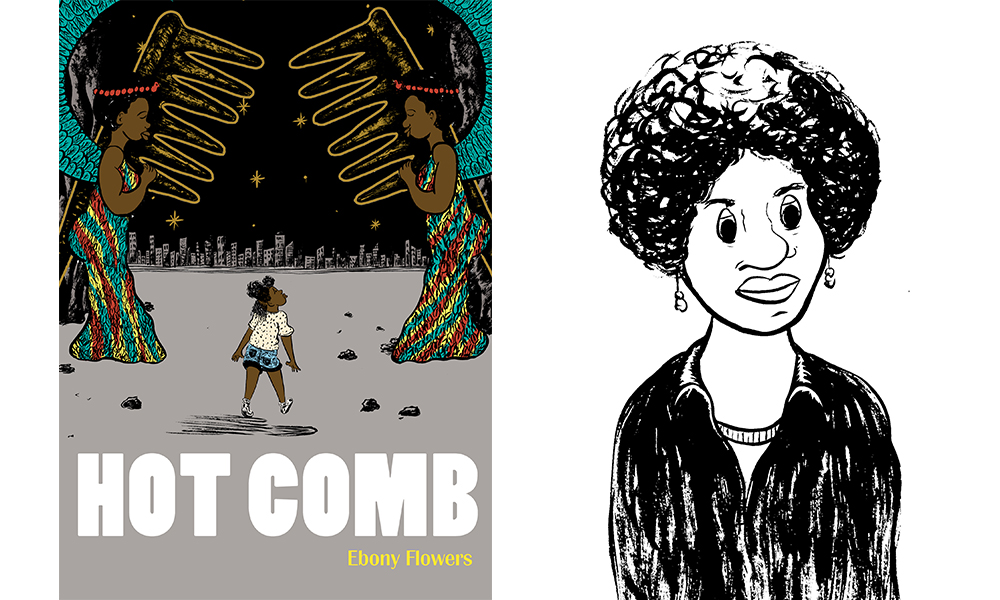

Ebony Flowers’s debut graphic novel Hot Comb is an exploration of the black feminine experience via hair. In a Proustian spirit, Flowers uses the hair-salon scent of ammonia and the caresses and yanks on the scalp to evocatively dip into her childhood memories of growing up — in Severn, Maryland and southeast Baltimore — and to re-conjure her realizations about class, gender, and the regulation of black bodies.

An ethnographer as well as an artist, Flowers renders her stories with a meticulous ear, eye, and textural sense, finding the details that richly invoke her lived experience. Hot Comb is poignant, funny, infuriating, and gorgeous. I talked with Flowers about Hot Comb and the ways she associates her hair with love, as well as racism, inequality, and injustice.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: While carrying out your PhD in Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, you wrote a large part of your dissertation as a comic. Can you talk about that process? Was your thesis committee on board with this approach or were you met with any resistance?

EBONY FLOWERS: My process for making comics for research is very different from fiction and creative nonfiction comics. I studied how groups of young children and graduate students drew together, used drawing to play and pretend together, and drew as a means of creating new knowledge. And yes, rather than write 300 pages of text, I drew most of my dissertation, featured my participants’ drawing throughout my dissertation, and analyzed all my ethnographic data by drawing. I authored my dissertation as a comic-zine hybrid.

At the time, there were few examples of comics-based approaches to research, generally, and of authoring a dissertation in particular. I had to figure out a lot of the process on my own. Doing ethnographic fieldwork was complex. A seemingly simple choice — “What am I studying and how?” — can have a profound impact on the kind of data generated and analyzed. Ethnographic research relies heavily upon data generated through the five senses and particularly sight perception. By making comics, I was able to more fully share my multisensory fieldwork experience with research participants and people outside of both my field and academia. I’ll never forget hearing from one of my committee members that her husband and child each read parts of my dissertation voluntarily, based upon their curiosity. That’s the power of comics in making research more accessible and engaging.

I was initially met with some resistance when I talked to my first advisor and committee about making comics as part of my research process and as my final dissertation. I eventually switched to another advisor who fully supported what I wanted to do and we worked together to form a new committee of mentors from various fields. My new advisor and committee were great! They asked critical and important questions that moved my research forward in interesting, insightful, and valuable ways. One thing they asked about was how making comics impacted my relationship to the research participants in my study. Their inquiry led me to include examples of how sharing comics with those in my study changed the way I understood validity in research. They also suggested what theories and methods I could draw upon as a complement to my use of comics.

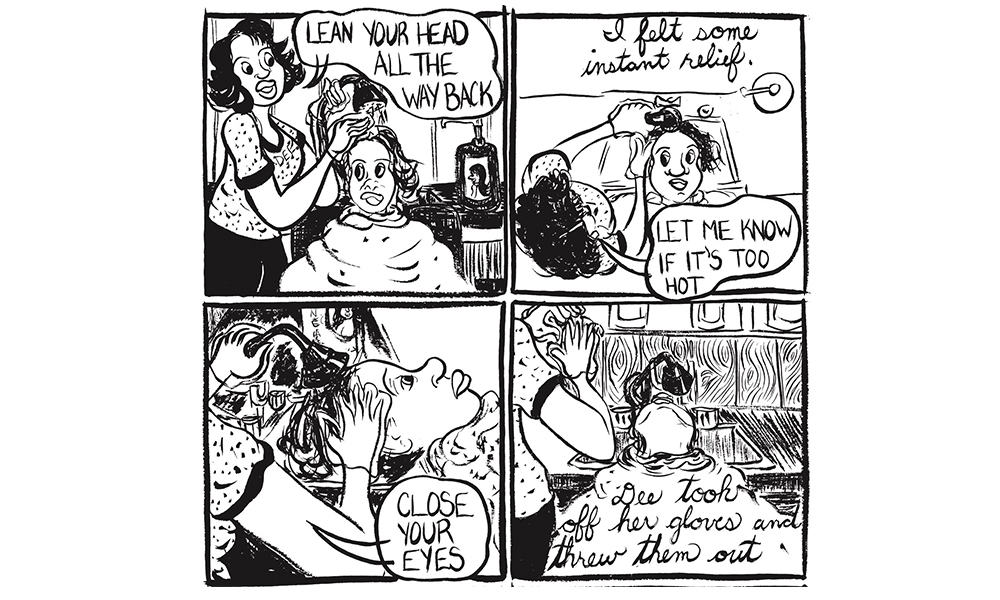

The experience of having your scalp touched triggers a dive into memory in many of your comics. Can say a bit about working the channel between sensory experience, memory, and storytelling?

This is probably the ethnographer in me. I’m curious about how my memories — and other people’s memories, too — are tied to the senses, particularly touch. Memories triggered by engagement with one or more of the five senses can conjure up transformative moments in a person’s life. Unexpected sounds, scents, tastes, sights, and tactile experiences can move people outside the present moment and into a more playful space where past, present, and future come together.

This is what happens in “Big Ma,” one of the stories in Hot Comb. The act of Cora touching her grandmother’s hair sends her back to her grandmother’s apartment. She is simultaneously at her grandmother’s apartment and at the funeral. Cora is experiencing her child and adult selves — and I drew those experiences together, as if they’re touching, because they are. The unexpected aspect of the senses and memory is key. A person, like Cora, is more likely to experience this playful space when they are caught off guard by a sound or scent or taste that ignites a memory. And that, then, becomes an interesting story.

My relationship to my hair is intertwined with sensory experience, memory and storytelling. I’d also add family intimacy and belonging. I take time showing black women getting their hair done because it’s an intimate interaction that often involves family, friendship, and a lot of conversation. Growing up, I loved getting my hair done by my mother. It was our special time together. She was the mother of three children and worked two jobs. I treasured sitting with her on Sunday afternoons while getting my hair braided. She’d ask me about school, my hopes, and dreams. I’d tell her stories about what happened at school and around the neighborhood. She’d tell me stories about her childhood. These were the first moments in which I witnessed the power of sensory experience, memory, and storytelling. And it was all connected to hair.

Do you know what the story is going to be when you first set out to write and illustrate a comic or do you find the path along the way?

I work both ways. Most days, whether or not I’m working on a specific story, I do timed spontaneous drawing and writing exercises entirely by hand. Sometimes, one of my creations from this daily practice will later become a fuller and more detailed story. “My Lil Sister Lena,” another story in Hot Comb, emerged from one of my daily drawing and writing exercises. Though the story is fiction, it was inspired by my memories of playing softball as well as my friend’s dissertation that examined the experiences of black women who play collegiate sports like soccer, swimming, and field hockey. During the process of drawing a more detailed story, I’ll make quick sketches of each page in my notebook. I drew “My Lil Sister Lena” in a process that mimicked free writing. Whenever I wasn’t sure of how the story would proceed, I drew individual scenes from multiple perspectives on index cards. I also worked out some of the main character’s life and mannerisms using my daily drawing and writing practices.

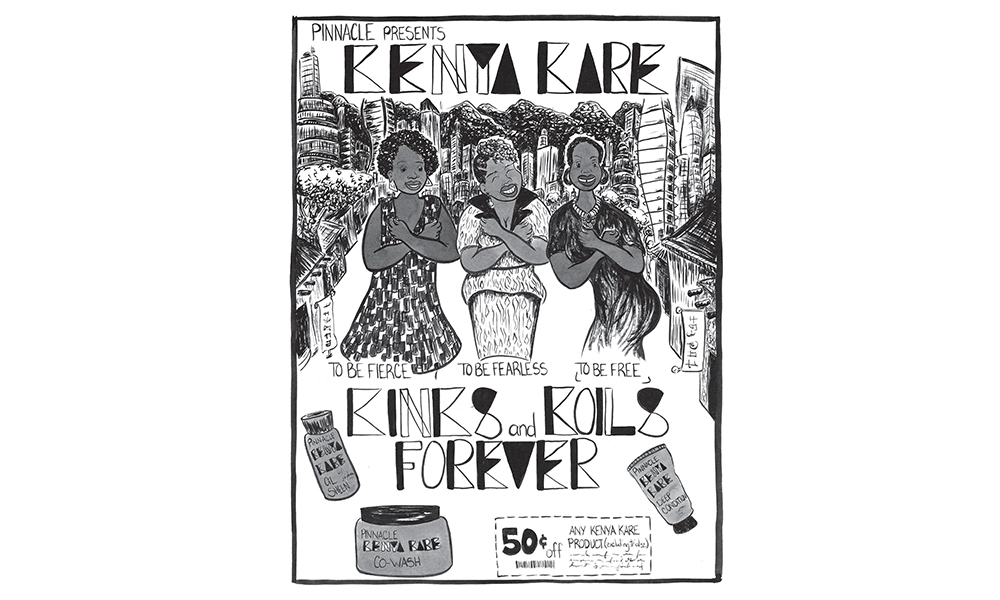

Your chapters begin with advertisements for hair relaxers, serums, conditioners, and wigs. To what extent were you inventing while creating these and to what extent were you purely reflecting the marketplace for hair products for black women?

The parody ads are from my fake hair care product line called Pinnacle. These fake ads were recently featured as an excerpt in The New Yorker in which I explained my personal history reading magazines like Ebony, Essence and Jet as a young girl while getting my hair done. Reading these magazines, decades ago, I never questioned what the many hair-product ads were really trying to sell to me.

I drew these parody advertisements to playfully critique dominant culture and mainstream messages about whose beauty matters, how corporate interests reify whiteness and white beauty standards, and how these harmful messages continue to proliferate in ads today. I also drew these ads to celebrate black imagination. A lot of the hair product ads found in vintage Ebony, Essence and Jet magazines playfully insert black people in scenarios, places, or American experiences that have been historically denied to us. That’s why you see not-so-subtle visual references to vintage black hair product ads, Black Panther, Game of Thrones, and Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy. Through playful criticism, I’m conjuring up a future in which black women can be viewed as inspirational while loving their hair.

Who were the primary influences on the creation of Hot Comb?

Hot Comb features — and is primarily influenced by — everyday people. My comics about black hair are everyday stories about black women like my mother, sister, aunts and friends. Creating Hot Comb, I returned to my training as an ethnographer when completing my doctorate. Ethnography is a way of studying people and their culture. I know how to study, draw, and tell stories about the everyday and about everyday people. I love to draw the lived experiences of people who seldom have the privilege of telling stories or of having their stories told in comics.

In this respect, Hot Comb will be a mirror for some people and a window for others. What do I mean by that? Stories that might appear somewhat foreign to some readers are the lived experiences of other readers. Of course, this dynamic certainly isn’t unique to my stories. That’s the case with any book or story authored by someone whose life experiences are underrepresented or misunderstood by a dominant culture. Nonetheless, Hot Comb is a comic so it’s a more accessible window through which others can perceive different life stories. I want all kinds of people to read and learn from Hot Comb. Ultimately, I wrote Hot Comb for black women — it was black women, their stories, and their experiences with hair that primary influenced these comics. But anyone can read my book.

When did you first start making comics? What were the models for doing it?

I drew my first comic in early 2012. I was deep in my graduate studies and looking for distraction. And it was the dead of winter in Wisconsin. That prior fall semester, someone named Lynda Barry had been announced as the next artist-in-residence at UW-Madison. I had no idea who she was. And I had no idea what her course “What It Is, Shifting the Manual Image” was about. But her work and her course sounded interesting, so I applied. And among the dozens and dozens of students who applied, a handful were selected. And so Lynda taught me how to make comics. And she also taught me how to be a more curious person.

I was looking for alternative means of representing ethnographic research, though at the time I couldn’t precisely put that into words – or into images. And no surprise here, her course was amazing and transformed my entire trajectory as a graduate student, as an ethnographer, as someone who could create images. We’ve been working together ever since. Lynda eventually became a professor at UW-Madison and started the Image Lab at the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery. I was her project assistant. For about five years we did a lot of work at the intersection of science, education, and art. Any model I have for making comics emerged from my work with Lynda and our Image Lab adventures.

What are your tools for making comics? Have they evolved or changed over time?

I make my fiction and creative non-fiction comics entirely by hand and I only use a computer to do final copyediting. I primarily use a graphite pencil (2H), Staedtler’s non-photo blue pencil, several round ink brushes (size 2, 4, and 6), and Yasutomo water-soluble sumi ink. I’ll try any kind of paper at least once but my go-to paper choices are newsprint, computer paper, 3×5 lined index cards, composition notebooks, bristol board (vellum surface), and hot press watercolor paper (140lbs weight). My choice in paper size depends on how large the final comic will be.

And yes, my tools have changed over the years. Sometimes, I use more expensive round brushes or Chinese lettering brushes. I’ve also invested in a decent lightbox.

I’m wondering if with comics like yours, with music like Solange’s “Don’t Touch My Hair,” with Phoebe Robinson’s essays from You Can’t Touch My Hair, if you sense any progress in the manner that white folks trespass upon black women’s bodies? Or do things strike you as just as horrifying as ever?

I see progress in the fact that black women are speaking out more about this kind of violation and its racist implications. We are also sharing our personal experiences in a variety of venues, through different media, and in all manner of stories that will resonate with black women of all ages. Part of our sharing often includes the revelation of pain, exclusion, discrimination, and frustration. I also see progress in broader civic life as New York City and California change policy so that black people’s hair is protected by anti-discrimination laws. Decriminalizing black hair is huge. The move acknowledges that having kinky hair has been treated like a crime. It also validates black people’s everyday struggles and sheds light on the fact that our hair can’t just be. Our hair is intertwined with the vestiges of racism, classism, inequality, and injustice.

Has your relationship toward your hair shifted over the course of writing Hot Comb? If so, how?

One of the great things that’s happened since publishing Hot Comb is that black women I don’t know, or who I don’t know well, have approached me at events and online to share stories about their hair. Their personal stories express a full spectrum of emotions — humor, pain, sorrow, love, and care. By welcoming and listening to their experiences, I’ve further opened up my relationship to my own hair. This relationship is no longer only about me; it now includes a broader shared experience that comes with being black and having kinky hair. Prior to Hot Comb, I only had this kind of relationship with close friends and family. Since publishing Hot Comb, it has been incredible expanding collective kinship and narrative through hair.

Where do you find your community as a comic artist? Is it geographically based (in Maryland, Wisconsin, Colorado, or elsewhere) or is it more remote?

I’ve been lucky. While at UW-Madison, I was part of a comics group that Lynda Barry organized. We got together once a week to write, draw, and make comics. This group had a profound impact on how I tell stories and do research with comics. Folks in this group taught me how to be brave in my storytelling. They’ve also given me technical advice about making and mass-producing comics. Over time, we began writing grants to bring in outside cartoonists to facilitate comics-making workshops for UW-Madison students and faculty. These workshops were for non-artists. We had people from wide-ranging academic fields such as chemistry, medicine, sociology, and education learn to make comics. Even though a lot of us have graduated, we still keep in touch, share our comics, and, sometimes, we’ll even get together to draw and write.

What are you working on next?

My next book will explore themes of environmental justice, redlining and housing segregation, and community perseverance. This book will be about the fabric of everyday life in a neighborhood wedged between the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and Baltimore’s industrial infrastructure. The Chesapeake Bay isolates the neighborhood from the rest of the city, causing the community’s structural and environmental issues to be readily ignored. The book is based upon the two southeast Baltimore neighborhoods of Fairfield and Soller’s Homes. My mother and father grew up in these neighborhoods. My maternal grandmother lived in Fairfield until the city forcibly relocated her – and everyone remaining in the neighborhood — to a housing project in the late 1980s. I was raised in and around both places.