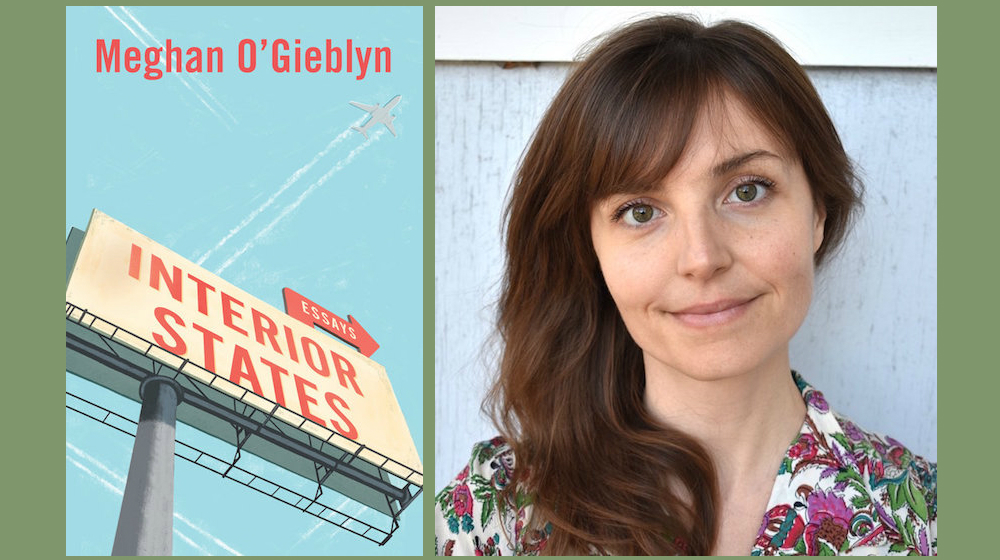

In “Ghost in the Cloud,” a remarkable essay published in n+1 last year, Meghan O’Gieblyn thinks through the ways in which contemporary Transhumanist thought, despite its claims to have inherited the Enlightenment’s skeptical rationalism, can be seen as a “a secular outgrowth of Christian eschatalogy.” In this essay — which introduced me to O’Gieblyn’s work — as in many of the others that make up her debut collection Interior States, she displays a knack for noting the traces of the religious in the supposedly secular, as well as the inverse. Raised an evangelical Christian until she abandoned the faith as a student at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, O’Gieblyn maintains a deep appreciation for both realms, yet a critical distance from each. This position — combined with her canny prose, keen intellect, and expansive curiosity — makes her an essayist of uncommon vision.

Interior States, which contains essays ranging in focus from the rebranding of Hell to Mike Pence’s ascendance to the vice presidency, traces the interwoven themes of evangelical Chrstianity and the Midwest. O’Gieblyn’s relationship to these subjects has to do not only with the circumstances of her life, but also, as she writes in the preface, with her “abiding interest in loss, particularly the loss of direction that occurs after the decline of a doctrine, an economy, or an entire worldview.” The result is an inquiry into the very heart of contemporary American life.

¤

NATHAN GOLDMAN: The essays that comprise Interior States span a considerable period of time — the earliest was published in 2011; the latest, this year. The majority appeared sometime between 2016 and now, but even so, I was struck by the sheer variety of ways in which the essays address your central concerns. At what point in the composition of these pieces did you begin conceiving of them as a unified project? Does having this body of work now collected and presented as something singular change how you think about the essays?

MEGHAN O’GIEBLYN: When I first started writing essays, around 2011, I had a dim idea that I wanted to write a collection and was quickly informed, by practically everyone who seemed to know anything about publishing, that collections are impossible to sell, particularly for a first-time author. Several people advised me to try linking my essays together into something that might pass as a memoir, and I tried this for almost a year before giving up. Part of the problem was that a memoir would have required me to tell the definitive story of how I left Christianity. I dreaded that finality. What I love about essays is the way you can approach an experience from a very particular angle, and the fact that you can keep returning to it across different essays, taking different approaches. Essays allowed me to circle that experience, over and over again, much the way certain contemplative or mystical theologians try to capture the nature of God through a series of negative or positive comparisons, while avoiding direct statements about the Divine nature itself.

Because I’d been told it was impossible to sell collections, I didn’t think of these essays as a unified project until very late in the process — essentially until I was contacted by Gerry Howard at Anchor, who asked whether I had thought about collecting the pieces. And it was really his encouragement and enthusiasm for the project that made me realize it could be a book. Some of the subject matter that I’d considered discrete — I had several essays on the Midwest and several others on Christianity — were actually linked by similar concerns. For one thing, the form of evangelicalism I was writing about was very distinctive to the Midwest and grew out of the theology of Midwestern evangelists like D.L. Moody. I also realized that what I was writing about, across these essays, was the experience of loss, particularly the loss of telos. The directionless feeling that I felt after leaving my faith is analogous, in some sense, to what many people in the Midwest are feeling at a moment when the industries and ideas that built the region — manufacturing, the American dream — have begun to seem tenuous and uncertain. So there is, I think, an underlying unity to the book, but that unity is evidence of my own intellectual obsessions rather than any deliberate strategy.

I liked that, in addition to the note in the front of the book that mentions the publications in which the essays initially appeared, each original publication is listed — along with the year of publication — at the end of each piece. This practice helped me to understand the book as something heterogeneous as well as a whole. And, because it made clear that the essays are not arranged chronologically, I felt it freed me from mistakenly reading the book as structured around a temporal progression. Possibly I’m reading too much into this subtle choice, but: was that your decision? If so, what was the reasoning behind it?

Yeah, it was my decision to include those details. The essays do represent, as you mention, an evolution in my thinking, so I wanted to ensure that readers understood which ones were earlier and which were later. And because some of the essays are tied to cultural and political events, I felt it was important to signal what was happening when the piece was written. So much has changed in the Midwest, and in the country as a whole, over the past few years, so I wanted to announce, for example, whether an essay was written before or after the 2016 election. I’m not sure if the publications are as crucial for readers to know. That may have been a sentimental gesture on my part, since I really value the relationships I’ve developed with these magazines over the years. I feel very grateful that magazines like this one, like Boston Review, Guernica, and especially The Point (where three of the essays in the collection were published) provided a platform for my early essays, and that the editors at those venues allowed me to do work that was, in retrospect, fairly ambitious for a beginning writer.

In the preface, you link your project as an essayist to the evangelical tradition of “testimony,” which you contrast with another Christian lineage of “confession” associated with the personal essay. Do you see your use of your own life in your essays as at odds with that other, more confessional lineage?

Around the time I was pulling the collection together in manuscript form, there was a rash of criticism — several pieces that appeared within a month or so — on confessional writing, arguing that recent memoir and personal essays were gratuitous and self-indulgent. This happens every few years, and the complaint, of course, is a very old one. But as I was reading those arguments, I began thinking about confession as a religious term and a religious posture, and what struck me was that it was completely foreign to my experience as a protestant, evangelical Christian. We didn’t practice confession as a ritual. To be honest, I always thought it would be wonderful to be Catholic, to tell all your sins to the priest and be granted absolution. In Protestantism, there’s no easy assurance — this was basically Max Weber’s thesis: You can never be certain you’re right with God, and this creates an ongoing sense of anxiety. The way we assured ourselves of our salvation, as evangelicals, was by “giving testimony.” Unlike confession, this was a decidedly public form. It was also, implicitly, an argument. You stood in front of a congregation and told the story of your life, emphasizing how God’s grace changed you. Rather than receiving absolution from a religious authority, your story itself was evidence that you were saved.

As an essayist, I’m interested in the extent to which my life can be a form of evidence, or can lend authority to an argument. I suppose what separates my work from what gets grouped under “confessional” writing is that I’ve always been interested in making arguments, or unsettling existing ones, so my experience is not an end in itself but a means to support whatever point I’m trying to make. But it also goes both ways: I’m using those arguments to make sense of larger questions that are very personal to me. Writing is a way to lend meaning to my experience, by putting my life in conversation with larger debates. This can be very satisfying, but it’s slightly more complicated, I think, than mere catharsis. I never feel unburdened by the writing process. I suppose this is how the protestant work ethic ultimately drives my own productivity as a writer: the anxiety always returns and gets channeled into the next piece.

I was struck by the case the essays in Interior States seem to make — not directly, but through a cumulative effect — for “former believer” as a category of identity with separate characteristics from “believer” or “nonbeliever.” Do you think of it that way?

Yeah, maybe there should be some terminology to mark us as a distinct religious category. I often think about the way people in 12-step programs still identify as an alcoholic or an addict years after they’ve stopped using, because that experience has become such a crucial part of their identity. Even though they left that part of their lives behind, they find it useful to hold on to it, to keep telling the story. It’s difficult to explain the deconversion experience to people who haven’t themselves experienced a loss of faith. People sometimes act like it’s this very childish revelation, like finding out that Santa Claus isn’t real, but it’s really a primal existential and ontological disruption. Religions are totalizing narratives, so abandoning such a worldview amounts to realizing that life has no meaning. For several years, I was paralyzed: all I could think about was how ludicrous it was that nobody knew why we were on earth, or how we got here, or what our purpose was. And I still have moments when those feelings return, all these years later. It’s strange to me that former Christians are often sheepish about acknowledging that experience as trauma. I think many of us feel a little guilty about it, like we got duped and were idiots to have believed in the first place.

Of course, there are really valuable things about having this perspective as well. Once you’ve lived inside the headspace of belief, you can always reinhabit it. You never forget what it feels like. And it gives you a lot of insight into how ideology functions, particularly in terms of group psychology and social control. Things that other people find bewildering, like cults, or fascist political regimes, I find it very easy to understand, because I’ve lived inside a totalizing system myself.

A recurring theme in the book is your experience, as a former believer, of the many beauties of faith, from the loveliness of the gospel music and the mass baptism that you compare to a Bruegel painting in “Dispatch from Flyover Country” to your remark in “Ghost in the Cloud” that you still find “the fundamental promises of Christianity beautiful, particularly the notion that human existence ultimately resolves into harmony.” It seems as if the appeal of certain aspects of the faith became clearer to you once you left it — for instance, in “A Species of Origins,” you write that “it was only after [you] stopped believing in God […] that [you] began to regard creationism as a deeply seductive belief system.” How has unbelief transformed your relationship to these aspects of Christianity?

When you’re a Christian — and particularly if you’re someone like me, who was born into it, rather than someone who came to it later in life — you never have cause to think about religion’s emotional appeal. It’s simply the Truth. It was only after I left the faith that I realized how solacing it was, for example, to be able to pray, or to belong to a community that shares a common objective, or to believe that history is authored and directional. And again, the thing that struck me hardest was realizing how much people benefit from — how much I had benefited from, without realizing it — the conviction that life has meaning. I always think of that Nietzsche line: “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.” It’s easy to dismiss faith as wishful thinking, the opiate of the masses, but it’s far more difficult to discount people’s need for meaning and telos. So, I guess the irony is that in leaving the faith, I became far more appreciative of how religion works to fulfill a very basic human need, its capacity to help people live.

I also became very interested in how other people fulfill those religious impulses. How do people who are atheists or agnostics find meaning in life? And I realized that many people seek religious experiences in seemingly mundane areas of life. Many of the essays I’ve written explore that idea from different angles. I write about how the Transhumanist movement and some of the more transcendent, speculative narratives about technology offer a secular version of the Christian redemption narrative. And I write about how narratives about motherhood often borrow the form of religious conversion narratives. One of the effects of us becoming an increasingly secular nation is that all these ostensibly non-religious areas of American life are becoming imbued with displaced religious energy.

One animating thread of Interior States seems to be the complicating of concepts (the Midwest, evangelical Christianity) that the American popular imagination tends to flatten. Was it ever on your mind to rethink the ways those things are often talked and written about? Or did that arise from the act of attentiveness to subjects that are often attended to carelessly if at all?

I think it would be fair to say that the starting point for every single essay in the collection was a desire to unsettle consensus. Each one grew out of the conviction that people were getting something wrong, or were talking about a subject in overly simplistic terms. I’d never considered writing essays about evangelicalism until I lived in a place — a progressive university town — where most of my friends and acquaintances were either atheist or agnostic, and where people often spoke of fundamentalists in a way that was very dismissive and one-dimensional. I didn’t necessarily disagree with their conclusions — obviously, I left the faith, so I shared a lot of their grievances — but I wanted to correct, or at least complicate, the premises, to show what was being left out. My writing on the Midwest grew out of a smiliar impulse. I began writing about that subject after the holidays one year, when a lot of my friends who’d moved to places like New York and California had come back to visit. They all had the same complaints about the Midwest; it was like they were reading the same script. Everyone kept griping about how boring it was here, how it was a cultural dead zone, how people in the Midwest were provincial and small-minded. Again, it wasn’t that I didn’t agree, in part, with that diagnosis. And it’s not like I set out to prove any of those ideas wrong in my essays or to reach a definitive conclusion myself. The point was to complicate the story and to make those conclusions feel a little less easy.

You’re also a fiction writer. How does your fiction-writing inform your essay-writing?

I was a fiction writer first. I started writing fiction around the time I left Bible school. I was reading a lot of Russian novels at the time, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, and had zero familiarity with contemporary fiction, so I believed novels were a way to talk about these big philosophical and existential questions that obsessed me. I somehow got into an MFA program, and it was there that I realized it was impossible to tackle those kinds of ideas within the confines of psychological realism, which is what everyone was writing at the time. I couldn’t make the arguments I wanted to make in a direct way, so I tried to disguise them as “thematic” concerns, which ended up making my stories muddled and needlessly oblique. When I started writing personal essays, it was such a relief because I was finally able to say what I wanted to say directly. The ideas could take center stage. But I do think that fiction taught me some valuable skills that carry over into nonfiction: an attention to language, how to pace a story, how to build an emotional arc. And now, of course, fiction writers are doing such interesting things. I love the novels that Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Rachel Cusk have published over the past several years. Their fiction often feels like essays, or even philosophy. I’ve learned a lot as an essayist from reading their work, and I think if I ever go back to writing fiction, I’d likely want to do work in that vein.

What are you working on these days?

I’m working on a book-length project. Nonfiction. It’s the first time I’m writing something this long, and it’s still evolving, so I’m hesitant to say too much about it at this point, but it’s been exciting and a bit daunting to work on something of this scope.