I wonder how much longer I can keep writing poems and pretend not to be a poet,” Joe Brainard writes in “December 22, 1970.” At one point in Midwinter Day, Bernadette Mayer writes “I wonder why we write at all.”

I wonder why nobody here points out John Ashbery’s (lovely) collages being a billion times flatter. I feel this least with 1972”s Diffusion of Knowledge. I wonder what advice Joe Brainard gave on that. I do appreciate, in 2008’s Chutes and Ladders, the central pansy-head’s James Schuyler sailor’s-basketed salute (The Checkered Game of Life gives a boy scout). I do appreciate how the numbers really “break down” in Popeye Steps Out. I do wonder (letting out the dogs now, crunching last night’s pawprints from this rented Colorado backyard), when you read about Joe Brainard, which lines make you (make everyone) feel your shy, humble, handmade side (for me, from Brian Glavey: “Having never learned to type, Brainard composed the work longhand and then meticulously copied out each new revision in his distinctive block-capital script”). Or I do wonder, when Jess Cotton presents Joe Brainard always as an artist-poet, his work inherently juxtapositional, desiring relation, drawing closer to its object, to its subject, to us, with all involved discovering new perspectives on themselves within this moment of composition…Or I do wonder, with Jess Cotton sounding so smart, whether she also has a haptic relation to the word “haptic.” Or then even with Joe Brainard’s “Dear John” letters: “Then too, most of what I have seems to have more to do with the color and texture and character of paper as opposed to imagery…”

I wonder if there is an inherent link between the ethos of the New York School, broadly understood, and the act (or pose) of wondering — as John Ashbery says, “for this is action, this not being sure.” It is not like we have much choice in the matter. As Gertrude Stein writes “She would not wonder if this were not thunder it should not thunder and she would not wonder. She would not wonder if this were not thunder.” But thunder it does. I wonder if the fact that spring is already here and not there will affect (or infect) the mood and shape of our paragraphs, our parallel graphs. I wonder if the joy of juxtaposition, the sheer delight and haptic pleasure of weaving disparate things together (recalling the root of texture), which seems to be at the heart of Brainard’s collage aesthetic — if not all collage — can be thought of as just another example, alongside wonder, of what Frank O’Hara calls (speaking of the sun) a “nebulous / healthy reaction to our native dark,” acknowledging the bleakness of our innate condition. For all his sunniness and good cheer, Brainard knows exactly how dark things really are.

“I wonder” also appears in A Fish Called Wanda. “I wonder” of course sounds more like wandering when Del Shannon slips in “wah wah wah wah.” “I Wonder U” by Prince (probably my favorite) just goes:

I, how you say, I wonder you, I wonder you

I, how you say, I wonder you, I wonder you

I, dream of you, for all time, for all time

Though, you are far, I wonder you, you’re on the mind

I wonder if Joe Brainard’s “lifeworld” could include that song.

I wonder “with” Nick Sturm about our own devotional labors, about care, anxious self-flagellation, about sharing pleasures of one who works against work (who generates literature as a byproduct to one’s resistance to labor), and also “with” Nick Sturm about experiential time-management, about putting off the work (sometimes the work of thinking?) to produce the work, and then also about “I should do this / I should do that,” and all framed (how lovely) to look like a photograph. But then I also wonder about Joe Brainard at one point really stopping, then also about Joe Brainard’s relationship to all the people who really do “nothing.” But later I’ll relax a bit when Timothy Keane introduces Ray Johnson’s “nothings,” though then just as I settle into stably identified critical reading again: “Years later, Johnson’s untimely death following a wintertime leap off the Long Island Bridge…” I also do still wonder about had we stuck to our original plan of getting high to write this or just to talk, like Joe Brainard probably would. I wonder about all those edibles (gummies) hard in a shed back home right now.

I wonder too, after reading Nick Sturm on Brainard’s ambivalence about labor, whether what we are doing here “counts” as “work.” I wonder whether our collaboration is a by-product of a “Bartleby-esque refusal” to work in the conventional sense, and if Brainard would nod and “get it.” I wonder whether writers and artists and scholars often find it hard to draw a bright line between work and pleasure. Different kinds of work are still work. Collaboration can be fun but, as Emerson says, “conversation is an evanescent relation, no more.” I wonder why I never noticed that the word collaboration contains the word labor. “Collaborating on the spot is hard. Like pulling teeth,” Brainard wrote in a diary. “There are sacrifices to be made. And really ‘getting together’ only happens for a moment or so. If one is lucky. There is a lot of push and pull. Perhaps what is interesting about collaborating is simply the act of trying to collaborate. The tension. The tension of trying.”

I wonder about the pantheon of adjectives used in so many enlightening discussions of Brainard — modest, small, minor, quiet, tiny, miniature. We hear about his “esthetic of smallness,” his “air of unimportance.” The title of the People magazine feature on Brainard that appeared at perhaps the peak of his modest fame? “Think Tiny, Says Joe Brainard — And a Show of 1,000 Miniatures is the Result.” I wonder if Brainard’s smallness can, or should, be re-framed as a strength, as amounting, paradoxically, to a bigness. Paul Auster writes of I Remember: Brainard “begins and ends small, but the cumulative force of so many small, exquisitely rendered observations turns his book into something great.” I wonder if devotion to the small can also be a philosophical and political position of great power. I wonder if Brainard would have felt kinship with this passage by William James: “I am against bigness and greatness in all their forms…. The bigger the unit you deal with, the hollower, the more brutal, the more mendacious is the life displayed. So I am against all big organizations as such, national ones first and foremost; against all big successes and big results; and in favor of the eternal forces of truth which always work in the individual and immediately unsuccessful way, under-dogs always, till history comes, after they are long dead, and puts them on top.” I can imagine Brainard digging this sentiment, though I suspect he might’ve recoiled from “the eternal forces of truth” and shied away from James’s celebration of the beleaguered little guy’s triumph at the end. But maybe what we are seeing now is history putting Brainard the underdog, long dead, on top anyway.

I wonder again here about Claes Oldenburg’s:

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top…

I am for an art that a kid licks after peeling away the wrapper…

I am for an art that coils and grunts like a wrestler.

I wonder still (coiling back to Anna Smaill) why I ever got so hung up on people prioritizing Joe Brainard’s niceness. But I’ll also still wonder what present-day poetries as structurally sophisticated as I Remember could look like. I also wonder when I ever started talking about “rigor,” but also almost always remember wishing conversations could contain a bit more. I’ve felt forthcoming eclipsing shame for several straight days opening this essay collection, desperately disassociated (for years, probably) from anything I’d ever written in a “critical” vein. I wonder which writers I’d like better if I knew they felt that way. I’ll sense strong shameful relief seeing people I admire (people we all depended on to write this book) getting trashed for the moment instead of me. I often wonder how Marjorie Perloff feels. I’ll wonder about Joe Brainard, in a parallel universe, teaching some nighttime college class called “Non-Oedipal Criticism.” I feel such strong relief knowing I’ll call Chris Schmidt after reading today. I remember (really) discussing dissertations late one night at a diner after a restaurant closed. I wonder why he’s not (no I wish he was) in here. And I really wish for none of this to come across as “against” Anna Smaill. I’m touched anyone still finds value in a white male poet writing “I have nothing that I know of in particular to say, but I hope that, through trying to be honest and open, I will ‘find’ something to say.” I could see all of “I wonder” coming out of that. And I wonder, finally, if the offer I put on a house today will get accepted. I wonder if everybody’s broker always says in advance: “There’s no way this offer is going to get accepted.”

I wonder whether Brainard’s obsessions with habits and pursuits now universally viewed as very unhealthy, if not deadly — extreme sunbathing and cigarette smoking — date him as a figure of the 1960s and 1970s as much as the aesthetic choices he makes in his art and writing. I remember how big a deal it was to “lay out” and “get a tan” in high school. I wonder about the precise moment that practice finally died. John Ashbery titled one of his late books Where Shall I Wander, which makes me think of “I Wonder as I Wander” and Del Shannon and the closeness of those two crucial words. I wonder why the crooked way can never be made straight, why so much that’s offered is not accepted, why no pleasure is pure, why Brainard wrote things like “life can get pretty scary if you don’t watch out,” but so many still tend to think of him as a “happy,” “nice” “saint.” I wonder about those qualities Ron Padgett says his own “perennial optimism” caused him to once overlook in his friend — “the seriousness of the downs,” the “gravity of some of Joe’s bouts of insecurity, uncertainty, and despondency.” I know Brainard claimed he “wasn’t very political” and “never felt very strongly about a cause” (“if I don’t like something I just tend to ignore it”), but I wonder what he would have thought, or done, about high school kids getting slaughtered, again, in their school by yet another semi-automatic rifle. I wonder what to do with all we ignore, yes, but also what we cannot ignore. I wonder why, on such an utterly perfect spring day, these March mosquitoes have to already be such a flitting, prickling nuisance.

I wonder (circling now to Kimberly Lamm’s smart piece) who actually experiences “standard temporalities of sexual development in which the sexuality of the adult is wholly distinct from that of the child.” I wonder if, as someone pretty straight, I can discuss the huge embodied relief I first felt encountering Joe Brainard’s “possibility of an aesthetic practice that gives queer desire access to the normal.” Or if “Nancy’s decidedly normal, slightly dykey, always-perky girlishness undermines the hyper heterosexual masculinity that subtends avant-garde aesthetic practices of the late 20th century,” I wonder what Joe Brainard’s gayness helped restore in me. I wonder sometimes, collaborating with men friends, about the “endless possibilities” this opens up, but then how much I also need to collaborate with my women friends. I wonder about all the different productive crushes. I wonder, thanks to your “laying out” memories (primal scene, of course, for I Remember, with baby oil) about this happy-looking tan cow a girl hugs on my Organic Valley milk carton. But I’d also love, more critically, to see some intensely philosophical speculation starting from the jackoff collages.

I wonder if we can extend what Lamm calls Brainard’s “queer poetics of the normal” to his distinctive version of everyday-life aesthetics — that long lineage of quotidian poetics which stretches from, say, Whitman and Baudelaire to Williams and Joyce to Beckett and O’Hara and beyond: how he not only makes queer sexuality normal, but also queers the everyday, the average, the ordinary, the boring, the normal. It seems so perfect that Brainard taught a course called “Elusive Realism.” Reading work by and about Brainard, I wonder if I should be collecting and salvaging more of the flotsam and jetsam, the everyday crap, of my own passing days. I wonder what forms those acts of collecting can or should take. “Brainard is a born diarist,” a New York Times review of his work once observed. “No moment of the day is dead to him.”

I wonder again about the gains and costs of devising a critical approach that’s well-suited to the object of study, attuned to its peculiarities, commensurate with its rhythms, its textures, its weirdness. I remember a professor in college half-joking, half-criticizing an essay I wrote on Absalom! Absalom! because it seemed to mirror its subject, with unusually long, convoluted Faulkneresque sentences. I didn’t realize I had done this, but was kind of proud to learn I had. I think of how my mother used to shift her voice when speaking on the phone with different people, unconsciously mimicking accents on the other end of the line. As Paul Auster writes, in I Remember “the memories keep coming at us, relentlessly and without pause, one after the other with no strictures regarding chronology or place.” I worry about why the annual azalea explosion is happening so early here this year, wonder how long it will last this time. In class today, it seemed more moving than ever when we spoke of how James Schuyler tries to capture an everyday moment only to find it always slipping away as it is happening, as he describes it. After his big show of stunning flower paintings, Brainard confided in his diary that “I’m not really that interested in gardens anymore.”

I wonder, along similar lines, what else you work on each day right now. I wonder how our wondering seeps into those projects. For me, for this week, for Rachel Galvin:

I wonder when adynaton (here with “Esthétique du mal’s” serialized, asymptotic, kaleidoscopically structured adynaton perhaps the most elaborate case) needs to fail at first, needs to evade possibilities not only for first-degree but also second-degree charismatic poetic authority, and how/when wartime temporalities might discourage or encourage such a project.

For Reverend Liz Theoharis:

I’ll admit your claim that “God hates poverty” left me wondering why, then, most species, humans included, probably have faced conditions of scarcity akin to poverty throughout life’s history (but I get that your book also makes theological moves I don’t fully grasp — here, for instance, reframing poverty not as some supposed individual sin or problem, but as society’s systemic sin or problem).

For Bhanu Kapil:

I think both my question and your response began by wondering how discharge might become possible through site-specific engagements both in India and the U.S. At some point Ban does declare it a “mistake” to perform, let’s say, one’s critique of the British far-right to a California audience — but then one notebook entry articulates the value in writing about England far from England, in approaching Englishness as this thing that decays, and watching it decay.

For Michael Hardt:

Well under the sign of “experiential joy,” I wonder if we could tap one of its more SM veins — perhaps by bringing in your preceding investigations of how power, even as it seeks to colonize subjectivities, might end up prompting previously untapped “constellations of resistance and refusals to submit to command.” So here could you sketch a historically specific scene in which, “as our past collective intelligence is concretized in digital algorithms, intelligent machines become essential parts of our bodies and minds to compose machinic assemblage”?

I wonder, still in terms of labor, not how much money Kenward gave Joe Brainard, but when in life various individuals would have to get the money in order for it to help them get their work done. I wonder when an “oddball” getting rich just makes that person more private. I wonder, more publicly, whether Kenward and James Merrill felt made from the start. I wonder about Joe Brainard’s “bodhisattva days” crossing Great Gatsby with Fox and His Friends (both also concluding on a young man’s body). I wonder no doubt most of all what precisely the dogs think before running upstairs to scratch then settle then “study” with me for a few hours. I wonder who else feels extra rich because of dogs (so muddy with the thaw today). I’ve even caught myself wondering whether they would have been friends with Whippoorwill.

I wonder, again, about labor and pleasure, and if there is something “slightly unprofessional” about this project we’re doing and whether that is “the best thing about it,” to quote something Brainard said about his own work. Rona Cran quotes that phrase as she explains Brainard’s impatience with “visual perfection” and mastery, his affection for the rough and ragged pleasures of error and accident, jagged contours and lack of polish. Brainard actually said that sort of thing pretty often: for example, about his (wonderful) cover for the Anthology of New York Poets, edited by Brainard’s friends Ron Padgett and David Shapiro in 1970:

It is a white cover with red words and objects. Floating objects…. Somewhat by accident, I have broken every rule of good design. (Which pleases me). This happened, I think, because I did the cover very slowly. Object by object. Over a period of five or six days. With no (or little) finished project in mind. One object or one word told me where the next object or word would go. Allowing little room for “dash” or “inspiration.” The result is clean and unprofessional in a good way. And cheerful.

One object I deeply love is the old copy of that same anthology which David Shapiro signed and handed to me just after I defended my dissertation, that day so long ago. I like hearing that Brainard seems to be spreading into the rest of your work, your life, these days too. Whippoorwill, the white whippet, would likely have loved your dogs; Brainard writes that “Whippoorwill is stretched out on the grass to the left of my feet. In his own way I suppose he is sunbathing too. He does seem to love it.” I wonder how to categorize this slow-motion game of ping-pong, our slowly sending these paragraphs, these “floating objects,” back and forth, west to east and back again, and (slightly less) why I feel the need to.

I wonder though if I mentioned skipping “AWP” in Tampa, flying instead to Miami, basically sprinting now to the Institute of Contemporary Art (past somebody’s discarded velcro wallet, trampled tangerine peels) for 35 minutes before my in-laws arrive for our Little Havana tour celebrating their 50th anniversary, because my father-in-law’s parents went to the real Havana for their own honeymoon (because Donald Trump cancelled our plans taking them to real Havana). I wonder, amid all this shattered (nothing scary about it) Midtown glass, if I’ve mentioned ongoing vision problems getting much worse now, though now appreciating scent (I mean active sense, not passive smell) restored with warmth, just before first raindrops. I wonder for how long all cool U.S. sneaker culture probably has come from Miami. I wonder also, now on the jog back, about a Port-au-Prince-based painter I really admire claiming to dismantle the “Western subject,” and about 60s artists (OK, Hélio Oiticica’s seashells, a bit before Joe Brainard’s) living out that subject, and who went farther.

I wonder if it’s time to build a canon of writers and artists who like things, who are enthusiasts, and flesh out what they share. Some critics, like Brian Glavey here and Jonathan Flatley in his new book, have helped us begin thinking critically about liking as an aesthetic stance, an affective mode. I like David Herd’s very interesting book on the subject, Enthusiast!, and especially like that apt exclamation point in the title. Brainard went so far as to define art as “a way of showing my appreciation of things I like.” In the early 60s Brainard also wrote two poems called “I Like” and a fascinating, prescient early prose piece on Andy Warhol (around 1963) that seems to understand things about Warhol’s aesthetic of liking, and his obsession with repetition, way ahead of the art historians and critics. In “Andy Warhol: Andy Do It,” Brainard writes “I sure do like the way his ideas look. Andy Warhol’s ideas look great! Andy Warhol paints Andy Warhols. And I like that. I like Andy Warhol. I like Andy Warhol. I like Andy Warhol. I like Andy Warhol. I like Andy Warhol,” and so on for many lines, and then writes “I find Andy Warhols to be spectacular, grand, clean, courageous, great to look at, and likeable. I like Andy Warhol. And there is more to be said. I like Andy Warhol.” I wonder if the Warhol critical industry has taken note of Brainard’s piece, though I doubt it. I like writing this while looking out at the white sand and waves of the Gulf of Mexico. Yesterday, I listened to some recordings of Brainard reading his work and watched recent footage of some famous friends and fans reading his writing: people like Paul Auster, Frank Bidart, Harry Mathews, Ron Padgett. I wrote in a notebook “Realizing that I like listening to Joe Brainard read and I like listening to people read Joe Brainard.” I like Miami and institutes of contemporary art but don’t like at all hearing about your vision problems. Brainard wrote in a diary: “If I have anything to ‘say’ tonight (a bit drunk) it is probably just this: to like all you can when you can.” I wonder what this conversation would be like if we’d chosen “I like” instead of “I wonder” as our constraint.

I wonder about Florida residents yourselves vacationing “down at the Gulf of Mexico.” I wonder if a copy of The Vermont Notebook exists on Marco Island. I wonder if John Ashbery and Joe Brainard ever knew or loved anybody on Marco (they mock its “developers’” no-doubt delusional or cynical or sinister eco-friendly claims) like I do. I wonder if they ever would have gotten the one other person I know who has lived on Marco, who sold Avon products here, in the mid-60s I imagine, before his academic career. Or with the Gulf basically Florida’s Midwest, I wonder what only Midwestern people get about Joe Brainard (and I can wonder, if you want me to, whether the opposite is also true). I wonder about “Vermont” as Joe Brainard’s place to pass. Or I’ll wonder about the two draw-ers, Andy Warhol, Joe Brainard, perhaps once discussing the Midwest (seated someplace loud, somebody feeling lost, on drugs or something). Or I get to Brian Glavey’s “does not in the end treat the text as a person; instead he treats the person as a text.” I’ve reached friendliness as “an aesthetic category.” I have arrived at “gentleness, sweetness, tact,” as “not essences but effects.” I pause on “goofball wasteland.” I wonder about creating social-network space to disappear within, to deflect attention from his own self as a way of mediating other people’s anxieties and embarrassment. I wonder about Joe Brainard, about Brian Glavey, about you of course celebrating the ordinary without rendering it extraordinary or uninteresting. He starts describing Women’s Household as a forum for channeling powerfully queer identifications and desires. He keeps reaching towards the (potentially normative, but repressed) queer feelings that do exist within the ordinary, the (potentially poignant, but progressively repressed) deeply ambivalent desire for normativity itself. He states then that to imagine, still in Stonewall’s summer, everyone as queer, presents a pointed and moving feat of imagination. He makes me wonder, when we encounter the “I remember” phrase, how much we prepare for our mom (a loaded reference point for sure) to tell us something ancient about ourselves. He makes me wonder whether criticism ever could remember in a mother tongue. He makes me wonder whether criticism ever can shyly just look away. He makes me wonder why, when I had the chance, I never took one of Eve’s classes. I glance down at my Brian Glavey notes one last time and think I spot the word “cupcake.”

I wonder why “goofball wasteland” seems like it would be a particularly apt description of Florida, if not America. Just now taking a walk on the chilly beach, when I should’ve been writing this, I thought of Nick Sturm discussing that moment where Brainard weighs whether to work on art versus going to the beach in Bolinas with Bill Berkson (“Bill just called. It’s the beach for me. Fuck work”). I wonder now, with a twinge of regret, whether I should have found more room for Brainard in my study of the aesthetics of everyday life, since it becomes clearer to me each day how well his own brand of elusive realism, his tireless, joyous methods of queering the everyday, fits in with the mode I explored there. Like others I discuss (A. R. Ammons, Bernadette Mayer, James Schuyler), he loves fashioning experiments and projects of attention driven by self-imposed constraints. “A lot of times,” he said, “I set up something for me to do. Like I’ll say ‘I’m going to paint a peach’…or if I’m writing I’ll say ‘I’m going to sit outside and describe what’s around me’, or ‘I’ll try to write very short stories’, or some kind of project. And that was a project.” I wonder (still) about the magnetic pull of projects. After a student of mine, a poet, told me she’s memorizing poems, one at a time, I’ve spent the last week trying to memorize Wallace Stevens’s moving late poem “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” for small reason, each day getting a couple lines down. I’m still wondering what you meant, weeks ago now, about how Brainard’s poetics collapse quickly when they start pandering. In one of his everyday-life projects, “Wednesday, July 7th, 1971,” Brainard spends an entire bus trip to Vermont writing in a notebook (surprisingly reminiscent of what Ron Silliman would do a few years later on the Bay Area subway in his prose poem “BART”). Wondering, Brainard writes “I don’t wonder why I’m telling you all of this. I wonder if you’re wondering why I’m telling you all of this. (?)”

I wonder then what it would take to discuss my real-life big question from this week, which concerns my “digestive system” in Florida. Though I do wonder what all this pesticide does to Marco’s little lizards. I do wonder why the sea has felt so “foul” the last couple trips (with red tide of course just the most immediate, innocuous, vacation-reinforcing even while complaining response). Or in terms of what Joe Brainard wondered from the Vermont bus, I did finally, that last morning in Miami, while everyone packed (always packing the night before), understand “second-order” philosophy as no diminishment (no diminutive, really). That probably helps explain hating “wonder” as a noun.

I wonder what makes Brainard’s attempts at radical honesty and inclusivity in his writing so arresting, innovative, and complicated. I wonder about all that we’ve managed to include in this conversation and even more so about how much (nearly everything) that we’ve also left out. I wonder what the critical or scholarly equivalent for “TMI” would be. To be honest, this weird and wonderful month-long immersion in the world of Brainard has left me with a deeper sense of awe at his not-actually-“modest”-at-all achievement, and a bit mad at myself for not fully recognizing it before. I wonder if we could count on one hand other figures as distinctive, as gifted, as interesting, as important in both visual art and writing as Joe Brainard is. I wonder, after all this wondering, what makes Brainard’s fierce and loving attention to the ordinary sui generis, so moving, so delightful. When Ashbery wrote about Brainard’s ravishing flower paintings, he too was left wondering: “The effect is always of profusion and of strangeness beyond that. What is a flower, one begins to wonder? A beautiful, living thing that at first seems to promise meaning…but remains meaningless…. Here they merely continue, each as beautiful as the others, but only beautiful, with nothing behind it, and yet…”

I wonder (here recalling John Ashbery’s description of Joe Brainard’s works as “about themselves — their subjects — and the distance between him and them is also a subject, whose nature is self-narration”) about self-narration as always approaching death, as perhaps resisting but nonetheless rehearsing death. I’ll wonder about dead people forever retelling themselves about themselves (as still a far too dramatic description of death). I’ll wonder, personally approaching Joe Brainard’s pansies, about “easeful Death,” side by side filling the field (as in life). I’ll wonder (perhaps especially flying home, biting into an apple’s bruise) why death doesn’t directly shape more people’s basic value standards (or just how/why we ever would apply the term “success” to somebody still living). Or just from Timothy Keane’s second section:

I’ll wonder why I consider prose recording “wish-fulfillment fantasies, psychological projections on to other people, frequent unspoken asides and non-sequiturs and accounts of how the passage of time and the willful ego are suspended during art-making” perfectly normal

I’ll wonder if I’ve been better off not knowing (until now) about “the anti-memoir”

I’ll love though: “truant behaviors that take precedence over the fact-finding and historicizing responsibilities of traditional autobiography”

I’ll love the fragmented: “these nonlinear, open-ended playtime normally restricted to childhood”

I’ll always really love: “‘My body is free of its image-repertoire,’ writes Barthes about the photographs, ‘only when it establishes its work space.’”

I cannot help loving: “self-embarrassment through a discourse around spontaneity and impulsiveness”

Of course I’ll love questions: “Are the itemized one-way ticket and…incongruous cut-out about an assassinated leader hinting at a kind of self-erasure or suicide?”

I’ll just love Joe Brainard’s prose: “‘A lot of being inside your own head here [in Bolinas],” he writes, “A lot of talk about it. And a lot of talk about inside other people’s heads too’”)

Of course I’ll just love feeling you can face death “from the first-person to other individuals and back to…first-person in a loop that leaves nothing resolved…within such half-completed dialogues, cross-cut angles, tentative observations, sudden reversals and philosophical aporia”

But mostly I just love Joe Brainard (the real person, I think), from the backseat, feeling “abstractly sad and alone,” still holding Bobbie Creeley’s hand. I wonder about his lost “‘baroque pearl and emerald pendant from the Italian renaissance’” maybe still in the sea off Bolinas.

I wonder how it can suddenly be mid-March, past the ides already, the day for amateur drunks to wear green and cause havoc in college towns and city streets. I wonder why I feel anxious about having the last word in this exchange, this evanescent relation, which feels like it shouldn’t really come to a close. I went into this not feeling terribly worried about the question that seems to nag so many Brainardiacs — why he stopped writing, why he walked away from all that manic feverish art-making, why the last piece in the Collected Writings was written 16 long years before he died. But now I admit to finding the loss, the waning of inspiration, the plain old silence, deeply sad, while also completely understandable. “We keep coming back and coming back / To the real,” Wallace Stevens writes in “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven,” “to the hotel instead of the hymns / That fall upon it out of the wind.” I nodded with recognition at Timothy Keane coming back and coming back to erasure, disappearance, dislocation, and desolation in his reading of Brainard. It is almost painful to leave this strip of beautiful beach and dunes behind. I confess my eyes welled up the other day when I heard Paul Auster recite the closing lines of Brainard’s very early, prescient piece “Back in Tulsa Again”: “I wept, that is, I continued weeping. I continued weeping for the rest of my life.” But, still, there’s always so much more possible: “baffling combustions are everywhere,” as Joe’s friend Ted said. All the scraps and fragments of the real still out there, waiting for someone to pick them up, hold them to the light — ready to be stitched together in new, dazzling combinations. I wonder if any single passage can sum Joe Brainard up, but for me, today, this one comes close:

what might have been

a different tomorrow today

in this dream of being awake

(past and present)

and silly with being alive.