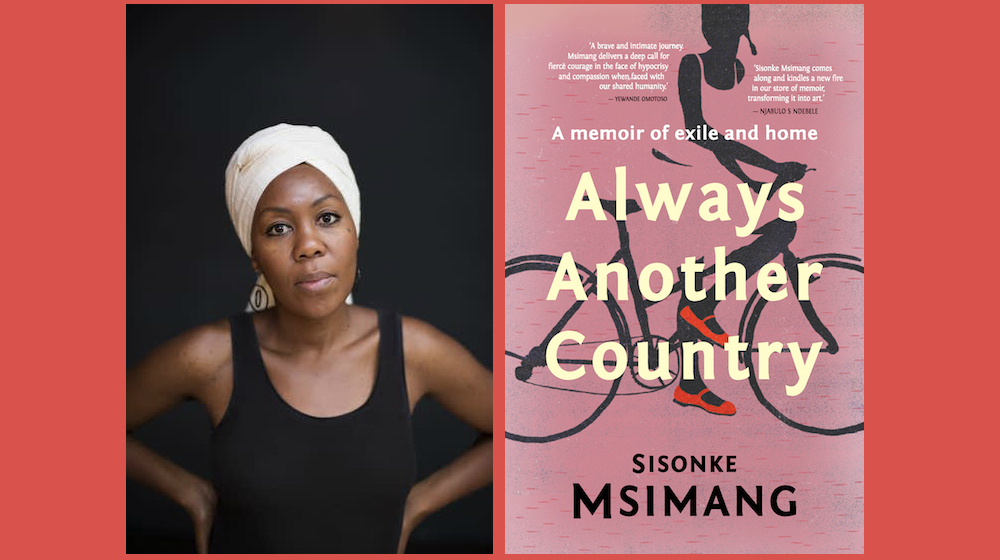

Sisonke Msimang is a South African writer whose work examines race, gender, and democracy. She regularly writes for a range of international publications including the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Guardian, Newsweek, and Al Jazeera. Sisonke and I caught up to speak about her recently released book Always Another Country, which is a memoir about exile, home, politics, belonging, and identity.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: Can you tell us about your early reading life? What stories were you drawn to as a child and what books left a lasting impact on you?

SISONKE MSIMANG: As a child I read everything in the house — both books and magazines. I loved National Geographic, I read Little Women and lots of books about horses. I was an indiscriminate reader when I was a kid and because I was rewarded with compliments whenever I had my nose in a book, I tried to read things I was sure not to understand simply because I knew it would impress everyone. Not a great strategy when you have no clue what any of it means!

You grew up as part of the South African diaspora living in many places on the African continent and North America. Can you speak about how this sense of home and this movement contributed to your desire to become a writer?

Because we moved around a lot, I was always looking for continuity and consistency. In some ways books provided that. We were an English-speaking household, and we lived in English-speaking countries in Africa and North America. So I could always check out library books or swap books with friends. So my first identity when it comes to books, was as a reader. Books were a sort of home for me. And so in some ways, the state of rootlessness that accompanied our many moves, combined with the relative safety of books made reading (and later writing) a familiar place for me. I only came to writing late in my life. I always wrote — especially in university — but I didn’t see it as a viable option, in terms of a career. As a middle class African woman whose parents had drummed into my head the idea that I had a responsibility to help rebuild South Africa after the end of apartheid, I really thought my role was in the professions — working towards making my country stronger. Writing just didn’t feature.

Tell us about Always Another Country. How did you come to write the book? What compelled you to speak about your life as part of broader historical changes in the world?

The good thing about getting older for me it that I have deepened my politics and begun to make connections that weren’t possible for me 20 years ago. So it was only in the last five years that I began to understand the way Nelson Mandela’s political choices had so profoundly framed the trajectory of my family. His radicalization and decision to form an armed wing of the African National Congress, triggered my father’s departure. His freedom signaled our ability to return to South Africa 30 years later. So my life is literally entwined with the recent history of South Africa. I am of course not alone in this regard and so it seemed like writing about my self would be a way of writing about politics but also of reflecting the experiences of many other South Africans whose stories have been overshadowed by the larger story of Mandela and his comrades.

One thing that many readers may notice is that there are layers and layers of stories here. It is a story about you, but it is also a portrait of a great many characters, from family to friends to lovers, and, all along the way it is a testament to the strength of women. Who are the other people in the book? Why them and what did you learn from writing about them?

Its really a story about my family — my mother plays a central role. But its also about people who were the casualties of apartheid — like Thandi Shezi whose testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission really haunted me. She was raped and brutalized. It’s also the story of these remarkable aunties I grew up with — Aunty Angela and Gogo Lindi — who were independent and rejected convention and who taught me a lot about fearlessness without having to articulate it as a politics. These days there’s a lot of talk about how brave people are. The women in my stories didn’t talk about being brave — they simply lived their lives in the most courageous fashion. Writing about them was helpful because I had always assumed my feminism was the result of intellectual decisions I made in high school and at university. Looking back, it would have been hard for me not be to be a feminist given their influences on me.

How does this fit with other questions of identity, in particular a question having a double-consciousness of place that has always been political, of how you have moved in real and literary terms?

It’s interesting, I tried very hard not to write this book in didactic terms. I didn’t want to write about identity (though I did in places) I wanted to weave a sense of how the people I grew up with were these eccentric, funny, fully human characters — which unfortunately, is still seen as political. The fact that they are contemporary complex Africans not living in villages and traveling the world and continuing to be African — well that is who they are. And yet writing about this is cast as a political act. Which makes me sad, but also, is part of the on-going battle black people face everywhere — both in real and literary terms. So there’s a double bind there — you are writing about yourself as you are and you are for yourself and for your people, but you are also conscious of constructing a new narrative about who you and your people are for an audience that has low expectations. The latter is not a huge concern in my mind, but they become a big deal because of how loudly they read, in other words, how much power they have.

In thinking about Always Another Country in our world and times, can you speak to what this act of reflection means now? The era of Apartheid and the early days of a free South Africa seem very different, from one another, but also from the world now. You talk about this in your other book The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela. What do you make of the current global situation?

Honestly, I am at a loss. I have been trying and failing for some time to wrap my head around the current global moment. The politics are nasty, the sense of being under siege is strong. I am desperately trying to be optimistic but I am struggling to find solid intellectual bases for that optimism. The act of reflection — of slowing down — is precisely what we need at this stage. Too much happens too quickly — without the time for reflection. And yet the forces propelling this speed are powerful. I have kids, and the pace of rage, and the speed of anger; the ways in which we are wreaking damage of the environment more quickly than we ever have even as we are more aware of the effects of our actions — these things literally keep me awake at night, fearful for them. Writing about this must be part of resisting them, but I will be honest, it feels incredibly tough right now.

Building from this last question is the question of how writing matters now and what kind of work it is called upon to do. You are a board member of PEN South Africa, and continue to be active there despite now living in Australia. Talk to us about PEN, free speech, and the responsibilities we have as citizens and writers?

I’m also a member of PEN Australia and for me the PEN movement is a crucial part of a larger strategy to ensure that the speed and pace and nastiness does not crowd out the spaces for reflection. Writers need freedom in order to think. It really is that simple. Where state and private actors try to curtail the freedom of writers and artists to express themselves, where they try to hold back our ability to think and to share our words and ideas, we see the collapse of democracy, we see the collapse of protections of the environment, we see corruption. So I see it as my role as a citizen of South Africa, and as a member of Australian society to advocate for space and freedom — even for views I don’t like. Not for hate of course, but certainly for the glorious right to argue.

Finally, what is the next long piece of writing you are working on, and, how does it respond to a future that we are making as we go along?

Oh the hardest question of all! I am interested in small town murders. I am also interested in how much the language of the culture today is drawn from trauma studies — the rise of the use of the word “triggered” fascinates me, given how often it is used in non-trauma settings. So somewhere between those two interests, I am hoping to write something that makes meaning of where we are — at least for myself.