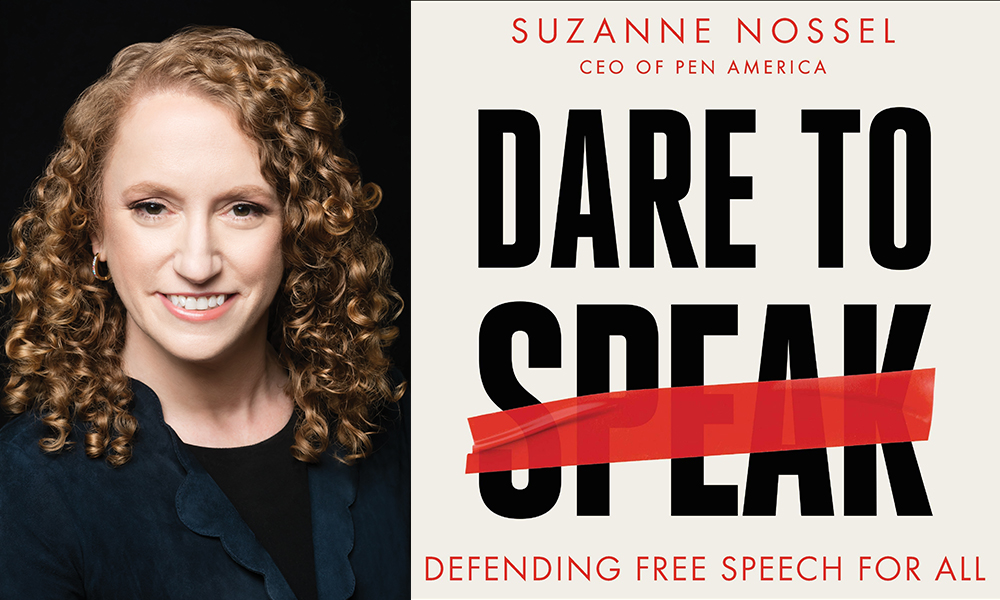

When does a robust defense of free speech demand that we push back against harmful speech? When does protecting free speech mean ensuring access and opportunity? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Suzanne Nossel. This present conversation focuses on Nossel’s book Dare to Speak: Defending Free Speech for All. Nossel is Chief Executive Officer at PEN America. Prior to joining PEN America, Nossel served as the Chief Operating Officer of Human Rights Watch, and as Executive Director of Amnesty International USA. She has served in the Obama Administration as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for International Organizations (leading US engagement in the UN, and in multilateral institutions, on human-right issues), and in the Clinton Administration as Deputy to the US Ambassador for UN Management and Reform. Nossel coined the term “Smart Power,” the title of a 2004 article she published in Foreign Affairs. She is a featured columnist for Foreign Policy.

¤

ANDY FITCH: First, for more or less any liberal society, at any time and place, how does free speech operate as a foundation for all other rights? And how might it serve as a (sometimes overlooked) catalyst for countless aspects of improved individual and collective well-being?

SUZANNE NOSSEL: Right. Our free-speech debates don’t acknowledge these basic benefits as much as they should. So I often frame free speech as underpinning many other rights. In times of significant social change, for example (whether through the women’s-rights movement, the civil-rights movement, the movement for LGBT rights, for immigrants’ rights, for environmental justice), participants have depended on this ability to demonstrate, to work with the press, to amass popular support, to petition the government and advance their causes. Without the protections that make this all possible today, an emerging movement could be hobbled before it gained steam. US history has many examples when the leadership of vibrant local movements would get arrested, preventing those movements from getting further off the ground.

I also describe free speech as an underrecognized catalyst for widespread social progress. Modern society needs to debate new ideas, hear from different perspectives, allow for dissent and the toppling of inherited orthodoxies, enable new voices to gain ground, and to examine skeptically the prerogatives of government and other power structures. That’s how progress moves forward on a whole host of issues: how we improve social well-being, push for greater democratic participation, and achieve enhanced equality. I see our social-justice movements and our Constitutional protections around free speech as intimately intertwined.

So for perhaps the most pressing free-speech debates in present-day America, could you say more about why we need to see fights against discrimination and bigotry not as coming at the expense of free speech, but as essential and mutually enhancing complements to free speech? How have free-speech norms themselves reinforced social inequities at times? And how should we think about rectifying those concerns without categorically dismissing free speech as a playground for privileged groups? What can it look like today to operate as an anti-racist free-speech advocate?

Well that timely question speaks to topics we discuss constantly at PEN America. PEN America has a dual mission — working persistently to defend free speech, and to dispel various forms of bigotry. We have committed ourselves to that mission ever since adopting the PEN Charter in 1948. So while certain activists on either side may see these two basic principles as pitted against each other, and while of course tensions sometimes do arise, we at PEN America consider it critically important to build on both sets of values, and to see them as mutually reinforcing components of a vibrant democracy.

Specifically in terms of taking an anti-racist approach, I think free-speech advocates need to do a much better job of acknowledging the real harm that speech can cause. Free-speech advocates often hesitate here, worried that when you point to those harms, you open the door to censorship — that if you concede speech can cause damage, then this strengthens the argument for banning or suppressing it. Free-speech advocates have a tendency to talk more about how the harms of speech can be overblown (a valid concern), but sometimes at the expense of genuinely acknowledging that they exist and can be serious. So I see this differently. I consider it just basically disingenuous to ignore or dismiss the reality of certain speech causing harm. I devote a chapter in the book to these harms, and to research that substantiates them.

I also consider it vital to create space for deliberative conversation where we can recognize that sometimes these harms are exaggerated — or, even more worryingly, overstated as a rationale to suppress speech (less because it’s harmful than because it’s disagreeable or disfavored). Again this doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t recognize, assess, and address speech’s harms. In my view, a robust defense of free speech in fact demands that we push back against noxious expression, that we call out hateful speech, and that we actively work to prevent hate crimes. I devote another chapter in the book to what free-speech advocates can be doing on those fronts. PEN America, for example, has a program devoted to combatting online harassment, much of which is targeted on the basis of gender, race, and other protected characteristics. Only by helping to mitigate these harms of speech can we make a coherent and convincing case about the crucial place of free speech within a more equal and inclusive and just society.

Still in terms of a distinctly American approach, the First Amendment often gets read as establishing negative rights, protecting us from government infringement on individual expression. But possessing capacities to contribute to the public discourse also suggests forms of positive freedom — proactively nurtured by a society that provides adequate education and opportunity to every individual, and that builds and maintains a cultural/institutional infrastructure for constructive civic exchange. So where do we and don’t we need our American government to enshrine and ensure robust free speech?

Traditional free-speech advocacy does tend to focus on fighting back against government encroachments, and defending the First Amendment. Those always will remain very important projects. But again, when we acknowledge the critical role that free speech plays in separating truth from falsehood, promoting wellsprings of new ideas and creativity, helping us to make necessary course corrections and to collectively envision whole new future horizons — that all obligates us to support free speech in a much more proactive way.

For contemporary America, promoting robust free speech starts by recognizing that such rights can’t be exercised equally or fruitfully in a society beset by systemic racism and other structural inequalities. When groups get excluded from educational opportunities, from economic opportunities, from professional opportunities, from platforms for speaking out (in journalism, or publishing, or Hollywood, or on-air), free speech cannot flourish. With all of these perspectives missing from the picture, the most crucial or compelling or productive ideas and opinions have a much harder time rising to the foreground, and the marketplace of ideas is impoverished. So in my view, defending free speech also means picking up the obligation to dismantle barriers to participation and opportunity — enabling and encouraging many more voices to be heard.

Yeah, Dare to Speak’s introduction emphasizes individuals operating as self-regulating guardians of free speech. But you also acknowledge throughout this book “how advantage and disadvantage affect attention and shape discourse.” Here again questions of scale come up for me: in terms of speech’s relation to identity, access, power. So could you sketch a continuum, say from the most personal gestures to the broadest social structures or platforms, on which you see the need for updated commitments establishing an enabling environment for a broad array of speech?

On a personal level, each of us tends to enable or inhibit free speech through our everyday actions: how we engage with various individuals and communities, how we uphold (or fail to uphold) basic responsibilities to recognize and respect lesser-heard voices and opinions, how we acknowledge and adjust for the potential harms of speech, how we exercise care and conscientiousness with language, how we apologize for our own imperfect speech and forgive others for theirs. Operating individually according to these everyday principles can go a long way towards establishing constructive public discourse — despite our differences, despite us living in a very diverse and polarized and digitized society where speech can easily get weaponized. We can accomplish all of this on a personal basis, without dabbling too much in counterproductively policing each other’s speech, and while still promoting inclusivity.

I also absolutely believe we need to address systemic social disparities that shape all of these interpersonal and institutional tensions. PEN America for example has done a lot of work reaching out to universities, trying to help them uphold free speech and academic freedoms — all while embracing the imperative to transform themselves and become much more diverse, equal, and inclusive. This goes beyond just admitting students from varied backgrounds and hiring professors of color, extending to the ways that universities teach courses, support students and faculty, develop systems of reward, design and display campus iconography, and much more. We prescriptively argue for (and work with administrators and faculty on) fulfilling this dual responsibility. We want to see US universities remain intellectually vital places, in large part by transforming to meet the needs of a rapidly changing student population that includes many more people of color, many more first-generation college applicants, many more immigrants. Today’s universities must uphold the values both of unfettered intellectual freedom and of determined inclusivity. If they can succeed at fulfilling this dual responsibility, then they can empower a rising generation that sees how these principles come together to our collective benefit.

Alongside universities of course, Internet platforms, publishing houses, broadcast media, Hollywood, and all of our other cultural gatekeepers need to work vigorously to open themselves up, and to foster constructive conversations. Social-media companies, for example, now exercise an almost overwhelming influence on our discourse, and bear a great deal of responsibility for the quality of our public conversations. When they don’t embrace these responsibilities, they put our basic sense of social harmony and stability in peril.

We’ll need to address all of those broader social forces. But first could you further clarify why your own response to many such 21st-century concerns starts with searching for common ground on self-regulating open and accessible speech environments — rather than with increased reliance on government, institutional, and corporate powers imposing clear and stringent standards of speech?

Free speech stays vital by constraining the leeway of the powerful (whether government, corporations, or various cultural gatekeepers) to constrict the rest of us. And yes, this leeway differs in each case. Government possesses the power to check our speech most forcibly, through the most intimidating and draconian tactics. Only government can throw you in its jails for expressing views it dislikes. So we shouldn’t equate this power of government with that of other institutions. But we have seen historically that when you afford whichever authorities the power to regulate speech, they do so in very self-serving ways. They punish their critics. They suppress challenges to their rule. They exercise this dominion to reinforce their own advantage.

China’s authoritarian government today treats dissidents, critics of Xi Jinping, and independent thinkers as threats to the state. In Hong Kong, authors, booksellers, and media figures have been targeted and silenced — in some cases used as examples signaling to others the perils of expressing dissenting views. You don’t have to arrest or jail many in order to bring about a broad-based public recognition that speaking out on certain issues can end careers, menace family members, trigger untold harassment, and land you in prison. China’s populace now knows that taking up sensitive topics such as Taiwan, Tibet, Tiananmen Square, or the abuse of the Uighurs can put you and your loved ones in imminent danger. Most people simply avoid such topics. Young people grow up with major gaps in historic knowledge as a result. So the impulse that we should turn to authority does worry me, and certainly departs from First Amendment protections built up by our courts over the past century. We’ve been the global leader in terms of taking the most constrictive approach to the government’s authority to constrict our speech.

Here why should our free-speech debates dwell less on whether we consider a certain expression worthy of protection, and more on when the very real potential harms of speech justify allowing government and corporate powers (say Donald Trump and Mark Zuckerberg, for two conspicuous examples) to flex their censorship muscles?

The types of speech that come up in free-speech debates almost inevitably offend someone. No one contests anodyne speech. It is uncomfortable speech that creates the issue. We may have no natural inclination to defend particular expressions. We may find them objectionable, or simply disagree with them. But if you believe in free speech, that should compel you to uphold the rights of speakers in general, with less concern about specific content. If instead you demand bans and punishments for speech with which you disagree, and at the same time express outrage when someone seeks to curb speech you do support, that’s just hypocritical. That undercuts your own position. This doesn’t mean you have to treat all speech equally, or defend the content of expression that you abhor. You can rebut, refute, and even condemn speech while still defending the right to voice it.

So for example, after the Charlottesville attack a couple years ago (when Heather Heyer was murdered), the Springfield, Massachusetts Police Department had an officer who essentially posted on Facebook that protesters had kind of asked for it by standing in the street. It was a horrific comment. A broad range of people would have regarded it as deeply offensive. The Springfield Police Force fired this officer, which I don’t think caused much protest at the time. But then fast-forward several years, and just a few weeks ago, a different detective with this same department posted on Instagram photos of her niece at Black Lives Matter protests, with signs critical of police. The department fired this officer as well, citing the exact same social-media policy applied in the previous case.

Here again, government restrictions on speech, which may seem perfectly legitimate in one context, can seem, when applied to an alternative viewpoint, out of bounds. So we do need to think carefully about empowering authorities like police departments to exact punishment purely for speech. Of course for people who have committed racist conduct, or have a track record of treating others unfairly, they might (and probably should) face a different kind of judgment when their speech crosses lines. I don’t argue that no justification ever exists for punishing speakers. We often need to look at individual cases in context. But we also have to beware that punishments for speech, even for speech we abhor, can create precedents later used against speech we very much value.

Now to flesh out how a duty-of-care approach can help to establish general principles of reasonable reciprocity and empathic tolerance, could we start by outlining certain protocols for speakers? Could you give some examples of why, when, how speakers should recognize their place within a diverse society, presume a communications environment that can instantaneously strip speech of its context, calibrate the social or institutional power of their speech’s impact on others — and, at the same time, persistently push themselves to express difficult (sometimes inchoate, sometimes challenging) thoughts, as well as to defend others doing the same?

First, I recognize that this asks a lot of anyone [Laughter]. And I’d argue that this duty of care varies depending on one’s public profile and position of authority. When you have your own TV show like Megyn Kelly, speaking off the cuff about a sensitive topic like blackface is a big risk. Megyn Kelly, like all human beings, deserves to have a group of friends who know where she’s coming from, and help her to relax, and don’t attach much weight to every single utterance she makes, and encourage her to broach challenging ideas and complex responses to tense social concerns. But to speak glibly about blackface before a huge national audience, and then express affront that certain people seem upset by what you just said, suggests a serious lack of awareness about the actual diversity of your audience, and about how far your statements might travel without much background context. If you have a team of high-powered researchers and producers behind you, you should know that blackface is considered racist.

Similar issues still come up when the N-word gets used in an academic context, say when quoting authors like Mark Twain or Martin Luther King or James Baldwin. We’ve now seen time and again that, for a rising generation of students, to hear this word spoken aloud often registers as profoundly offensive. At first, a series of incidents just sort of blindsided professors. They thought it was perfectly apparent to everybody involved that they would never use this word as a slur. They couldn’t conceive of anyone taking offense. But by now, following at least half a dozen high-profile incidents, every professor has basically received advance notice. If you want to use this word, maybe you at least should have a discussion with your class ahead of time. Maybe you should give them a sense of what you aim to do with this word, and see how they respond to that. As a professor in 2020, you can’t just say (as some professors still do): “I’ve done it this way for years.”

The duty of care obligates us to educate ourselves about how contexts change, and social values change. If you stand before young people for your job, you need to try to stay on top of these changes. I don’t mean to describe any of this as easy. I’ve certainly made mistakes. Almost every speaker deviates on occasion from what most of us would consider a thoughtful and sensitive enough way of expressing something. We can’t expect anybody to get it right all the time. But if we exercise conscientiousness and reciprocal sensitivity, then hopefully we can cut down on the number of inadvertent offences, and create a bit of space so that when someone makes a genuine mistake, other people can recognize this and forgive it.

From the perspective of an offending speaker, what can constructive apology look like? And while “accepting blame for having done something wrong while in the same breath turning the tables on your accusers is hard to pull off,” how do we as a society stay real about the fact that an offended party is not always inevitably right — and that it might divert or exhaust any speaker to take up every single report of offense?

Yeah, and of course your life experience shapes how you hear everything everybody else says. Alongside race and gender, all of these other facets affect how speech lands for you. You can experience trauma in response to comments that would just roll off somebody else’s back. So we can’t apply any one single standard.

But specifically in terms of apology, the main thing people get wrong is to offer a pseudo-apology, with no genuine sense of contrition. Instead this amounts to a defensive projection. I mean, we’ve all heard apologies phrased as: “I’m sorry you got mad about my comment” [Laughter].

Of course instances do occur when the offence comes out of subjective impressions, or a misreading of a statement’s context or intent. In the book, for example, I describe a certain audience taking offense to the term “welsher,” as a supposed insult against the Welsh people. Here the offending author effectively demonstrated that this term’s etymological origins come from sources having nothing to do with the Welsh. But this author also persuasively conveyed never intending to impart offense, and recognition that the term nonetheless had done so, and respect for the feelings of those offended. So sometimes the appropriate response can offer something short of an apology, while nonetheless acknowledging that a collision of sorts has happened, and that you want to put things right.

Then as listeners (or readers) of speech, particularly within a heterogeneous society at times pushing everybody beyond their comfort zone, what can a principle of proportionality look like? How might this help an audience to balance, say: active alertness to and resistance of problematic speech, empathic generosity towards decontextualized speech, and measured forgiveness for errant speech?

Here again I’d first focus on context, which plays a huge role in how we make sense of any human expression. Very often in our digitized world, speech lands devoid of context. You see a tiny tweet or an article snippet or a meme or somebody quoted — but you don’t know the setting in which the person made this comment, though that could entirely shape its meaning.

Dare to Speak gives the example of a math teacher standing before his class, who suddenly saw his arm held at a certain angle, and made some muddled “Heil Hitler” reference. Taken out of context, his comment could come across as inexcusable anti-Semitism. The teacher was fired. But his students pushed back, convinced that any nefarious inference had been misplaced. It turned out this was just a very awkward, unplanned expression coming from the mouth of a teacher who had Holocaust survivors within his own family. This individual had zero record of anti-Semitism. This spontaneous gesture clearly had no bigoted intent, and eventually this teacher did get his job back through arbitration.

Here a principle of proportionality can help us resist the impulse, particularly online, particularly on a platform like Twitter, to let outrage blow out of all proportion. Often these eruptions might just involve many discrete individuals participating in the melee once or twice. But the end result can be tens of thousands of messages crashing the feed of a speaker who maybe inadvertently offended someone, or unknowingly misused a word, or clumsily phrased something — in a way that stopped short of overt bigotry. That kind of overwhelming response might shame this person, for good or bad, but also makes many bystanders more wary about tweeting the next time, and maybe becoming the next target of mass hostility.

To the degree that this prospect of blowback instills appropriate conscientiousness, it can have a positive impact. But when the cumulative reaction is wildly disproportionate, a chilling effect can definitely take hold. We’ve already reached a moment at which many people feel much more cautious. And again, we should welcome some of this heightened awareness of the changing world we now operate in, challenging the permissive character of certain long-familiar types of expression. But I do also see a big downside. Too many legitimate topics of debate (public-policy issues, international-affairs questions, even health and safety matters amid the pandemic) have basically moved off-limits. Speakers sense such a high risk of being misunderstood that it doesn’t seem worthwhile to get into it. Yet that doesn’t mean fundamental questions or tensions or problems for our society just disappear.

Again in terms of self-regulating our collective speech, could you further describe certain benefits of an occasional interpersonal or institutional call-out — alongside circumstances in which a well-placed, lower-stakes “call-in” might work even better?

This plays out pretty naturally for many of us from time to time. Someone sends a group email, and you sense the potential for readers to misinterpret certain statements. Instead of pressing “Reply all,” you write to that individual. You say: “Hey, you might want to clarify that you didn’t mean X.” You send the implicit message to this friend or colleague that you don’t want to shame or expose them, that you just want to help them mitigate the risk of misunderstandings and potential offense. Here also context plays a really important part. If the speaker can sense your own helpful intentions, then this speaker often can hear you out, and not get too defensive, and can take up your suggestion to rephrase or reframe or even retract something. Maybe the speaker pulls back an off-the-cuff tweet that really could have been phrased more thoughtfully.

Of course in other cases, a more public call-out might be warranted. A speaker has said something egregiously offensive. Many people have heard it. Some have felt harmed or even victimized by it. To distance yourself, and say that you reject this expression, can offer its own crucial sense of support and ally-ship to vulnerable audiences. So again I think of call-outs not as an unequivocal positive or negative. It always depends on the circumstance.

Here we also reach tricky questions of conflating speech and violence. So how do we factor in the harmful impact of hate speech as we seek to find the right balance of protecting vulnerable populations while maintaining the broader societal benefits of uncensored expression? And where in fact do conflations of speech and violence overextend themselves: reinforcing individuals’ sense of danger, justifying violent responses in return, and collapsing any civic space for various forms of nonviolent protest or disobedience?

First I do believe that we shouldn’t equate speech with physical violence. To my mind, this association comes out of the sense that our society doesn’t adequately recognize the harms that speech causes. I sympathize with this desire to underscore the very real damage done, whether by insulting or inciting speech, or even just by micro impacts of speech that somebody experiences as a pervasive part of everyday life. I would never doubt that ordinary language can come across as demeaning, and diminishing, and as designed to take away one’s sense of dignity.

Here again I can’t emphasize enough the importance of combining our support of speech protections with recognition of speech’s potential harms. We need to study these harms in our social sciences. We need to teach about them to a wide range of audiences. We need to raise our children into sensitive and empathic awareness of these harms. If we could do a better job of all that, then we’ll have a much more convincing case about the dangers of equating speech with violence.

You just summarized well some of these dangers. Overstating the harms of speech can quickly cause its own problems. If we enforce this idea of speech as violence, then what’s to stop you from punching in the nose the person who just insulted you (or might have insulted you)? That invitation to escalation can actually trigger violence, in a situation where violence doesn’t serve anybody’s interest, and where de-escalation would work much better.

Again, a broader international view points to the gravest danger, where entrenched authorities will use whatever prerogatives they have to clamp down on speech in very self-serving ways. The civil-rights movement provides its own clear historical example within the US. If the speech of demonstrators, if the symbolic acts of Freedom Riders, could be treated as something violent, then these could more legitimately be met with state-sponsored and vigilante violence. If you frame speech as violence, you essentially authorize the state to impose its own supposedly legitimate violence, as the only proportionate and sufficient response.

So now for even murkier modes of collective self-regulation, you trace some broader limits of an anti-appropriation agenda that, taken to its logical conclusion, could seem to: constrict prospects for writers from marginalized communities (if nobody else has the right to address your group’s experience, doesn’t that intensify the imperative on you to do so?), drastically reduce the range of creative speculation (how would any novelist, say, have the right to speak from some other person’s perspective?), and even outlaw certain forms of empathic reception (how dare you, as a reader, projectively identify with a given character?). Where might a reasonable duty-of-care approach make us robust but less rigid in how we self-regulate creative forms of self-expression?

I’d go back to the fundamental importance of dismantling barriers to access. One reason people justifiably get upset about such appropriation of stories and experiences comes out of the historical exclusion and marginalization of writers of color, particularly in terms of books that get significant support from publishers so that they can reach wide audiences. Those opportunities have been few and far between. We know this comes in part from publishing houses’ staffs being so white. So until these industry-shaping issues get addressed, until writers of color have equal access to channels of influence within the culture, and can get their stories out there in their own words, we will see this understandable questioning of why others seem to have received the opportunity to tell a certain story — rather than authors who actually come out of these communities.

Influential institutions need to address these issues before we reach the point where enough people will respect what I consider a fundamental principle: freedom of imagination, freedom to put yourself into different shoes, to envision different lives. Literature has always involved authors inhabiting worlds not their own, and inviting readers to do the same. You have to do this responsibly, thoughtfully. You have to do your research, consult with people, get a sense of how this story might land with different audiences. But we also need to give each other some basic room to explore. We actually need to figure out two important pieces of this puzzle. We need to remove barriers to access. And we need to make the most robust possible case for imaginative openness, both on the part of artists and of audiences.

Pivoting now to holding social-media platforms likewise to a more constructive balance of promoting expression, equality, and collective civic flourishing, what kinds of rethinking might we need around questions of algorithmic transparency, publisher-like responsibilities when it comes to curations of content, and even further accountability when it comes to advertising and commercial engagements?

I would come at this from two different angles. First, we need to be leery of giving corporations unfettered discretion to arbitrate and police speech — for a million reasons. They do a poor job. They bring their own biases. They think primarily about profits. Many people have gradually come to recognize these corporations’ ineffective approach to moderating content. So we can’t pretend that content moderation by such companies will ever offer any cure-all.

On the flip side, I also believe we shouldn’t absolve companies of responsibility for the externalities that result from their platforms. These quite serious and grave outcomes include catalyzing terrorist behavior, manipulating democratic elections, harassment of individuals, bullying, and a whole ecosystem of pernicious distortive content spreading exponentially through social media, with widely reverberating and negative societal effects. I do believe these companies have to bear some responsibility for all of that. So then how do you get the balance right between unfettered discretion and the undoubted harms that result when companies don’t moderate responsibly? No one really has yet devised the perfect system for content regulation and moderation. But a few attempts at least have gotten this process started.

You also mentioned transparency. We absolutely need better understanding by the public, by researchers, and by regulators of how algorithms work, which content they elevate, how this content spreads, the relationship between what happens on social media and real-world events, who’s behind various accounts, where we see signs of coordinated inauthentic behavior. Companies have gotten marginally more transparent under some significant public pressure. But researchers still have a terrible time trying to make sense of how these companies really operate. The platforms offer every excuse in the book to obfuscate — often under the banner of user privacy. Still I think we have potential here for real regulatory pressure. We can prioritize tearing back this shroud of secrecy encircling current content-moderation schemes, and we can do so without risking intrusive government regulation of speech.

Another piece of this might involve delineating different categories of digital speech. When it comes to paid advertising, for example, platform companies should face stricter legal requirements to verify who their customers really are — preventing, for example, foreign governments from masquerading as grass-roots US organizations. We need those higher standards of public transparency enforced, especially when it comes to knowing who produces, and buys space for, and places all of these messages before millions of us online. These companies have an obligation to protect us from what happened in 2016 (when, for just one example, many people saw promo ads for a supposed local Black Lives Matter concert, which actually came from a Russian bot).

Also for such companies’ own current self-regulatory operations, could you describe some best means of addressing users’ most pressing concerns — say in terms of inconsistent or opaque flagging, content-moderation, and appeals processes? What role, for example, might Public Content Defenders play here?

Look, we see so much pressure right now on these companies to aggressively moderate content. This has come to a head in the context of a recent advertiser boycott targeting Facebook. Inevitably, though, when tech companies move more aggressively into moderation, they also take down more content. That’s probably good when it comes to certain COVID-related disinformation: quackery and conspiracy theories undermining credible content from the WHO and the CDC and other health authorities. But this more aggressive moderation inevitably means that certain legitimate content also gets swept up and suppressed or deleted, with accounts sometimes canceled for no valid reason — and with, at present, almost no effective recourse for the individual on the receiving end. If your tweet gets improperly flagged or deleted, if your Facebook account gets deactivated (purportedly because of improper content you posted), it can feel just impossible to get a human being engaged in solving the problem. You often can’t even find out what infraction you supposedly committed, or how you could appeal. You just hit a roadblock.

But a Content Defender service, paid for by the platform, could build out a robust customer-protection arm geared toward people whose content might have been improperly suppressed. Users could contact these trained professionals, who then could report instances of problematic content moderation, and initiate a relatively streamlined review process — so that if, say, artificial intelligence simply failed to recognize satire or a semantic ambiguity, any suppressed content could be readily restored. Then in more complicated cases, an actual human advocate could push back against unjustified restrictions, could make the case that your speech should be publicly available, and could call for further remedies. This would shift the balance of decision-making power, so that as companies ramped up their moderation, they themselves would feel the need to watch out carefully to avoid false positives.

I also appreciated your take on how adherence to international human rights law guidelines can help both to make content regulation more fair, coherent, and transparent — and to catalyze our self-described civil-libertarian platform firms into standing up against intrusive government censorship around the world.

International human rights law offers a robust framework when it comes to protecting free expression, yet allows for a greater level of government intervention than does the US First Amendment. When it comes to platforms that operate globally, a strong logic exists for reliance on international law, to which virtually all countries already have formally bound themselves. Of course, whether individual nations live up to those obligations is a different story. Many do not.

And although international legal protections for speech formally constrain only governments, not private corporations, we can draw some analogies in terms of how digital-platform speech restrictions might be validly promulgated. In particular, we can apply the three-part test used to evaluate laws that impinge on free speech: is this law properly promulgated and not too vague, does it operate in the least restrictive means necessary to yield the desired result, and does it serve the public interest? If you think about content moderation (say in terms of Twitter flagging false statements by leaders) when applying those three rules, you’d want to ensure sufficiently clear and comprehensible guidelines, putting people on notice about what falls out of bounds (for example, through a policy statement offering samples of permissible and impermissible speech). You’d want to ensure that these restrictions don’t reach too far (for example, by barring merely speculative speech, or some form of personal puffery short of outright falsehood). And you’d want to articulate the legitimate public interest at stake (say preserving election integrity, or public health).

Adopting an international human rights law perspective also allows private firms to push back against government speech restrictions. Companies can, and sometimes do, cite international human rights law when refusing to follow government policies requiring them to turn over data, or to otherwise cooperate with regimes seeking to repress free expression. In Hong Kong right now, for example, US-based social-media platforms have, for the time being, said they won’t comply with the Chinese government’s data requests regarding users in the territory. Platforms have experience dealing with such requests from China, and know that these requests often target dissidents. With China imposing its new National Security Law, the fear is that Hong Kong’s online-platform users could place themselves at great risk of facing punishment for exercising their free-expression rights.

I can’t talk to you, in your current role at PEN, Suzanne, without emphasizing, amid all the shocking and demoralizing news of the day, the sudden severe restrictions placed on a vibrant Hong Kong society that deserve so much better. How else does what we see in Hong Kong right now dramatize the stakes of this book’s foundational call both for free speech and for constructive, pointedly anti-authoritarian self-governance?

The situation in Hong Kong is incredibly poignant, and something we at PEN America have been tracking since 2015 — when we issued a report entitled “Threatened Harbor,” about encroachments on press freedom beginning to intensify at that time. We then released a report on the case of missing Hong Kong booksellers, and have made several trips to release our findings and talk with journalists, authors, and other residents. Incredibly courageous Hong Kongers of all generations have led the recent protest movements. They now face seeing this free society and culture they’ve always known snuffed out beneath the heavy weight of Beijing’s repression. It’s a very difficult time there for authors, journalists, academics, activists, and really anyone who relies on free expression as a lifeblood. I’ve been asked to do a book event via Zoom for a Hong Kong audience, and I admire the event organizers’ and participants’ courage in still holding open public space for conversations about free expression. Their enduring commitments should inspire us all.