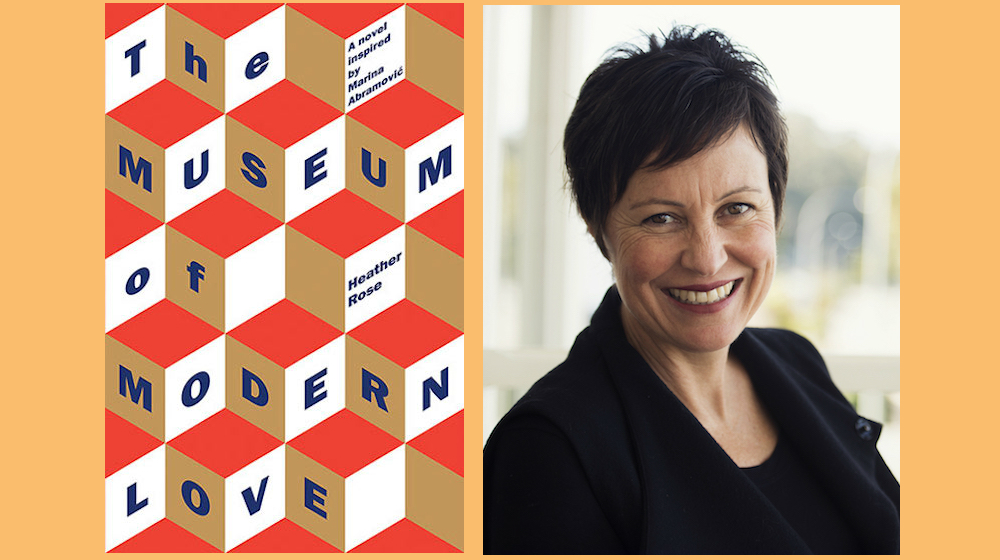

Heather Rose has a varied writing practice, crossing genre and mode from crime to science fiction to literary fiction. She currently lives in Tasmania, but has previously been based in a number of international locations. Her book, The Museum of Modern Love, won the Stella Prize and will be released in America by Algonquin in late November. We caught up ahead of her conversation with Marina Abramović at MoMA’s Atrium on November 28th.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: How did you come to writing?

HEATHER ROSE: I was listening to a talk by Wayne Dyer today and he was discussing the concept of a “burning desire.” That’s what writing has always been for me. A burning desire. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t passionate and curious about writing. Long before I had English in its written form, I scribbled across paper and when asked by my mother what I was doing, I’d apparently reply with some ferocity at age three, “I’m writing!” I’ve also been a passionate reader. As a child I read everything I could get my hands on. I grew up in Tasmania, an island to the far south of Australia. We didn’t have a lot of books at home but I read everything on the shelves. Children’s books, adult novels, biographies, the dictionary, encyclopedias, anything that would help me understand the world. My father took me to the library every week too. It’s gone on from there.

I still read widely. I love literary fiction, but I also love fantasy, poetry, historical fiction, sci-fi, children’s literature. I am mesmerised by books. Not just their words and ideas but the feel of them in my hands and the smell of them. I have an entirely synesthetic relationship with books!

I’ve been a professional writer for almost 40 years. I had my first paid gig as a writer at 17. I wrote the weekly windsurfing column in the main Tasmanian newspaper. I then went on to become an advertising copywriter. My first novel was published when I was 35. And I’ve done a lot of business writing. With the success of The Museum of Modern Love, I’ve been able to apply myself (at least for a little while) to my own writing full-time.

In Australia we don’t have a culture of philanthropy. We don’t have Guggenheim or MacArthur Fellowships. Government funding of the arts is incredibly hard to get. We also don’t have cheap domestic help the way you do in America. So Australian women are pretty busy. We’re doing the far greater share of domestic labor and care of aging parents. I was too determined to be a writer to wait until the kids were grown. So there were a lot of years with very late nights as I wrote my novels. I have lovely memories of the children making notices for my office door saying “Do not disturb. Mum is writing!” They were always supportive. They’re all artists too.

Your recent novel, The Museum of Modern Love, dovetails with this in that it is about creative practice, including contemporary artists (like Marina Abramovic), music composers, teachers and gallery patrons who all gather in New York. Where did this novel come from and what was it responding to in your own creative life?

The novel was inspired by a photograph I saw in an Australian art gallery. It was of one of Marina Abramovic’s shows back in 1974 in Naples called Rhythm Zero. Abramovic put 72 items on a table and for six hours she was entirely passive and the audience could do whatever they wanted to her. The 72 items were both benign — a loaf of bread, a rose, a feather — and less benign — a chain, a gun, and a bullet. (The audience almost killed her.) The descriptor beside the photograph in the gallery also said that Abramovic was known for another performance called The Walk. Abramovic and her then-partner, Ulay, walked from either ends of the Great Wall of China over three months to meet in the middle and end their relationship. I was intrigued by someone who could be so brave and at the same time so romantic. And I thought, “There’s a character for a novel.”

For the first five years, I fictionalized Abramovic in the novel, but after I went to New York in 2010 to see The Artist is Present at the Museum of Modern Art, I realized I could no longer fictionalize her. It was then that I sought permission to include Abramovic as herself in the novel. And because she is a woman of extraordinary grace and courage, she said yes. With no caveats.

As the novel developed over 11 years, it became a sort of love letter to women of art and to creativity in general. To me the novel explores the fragility and the power of the creative process — and the depths to which we, as artists, have to go to convey our hearts and minds. The Artist is Present attracted over 850,000 people over 75 days. More than 1500 people sat opposite the artist. There is an entirely secular and a deeply spiritual aspect to all Abramovic’s performances and that dance — between the secular and the spiritual — attracted me. The novel is also about love, marriage, commitment, grief and connection. You know, all the easy things!

The Museum of Modern Love is often quite touching with a healthy sense of fate, optimism, and sentiment. Can you explain how this feeling was cultivated?

I am very interested in the way we connect with each other. We have random meetings with strangers that touch us for years, and even a lifetime. We have moments of profound connection with each other. Life is so much in the unseen. For me, characters walk into my life. If they communicate emotions, if they are vivid, it’s because they come fully formed. I was in love with acting during my teenage years and, in some ways, writing is a form of acting for me. I have to inhabit these people. It’s only by the end of the novel, I understand what they are all doing, and why they’ve stepped forward into the book. I often feel like a conduit between the seen and the unseen.

People ask writers where our ideas come from. But for me there are so many ideas, and what is curious is which ideas I choose to pursue. Every creative idea is a doorway. The characters in The Museum of Modern Love experience that too. They are drawn to the Abramovic performance for many reasons and it opens them up. There’s a film composer Arky Levin and his absent wife. There’s a journalist Healayas Breen, a teacher Jane Miller, a student from Amsterdam, a famous art critic, a daughter. There’s a ghost and a muse too. Stella Adler said, “Life beats down and crushes the soul and art reminds you that you have one.” I have been moved by art so many times in my life. It was wonderful to work with a cast of characters in the novel who were experiencing that too.

What is the hope of art in our contemporary age? What is the role of writers, artists, musicians in the present, not only in this novel, but beyond?

Ah, that’s a big question. I think we will always be trying to understand and convey this strange thing called life. I believe that we artists are trying to do that through story. Whether that’s in paint, dance, film, words, music, theatre, sculpture, any of the art forms, we are all attempting to convey the stories of humanity as we interpret and experience it. Our forms may change but not the impetus. Nor, I hope, the desire in our audiences to hear, see and experience stories. As women we are starting to have more of our stories heard and appreciated. That’s taken a long time, but it’s incredibly important as we create a new balance in the world.

If we are drawn to interpret life through a creative medium, then we have an invitation to do that to with as much commitment, curiosity and vulnerability as we can muster. I love that my life has given me such an invitation.

I think that we underestimate creativity at our peril. I would love to see imagination taught in schools. I believe we are depriving our children of their future personal wealth if we do not teach them to harness the power of imagination. Whatever field they go into, creativity is the skill that solves problems, enriches thinking, inspires innovation, illuminates our sense of self and grows connections with each other. Isn’t that what a full human life is?

The role I think changes depending on where one is — to be a writer in Tasmania is not the same as being a writer in New York, for example. How did you negotiate writing about New York as an outsider to the city? What was the lure of writing about this place?

I’d been to New York for the first time in 2008. I actually owned an apartment up in Harlem for six years. During my twenties I did around 20,000 road miles through the west and mid-west of America. In some ways I know the American landscape better than I know the Australia landscape. I love so much about America. And I love New York. I’ve spent a lot of time observing New York both close at hand and from afar.

I didn’t choose New York for the novel. It happened to be where Abramovic in her fictional form was based, and then in her real form, actually lived. It’s the city where the performance at the heart of novel — The Artist is Present — takes place. I felt at home the moment I arrived in Manhattan and I go back regularly — especially now I have US publishers for both my children’s and adult novels based in New York. I have dear friends in New York. I subscribe to The New York Times! Like many of us, I’ve read many books set in New York. And of course I have watched many films.

I went for several weeks during The Artist is Present. I waited in the queues and wandered the Museum of Modern Art and stayed at The Chelsea Hotel and imbibed the city. I sat opposite Marina Abramovic four times. The Artist is Present was mesmerising and intriguing. The way people responded to her was raw emotion. There was an inexplicable beauty to it all. When I got home to Tasmania, I was glued to the live feed off the MoMA web-cam for hours at a time! I knew I had to write the novel as if I was a New Yorker. I could never have written the novel the way I did without all the research.

I went back the following year, in 2011, for more research on the city. I went back to MoMA and stood in the atrium and, of course, Abramovic wasn’t there. I felt winded. I think the performance will always live in that space for those of us who experienced it. The lovely thing about the book is so many readers have told me that now they feel as if they experienced The Artist is Present too.

What has The Museum of Modern Love opened up for you? Has it led to a more developed interest in place, in art, in identity, in inspiration, in relationships? Can we expect to see any of those concerns in the next book?

I love the wonder of life. The Museum of Modern Love is my seventh novel. It has been the most highly awarded and the most widely published internationally, so in that regard this novel has been an extraordinary gift to me as a writer. Each of my novels both for children (as Angelica Banks) and for adults (as Heather Rose) have taken me to rich places literally, intellectually and emotionally. I actually fell in love with painting during the writing of The Museum of Modern Love. So much so, I enrolled at art school!

I also think the character of Arky — the film composer who we follow throughout the book as he grapples with his art and his heart — taught me a lot of appreciation for the creative process. There’s no use holding back in art. Perfection, the ideal circumstances, knowing what’s ahead, all that is secondary to simply putting your hands on the keys and playing. Seeing where the music of your creativity takes you. Everything unfolds from there if we have courage.

My next novel is a political satire set in Tasmania. I’m having a lot of fun with it. Whether it will have any overlap with the other novels, we will have to wait and see. The main character hails from New York, although she’s a Tasmanian by birth. So I’m home again in my imagination for the meantime. And it’s my happy place.