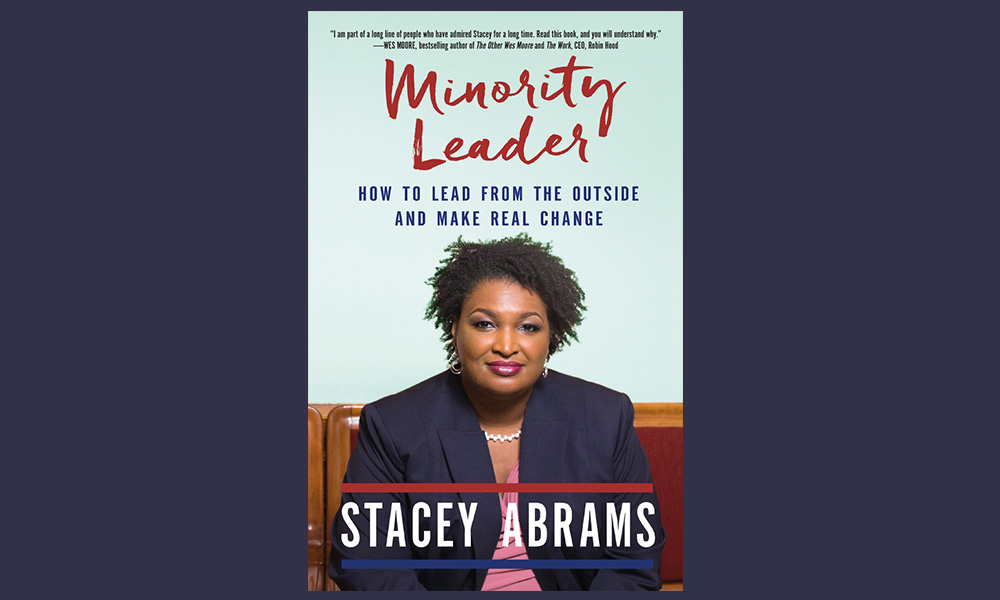

How might a self-respecting progressive Democrat today discuss the book focused on pursuing one’s personal entrepreneurial vision that she first published two years ago? How might a political leader facing some of the worst recent Republican voter-disenfranchisement initiatives pledge to “write our own rules” for the American political process, while convincingly castigating Donald Trump for doing the same? I posed these questions to Stacey Abrams, after her communications team told me that she would answer them. But that team then asked me to further simplify the questions, then refused altogether to respond. So, still with much respect for Stacey Abrams as a public figure, here are a few basic questions raised by her recent book Lead from the Outside: How to Build Your Future and Make Real Change (a republication of her Minority Leader: How to Build Your Future and Make Real Change), which, for whatever reason, Abrams’s coordinators first agreed and then declined to have her answer.

Abrams describes herself as an author, serial entrepreneur, nonprofit CEO, and political leader. After 11 years in the Georgia House of Representatives (including seven years as minority leader), Abrams ran as the 2018 Democratic nominee for Georgia governor, becoming the first African American woman named as gubernatorial nominee for a major party in the US. Abrams has founded multiple organizations devoted to voting rights, training and hiring young people of color, and tackling social issues at both state and national levels. She is the recipient of the John F. Kennedy New Frontier Award.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Power, in this book’s account, manifests through “years of experiences as a legislator, an entrepreneur and a civic activist.” But the act of gaining power here most often stems specifically from entrepreneurial engagements. So let’s say we start from a persistent opportunity deficit faced by women, and by people of color, in which, despite following “the rules for advancement as they understood them,” many individuals end up barely keeping “their heads above water.” Why might the entrepreneur (even more than the activist or elected leader) stand out as the basis for this book’s focused case-study on how leaders from the outside most effectively “gain and hold power”?

¤

Part of that first question comes from trying to fuse this book’s original emphasis on empowering individual professionals, with its new preface’s broader reflections on flaws in the functioning of American democracy. Or here I could point to an apparent tension between your opening chapter coaxing audiences to “run for office, take the helm at corporate boards…or start a small business” (so not necessarily forging wholly new economic and social structures), and its concluding chapter calling for “revolutionary change.” How most constructively to harness (within oneself, and within a broader diverse society) these drives towards personal upward mobility and towards revolutionary change — without having to sacrifice one for the other?

¤

This book’s new preface dramatically illustrates one recent circumstance in which playing by the rules (rules set, absurdly enough, by your actual opponent, who took calculated steps to further disenfranchise Georgia’s most marginalized political constituencies) seems bound to fail. Accordingly, this preface’s first paragraph declares: “my life…this book…are about knowing the rules and then deciding if they apply. Or if we need to write our own rules.” But how might this emphasis on “writing our own rules” need to get further parsed in an era when the president routinely undermines our rule of law and breaks with established norms? Or which previously written (though never genuinely realized) rules do you think enough of us actually could agree upon to help secure a less hypocritical and more stable American democratic culture?

¤

We’ve discussed how leaders from the outside might most effectively represent their communities’ interests. Could we also discuss how leaders from the outside can offer a distinct contribution for society as a whole? Alongside the countless useful “hacks” this book proposes for navigating one’s personal circumstances (amid the ongoing legacies of oppressive social categorizations), could you offer a few intractable-seeming political problems where we all might benefit by recruiting previously marginalized leaders especially attuned to recognizing how “limited resources often lead to extensive creativity,” and to excavating “the valuable in what is available”? And could you likewise talk about qualitative hacks, not just prioritizing the “how” or “how much” of getting things done, but the “why”?

¤

Finally, I’d love to place alongside your life as a legislator and entrepreneur and activist your life as an author. As a natural introvert committed to copious reading, could you describe how taking the time to craft a lovely opening line (“In November 1994, I entered a hotel room in Jackson, Mississippi, the dusk of late autumn broken by street lights that flickered against the window,” for example) might help you to accomplish much both in this book and in life more broadly? Or how might meticulously arranging words on a page help to infuse a politics premised upon changing the rules of engagement, upon redefining “winning” to fit one’s circumstances, upon rewriting as imaginatively as possible our collective destiny?