Mauro Javier Cardenas’ formally experimental debut novel Revolutionaries Try Again, out September 6th from Coffee House House Press, probes the question of whether or not a novel should even be concerned with narrative. It suggests that, instead, it is the depiction of our internal minds that matters. An Ecuadorian expat who lives in San Francisco returns to Ecuador to attempt a run at the presidency with his friends from high school. But what follows is not a tale of political hijinx, it is an exploration into the interiors of the characters as they navigate their dark, cold worlds.

Each chapter is a mutiny against narrative schemes — with entire chapters written between em-dashes and backslashes. It forces us to think about how we choose to tell — or not tell — a story. I spoke to Mauro about the difficulty of form, and how to write a novel in which nothing happens.

SAM JAFFE GOLDSTEIN: This book is unconventional in so many ways; yet a conventional narrative — four high school friends seek each other out amid a time of political upheaval in the hopes of political and personal redemption — does exist beneath the surface. Why does that novel not exist? Did that novel ever exist?

MAURO JAVIER CARDENAS: No, it didn’t. I don’t write with a scheme or a plot. The novel really began with the question: what happens if Antonio goes back to Ecuador? I soon realized he wasn’t going to do anything, and that I had absolutely no interest in creating a typical narrative in which they were now going to run for president. That was not really what excited me about the characters, and it’s not really what excites me about fiction. I don’t think fiction is the right vehicle for tracking events, plot, and action. I think what the novel does really well is perform the interiority of human beings. That’s what I’m interested in.

So much literature of exile and return is about redemption. Were you aware of those kinds of trappings while plotting this novel, or thinking about the way that it should look or feel?

Absolutely. I had in my mind Love in the Time of Cholera — a character studies abroad and returns due to nostalgia, and as soon as he lands he realizes he’s made a mistake. So I was aware of that narrative, of immigrants who want to go home, and the few that actually go back home regret it. At the same time, they are seeking a lost past.

I think it’s important to be aware of the traditions, especially when it comes to a literature of exile and return. Otherwise you end up focusing on things that are quite familiar and already explored ad infinitum.

In a lot of ways, this book is about failure. Antonio returns home and nothing works out, nothing happens. Was it hard to write a book about failures?

About 15 years ago I was taking a workshop with this very traditional guy. He was into narrative, plot, and conflict-action-resolution. I remember telling him: “Antonio is going to go back to Ecuador and nothing is going to happen.” He was like, “How are you going to make a novel out of that? He has to do something, right?” That stayed with me, because I hated everything he stood for, and everything he thought narrative should be, but it forced me to think about what else can fiction do, outside the conventional mode of narration. How do you create a sentence that can be alive on its own, without having to try to move the narrative?

Often you hear people ask: what does this passage do to move the story forward? That, to me, was another one of those things. What if I write sentences that don’t move the story forward? That are alive on their own? There’s a passage in the novel, where Leopoldo is on the bus to the party to meet Antonio and Julio, and he’s talking about the Virgin Mary. He’s remembering this moment of being in the mountains. You could take that particular experience and make it into a whole novel. Yet I was more interested in seeing what happens when tremendously important things happen to you, and yet you still have to live your life. You still have to get on the bus and go to a party. Not everything has to be tied to some kind of grand action, because you still have to go through the quotidian movement of life.

While the book largely feels “of the everyday,” miraculous things do happen. Why do you include miracles?

Magical thinking is all around us; it’s part of being a human being. It just so happens that this magical thinking was married to the Catholic religion, where you see magical thinking being manifested in so-called miracles. Given that these characters grew up in the world of Catholicism, it was very natural for them to be enmeshed in it without it being some momentous thing. It’s just one more ingredient in the soup they are drinking to make themselves believe they can change their country.

The idea that they can return and become the leaders of Ecuador is so brash. Where does that confidence come from?

That was one of the questions that interested me quite a bit. What drives you to think that you can change things? If you were to ask people anonymously whether they have the desire to change things, some might say no. What drives certain people to want to help strangers have a better life? That was one question that I was trying to explore.

I think part of their brashness comes from their being good students. They won this big academic contest, were top of their class. They know how to give speeches, happen to know the right political people, and are friends with this really rich guy who might help them with the campaign. All these things can add up to the delusion of believing that they have the right backbone to do something.

There are a lot of different tones in this book converging at once, which is both the pleasure and the difficulty of reading it. Were the transitions between those tones something you worried about at all? Did you care that those transitions would not be easy or simple?

What I cared about was tracking the characters’ thinking moment-by-moment in a way that represented what their thoughts would be. I tend to get bored of novels where the same person is always speaking, or it stays in one tone for a long time, no matter how wonderful the voice. And I get tired of how things look on the page.

So I just wanted the flow to be the flow. That meant being true to the organic flow that would hopefully be a better presentation of a person’s interiority. The thing I did pay a lot of attention to was sound. Sound can help you move quickly from one spot to another, from one tone to another, from one time-period to another. When you’re reading two things that are somewhat disconnected, you can connect them simply because they sound similar.

How hard was it to decide whether this the right form for each chapter?

There were a few decisions made along the way that were neither hard nor easy — you just pay attention to what’s happening on the page and then you ask yourself questions. For example: I wanted Rolando’s world to be written in a different way from Antonio and Leopoldo, because he comes from a different world. At the same time, I was aware of what some writers say: “the character dictated the form.” That, to me, sounds like bullshit. Because text is text and form is form. So what I wanted to do with Rolando was chose a form at random, and then let the form dictate the character. That, to me, feels true.

I came upon this book Summer in Baden-Baden by Leonid Tsypkin. He uses em-dashes in a way that I thought was wonderful. So I decided to take those em-dashes and do something different with them, let them dictate what the characters would be like. That’s how the decision was made on the Rolando chapter. The other one I’ll mention is the Alma chapter, where I use those backlashes you often see in poetry. That came from re-reading the novel, and seeing that I often use those for songs. I thought Alma’s fate was so horrible, the least I could do was give her the gift of song.

The book feels like a manuscript covered in red ink. But as the reader, I can’t see that red ink. It feel somehow both meticulous and unedited. How were you able to create that balance?

Part of what I was trying to do was make sure each section had its own rules. I was not letting one chapter dictate necessarily what happens in the next chapter. But at some point that’s not possible. My approach was to focus on each section, and then go back and see the ways the chapters were connected. What are the ways through form and syntax you can make them feel a little bit more connected? For example, after I was done with all the Rolando chapters — when I was using all the em-dashes — I realized I was interested in having Rolando’s form destroy the rest of the novel, in some way. So I went back to many of the sentences with Antonio and Leopoldo and added those interjections — it became a way of linking Rolando, in a kind of subversive way, to the rest of the novel.

Nostalgia is a thing we do not want to be trapped by, or we want to escape from. Would you call this book a nostalgic book?

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being nostalgic. Nostalgia is just one more feeling that we have. When I came to the United States from Ecuador there was no internet, and the only way I could communicate was by making a very expensive phone call. There was much more of a disconnection then than there is now. That exacerbates nostalgia. So the question becomes: what do you do with that nostalgia? Do you let it determine your life such that you don’t live fully where you live? You have to be able to allow yourself to feel nostalgia, but at the same time you also have to make sure that it does not overrun your life.

As you ask in your book: how are we to be human in a world of destitution and injustice?

I think it’s an impossible question to answer. The right answer, in my mind, is that you should drop everything you’re doing and go help others. I think in a world like ours, it’s easy to conclude that we should drop everything and go help others. But it’s very difficult for us to take that answer seriously. Because we like mushroom risotto, we like to read on a Sunday afternoon, and we like to go dancing.

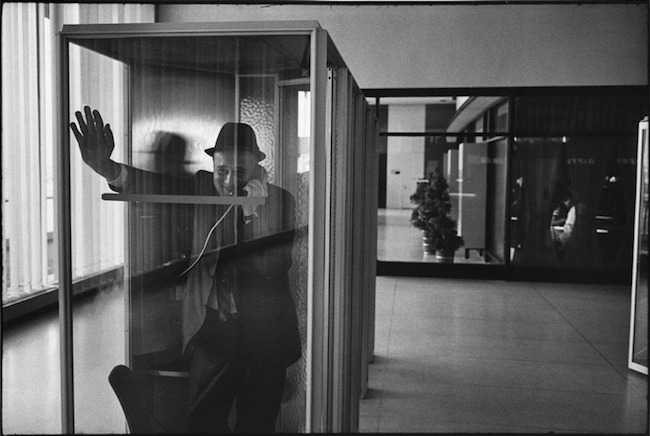

Header photo by Garry Winogrand