As a college classmate of mine, Bruce Handy, notes in his new book, Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult, fairy tales, “in their original, unadulterated, 120-proof versions, are so gruesome and bleak, even barbarous, as to raise the question whether they should be thought of as children’s literature at all.”

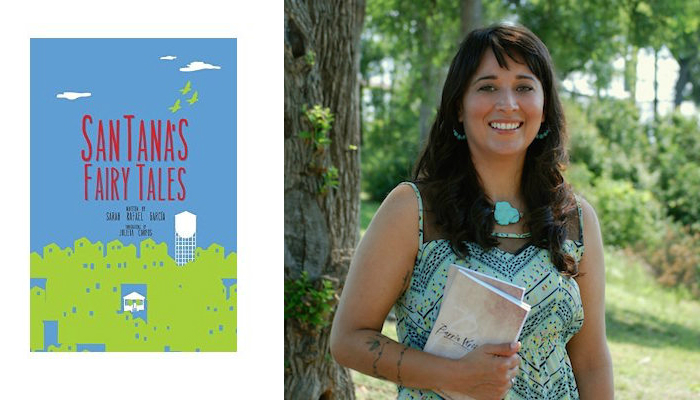

Well, there’s no doubt that Sarah Rafael García’s bilingual short-story collection from Raspa, SanTana’s Fairy Tales, is not for the very young, despite the fact that many youngsters populate its pages. García drew inspiration from the darker elements of the classic fairy-tale form to address the often painful history and stories of the Mexican and Mexican-American residents of Orange County’s City of Santa Ana, her adopted hometown. But the ogres, monsters, and spirits in these fairy tales are ICE agents, land developers, bigots, and other enemies of García’s community.

These tales are all the more chilling because, despite the otherworldly nature of her narratives, they are rooted in reality. This collection is as stirring as it is brutal, and García’s skill as a storyteller is on full display in these carefully crafted stories.

The book also owes its existence to the very community García writes about: its publication was supported, in part, by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, through a grant supporting the Artist-in-Residence initiative at Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana. In their original form, García’s stories were the center of a multi-media, collaborative, community event.

García is not only a writer, but she is also a community educator and an avowed traveler. She is the author of Las Niñas (Floricanto Press, 2008), and her writing has appeared in many publications including LATINO Magazine, Outrage: A Protest Anthology for Injustice in a Post 9/11 World (Slough Press, 2015), La Tolteca Zine, and the Acentos Review, among others. García is a Macondo Fellow and an editor for both the Barrio Writers and Pariahs: Writing from Outside the Margins anthologies. One of García’s best-known initiatives is the LibroMobile, a literary project by Red Salmon Arts and Community Engagement, that integrates literature, visual exhibits, and year-round creative workshops and live readings in Santa Ana.

¤

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: What attracted you to the fairy-tale form to tell the stories of your city?

SARAH RAFAEL GARCÍA: Interestingly, I started writing fairy tales after studying in Ireland while completing an MFA program in creative writing. I had a very challenging experience obtaining my Masters degree: the program itself lacks diversity and support for students of color, and even more so for first generation graduate students. During my last year, my thesis year, I decided to not submit my initial thesis project to avoid receiving additional critique on my culture and language use in a historical novella I’m writing. Ireland made me realize that I could use another form to tell my stories, a form people around the world are familiar with and that is also part of pop culture.

Fairy tales and fables are classic styles used time and time again, so I started writing feminist short stories incorporating some of the characteristics of fairy tales and fables in order to offer a counter narrative to female narratives, as a way to turn the male gaze back on society, making society accountable for sculpting our stereotypes. And in that collection, I also wanted to include the transwoman narrative, and that’s how the first SanTana fairytale came to exist. “Zoraida & Marisol” was inspired by undocumented, transactivist Zoraida Reyes.

The idea to pitch a multi-media project for a Santa Ana collection evolved after a couple of conversations with CSUF Grand Central Director/Chief Curator John Spiak and few rereads of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales to offer an opposing view of “the happiest place on earth” neighboring my city. I knew I wanted to do a series of stories and offer a history of the all the changes occurring in Santa Ana — the artist-in-residence and exhibition allowed me to grow those ideas. In a way, it was nostalgia for my childhood home and my own family’s immigration story to Santa Ana that initiated the fairy tales.

Specifically, what narratives were you trying to respond to or counteract with your stories?

Personally, I can’t imagine writing anything without focusing on my own identity and community, which includes plenty of labels: Chicana, Tejana, Santanera, first-generation college graduate, first born in the U.S., woman, never married, no children, feminist, Mexican, American, and the list can go on based on who you ask about me.

But one goal for this project was to show that cities don’t need to bring in artists or entrepreneurs from other areas to “revitalize” a city — a counter to the current gentrification and displacement issues in Santa Ana and across the nation. By investing in folks currently doing the work at the community-based and/or grassroots level, cities can help empower their residents, artists, and local independent businesses.

Santa Ana is approximately 80 percent Mexican-American among many new immigrants and undocumented residents who — a relatively large percentage — are also bilingual. Growing up in Santa Ana, I never read a book in Spanish or heard of books that reflected my community. Developed through a one-year onsite artist-in-residence at Grand Central Art Center, SanTana’s Fairy Tales was more than a bilingual book, it was a visual art installation, oral history, storytelling project that integrated community-based narratives to create contemporary fairy tales and fables that represent the history and stories of Mexican/Mexican-American residents of Santa Ana (inspired by the Grimms’ Fairy Tales). The exhibition highlighted — and my book includes — the stories that focused on the day-to-day problems of most of our residents, from cultural landmarks being removed to fears of deportation and police surveillance.

The second half of your book consists of Spanish translations of your stories. The translations were done by Julieta Corpus. Can you talk a little bit about the process of translation and your working relationship with Julieta?

Part of the project is to collaborate with other community-based artists, naturally focusing on the Santa Ana community. But I also wanted to include folks who share my passion as well as my priority to include the Spanish language.

I’ve known Julieta Corpus for several years and she lives in my birth town, Brownsville, Texas — I’m happy I could also support another community who has contributed to my identity. I admire her poetry as well as her skills to write beautifully in both English and Spanish. I thought of translating myself — Spanish is my first language and I also minored in it during undergrad — but I knew it would take more time away from writing the other stories and I would find it challenging to be lyrical when I mostly code-switch in Spanish rather than speak it regularly. Plus, who better than a poet to translate a fairy tale?

The translation process consisted of me finishing a story, doing edits with César Ramos from Raspa Magazine, and then sending a final version to Julieta. Julieta and I would usually teleconference to review the Spanish version and decide on certain translations, for example do we translate “low-rider” or is it just “low-rider” in Spanish too? Then César would review the Spanish one more time for consistency. Both César and Julieta were the magic behind the translations. It has been so empowering to read my work in Spanish, especially because I know I would have not done it as well as Julieta. She does such an amazing translation — sometimes I forget I’m reading my own work!

[To watch a video of Sarah Rafael García work on SanTana’s Fairy Tales as a multimedia, community-based, collaboration, visit here.]