Who among us is not spending most of her time trying to understand the complexities of the times? How can we even begin to grapple with it all? Is comprehension even possible? Osama Alomar’s very short stories (or in Arabic, “al-qisa al-qasira jiddan”) do not offer answers. What they do provide is a necessary reminder of the importance of protecting the human spirit — a worthy touchstone, when confronting darkness.

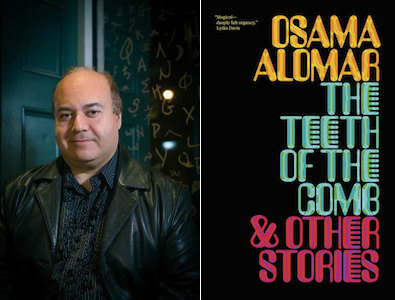

In his allegorical stories, sometimes just a sentence long, Alomar anthropomorphizes concepts, objects, animals, and nature, animating them to create parables about the trials of daily life. Alomar began his career in Damascus, Syria, where he lived before immigrating to Chicago almost 10 years ago. New Directions published Alomar’s first work in English, Fullblood Arabian, in 2014, and recently released his collection The Teeth of the Comb & Other Stories. Both are translated by C. J. Collins. Alomar and I spoke about his recent move to Pittsburgh for the City of Asylum program, the power of the imagination, and how to bypass censorship.

SAM JAFFE GOLDSTEIN: What was the journey to getting The Teeth of the Comb and Other Stories published?

OSAMA ALOMAR: It was through my agent Denise Shannon, who was trying to publish my first book in English. She sent my manuscript everywhere, and finally New Directions accepted it. They published my first book, the pamphlet Fullblood Arabian, in January 2014. That was my first English publication, and The Teeth of the Comb is my first book-length work in English.

How does it feel to see your books translated and out in the U.S.?

I am really happy, because this was my goal. That’s why I decided to immigrate to the U.S. — to establish my name as writer in English, here in the United States, and to be free.

Do you feel that you have been able to establish your freedom?

There are no absolutes in life; there’s no absolute freedom, but it is much better than the freedom of the Middle East. Here, I can talk. There is a lot of tolerance. I have met really nice people, and my best friend and translator is American — C. J. Collins. I first met him in Damascus in 2006, then he became my best friend.

How has the translation process changed for you? Your first book was translated by C. J. Collins, while the second was translated by both of you.

Both of those books were translated by C. J. and me. We translated in the front of my cab in Chicago. As people say, necessity is the mother of invention. I had to work seven days a week, and I could not stay home and translate because I would lose money. We had no choice, I had to work and at the same time translate, so my cab is where most of these translations happened.

Some customers were surprised when they noticed my dictionaries and books. Some of them asked, “what are you doing?” I told them, “translating stories,” and it was surprising for them. C. J. and I tried our best to be honest to the original text. It was very hard work, and it took us a very long time. We revised the whole text many, many times.

What is it like to write a parable? Do you find it easier to find freedom in parables?

A parable means that you can get wisdom out the story. In the Middle East, I do find it easier to find freedom in parables, because it can take more than one interpretation.

I understand that your short stories come out of a specific Middle Eastern literary tradition. How do different audiences respond to your work?

In Syria, people told me that my stories were very strange, but they also liked them. American audiences encourage me a lot, even more than my Syrian audiences. I don’t know why, but Americans respond well. Especially at events, I notice their reaction right away. They like the black comedy of them — that these stories can make you think and laugh at the same time.

Can you talk about your use of humor?

I wrote most of these stories when I was in Syria, and because of the dictatorship most of my stories are political and social. However, there was also very strict censorship, and I used humor in my stories to allow for more than one interpretation, to avoid being censored. It also allows you to realize the difference between one reader and another, how their experience changes their interpretation of the story. There is also something in my nature; since I was a teeenager I have loved these kinds of stories. I read Aesop’s fables and Franz Kafka. Kafka was not only a writer, he was a philosopher. Many people think that he was gloomy, a cynic, but he predicted what’s going on right now. Especially Metamorphosis — I love this story. It is a very strange story, but it is also a projection on our present life, and our future life, too.

What are the benefits of writing stories that can have multiple interpretations?

Some might understand it as a social story, others as a political story, others can understand it as a story about nature and animals. I write a lot of stories about animals, and people who love animals tell me: “I love your stories, because you talk about animals and nature.” There are many differences between people.

Is it difficult to bring animals to life?

No, it’s easy for me, I love this style. From the beginning I have written this type of story. Because I love animals, I love nature, and I also love anthropomorphism and personification. There is always projection on humans in these kinds of stories, with animals, nature, and even with objects.

How do you decide to bring something to life? In one of your stories, human dignity is a character — what are the steps you take to turn human dignity to life?

I cannot control the idea, it comes all of a sudden like a shooting star in the sky. It comes, for instance, from thinking about a tree, a blade of grass, a hedgehog, a wall, from anything. Then I start to work on the idea, sometimes it takes a few days, sometimes a few weeks, sometimes months. But the idea imposes itself on me. I get ideas from everywhere, because my mind is always working on something. Especially when I start reading books or creative works, I can get inspiration from my reading. If I feel that I need to get more ideas, I start reading. I read short stories, novels, and philosophy, I love philosophy.

What philosophers do you read? How do they influence your work?

I love philosophy; my father was a philosophy teacher and he influenced me a lot. When I was a teenager, I wanted to read these books but could not, because they are very difficult. As a teenager, it is better for you to read literature. Later I started to read the philosophers who discuss human rights. Especially the French philosophers Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu. They influenced me a lot.

How do you hope literature helps human rights?

In my first book in English, Fullblood Arabian, there is a story entitled “Human Rights.” I imagine human rights as a beautiful woman. People rape her, kill her, crush her, and take very nice perfume from her body. Literature can make us more aware; people like to read stories and novels much more than they like to read philosophy. With my stories we can talk about literature and human rights and dignity in a pointed and artistic way. Then people can go read about human rights and dignity.

Who are your stories written for?

I always try and write my stories to all people, not to any specific group or people. I’m always trying to write about love, about fate, about human dignity, about human rights, about equality. Especially now, because there is so much hatred. Our world is very small and there are no barriers between hate and love. We need to get rid of all this hatred. However, it looks like the opposite is happening right now.

Something that comes up in your stories is that ideas are dangerous. How do your stories confront dangerous ideas?

I hope that my stories can make more awareness about what’s going on in Syria, and wherever people are under persecution. Whether they are facing a regime, or getting tortured by their government.

A word that you use often in your stories is “tyranny.” Do you feel that American readers need to be more aware of this word and this concept?

In my stories, my goal is to create awareness about tyranny in the Middle East and Syria. Now everyone knows Syria because of the war, and this is based on the tyrannical regime. Now the Syrian issue is number one in the whole world. So, through mine and others’ writing, we can be aware of tyranny in general and especially in the Middle East. We live in a very small world, some people think of Syria as a very far place, even as another planet. What goes on Syria now affects the whole world. There are Syrian refugees everywhere now.

Your stories are very imaginative. Do you find that people need more imagination?

No. People have very good imaginations. I always write stories for everybody, because everyone has a smart mind. I want all my readers to be creatives readers and to think about my stories. That’s why I do not go directly to the political, I want my reader to use their mind to get the idea, to work on the idea.

Are you ever a character in your stories? The story Journey To Me feels so personal, like I’m hearing about your life.

I wrote this story in Syria and it was published in Syria. I was not talking about myself, but about humans in general, about human psychology and human spirit. I think the human spirit in a psychological way is much bigger than humans, and much more complicated than our universe. I was also influenced by Freud and Jung in this story.

As a writer that investigates the human spirit, how do you think we should understand it? What are some of the tools we can use?

I think it is very difficult to understand it. Even with the most genius psychologists, it is almost impossible. The main tool is imagination. Not only in writing but in all kinds of creative works, even in science. Imagination is the most effective tool for everything.

Has your writing changed since moving to America?

Because I feel free, the novel I am writing now is much more direct than my fables and very short stories. The novel is about the Syrian war; I’m going directly to the point, there is an immediacy. I don’t want to be symbolic in this novel. It goes directly to the Syrian disaster. Because there’s no chance to avoid it, or try and take more than one interpretation. There is something urgent.

I lost an unpublished novel in Syria, which was ready to be published in Arabic. When I left, I thought I would be able to go back-and-forth between here and Syria every two or three years. I left manuscripts, short stories, and poems, which were all ready to publish. It breaks my heart.

How does it feel to write after losing so much?

It feels very sad; I lost my apartment, I lost everything there. However, I always say to myself, “I am still alive, I’m still writing, I’m still thinking. I am very lucky in comparison to other people.” Look what’s happening with Syrian refugees. So, despite my loss, I’m so lucky. It is still unbelievable for me. Syria looks like hell now. I feel sorry for the people, the civilians, women, and children.

I find your stories easily sharable, do you ever think about how your stories could spread while you write them?

Maybe because they are quite short, many people have told me they are just like tweets. People can share them easily, and I like that. Many people ask me: “Why keep writing very short stories? Why don’t you write longer stories?” And I always say that to me these short stories are like a bullet. A very fast bullet. Give me your idea — and that’s it. I don’t want to keep on talking and talking for nothing. In my novel I keep talking.

Have you continued to write these stories in America? Or have you been mostly working on your novel?

Now I am working on the novel. It takes up almost all of my time. I’m not in a hurry with it. At the same time, I want to keep writing short stories, besides the novel.

You’re living in Pittsburgh now. How is that?

It is a great city, a wonderful place, with wonderful people. Finally I have peace of mind, because I was driving a cab in Chicago for over eight years. That was a serious hardship. I’m writing now; I’m a full-time writer, working on my new novel.

Do you go on a lot of walks?

When I was in Syria I was a very good walker. When I started driving cab in Chicago I forgot everything about walking, because I was driving seven days a week, sometimes 10 hours a day. Now in Pittsburgh I am walking everyday. In Pittsburgh now I am going back to my soul to myself. In Chicago, where I was driving a cab, I felt as if I lost myself. Now I am going back to Osama the writer. Writing is my blood, it’s my blood and my soul.