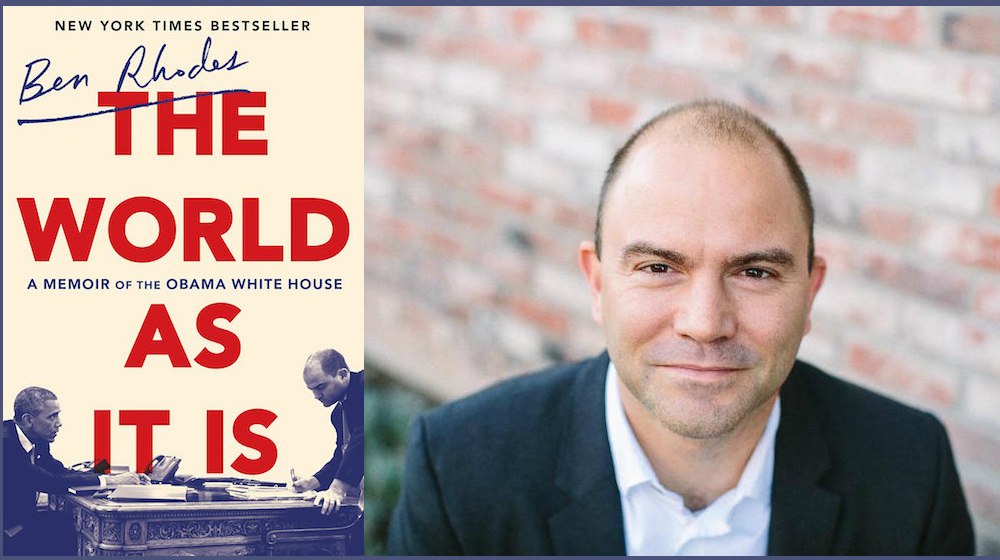

When did unspoken aspects of the Obama presidency eclipse anything that even this most eloquent of presidents could say? When did Obama’s conception of this presidency as a narrative or story most constructively incorporate implicit messaging and concrete policy-making? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Ben Rhodes. This present conversation (transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman) focuses on Rhodes’s The World As It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House. Rhodes is currently an NBC contributor, a contributor to Crooked Media, and the co-chair of National Security Action. From 2009 to 2017, he served as a Deputy National Security Advisor to President Obama. In that capacity, he participated in nearly all of President Obama’s key decisions, and oversaw the president’s national-security communications, speechwriting, public diplomacy, and global-engagement programming. He also secretly led negotiations with the Cuban government, resulting in the official effort to normalize relations between the United States and Cuba. Prior to joining the Obama administration, Rhodes received an MFA in fiction from New York University.

¤

ANDY FITCH: At one point you present yourself as a bridge between Obama’s speeches and his actions. And it seems crucial to your own narrative, but also to broader assessments of the Obama presidency, to think through the complex relations between prominent public speeches and the more mundane mechanics of policy implementation. So here we could start with any number of concrete scenes (with you, for example, preparing for the Berlin campaign speech by rereading and repeatedly listening to Kennedy and Reagan), and could ask what it means to craft a contemporary foreign-policy vision out from past rhetoric. We could consider Obama’s (and of course your own) more general efforts, both abroad and at home, to tell a coherent, constructive, self-reflective story (perhaps at times a new, or revised story) about who we are. We could begin tracing a personal arc that runs all the way to you drafting the public announcement of efforts to normalize relations with Cuba (where you say: “The words came easily; this was something I’d done, not just something I was writing about”). But could you start to address broader questions of how/when speech-writing (and speech-giving) shape the nuances of policy visions and their concrete real-life consequences, or how/when political rhetoric remains a sideshow on a separate plane from the real business of governance? Could you offer a couple different moments with different thresholds of when you are “just” writing a speech, and when your speech and Obama’s delivery of it are writing our collective history?

BEN RHODES: Let’s start with the Berlin example. My book quotes President Obama, on more than one occasion, telling me that our job consists in telling a really good story about America and who we are. Obama meant that, through our speeches, but also through our actions and policies, what we do has to add up to a coherent story conveying the best parts of America. We need to advance that story, and to go beyond wherever people have taken that story in the past. So if you look back at Kennedy and Reagan, you see their words spoken in Berlin offering a story of what the world wanted and needed America to be in those moments. Both Kennedy and Reagan connected with a historical moment when the United States had to represent the aspirations of people in many different parts of the world. And the office of the American presidency principally serves the American people, but also represents the most important political office to billions of people around the world. So in the Berlin speech, we wanted both to claim that mantle and to update the type of leadership and the set of values America brings to the world. We wanted to show that Barack Obama’s candidacy also represented its own distinctive form of historical progress, as the first African American with a serious shot at the presidency, and as someone emblematic of the previous social movements that had allowed him to reach this precipice. So you look back at words used by past American presidents, then you connect these to the very specific vision that Barack Obama brings to his campaign, and then, once you enter the Oval Office, those speeches take on far more real-world consequences — both setting a new direction and shaping policy.

The World as It Is describes President Obama, in his first year, giving a series of speeches at home and abroad expressing his broader worldview. At times, these speeches would butt up against past habits of the U.S. government. His speech at the National Archives early that first year gets significant resistance from within the government, for saying we had engaged in torture under the Bush administration. We also got significant resistance within the government for characterizing Guantanamo as a legal black hole. My book recounts the intelligence community inserting the comment that Guantanamo detainees have had more legal representation than any detainees in world history. So you start to feel this tension between where a president wants to lead us, and the ingrained habits or experiences of the U.S. government. Early in his presidency especially, Obama’s speeches offered one way to try to break through that tension, to signal a more definitive break with our past, to point both governmental policies and political discussions in a new direction.

Then Obama’s 2014 speech announcing the normalization of relations with Cuba, by contrast, brings a different set of consequences. Every word in that speech actively changes U.S.-Cuba policy. In that instance, Obama doesn’t simply offer a direction or communicate a worldview. He literally provides direction to the U.S. government and to the rest of the world about what our new policy approach will be. For 60 years, our entire Cuba policy had been predicated on attempts to isolate and squeeze the Cuban regime, to try to change it. But with this one announcement, Obama signals a complete reorientation of that policy, stressing efforts to open up relations with the Cuban government and Cuban people — as a more effective means of making change. People may not remember this speech as well as the Berlin or Cairo speeches, but, having done the negotiations leading up to this Cuba speech, I could feel tangibly how consequential its words were, completely in line with the actions we were taking. Suddenly, more Americans would be able to travel to Cuba. More Americans could do business in Cuba. Hopefully this all would bring about more economic opportunity and improve livelihoods for the Cuban people. So you have this feeling, in watching Obama speak these words, that lives will change, experiences will change, perceptions of the United States will change precisely because of what he’s saying.

For how this all contributes to the Obama presidency’s greater story, it still often startles me how much the management of a political leader’s public expression gets farmed out, and how even well-informed lay audiences typically do not recognize the extent to which this takes place, and how most politicos seem to think everybody realizes what’s happening. My own sense is that if you pressed most people to flesh out their conception of a political speechwriter, you would get something between a stenographer and a sophist — and that’s definitely not what this book offers. So here one question becomes: in what ways do you consider it socially useful (beyond you simply providing a personal record of your fascinating lived experience) for us to see, from the inside, the deliberative construction of Obama’s political messaging? Or how might it help our politics if larger audiences could conceive of a president like Obama (Trump is a different story) more as a decisive spokesperson for a complex institutional enterprise, and less as an almost mythic personal embodiment of the state?

Well I did want to convey the complexity of the role of the U.S. president. The president always has to be a distinct and decisive political figure with his/her own vision, while also executing the duties of an office that carries an enormous amount of institutional baggage, and taking into account an endless range of personal and administrative prerogatives. He/she has to communicate the formal position of the U.S. government on issues which often involve long-held policy approaches cutting across a diverse range of past administrations. Just to take a mundane example that no longer feels so mundane: the U.S. president needs to reaffirm our commitment to defend NATO allies when they’re attacked. These NATO allies need to receive that clear assurance from every single president. They base their entire security strategy on the United States providing this security guarantee. It may not seem all that dramatic to the American public for the U.S. president to stand up there and reaffirm our commitment to Article Five (the commitment to defend NATO allies). But as we’ve seen, when President Trump doesn’t do this, that upsets the equilibrium of how the whole world functions.

So even when presidents do not necessarily make new policy, you can draw a thread from their words to what ends up happening. I’ll go all the way back to that Berlin speech, when Senator Obama basically declares that, under his leadership, the United States will join the community of nations in trying to deal with the dangers of climate change. Nothing happens immediately, but you can draw a line from that 2008 speech all the way to the Paris Agreement reached in late 2015. It took first the United States shifting its official position on climate change, then seven years of negotiations and policy changes, before we could emerge in Paris with the global climate accord. So we do need to pay attention to the general direction that presidents set through their rhetoric, even when no immediate policy change occurs, because changes in rhetoric can foreshadow changes in prioritization that lead to changes in policy — which can lead to real consequences.

Writing this book also helped me realize how important those changes in policy become to you when you work in government. You want to see the work you’ve done, and the words the president has said, finally result in concrete recognizable achievements: like the Paris climate agreement, the Iran nuclear agreement, the opening to Cuba. You want to see these policies implemented in order to shape what the president’s successors will do. But you also need to see these policies implemented just to get a sense of perspective.

At the same time, putting this book together really clarified for me how the story the president tells impacts people’s lives in crucial ways you can’t anticipate. I thought back to presidents I had admired. I realized that for John F. Kennedy, who had been my political hero, I couldn’t give you a list of his top-ten accomplishments, but I could remember speeches I had heard or seen that changed my life, or that gave me a sense of inspiration and made me want to commit to some form of public service, whether or not in government. And then I thought about the billions of people who had heard or watched speeches by Barack Obama, and about what all those people would go on to do with their lives, and how they might trace certain decisions or accomplishments back to some germ of inspiration they took from something Barack Obama did or said or who he was. I sensed that the collective human reaction to what a transformative political figure says ultimately has a greater impact on the world than any policy you might put into place. That may sound lofty and ambitious, but I do consider it true for Obama, though probably not as much for every American president. With all due respect, I don’t think any particular speeches by Jimmy Carter or George H. W. Bush have that effect. But occasionally a leader’s legacy takes on a different shape over time, thanks to the impact of their words on a large cross-section of people in the U.S. and around the world.

Along those lines, we definitely could have a whole separate, more literary minded discussion of your book. On this topic of how subtle shifts in public rhetoric can reshape both long-term governmental actions and individual lives, for example, we could consider the whole complex parallel tension The World as It Is constructs between your own public writing and your private lived experiences. We could trace how your young writing life (the life of an NYU MFA student) gets eclipsed on September 11th, with that life quickly followed by a much more momentous life, a new life of writing in fact, and then with you gradually shifting from a focus on workplace writing responsibilities to workplace policy responsibilities, with your life itself increasingly becoming a public narrative, a part of history, and then with you finally taking a pause after this unanticipated eight-year whirlwind rushes by, to write about it all — and offering us, various references to government secrecy seem to hint, never the full story, at least a mildly elided fiction. Or for one single scene crystallizing many of these rhetorical complexities, I think of you narrating Obama’s delivery of the Hiroshima speech, with you sampling from that impressively intricate text, with you also stepping back at times to provide a palpable sense of how it feels and what it means for Obama to deliver this speech in this particular setting, with you rewriting that moment as part of his, and our, and the world’s narrative. And I mention all of that just to make clear how this book’s layered explorations of where “writing” and “action” happen merit reflective discussion on literary grounds, not just on real-time-chronologies-of-the-Obama-administration grounds. So before we do have to shift back to questions about the Obama administration, do you want to describe at all how you went about finding a literary form that might adequately reflect this narrative “I’s” ongoing search for some sense of identity amid the executive “machinery”?

When I set out to write the book, I quickly realized that I didn’t really like the genre of political memoir [Laughter]. These books can feel like exercises in the recitations of past conversations, positions, arguments, like: “Here’s why I was correct in that meeting,” or “Here’s somebody I want to settle the score with.” So I tried to find a different entry point for this book. And that entry point eventually came from me, as a generally anonymous 29-year-old with relatively little life experience, first beginning to work for the Obama campaign, then gradually emerging as one of this pivotal U.S. president’s closest advisors and confidantes. I thought I could do a couple of things with that particular narrative arc. I could allow the reader to enter this experience of working for an American president, for Barack Obama, through my experience — because I could be recognizable to a reader. Everybody’s been…

Or still might become.

a 29-year-old who doesn’t quite know their place in the world, trying to make a meaningful difference but unsure how to do it, or whether they even can do it. Therefore, in the tradition of both novels and memoirs, this “I” can be an everyman-type of character, taking readers along on this journey and experience. And I also realized that if I worked to bring my personal life into this story (my private relationships but also my personal doubts, misgivings, the highs and the lows), I could illuminate what it feels like for a human being to be transformed by this enormous experience. And hopefully, along the way, I could also help explain, essentially, this broader enterprise of the U.S. government.

I’ve always liked literature that wrestles with an individual interacting with a system. I read a number of very helpful models as I thought through this memoir, and how I didn’t necessarily want to fulfil the template of typical political memoirs. Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker, for example, presents this narrative about a twenty-something entering into a much large enterprise (in that case, Wall Street and Solomon Brothers), bringing with him a whole set of expectations, but then all of those expectations change as he learns more about the system he has joined. Lewis balances really well an explanation of how this system works, and an explication of how this character feels about it as an individual.

Another more recent model came from Hisham Matar’s The Return, an amazing memoir from last year about this individual whose father (a leading oppositionist against Qaddafi) had been disappeared when Matar was a child. The book details Matar’s return to Libya in the midst of the Libyan revolution, to find out what happened to his father. The Return gave me another fascinating model of how it feels for an individual when their life suddenly gets shaped by historical forces beyond their control. Matar of course went through a much more dramatic experience than mine, with the disappearance of a parent, but his book’s basic theme still felt similar to what I wanted to explore. I also of course found it fascinating to read this intimate first-hand account of the Libyan intervention, which I knew I would write about from a foreign-policy perspective.

And I also should mention here David Halberstam’s The Best and the Brightest, where Halberstam somehow illustrates these complex policy processes and debates related to the Vietnam War, again through his vivid account of individual characters. The Best and the Brightest really helped me think through how to present my book’s many characters…not just me and Obama, but how, in fairly limited space, do I humanize people who the public, in many cases, already feels familiar with? Halberstam puts an enormous amount of work into making public figures three dimensional on the page. I read his book thinking about how I could tell a good story that sometimes can represent a fairly dry policy process, while still making the supporting characters real, distinct, memorable.

On this topic of how it feels for an individual human to be transformed by some much greater enterprise, we get a lot on you trying to understand your place within the Obama presidency. And this opens up, for me at least, parallel questions about Obama’s own lived self-scrutiny of his place within the Obama presidency — again with, as you note, millions of individuals around the world lined up to watch his motorcade pass by, and with (perhaps most importantly in this book) Obama’s embodied (inevitably racialized) presence often taking precedence in public and even in many private political contexts, over anything he ever could say. Here could you articulate a bit your own “gift and…struggle” of writing for a figure whose spoken words often will not match the emotive power manifest in the dramatic image of this particular man delivering them? And here I won’t ask you to describe what it felt like for Obama himself (one of the smartest, most reflective, most eloquent persons one ever could imagine inhabiting the presidency) to perform this role. I simply find it worth noting that this book which so extensively recounts the writing of the Obama presidency puts so much weight on the unsaid, and I start wondering how the unsaid factors into what you have described as this broader story that the Obama presidency tells.

That’s a great way of putting it. First I probably should describe the realization that occurred to me in the ‘08 campaign. As much as I labored over every word and felt that these words could connect with an audience, could make a difference in the campaign, could even redirect history, I gradually realized that the fact of an African American delivering those words and potentially occupying the position of the presidency was more important. This realization hit me in Berlin. I recognized that the fact of Obama standing before 250,000 Germans, channeling American values and offering a vision for American foreign policy, would mean much more to his audience than any specific words he said. In my mind I made a direct analogy to Jackie Robinson, in the sense of Obama playing on that high-profile stage and carrying himself with such dignity, refusing to let the opposition (some of it clearly rooted in racism) rattle him. He could demonstrate that this highest of offices should be accessible to everybody — not just to black people, but to minorities in general.

And of course this racial dynamic of the Obama presidency become all the more pronounced (but also harder to talk about) throughout his presidency, as it became increasingly apparent how much the fervor and opposition to Obama was rooted in race. Writing this book and reliving those experiences, I realized that the greatest upticks in hatred for Obama came when he succeeded: when he executed a successful foreign campaign trip, when he got elected, when he navigated the financial crisis, when he passed health care. Sure, some of that opposition just came from people with different political views, but I profoundly do not believe that the Tea Party movement came from some people getting mad about the deficit. I still find it chilling that what most threatened a certain segment of white Americans was in fact Obama succeeding. If Obama had fallen flat on his face, and had been a terrible president, some Americans would have found him far less threatening, because those failures would have validated a certain view of white supremacy.

I also want to mention here how Obama did deal with racism. He came to realize that just doing his job extremely well would mean a lot, without necessarily talking about race so much. He had one early pivotal moment when Henry Louis Gates, Jr. got arrested at his home in Cambridge, and Obama said the cop had acted “stupidly.” Days of debate followed about this comment, until we had to have this hokey beer summit with the cop, Gates, and Obama. I think Obama realized in that moment that basically anything he wanted to accomplish would get subsumed (by a useless public discussion, frankly) each time he talked more directly about race. If I’m Obama, and I give an interview about healthcare because I want people to understand my healthcare policy, and if I say anything about race, nobody pays any attention to what I say about healthcare.

But race would come up in more private moments. We would discuss what Obama should say if asked whether his opposition was rooted in race, and he’d offer: “Yes, of course it is. Next question.” Or someone would ask in private “How should we deal with the tensions created by the Black Lives Matter movement?” and he’d say: “Well, cops should stop shooting unarmed black kids.” Again, we knew he wouldn’t really answer in public like that. This was his ironic way to acknowledge that we all understand what this is really about, even if we don’t directly say it.

And it did feel very strange to be this white man writing the words a black man would speak, without me having any knowledge of how it really feels to be African American. I remember having to tell Obama that Nelson Mandela had died, and realizing that I would have to write the eulogy. I wanted a feel-good moment like in the movie Invictus, with Obama flying to South Africa to tell us the world’s a better place because Nelson Mandela won in the end. Frankly, that’s a message designed to make white people feel good, and doesn’t accurately reflect the experience of Mandela, or Obama, or Africans, or African Americans. But Obama ended up writing his own quite personal speech about Mandela, lifting up Mandela but also recognizing his imperfections, not presenting Mandela as some saint or some figure destined to have a happy ending to his story — but instead as somebody who at times had engaged in violent struggle, yet who also had made Obama himself want to become a better man. I found it especially moving that Obama didn’t say “He made me want to be a better political leader,” that Mandela’s ability both to accomplish what he accomplished and to be a real human was what made Obama want to be a better man.

Back home, the lead story about Barack Obama’s attendance (the first African American president attending the funeral of the first black African president of South Africa) focused on a selfie that the attractive, white Danish prime minister took with Obama. He couldn’t believe it. He told me the U.S. media had never upset him so much, and had never before made it so clear how racism continues on long after the election of Nelson Mandela or Barack Obama.

This reminds me of the series of long interviews with Ta-Nehisi Coates at the end of Obama’s presidency, which openly acknowledged their competing perspectives. You could describe Coates either as more pessimistic or more realistic about the lack of racial progress we have made in the United States. Obama tries to offer a more optimistic view of how far we have come in the past 50 years. But in private Obama also made it clear that the supposed difference between his perspective and Coates’s mostly reflected their different vocations. Coates, as a writer, had a duty to look squarely at the hardest truths and expose them. Obama, as a political leader, needed to point people in a positive and optimistic direction. If Obama had given up his optimism, he couldn’t have functioned as a political leader. But that doesn’t mean Obama wasn’t acutely aware of all of the historical and social and political forces that Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about.

And in my own way, I wanted to make sure that this book, without getting heavy-handed, made perfectly clear that we saw the whole time how racism drove the Sarah Palin phenomenon, the Tea Party, the Birther movement. Even Benghazi discussions, to a certain extent, directly reflected these highly racialized elements. You can’t understand the opposition Obama faced and the election of Donald Trump if you don’t include racism as a primary factor in that story.

But here again I also had to do some self-reflection about being one of those white people who wanted a Barack Obama presidency to redeem my country’s story. Often the words of Obama’s white speechwriters probably tilted in this direction. Frankly, Obama himself had to reign in some of our more unbridled optimism. This led to an interesting hybrid rhetoric, where you had, in the words he spoke, both the struggles of an African American and the misplaced optimism of the white people working for him — all coming together into one narrative at the epicenter of the Obama presidency. Of course you didn’t need to ask African Americans whether race factored into the opposition Obama faced. Pretty healthy majorities would almost roll their eyes at that question, would put much less credence into this notion that Trump’s support just comes out of people feeling economic anxiety (whereas white people would probably give a much more diverse set of answers).

I do think that your book does a great job articulating how largely unspoken elements of Obama’s public persona work, at their best, to tell a new story of American exceptionalism, of an exceptionalism that derives not from obscuring, ignoring, denying our fundamentally flawed past, but from embracing and even celebrating our capacity for self-correction. So here again, could you describe any particular moments that helped clarify for you the intense emotional registers at play (of course both positive and negative emotional registers, depending on one’s perspective) as various audiences, at whatever remove, absorbed the implicit (as much as explicit) political messaging? And if we can agree upon these perhaps unspoken yet powerful rhetorical forces emerging through Obama’s dignified embodiment of the presidential office, would it be contradictory for this administration to respond to conservatives or to populists: “Hey, what are you getting so worked up about? We’re pragmatic policy people. We didn’t say anything to arouse those passions”? Or another way to put this: did your own reflections putting together this book make it all the more clear that it would be naive to think that Obama could generate such idealizing enthusiasms in 2008 without (basically in the same moment) generating the panicked tribalist resistance of 2010 and 2016 — that whether or not Obama directly addressed race at any given moment, race became, on both sides, a driving force shaping the public’s response?

Well I have found it interesting how much the reaction to this book has focused on one scene after the election, when Obama, in the presidential limousine, asks me: “What if we were wrong? What if people just want to fall back into their tribe? What if we pushed too far?” I wrote that scene first. It comes at the book’s beginning, and I wrote this book largely to answer those questions. And I’ve had a hard time with them. Looking back, I can see more clearly that the Obama presidency stirred up this backlash creating an opening for a racist demagogue like Donald Trump to get elected. I still would note layers of complexity to this situation, including the fact that Obama almost certainly would have won in 2016, had he run again. So, strangely, we seem to have lived through a reaction to Obama, but never a rejection of Obama. He never lost while running for president. So that leaves a certain ambiguity about whether or not this backlash inevitably had to succeed.

In reliving that whole experience, I kept returning to this line I emailed to Obama on the night of the 2016 election, and which Obama himself then seized on in public: “History doesn’t move in a straight line. It zigs and zags.” Of course this doesn’t really answer the question. But all that you can do depends on what you can control, and I really don’t know what we could have done differently to mitigate the backlash. Obama was such a dignified presence — again not a perfect guy, but obviously no radical, obviously not a polarizing personality. Sure, he had more liberal policies than some Democrats. But again, I don’t think our healthcare plan explains the extent of this backlash against him. What was polarizing about him was just the fact that he was black. I still see us as working through this complex set of cultural issues as a country, with Obama representing a significant leap forward, while Donald Trump represents history’s zig and zag moving backwards. Ultimately, if this story continues to progress, history will record that the Obama presidency offered one more solid step forward. And not to get too historical here, but every significant gain for African Americans (whether after the Civil War, or after the Civil Rights Movement) has been followed by a step back. But then that step back itself gets corrected, and things continue to move forward.

So my basic answer is: “No, we weren’t wrong.” We still face this backlash, but that doesn’t somehow invalidate what we accomplished. If you decide that Obama being president will overwhelm some people, and provoke resistance, so we shouldn’t even try it in the first place, then we’ll never move forward. In this world as it is, we have to recognize that not every narrative has a clean and happy ending, but that this doesn’t mean we somehow took the wrong direction, or that we have no chance of still emerging on the other side in a better place. This book’s very title comes from Obama’s rhetorical turn that you have to see the world as it is in order to pursue the world as it ought to be. I wanted this book to present a clear-minded recognition of the backlash engendered by the Obama presidency, without in any way apologizing for the fact of the Obama presidency or the things he did.

Yeah, just to clarify, I don’t question at all whether Obama should have pushed for center-left policies, or whether electing an African American president has helped America to move forward in some ways. I just mean to ask: retrospectively, at least, should the (ethically indefensible, racially charged) partisan resistance to Obama not come as a surprise, as if tribalized politics hadn’t been in play from the start? Or here in terms of present-day political partisanship feeling so stifling for you, for Obama, could we pivot to your book’s broader claim that if the Obama administration faced the kinds of opposition parties that Lyndon Johnson or Ronald Reagan faced, Obama could have reformed our tax code and rebuilt our infrastructure? I don’t doubt your point. I see how problematic it is for our long-term future that those developments didn’t take place. But I can’t help sticking on the thought: True, but eras that elect a Johnson or a Reagan wouldn’t elect an Obama — and not just because of race. Here I turn, for example, to political theorist Frances Lee’s arguments that we might need to differentiate more clearly between the obvious symptoms and the underlying causes of present-day political polarization — that, for example, historical stretches in which changes in power remain ever-present possibilities are perhaps inevitably (regardless of whether Mitch McConnell runs the Senate) eras of hyper-polarization: with neither party forgetting for an instant their foundational concern with winning the next election cycle, and with the office of the president perhaps inevitably the primary source and target of polarizing antagonisms (in large part, again, due to public conflations of presidential rhetoric and governmental policy). Within that interpretive context (with which you can agree or disagree as you see fit), what advice would you have for future presidents and administrations of “change,” on needing to presume, from the start, the likelihood of encountering the strongest possible dysfunctional partisan resistance — particularly from displaced constituencies resenting the changes you have brought, and sensing that an era of change might soon in fact bring these more retrograde forces themselves back to power? How could/should progressive “change” administrations most effectively anticipate, cope with, push back against, somehow short-circuit or overcome such seemingly inevitable (in these moments) partisan tendencies, rather than getting blindsided by them, or mad about them — rather than getting tied up in taking them personally, and blaming that damn opposition party?

The premise of that question sounds right to me. The 2008 election landslide, the biggest Democratic landslide since L.B.J., gave us a 60-seat Senate supermajority, and presented an existential threat to Republicans. If that political dynamic worked well enough for most Americans, Republicans would find themselves lost in the wilderness for a long time to come. So they had to do everything they could to create the perception that whatever we did was failing. That explains Mitch McConnell.

And on the 2008 campaign trail, a new dynamic had literally opened a window onto future messaging technologies — with forwarded emails getting such a wide traction, especially those saying something like: “Obama not born in America,” or “Obama a Muslim.” We actually had to start giving field organizers talking points to rebut these claims. And then with Sarah Palin’s nomination for vice president, this whole subterranean force suddenly got mainstreamed in Republican politics. By the 2010 midterms, that force had become the Republican Party’s driving energy. All of which is to say that McConnell’s obstructionism, whether or not a rational choice, still had the deeply problematic effect of subsuming the Republican Party into the darkest elements of its base. I still consider that the strangest part of this whole dynamic — that a Washington-based obstruction strategy helped birth the grassroots emergence of a new brand of demagoguery which then again evolved with Trump.

So in terms of what we could have done differently, I do start from one of the Obama presidency’s major ironies: that the last two years, when Obama pushed the most unabashedly progressive agenda, was when he was most popular. I still haven’t fully worked though the implications of that fact. At the outset, he really tried to compromise. I can’t see somebody arguing today that Obama should have tried more to compromise. He really did. He directed a third of the stimulus to tax cuts, which he definitely wouldn’t have done if trying just for Democratic votes. But it didn’t matter. Republicans didn’t care. Similarly, the healthcare plan Obama called for was not single-payer. Obama basically called for a Republican plan. He tried to use conservative ideas to achieve progressive ends, and that didn’t really work politically.

But then, by 2014, after those midterms, Obama clearly decided that he had just had enough, and was going to be himself. Within a period of weeks, we had the announcements to protect the DREAMers and their families. We had the Cuba opening. We had the deal with China on climate change that led to the Paris accords. That compressed period of activity set the tone for the next two years, which also included the full embrace of gay marriage in our country, as well as the Iran nuclear deal. And I don’t believe that those two especially productive years led to Trump. The Republicans already had gotten to the point where Trump was their most natural candidate, whereas the fact of Obama having a 60% approval rating at his presidency’s end (even before the 2016 election) demonstrates how being fully himself had resonated with the American people. So here I draw the lesson that when Obama’s words and actions fully reflected what people could sense were his authentic beliefs, people responded much more enthusiastically. When Obama seemed much more ambivalent and stuck, in 2011 for instance, trying to negotiate something he didn’t really believe in, with Republicans who showed little interest in negotiating with him anyway (even over issues like the debt ceiling), the public sensed that ambivalence, and Obama’s approval ratings went down. So I’ve come to the conclusion that leaders need to use their time in the most authentic and genuine way, to pursue the ends they really believe in. The public picks up on this. Frankly, I don’t think Hillary Clinton conveyed that level of authenticity, in part because conservatives and the press already had caricatured her for so long.

And this authenticity dynamic ultimately explains a lot of the 2016 election. Trump, for all of his many flaws, seemed authentically Trump. So I feel like I’ve given a completely counterintuitive answer. People might expect me to say: “The president should try to work more with Congress,” or have Congress in for drinks and things like that. Sure, you should try to do that — but being yourself, and working on issues you care about, ultimately will make you a more attractive politician to the public, and your fellow politicians in turn will react to the public.

Well you also hinted, at this conversation’s start, that an administration’s persuasive narrative for the public does involve concrete actions too. And here it sounds like the rhetoric and the policy really came together in Obama’s last two years, further confirming this idea that the story politicians or administrations tell is not just a rhetorical story (even with rhetoric an essential part of that story). But now pivoting back to Obama’s own most distinctive and authentic rhetoric, it also struck me, reading over his speeches from the past decade, to see them drawing, for example, on his childhood experiences in Indonesia in order to make universal claims about broader human values. Or again, in the Cuba speech, Obama has the moral stature to make the claim that certain rights are universal rights, everybody’s rights. From my position more in intellectual and artistic circles than political circles, I find it hard to picture future progressive-identified Democrats being able to make such universalizing claims (at least without adding a long list of semi-apologetic caveats and qualifications) without facing significant skepticism from certain vocal elements of their base. Or conversely, in terms of Obama’s “Maybe people just want to fall back into their tribe” lament, I couldn’t help thinking of Amy Chua’s recent Political Tribes book, and her concern that when progressives seek to stamp out tribal identifications they distrust (say in relation to patriotism), this can create stifling cultural vacuums for huge portions of the population, subsequently exploited by demagogues like Trump — so that just stitching back together the basic Democratic coalition becomes this apparently major accomplishment, before even appealing to any other voters. So what deft political maneuvering around tribal pressures might get more of us to feel committed to a constructive, inclusive, collective national or even cosmopolitan (hopefully progressive-minded) tribe?

That’s a really good question. First I’d say that progressives (certainly myself included) made the mistake of seeing progress as somehow inexorable, of assuming our society will just keep getting more and more inclusive — that history inevitably will progress like this. That presumption rubs many people the wrong way. And it fascinated me while writing this book to think through interconnections between a broad range of tribalists. I quote Obama recounting a 2014 discussion with Estonia’s president, who had described how ISIS and Putin both represent different elements of tribalism — with Putin’s desire to fall back on Russia’s past greatness echoing ISIS’s desire to re-establish the caliphate. And Obama responded: “Yes, I know about the forces of tribalism. I’ve been dealing with them my whole presidency.” The Tea Party (like people embracing a fundamentalist view of Islam, like Putin reclaiming Tsarist Russia’s glory, like Brexit advocates wanting to abandon the European Union, like Trump supporters wanting to make American great again) all express (obviously with ISIS acting the most violently) the desire, in the face of globalization, in the face of the migrations of peoples and the blending of cultures, to fall back on a more familiar world, a world that is in fact slipping away.

But again progressives make a mistake when they just assume that the rightness of their worldview will somehow overcome this reality. I think Obama tried (and frankly, this makes Obama much more successful than most progressive politicians in the United States) to make his progressive message profoundly patriotic. The irony of the “Apology Tour” critique is that if you read Obama’s speeches today, they come across as more patriotic than any American political leader’s at least since Reagan. But their patriotism involves telling a progressive story — a story in which we can overcome things because we’re American, in which we strive to keep perfecting our democracy because we’re America. His Selma speech perfectly distills this worldview; it’s a speech about American greatness, but with Sojourner Truth and Jackie Robinson as its heroes.

If you try to tell some empty story about universalism, you’ll fail, whereas if you frame your story about values within the story of our community or nation, you’ll reach more people. You won’t reach everybody, but you’ll reach many more. And again, at his most skillful as a politician, Obama could take the message of universal values and progress, but anchor this in an American experience, in ways that made it more accessible to people. That’s really hard to do, but I think we draw the wrong lesson if we conclude that progressives have to conceal what we believe, or to purge any trace of patriotism — in order to appeal to specific tribes. Again that makes a politician come across as inauthentic. People won’t respond to that person. If you look at Barack Obama, Justin Trudeau, and Emmanuel Macron, they figured out how to make the broader case for patriotism, and won. Progressives who lose elections often can’t figure out how to do this.

In terms of the world as it is, and in classic realist “great game” fashion, Russia in fact looms increasingly large as this book closes. I appreciate your incisive accounts of Republican leaders, prior to Trump, already finding something to admire in white, patriarchal, anti-globalist, authoritarian-tending Putin, or your comparisons of U.S. communications operating, by analogy, at the pace of print media (still bound to fact-based norms) versus Russia’s viral spread. I find myself maybe as disturbed as you did by the moment when you worry about Russia launching a personalized disinformation campaign against you — and then realize that every global political figure probably now experiences this same fear every time he/she contemplates criticizing Russia. I noted one particular line, though, that really gave me pause, when you mention the Obama administration refraining from retaliating against Russian manipulation until after the election, “assessing that anything before could have led them to hack the election itself.” Does this statement acknowledge that the Russians did and do have the capacity to quite directly hack our ballot results (a capacity I mostly have seen both the Obama and Trump administrations deny that they have)? And if you believe that the Russians have this capacity, do you really believe that they would hold back on deploying it unless they were sufficiently mad at us?

I’m no cyber expert. But I assume, based on everything I know, that of course they have this capacity. If they deployed the full weight of their cyber capabilities, I assume they could shut down our power grid. So you have to assume they could shut down some voting machines. Again I don’t say that with any confidential background knowledge. I just think this speaks to the complexity of how we often make foreign-policy and national-security decisions. You have to calculate that if you punch somebody, they very well may punch back. But if you don’t punch them, then they may feel like they’ve gotten away with something. That inherent tension shapes any decision about whether to take aggressive action against a foreign power.

But in part I do want this book to convey about Russia (and about a lot of decisions) that I don’t know when we were right or wrong. If someone says “You should have just launched an offensive cyber operation against Russia, and that would have changed everything,” I don’t know if I believe that. But I don’t know if we made all the right calls either. Clearly, the outcome suggests that we didn’t.

But you have to keep in mind that we found ourselves in totally new territory. I wanted to convey that strangeness of being in government and confronting something completely new, with no playbook. We never had faced this experience of a foreign power deploying a whole set of tools to impact our election. Just to take the fake-news information war that Russia waged: I wanted to convey to readers that no tool existed to stop that. The Internet is open. If someone in a foreign country creates a mass volume of inaccurate and extremely negative news about Hillary Clinton, and shoots that into the social-media feeds of tens of millions of Americans, we cannot stop them, unless we start censoring everybody’s Facebook feeds. Part of what I find especially worrying about what happened and what could happen again is that neither we nor our technology and media companies have developed a set of defensive measures to prevent the type of assault you describe from happening. The Obama administration essentially had to wrestle with this new phenomenon in real time. And in retrospect, I can see certain ways in which we responded by reverting to the familiar. We do know how to stop cyber attacks. We do know how to try to protect ballot machines from manipulation. We do know how to say: “We can attribute this cyber attack on the DNC to Russia.” But we don’t know how to prevent the creation and dissemination of fake news. So the government did what it knew how to do, but didn’t do what it didn’t know how to do.

You basically could boil down all of these concerns, and any shortcomings in our response, to the question: “Well, should Obama have talked about all of this in public more?” I consider that a totally fair question. Maybe we should have provided more context for people about what we thought we saw happening. We probably should have. And of course the chilling outcome was that just as we really began to get our minds around the scale and complexity of what Russia had done in our election, we were walking out the door and handing over power to the very people Russia had deployed those tools to put into office.

Yeah, and just to clarify, my question probably comes out of the Obama administration, in the two weeks leading up to the election, offering these totally weak arguments for why Russia couldn’t hack our ballot results. Officials would say: “Well, we have 50 states all operating their own separate election processes, so it’s really hard to hack our national election” — as if Russia needed to do anything more than hack a couple machines in a few select, overburdened, already (often thanks to Republican voter suppression) underfunded precincts.

In retrospect, staff were so panicked that the election result itself could be thrown into doubt, sparking a really significant political crisis, that we felt this bias towards trying to reassure people. In retrospect, that might have been misplaced.

Finally, when this book’s narrative arc winds down with the warning (passed on from the guy who carries the nuclear codes) that you’ve run on stress and adrenaline for close to a decade, and now will need to adjust to a different pace, I wonder if that sort of transition would have been helpful to make years earlier. I sense a bit of cultish veneration for the chronically sleep-deprived staffer in here. And maybe you can just call me naïve and obliviously removed, but when you write, say, of the president’s daily briefings so rarely tracing long-term trends of social/governmental/ecological well-being (instead mostly cramming in potential foreign-policy crises and terrorist plots), when you lament that non-urgent but morally pressing foreign-policy issues (say our decades-long failure to address the legacy of unexploded U.S. munitions in Laos) forever get short shrift as ranking officials reel from one emergency and/or communications flare-up to the next, when you describe John Kerry and Ernest Moniz haggling with their Iranian counterparts for 13 straight insomniac days and nights, I do ask myself when the siege mentality your book’s second half increasingly evokes comes about due to some self-imposed, zombie-like state. And maybe getting enough sleep is a dumb point of focus here, but do you consider your book to make an argument, to register a potential criticism, when you so consistently return to scattered reflection on how your governmental assignments have distanced you from typical human intimacies — or are these just daily documentary dispatches, with no specific agenda attached? Or alternately, think-tank culture offers one professional path you did not take, but since, throughout this narrative, you persistently present yourself as starved for more time, for more intellectual and analytical and cross-cultural clarity, for more informed and reflective perspectives, could you describe your post-administration conception of what the most dynamic or productive relation between think-tank culture and policy implementation might be? Or most broadly, where do you now, looking back, see moments when the world as it was for you didn’t necessarily have to go this one ruthless way? What types of personal agency would you like, say, a subsequent political adviser to find in this particular world, that you maybe couldn’t find amid the endless improvisation for this first immersive portfolio of yours?

This will sound like a tangent, but it will get us there. A well-known American journalist friend of mine, who covered our White House the first couple years and then went to London to run a bureau, has described being most struck by the fact that, if anything significant happens around the world, the American news story starts off by asking “What does this mean for Obama? What will Obama do about it?” whereas, in London, the story starts off: “This thing happened.” The next couple paragraphs continue: “Here’s what this thing that happened means.” Then maybe, in the middle of the story, you get: “What can the U.K. and the U.S. and others do about it?” Our politics and our media have created this strange dynamic in which we act as if the U.S. president is responsible for everything in the world. That distorts policy. That distorts our understanding, particularly about things that happen beyond our control. Not for everything, but for some things, we just can’t do much about them.

And you’re right to link this dynamic to the daily presidential briefing and the daily press briefing often just reacting to some event. And so much of what think tanks do is to develop interventionist policy responses for whatever is happening. So again you find an underlying presumption that every problem has a solution, and that the American president should provide those solutions. If you allow yourself to fall into that trap, not only will you need to work 24 hours a day, but you probably won’t accomplish very much. But gradually, later in the presidency, I realized that if you free yourself from this burden, you actually have tremendous agency. If I can say: “I’m going to spend the next year and a half of this job carving out time to fly to Canada, and Trinidad, and Mexico, and Cuba, to meet with Cubans and negotiate a normalization of relations between the United States and Cuba,” then I can accomplish something very significant. If I just spent that time in meetings reacting to whatever new crisis occurred in the Middle East that day, I probably wouldn’t accomplish much at all. So that speaks to the need for some personal discipline in these offices, to ensure you don’t just react to events, to identify where you do have agency. You have agency to build an agreement with 200 countries to fight climate change, or to reinvent our relationship with Iran, but only if you don’t keep chasing every single soccer ball. You have to stay poised and say: “We also need to focus on the issues and opportunities where we have real agency.”