By Sam Ribakoff

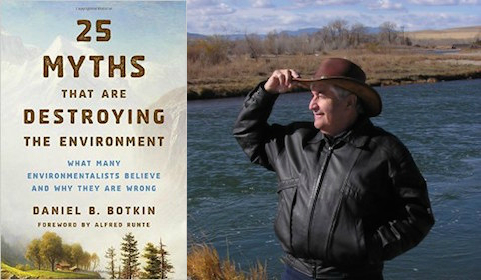

Daniel Botkin is a world-renowned ecologist and professor emeritus at UC Santa Barbara’s school of Environmental Studies, who has worked on many conservation efforts around the world, including at California’s Mono Lake and Michigan’s Isle Royale National Park. He’s also a published author with a knack for poetic titles; The Moon in the Nautilus Shell, Discordant Harmonies, and Beyond the Stoney Mountains all invoke the beauty and complexity of nature and the environment.

These books are comprised of a mixture of Botkin’s thorough research and careful accounts of his own field work. He grapples with the ancient idea of “the balance of nature,” which suggests that ecological systems are naturally stable and harmonious unless otherwise disturbed. Botkin challenges this idea, and instead writes about an environment that’s constantly changing and adapting. Botkin intended these books for a mass audience of non-scientists to understand cutting-edge research and ideas in ecology and environmental sciences at a time when global climate change has made people increasingly interested in learning about the field.

Botkin has long been known in the scientific community for his unusual stance on climate change. His most recent work, 2016’s 25 Myths that are Destroying the Environment: What Many Environmentalists Believe and Why They Are Wrong highlights that dynamic. Gone are the poetic titles and florid writing of his earlier work, 25 Myths is meant to be an honest, direct examination of what Botkin believes to be many popular myths about the environment and ecology. Some passages include highly controversial statements like “little of recent climate change can be attributed to human actions,” and, “carbon dioxide plays a much more minor role in climate change than the public is led to believe.” To try to summarize his complex views, he believes that the causes of climate change have less to do with human action and the effects of climate change will be much less destructive than perceived to be. Instead, Botkin describes 10 ecological problems that he believes are much more pressing: energy, habitat destruction, invasive species, endangered and threatened species, forest management, fisheries management, access to fresh water, toxic substance pollution, access to phosphorus and other essential minerals, and lastly, climate change.

When Dan and I spoke over the phone, he was in southern Florida where he’s writing his next book, although, he swears he’s giving up science for folk music. “Singing folk songs brings people together in these divisive times,” he says. “There’s a truth in music that isn’t in science. In music you can either sing in key or you can’t. You can either sing in harmony or you can’t. You can’t fake it, whereas you can bullshit science.”

SAM RIBAKOFF: This book is drastically different in style from your other, more hard-science books. Was your intention to write something that was accessible to people without a scientific background?

DANIEL BOTKIN: Oh yeah, absolutely. I’ve gone to many, many workshops about the environment, and seen pundits and politicians and journalists who really didn’t know any science make pronouncements about nature and the environment and how it worked and what was wrong. They’d be in total belief of things that were absolutely false, so I started to make a list of them, as well as another list of what the right statements were. I showed them to my friend Charles Mann, author of 1491 and other books, and he said: “this is great Dan, you have to publish it.” Then I showed it to Al Runte, the person who wrote the foreword to the book and a great historian, and he said: “Dan, you have to stop being so polite. You’ve come up with these polite, poetic titles to your other books, and the people who don’t agree with you are just ignoring you. You have to write a book called 25 Myths that are Destroying the Environment.” So that’s what I did. So yes, It’s meant to be readable by everybody. I started working on human effects on climate change in 1968 and I wasn’t doing it casually. I have an undergraduate degree in physics. When I started working on climate change I asked myself the question, “how could it be that a very trace gas like carbon dioxide could have a big effect on climate?” I was a professor at Yale at the time, and I spent six months of research seeing how this could happen.

Are the environmentalists mentioned in the title of the book academic ecologists, or are they journalists, pundits, politicians, and environmental activists?

Well some of the myths are believed by many in ecology, specifically the “balance of nature” myth, which is still how a lot of environmental science is done. For example, I talk about how there’s this belief that populations exist due to the logistics growth curve. It’s an explicit mathematical model of “the balance of nature” — that a population will grow to this perfect, fixed state, and the births will always equal the deaths unless people disturb it. That has been in use as the basis for how to manage fisheries since 1945, and it is totally mythological. No population has been shown to actually grow in the wild as according to the logistics growth curve. The climate models are steady state models, they believe that if the climate is not disturbed, it reaches a constant condition.

Do you think people who feel that climate change is an important issue might be turned off by the title?

Al Runte and I had a lot of discussions about that. Al was right in saying that whenever I’ve written about climate change, it’s been ignored. Heavily ignored. He was right, too, in thinking that coming up with a controversial title was a way to get people’s attention. I said to him the same thing you said, and Al said “Good. Maybe they’ll feel they’ll have to read the book then.” He saw it as advertising in that sense.

What do you think about the reviews from conservative publications, using your book as a tool to say that climate change is a hoax?

You found stuff like that? You know, whatever you write, especially about something as controversial as environmentalism, there will be people who twist it in ways you didn’t intend.

I’ve worked on climate change since 1968, I was one of the earliest people to believe that we were very likely causing a warming. I did a lot of work for the EPA on forests and their endangered species. Through the 1980s the weight of evidence seemed to support that we were causing global warming, then the data started to turn around. It then became clear that we were not really capable of having an effect. If only we had the power over the Earth to control something as complicated and massive as the climate. Then, a lot of articles started to come out that were very fraudulent; one in particular said that 15 to 30% of all species were going to go extinct in the next 30 years. The New York Times asked me to read it and interview the writer, and I was shocked because his method was totally wrong, and since then the whole topic has become ideological and political.

Based on recent research, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s very likely that we are having very little effect on the climate. I’ve come to the conclusion that this isn’t our major problem, that we were leaving behind the nine other major environmental problems that I talk about in the book. Those are really, really serious problems, but nobody talks about them. The effects of climate change on species is going to be very minor, and species are adaptable. I testified before Congress in 2006 and told them what I’m telling you, and nobody invited me to talk anywhere until I gave a talk in Long Beach at the Aquarium of the Pacific in 2008. Neither side wanted to hear what a careful scientist who had studied this for 45 years had to say. So I hope this won’t become a discussion on climate change, because I’ve decided to stop working on that. I want to promote the other environmental issues which are likely to get us into trouble. It’s very despairing, because since I was a boy I really loved science, but climate science has become so politicized.

I don’t think many people outside of the scientific community think of ideological constructs when they think of science.

It started off that way, and Galileo got into a lot of trouble over it. I make the point that science isn’t a consensus, it’s a debate. I have a picture of Niels Bohr and Einstein sitting together very chummily, but they had this major philosophical distinction. Bohr was a proponent of quantum mechanics, which says that randomness is a fundamental part of the universe. Einstein said: “God doesn’t play dice with the universe.” Now that’s about as fundamentally different as you can get. But they were friends, they were scientists.

Why do you think the “balance of nature” theory has such a hold on your field, and on the public?

It’s an idea that was written down by the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers; it’s a very long-standing myth. Part of it is aesthetic, part of it is this desire for consistency in life. There’s this wonderful book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay, and he discusses why people get into these mass beliefs, and he says there are three fears that drive people: the fear of insufficient food, the fear of death, and the fear of destructive changes in society. Stability and consistency are very strong drivers for people. They want a world that’s stable.

You write in the book: “I am saddened to say that I do not think we are in the position to solve many of our environmental problems from solid science.”

Yes! All of those nine ecological problems that I mention in the book, including climate change — the science behind them is very modest. There’s still an awful lot that needs to be known. There’s still an awful lot to know about how nature works. Environmental systems are amazingly complicated and they don’t work like mechanical systems.

I guess when I read that, I thought, well, if these problems can’t be solved by science, then can they be solved by policy and politics?

Well the science is being prevented because it is so political and ideological.

Do you believe that the worst of these problems can be restrained by implementing decent policy?

Oh yeah. I wouldn’t have gotten in and stayed so long in ecology if I didn’t believe these things could be solved. It isn’t that the world is infinitely incomprehensible, although maybe I should ask some string theorist about that. When I was at UC Santa Barbara, I was the chairman of the Environmental Studies program. Different state agencies would ask me to advise them. Mono Lake is 250 miles from Los Angeles, and it’s a big saltwater lake. When you went out there in the 1980s there was this sign that said “Welcome to Mono Lake. You are permitted to walk here courtesy of the city of Los Angeles.” The city of Los Angeles just went out there and said this is Los Angeles land. They just took it. It was providing 17% of the fresh water for the city of Los Angeles, and it was the best quality water.

1.3 million birds used Mono Lake for resting and migratory feeding because as a salt lake, it had brine shrimp and brine flies, which are their primary food. The city diverted all the streams from the Sierras away from Mono Lake, so there was no more surface fresh water coming into the lake. An environmental group called the Mono Lake Committee fought to get the city to stop taking the water. They managed to persuade the state government to pass a bill that said there had to be a scientific study to determine whether the water removal was going to destroy the lake, because the city was saying there would be enough rainfall to balance the lake out — again, the steady state theory. They came to me and asked me to run the study. We did some surveys and made some models of the depth of the lake and the evaporation rate. It’s my philosophy that scientists should not dictate public policy, so instead, we presented the graphs to the people of California and the courts that showed the declining rate of the water. We said: “It’s up to you, the people of California, if you want Mono Lake to be at its lowest level, the most aesthetically pleasing, and with the most bird habitats, or do you want it so it’s just barely alive, or somewhere in between? It’s up to you.”

The court that made the decision, prior to our study, had said that the city could remove water from the lake until it could be demonstrated that there were negative effects. After our study the court completely reversed itself. No more water could be taken from Mono Lake by the city of Los Angeles. So you can solve these problems, but it takes good scientists that are not swayed by the “Al Gores” of the world. You have to be very open-minded. You have to be able to observe despite your prejudices.

Do you think the problems that you lay out are problems that people who are not scientists, and don’t have the scientific knowledge about those problems, have any right to participate in, in terms of advocating for policy on those issues?

That’s a really good question, and it’s a simple answer. They don’t have a right, they have an obligation to get involved, but they have to do it like the way the Mono Lake Committee did it. They can’t do it in an empty-headed way. A lot of the big environmental groups have done a lot of good. In a democracy this is an obligation. There are a lot of small groups doing great work too, groups that take the science seriously. You get involved the same way that you choose who’s going to represent you politically. You have to search for people who you believe are trustworthy, honest, and seek out science. It’s not easy, but there are these people out there, and they are amazing. Join these organizations, make it your hobby, and take it seriously.