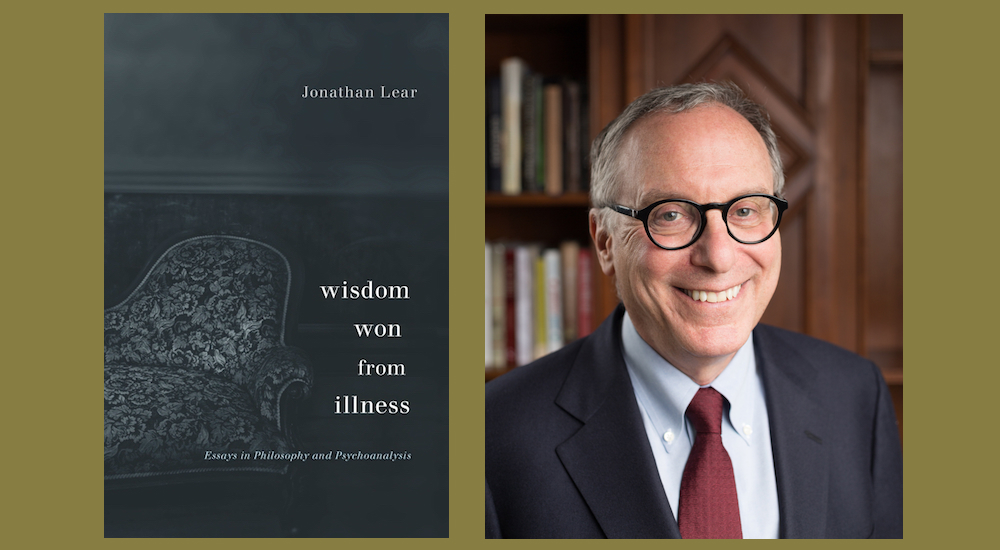

How might our absorption of Platonic dialogue parallel our infantile (then ongoing) incorporation of an erotic pantheon including parents, care-providers, educators, role models, projected rivals? How might our most acute philosophical discussions prepare us for our most freely associating therapeutic sessions (and/or vice versa)? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Jonathan Lear. This present conversation (transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman) focuses on Lear’s recent collection Wisdom Won from Illness: Essays in Philosophy and Psychoanalysis. Lear teaches philosophy at the University of Chicago, where he directs the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, a collaborative research center. Among Lear’s books are Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation and Aristotle: The Desire to Understand. His Freud was rated number one by the Guardian in its top ten books on psychoanalysis. He is both a trained psychoanalyst and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

¤

ANDY FITCH: It seems fitting to ask you about a few myths. So first, before fleshing out possibilities for psychic integration, could we turn to one classic source for categorical demarcations — Socrates’s noble lie (or, in your terms, noble falsehood), according to which:

“All of you in the city are brothers,” we’ll say to them in telling our story, “but the god who made you mixed some gold into those who are adequately equipped to rule, because they are most valuable. He put silver in those who are auxiliaries and iron and bronze in the farmers and other craftsmen. For the most part you will produce children like yourselves, but, because you are all related, a silver child will occasionally be born from a golden parent, and vice versa, and all the others from each other. So the first and most important command from the god to the rulers is that there is nothing that they must guard better or watch more carefully than the mixture of metals in the souls of the next generation.

Here perhaps Socrates deliberately presents individual citizens as interdependent wholes (saturated with singular faculties, coaxing forth well-balanced social harmony), and we could consider it narcissistic to seek a psychological description where the Republic offers a polis-centered myth. But a canny correspondence between tripartite models from Plato (for the polis, for the soul) and from his distant descendent Freud (for the psyche) adds to the frustrating sense that Socrates’s falsehood provides all elements necessary for a dynamically integrative civic and/or psychic model, and then goes out of its way not to mix them. And here I would consider it especially helpful to bring in your distinct perspective as psychoanalyst/theorist/scholar. Amid the Republic’s ongoing city-soul analogy, Socrates’s call for strict social hierarchy does correspond to what Wisdom Won from Illness’s opening chapters characterize as Plato’s fundamentally inaccurate depiction of healthy human function — with Plato presuming conflictual, exclusionary relations between, for instance, “proper” judgment and “unruly” desire. Yet your book’s subsequent chapters also make the case for this noble falsehood’s significance deriving less from its repressive or politically conservative implications than from its epistemic radicality (its delegitimation and/or deliteralization of all foundational myths). So within that twofold repressive/revelatory context, and proceeding from the baseline assumption that this noble falsehood crystallizes philosophy’s incapacity to account for the animating powers of irrational psychic forces (not just sporadic disruptive impulses, of course, but a whole parallel, primordial, ever-present modality of mind, memory, assessment, calculation), to what extent do you conceive of the Republic as ensnaring us within the phobic characterological pretense of its authoritarian social arrangements, and to what extent do you detect liberatory potential in Plato showing Socrates transparently outlining the distorted foundations upon which any social/psychological/philosophical framework (presumably our own included) has been built? Or when, then, late in the Republic, Socrates reminds us that this text’s ambitious political program primarily has served to magnify the study of the soul, how might we reinscribe Socrates’s reliance upon his noble falsehood less as oppressive/repressive governing tool than as precocious precursor to your own more recent claims that “we are still in early days…of understanding what we mean by truthfulness, psychic integration, or unity”?

JONATHAN LEAR: You raise several different possibilities for how we approach Plato, especially when we start to think not just as scholars of ancient philosophy. I prefer to focus less on the inheritance of Plato’s thinking than on how Plato might continue to matter. What can we learn from Plato to help us figure out how we now should live in the world? To address that question, I take up the Greek phrase often translated as “noble lie.” I don’t consider that the best translation because it implies an intention to deceive, whereas a more accurate translation would cover fiction more broadly. I think that Plato doesn’t describe a deception here when he discusses what kinds of fiction we need to educate young people and to help them become good citizens. Plato points to a problem we always face as humans, and which arises today in acute and threatening forms: in what healthy ways can we bring people from youth into society and into a culture so that they will flourish personally and socially? What kinds of stories should we tell them to help them? Two generations ago, during the immediate post-World War II period, a consensus reigned about the types of “noble” stories to tell our children: about America, fighting the Nazis, about freedom, democracy. Our society itself contained great injustices, but these stories still operated at a broad level of generality, and they did not begin by providing perfectly accurate, rational arguments. So the point is not to praise those postwar narratives. We definitely should critique them. But they do offer an example of the need humans feel for fictions that help us to shape and fall in love with our ideals. The question becomes: how to address that need without valorizing the injustices of the age?

In terms of your specific question about the particular story that Plato or Socrates constructs in the Republic, this falsehood embraces a class hierarchy that I consider unjust, and I don’t think we should tell stories about each person having distinct metals inside them. So Socrates’s example of a noble falsehood is deeply flawed. But that still seems a different issue from trying to tell the truth in mythical form, which is crucial for a culture to remain vibrant and inviting. For example, nations all over the world now face challenges arising from massive migrations. Fearful, threatening, and hate-filled fantasies have emerged, and spread like wildfire. Are there ways to respond with supportive cultural vehicles (songs, poems, music, films, video games) that can help everybody come together as citizens of a healthy polis? One can disagree with the particular story Plato devised, and nevertheless think that he has raised a tremendously important question about how to educate a person into becoming a citizen.

You also raise the basic question of how we might better understand ourselves, as the complicated human creatures we are. How can we better address the non-rational, emotional, and desiring aspects of ourselves, from the point of view both of individual happiness and of societal well-being? What is the relation between social justice and human happiness, deeply understood? Again this problem takes us back to Plato, Socrates, Aristotle. What role can self-conscious thinking play in directing our lives towards happiness and freedom? How can we deal best with the non-rational parts of our human functioning? I see psychoanalysis as taking up those questions in a particularly valuable way, for instance when it asks: what would it mean to take account of the whole psyche (with its rational and irrational functionings)? How would such self-understanding contribute to individual happiness and social freedom? In a way, this is a question of how to inherit the concerns of the ancient Greek philosophers.

So as you suggested at the end of your question, psychoanalytic thought follows closely how we move from infancy into culture and adulthood, but it also recognizes that humans are quite remarkable in that they don’t just develop from childhood to teenage years and then into adulthood. When humans develop psychically they take some of their childhood with them. When maturation goes well, adults can deploy forms of playfulness that go way back in their lives, to take pleasure in art, for instance. Art can resonate throughout one’s ever-present psychic history. Psychoanalytic thought allows us to see that we don’t just have a psychic history in the abstract — we actively preserve our psychic history, and keep it alive in the present. For all these reasons, stories will continue to matter, will continue to provide occasions for playfulness as well as for recognizing and appreciating those parts of ourselves that we tap by engaging with art and philosophical arguments.

Pivoting then to related topics of pedagogical/therapeutic midwifery, could we consider one additional enigmatic myth, that of “the true city,” a city which Socrates presents in distinction to the fevered Kallipolis:

They’ll build houses, work naked and barefoot in the summer, and wear adequate clothing and shoes in the winter…. They’ll put their honest cakes and loaves on reeds or clean leaves, and, reclining on beds strewn with yew and myrtle, they’ll feast with their children, drink their wine, and, crowned with wreaths, hymn the gods. They’ll enjoy sex with one another but bear no more children than their resources allow, lest they fall into either poverty or war…. We’ll give them desserts, too, of course, consisting of figs, chickpeas, and beans, and they’ll roast myrtle and acorns…drinking moderately. And so they’ll live in peace and good health, and when they die at a ripe old age, they’ll bequeath a similar life to their children.

Here Socrates does offer a clarifying illustration of one city type that he considers healthy (and stable, whereas Kallipolis we learn someday will collapse). Yet Glaucon abruptly terminates the account, characterizing this “city for pigs” as unworthy of sustained attention. Socrates, unusually compliant, bows to Glaucon’s taste, moves on. Or has Socrates already told us everything we need to know about the true city, through this fleeting, disrupted, quite cursory glance? Does the polis depicted here promote its own form of injustice, given that its self-sufficient citizens might find satisfaction with relative ease, with less reliance upon each other? Or conversely, might Socrates have meant to imply that any such well-balanced psychopolity would deserve a wide berth, a preservatory isolation from Athens’s destabilizing excesses and urgencies? Or with this understated gesture of letting his mythic city dissolve on the spot, has Socrates simply demonstrated that an absence of pathology offers little room for prognostication, for dialectical pursuits? Those types of interpretive questions came to me upon first reading this passage. But Wisdom Won from Illness, with its depictions of pedagogical/therapeutic midwifery, prompts more precise relational questions focused upon Socrates’s present audience, Glaucon, exemplary possessor of spiritedness — quality of soul most conspicuously absent from this city for pigs’ peaceful, sated, status-indifferent community. So does Plato present Socrates completely failing to communicate to his current interlocutor? Or to what extent might one consider Socrates’s stomach-heavy account of true citydom as deliberately designed to provoke young Glaucon (aroused by such deprivations of spirit) until he might mature to more rational appreciation for this community’s mellow, mild, sturdy if less stirring (less heroic) civic/psychic fulcrum? And of course Socrates’s triangulated engagement with Glaucon via the city for pigs parallels Plato’s triangulated engagement with his reader. So has the Republic once more intuited, hinted, adjusted for the fact that we, like Glaucon, might not yet possess the right mindset for persuasion on purely rational grounds? Or again, how does your combined psychoanalytic/philosophical/scholarly training attune you to productive potential lurking within dialogue’s triangulated propensities? What more might you add about our irrational, impulsive, appetitive/spirited side’s most positive impact upon shaping an animated, creative, virtuous, syncopated sense of self, even amid our farthest-reaching philosophical speculations?

For the City of Pigs passage, I start from a picture that gets painted in words, this picture of a healthy city where, roughly speaking, everybody eats chickpeas and a healthy vegetarian diet, with small bean desserts. Then Glaucon comes along and asks: “What about relish?” I sense Glaucon pointing to a certain zest for life, a peculiarly human life, one that the City of Pigs does not accommodate. We can keep giving pigs roots or corn (or whatever they like), and that can satisfy them again and again. They do not need relish. But humans quite literally feel a zest for life that expresses itself in developing a zest for relishes, for spices from far away, for pastries — for foods that are not necessary to sustain life, but are tasty and interesting. This both expresses our humanity and poses a problem for us. The question becomes not “How could we ever get away from all of that and return to a city of pigs?” but instead: “How can we embrace our humanity, which includes disruptive needs for relish and a zest for life, without thereby falling into terrible inequalities and injustices?” Your questions about pedagogy and midwifery take us into conversations about these basic problems, into conversations where we cannot assume anybody possesses the final answer, where we try to figure out how to live best as the complicated, self-disrupting, happiness-seeking, and confused animals that we are.

Both the Socratic conversation and the conversation within psychoanalytic settings are oriented this way. Socrates claims that reason should rule over the whole psyche, because reason is wise and has foresight. Here I am not confident that “reason” is a good translation, but whatever term we use should suggest a capacity of psyche to think, through language, in informed and responsible ways. Socrates makes the point that, while lots of animals think, human thinking includes a linguistic formulation, which includes thinking of who we are, of what the world is like, of how we feel. We share these linguistically expressed concepts and can make judgments with them. So Socrates asks whether we should deploy our capacity to understand ourselves (that is, for self-consciousness) to think through how to live life well. Psychoanalysis is a continuation and development of that thought. Psychoanalysis seeks to create conditions in which one’s feelings, emotions, conflicting perspectives, and conflicting desires can be expressed in language and thus enter our thoughts in an open-ended way. We can then begin to ask: “Which of these thoughts do I want to live by? Which would I prefer to discard?”

I think of that process as a form of midwifery, because nobody in the conversation knows in advance what answers might emerge. It is too much to say that the Socratic philosopher and the psychoanalyst only draw out what is “already there,” but it is crucially important that they do not try to instill any particular dogma or belief. You can make many contrasts between philosophers and psychologists, but they share a knack for facilitating conversation. They cannot say ahead of time what thoughts will emerge. But they share the midwife’s skill in keeping the process moving.

There is one huge contrast between how conversation plays out in psychoanalysis and Platonic philosophy. Over and over again, Socrates comes upon someone in the marketplace, somebody facing a problem, and they start talking. The term logos itself often gets translated as “language,” but part of its meaning has to do with the responsibilities we take on when we engage in conversation. If somebody asks “Do you know what the weather’s like outside?” and I say “Yes, it’s raining,” that person can ask me a second question: “How do you know?” or “Why do you think so?” It is not alright for me to say “I have no idea.” And if I say “Because I feel a twinge in my pinky,” I ought to have a theory that my pinky tends to hurt when it rains. I need to be ready to offer some broader, intelligible account.

But psychoanalytic conversation involves taking a sabbath rest from that kind of conversational obligation. For the sabbath hour of the psychoanalytic session, you really only need to follow one rule. Freud called this the fundamental rule of psychoanalysis, the rule that you have to say aloud whatever comes into your mind, however silly, embarrassing, or shameful it might feel. The psychoanalytic session suspends the everyday rules of life and of speaking, rules which Socrates, Plato, Aristotle thought were internal to logos. Ironically, you break the psychoanalytic rule if you continue to constrain yourself and to organize your thoughts around these everyday rules of discourse. You shouldn’t inhibit yourself in any way at all, so that you can listen to and express all sorts of different voices that happen to be among your internal voices, but which you don’t normally acknowledge because you are too busy staying on task with ordinary life and obeying the rules of discourse.

So both philosophy and psychoanalysis depend upon dialogical conversations, but philosophy often focuses on figuring out which argument works the best, whereas the psychoanalytic situation reverses that emphasis. It says take a rest from stating your beliefs and giving reasons, and let us just see what comes to mind.

You raised another important point on how processes of internalization present a challenge to our understanding of who we, as humans, are. Again our capacity eventually to develop a mature, adult self-consciousness capable of rational thinking remains dependent upon a prior process which is to a significant degree non-rational. Even an infant brought up with loving parents and supportive teachers will not only take in their teachings, but in fantasy will take these people in as well. They become internal figures (fantasies of Mom, Dad, teachers, dogs, teddy bears) who partially constitute one’s sense of self. When Plato and Freud characterize us as erotic creatures, they mean that, in our relations with others, we fall in love, we absorb others, we find it almost impossible to let them go and move on. It is a deep psychoanalytic insight that when we take in the teaching we regularly take in the teacher. That can raise serious problems in life.

The problems can be poignant and hilarious at the same time. At the beginning of the Symposium one of Socrates’s followers, Apollodorus, says that he has made it his job “to know exactly what Socrates says and does each day.” But though he may remember the words and the actions, he does not really understand him. It is as though he thinks that to “follow Socrates” he needs to put on fancy sandals just like Socrates’s and literally follow him through the streets. So what kind of conversation helps a person recognize that, if I want to “follow” Socrates, I need not dress like him, but rather live quite differently than I currently live?

If we are lucky socially speaking, we might end up internalizing loving, thoughtful people, and loving, thoughtful ways of being. But not everyone can count themselves so lucky. So what does one do when one has already become a person who would need to change significantly in order to live a happy life? How does one address that fundamental human challenge?

Well within the multiple potential models of incorporation that you just sketched, could we situate more precisely Plato’s audiences themselves undergoing complex processes of simultaneous, kaleidoscopic, perspectival incorporation — pulling readers in multiple vectored directions, and perhaps thereby making them more conscious of these incorporations (rather than, say, simply identifying with an author, then closing her book, then picking up the next)? Recently it has struck me, for instance, to see consistent reference to your graceful account, roughly 20 years prior, of an isomorphic (rather than analogic) principle at play in the Republic’s city/soul parallels: “Psyche and polis, inner world and outer world, are jointly constituted by reciprocal internalizations and externalizations; and the analogy is a byproduct of this psychological dynamic.” Here when “Inside and Outside the Republic” describes internalization as a process akin to infantile graspings at the unknown (“Our ultimate dependency is manifest in the fact that we internalize these influences before we can understand their significance”), or externalization as akin to successful projections of the soul (“the process, whatever it is, by which Plato thought a person fashions something in the external world according to a likeness in his psyche”), I’ll imagine dialogue itself as exemplary textual/allegorical/experiential arena in which these reciprocal processes can take place: with readers ingesting characters’ stated arguments and implicit assumptions before being able to weigh the relative merits of these claims; with readers projecting themselves into the dialogue through a variety of ever-shifting identifications. So again potential textual isomorphisms (of Plato and Socrates, Socrates and reader, Plato and reader, reader and composite sense of justice) return us to broader philosophical and psychological concerns of whether/how conversation can delineate a constructive conjectural space (akin in some ways to the analyst’s office) in which we need not purge threatening or dangerous or enigmatically eroticized elements, but instead can bring them under (relatively) rational rule. So with certain recent queer-theory projects revalorizing emulation and imitation, I even could see trying out Socrates’s sandal fashions as not necessarily such a bad philosophical debut after all. And then for much more broadly isomorphic/hermeneutic comparisons: does projectively imagining (simultaneously witnessing and performing) Platonic dialogues only offer a source for proper internalization if, by luck, or by hard work, we get their embedded message “right”? Or, conversely, do we in fact need already to have undergone integration in order to read a dialogue or treat a patient with proper care? Can encountering isomorphic Platonic mechanisms help, say, seasoned psychoanalysts reflect upon their own “unusual practical capacity of mind,” cultivated while getting caught up in patients’ therapeutic transference? If therapists have to continue cultivating deeply irrational means of interpersonal engagement that most professional practices (with much professional practice of philosophy included) forbid, what else can therapists tell us about how to read Plato?

I agree that a real critique would have to emphasize the inadequacy of imitation as our sole pursuit, while still acknowledging potential benefits of imitation. But your point fits nicely with what I meant about taking in the teacher with the teaching. Quite often, taking in the teaching does involve taking on certain characteristics of the teacher. I had a beloved psychoanalytic teacher who eventually became a good friend. We would meet in the evening after his day of clinical work. It was his habit to make himself a martini before dinner. He would make me one too, and we would sit around and talk about psychoanalysis. When I have a martini now, decades later, I remember him with delight, and remember various things he said. Of course, this routine would misfire if I believed that all it took to learn from him was to drink martinis every night. But I also shouldn’t forget the productive pleasure of imaginatively lingering in his presence as I sip a martini. Plato understood that.

And I also agree that, having just now discussed differences between philosophical and psychoanalytic dialogue, we also should go back and consider further similarities. When we bring together dialogic forms of philosophy and of psychoanalysis, I think that the broader category of “therapy” can cover both of them. Philosophy can have a therapeutic intent, particularly when it means to change the reader through an engagement with the text. Plato, for example, seems to have thought that his dialogic form would engage readers in ways that straightforward argument would not. Søren Kierkegaard comes to mind as another philosopher whose writing can grab the reader and convey a certain efficacy through the power of the word. Psychoanalytic conversation, likewise, has to find a form that makes the right kind of difference for its participants.

This relates to the unusual practical capacity of mind you mentioned. It turns out that insight into oneself is often not sufficient for change, even if one wants to change. One can ask, “Why do I keep breaking up with people in such abrupt, painful ways?” And one can come up with some excellent answers, and yet the unhappy-making routines stay pretty much the same. And yet there are other occasions (and these can seem almost magical when they occur) where the insight is so powerful it can change everything all on its own. What is that power of understanding when it works in such a remarkable way? Self-consciousness can start to play a powerful role in changing a person. But how do words gain that power, so that through understanding them one can restructure the soul? That is when poetry matters for example — when it can take on that efficacy and make a huge psychic difference.

Two decades ago, your own work called for the transdisciplinary establishment of a Plato-inflected psychopolitics. Today, Wisdom Won from Illness calls for a philosophical anthropology. Psychopolitics presumes a field of inquiry in which clinical mechanisms no longer get considered absent of lived social context, and in which political scientists’ interpretive models address the dynamic psychic structures shaping each individual’s distinctive forms of social agency. Could you outline philosophical anthropology’s comparable project? Do these parallel-seeming enterprises take their respective place on any personal and/or historical timeline worth discussing? Do they again prioritize differing aspects of a shared commitment to pursuing practical wisdom (less a theory of the good than its actual doing or facilitation)? Do they develop divergent discourses, yet both seek compelling forms by which to coax forth rich, textured, multivalent communication? And how, precisely, does “anthropology” factor into this intimate assessment of our own capacities for self-conscious judgement? And what to make of the apparent paradox that, in fact, philosophical anthropology sometimes emerges as even more interventionist than psychopolitics: seeking, like Plato, not only to describe health but to promote it; calling, like Aristotle, to change certain political structures in order to encourage human flourishing; pushing beyond, say, Freud’s call for stoicism in the face of purportedly timeless, universal social discontents? If the Republic strives, amid an imperfect world, to promote psychic harmony within its reader’s soul, then what ought the reader do with such a soul, and how might psychopolitics and/or philosophical anthropology assist in and/or benefit from the completion of that integrated project?

I have been thinking about these questions for a while, and I hope my thinking has changed and developed over that time. One problem, stretching back to ancient Greek philosophers, has to do with their teleological conception of the human being and our place in the world. Plato and Aristotle thought that, even though it might be difficult to work out, the world was such that there could be a good fit between individuals having a happy fulfilling life and society flourishing. Part of our modern inheritance involves recognizing that this harmony, if at all attainable, is much more difficult to obtain than we might have assumed. Many accidental processes also shape individual psychic development, as well as social and political development. So I have tried in various ways to ask what we can do about these additional complexities. We shouldn’t abandon the ancient political project of thinking through how individual well-being and societal well-being might fit together. But we need to recognize the difficult, fraught, and fragile nature of this project. We need to ask which political, psychological, and social forms can best help to address this project and to make a real difference.

Plato articulates in the Republic a conception of how society structures our individual thoughts. Social structures direct our psychic development before we even can make rational choices about how we want to be influenced. And that psycho-social influence in turn shapes what becomes culturally, intellectually, artistically possible. So the ancient Greeks ask: “Can we think through our current social and political situation, the world’s justice and injustice, the nature of the psyche and the nature of society, such that this thinking can help us understand what’s happening all around us? And then, through that understanding, can we make things better?” On the one hand, you can sense a discontinuity there between the moderns and the ancients, but also continuity.

I want to emphasize both elements in my work. What commands my admiration of and commitment to the human (and I don’t mean at the expense of other living beings) is not just to have one more biological species on Earth, not just to make sure this species continues, but that within this species have developed elaborate capacities for understanding, for creativity and generosity, for love and acceptance, for justice. That fragile, wondrous biological phenomenon needs nourishment. From the time of cave paintings until now, humans have created art and thought about why things should matter, how the cosmos came into being, how we should live. Within that human and humanistic context, the value of learning for its own sake, for the sheer delight of understanding, emerges in the universe — though that is a value under social and historical threat right now. At present, many prominent voices ask: “Why don’t we just learn skills that will make us better technological producers? What public goods could the humanities ever offer?” This is a serious threat to civilization (to culture) and it seems to me a shame that the answers are not obvious to us all.

You ask about my interest in philosophical anthropology. There is an ambiguity in what we mean by anthropos. What do we mean by “human being”? Does this just refer to a biological species, or also to certain ways of being human? I don’t want to develop some restrictive ideological narrative of what being human entails, but raising those questions about the meaning or value of being human is part of what it means to be human. Yet we also have to see the vulnerability of everything I just described. I have been thinking more about how to hold onto this thought, and how to support it. One can understand “anthropology” as this word was understood at the height of imperialism and colonialism. Not only would imperialist and colonialist countries conquer other lands — they would send people to write books about these regions and their populations, so giving a “logos of anthropos.” But Heidegger pointed out another way to make a logos, where we don’t give the logos of some people we treat as other, but rather we, as anthropos, speak for ourselves. And what does it mean for us to give our own logos, not in terms of studying people from a scientific point of view (even if those people happen to be ourselves), but rather in terms of what we have to say for ourselves. That is another sense of what “anthropology” could mean: humans speaking our own being. So when I refer to “anthropology,” I too want to ask: “What do we have to say for ourselves?”

[Extended Plato quotations come from C.D.C. Reeve’s revised version of G.M.A. Grube’s translation of the Republic.]