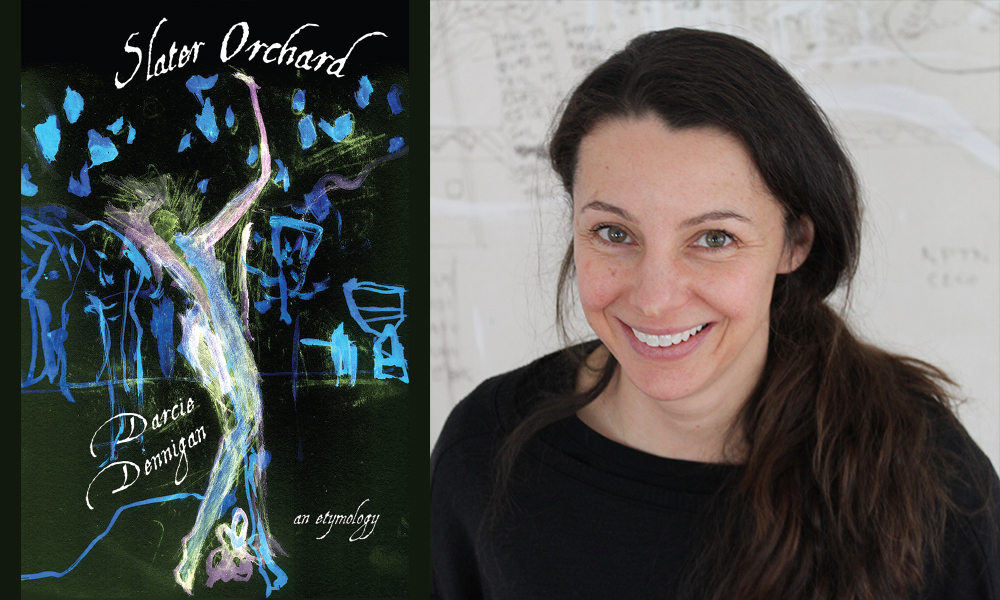

I first met Darcie Dennigan at a poetry reading at her home on Slater Avenue, a few miles from Slater Mill, the setting she borrows for the hallucinatory and obsessive world from her new novel. Dennigan is also a poet and playwright and Slater Orchard is about a cleaning woman struggling to start a pear orchard on a toxic waste site. “Slater Mill was the first mill, and the biggest,” Dennigan writes in Slater Orchard. “All the mills are quiet now and the river too. The mills killed it and its bend. The mills make nothing now but I am trying to make an orchard.”

Like David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Slater Orchard is lush and obsessive, twisted and lyric, a novel about a woman who’s conveying a nearly implausible yet unwavering world. The protagonist seems insane except that she’s so confident and convincing. “The way we say burial around her sounds like berry-all. Like a jubilee for raspberries,” the protagonist of Slater Orchard explains. “Though the way we say raspberry brings us back to death. Rasp berry.”

Dennigan’s prose is rich and gritty and it evokes the visceral instinct to survive even under nightmarish circumstances, to even start a pear orchard. I talked to Dennigan about her surreal and lyric new novel and her radical catalog of work.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: The site of the orchard in your book shares at least a name with the historic textile factory Slater Mill a few miles up the road from us in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Can you talk about what role the actual place Slater Mill had in creating the world of Slater Orchard?

DARCIE DENNIGAN: I live on Slater Avenue. It is a nice street. Often I think about my street being named for the mill a few miles away. Slater Mill is “the birthplace of the American industrial revolution,” a phrase that heralds a positive sense of firstness, progress, labor. It’s sometimes hard for me to shake, the positive connotations of those words. Even though Rhode Island’s towns and cities rest on brownfields and superfund sites and skeletons of exploited workers… And then — people are making things on those sites. Strange Attractor Theatre made a ghost piece about the women who worked at the Paragon Mill in Olneyville. On the old Colonial Knife site, What Cheer Flower Farm grows flowers that it donates to homeless shelters.

Back to my street — I can’t stress how pretty it is. Maybe it’s where the mill owner lived, several safe miles away from pollutants and misery. But prettiness is nearly always eerie. Slater Mill ran on the Blackstone River, which in the 1990s was the most polluted river in the country, according to the EPA. What can you do with a ruined world? I don’t really know. I was looking out my window and thinking about all these things. I pretended you could make an orchard.

With its abandoned mills turned into apartments, its sprawling derelict factories covering toxic water, this strikes me as a very Rhode Island book. When did you arrive in Providence, Rhode Island and can you tell me about what it’s been like learning to write about a world proximate to it?

I’m no stranger to Rhode Island. I grew up here. I used to be loathe to admit that, especially to the non-native writers and friends I’ve met here. I used to wish that my choices brought me to Brooklyn. I’ve always longed to be in the middle of all the literary action. Ha. (Or longed to be a part of the conversation, but without social media. All I can say is, come to Providence and find me. We can talk in the kitchen when my kids go to sleep.)

Since I was young, I worried that I was going to die here, another non-notable, small-life person. As an adult I have worried most of all that being a Rhode Islander meant an inescapably parochial mindset. Well that may be true. All I can do is read.

My three sisters live here, and my mom, and my stepdad, and legions of nieces, nephews, cousins, aunts, and uncles. I am surrounded by people I love, and by people I want to spend time caring for. So though I’m a native Rhode Islander, I did have to learn to write about, as you put it, “a world proximate to it,” because my Rhode Island is family and caregiving and cleaning and zillions of pizza dinners. Never mind a paying job. No one in my family would notice if I stopped looking at my window and thinking. If I stopped writing or publishing. They would notice if I lost my job or if I did not show up at the next birthday party. It’s a check on my public ambition. (How much of all this is due to my being female? Different interview.) There’s no check on my private ambition. Nothing stops me from writing. Without writing, I would be a zombie.

That said, family, even my pretty chill one, pushes me toward conformity, toward being a property owner, toward selfishness and away from an attachment to other kinds of communities. All these things are dangerous to my writing mind. Reading like crazy is the counterpoise.

But your question — I was 33 I moved back to Rhode Island, to Providence, which is so so far in mind, and to a Rhode Islander, in miles, from other places in the state where I grew up: mostly in Fiskeville, right next to the Arkwright Mills (named for Richard Arkwright, “father of the industrial revolution”), and in West Warwick, a ghost town of mills. My first poems were me trying to be the Bruce Springsteen of working class West Warwick. My parents divorced and we moved to Rumford, RI, a place named for its mill — the Rumford baking powder mill. I lived on the street named for the chemist who developed the powder — made from calcium acid phosphate — which I think he derived from bones and teeth. A street named after someone who made bread from bones.

At the back of the Magda Szabo book The Door, it says that Szabo died with a book in her hand, in the place where she was born. If my ashes were (illegally) scattered (may I be burned with my favorite books) over the gravesite of my grandmother in St. Mary’s Cemetery in West Warwick, with a view of the factories, okay.

You call Slater Mill an “etymology.” How does the study of words and language play a part in this book?

It’s not really a study in the scholarly, intellectual sense. Maybe study in the historical sense of push, knock, beat.

Sometimes I notice as I’m writing that I’m using words in such a familiar way — they are grey blobs, abstract. What do I really mean. What am I really talking about. What is the word carrying inside itself.

There are some novels, poems, radio programs that I can only just stand. Or cannot stand. They use words in such a way that the words have no body.

It’s okay, we all do this — hard to avoid. Also so dangerous. All words lead to living or to dying.

Slater Orchard is about poison. There are invisible poisons in the air and in the water.

And if I was looking for poison, it felt right to also dig into the words and see what they were/are. Make them three-dimensional again. But that was just a mode of working. I guess I kept “an etymology” as the subtitle because I wanted readers to know that I was working in the truest way I could.

There are certain ways the protagonist propels herself forward through this story but she also keeps burying dead babies and trying to make dirt in the dumpsters. How did you strike a balance between forward progression and circular obsession in this book? Were there rules for the story that you set while writing it? What did you think Slater Orchard was going to be when you first started writing it and how did that idea evolve as it was written?

I made no plans for this book. I had just finished Marilynne Robinson’s Mother Country about the Sellafield power plant, and I was just thinking about that book, and as I said, looked out my window to the street below.

I always write early, before my kids wake up and, man, the youngest one wakes up early. But I finished this book in one summer in the early mornings. It was kind of like a crush — that haze where you’re always ready to feel dreamy. I couldn’t wait to get up and sit with my notebook and see what happened. At night in bed, I let my mind get lost in what I had already written, and was careful to never let it go past the sentence I was at.

Though everything I was writing at the time felt spontaneously dreamt up, when I look down now I see that the collective unconscious or whatever you want to call it was at work… For instance, when the waves of blue foam in the book are killing the residents of the mill, I thought I was making that up. But the Yamuna River in India actually has more foam that I could have dreamt. And a couple of months ago, toxic foam swallowed a man near a canal in Puebla Mexico. Or there’s a poem in my book Madame X that’s railing against baby jails— a phrase I thought was absurd as I was writing it. Baby jails — I thought I was making a joke. Apparently my conscious mind is often too cowardly to admit the horrors of our realities.

What were the primary influences on Slater Orchard?

Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s The Orchard is one of the books of my life’s time. It is lush with death. (How can that be so? I will spend my life with the book open on my lap thinking about that question.) The narrator in Slater Orchard tries to make death luxuriantly fertile. Tries but can’t.

It was Brigit who told me to read Marie Redonnet, especially her trilogy Hotel Splendid, Forever Valley, Rose Mellie Rose. I am wild with love over those books. They make reading other novels feel like my brain is chewing egg carton cardboard. Those books don’t feel plotted. They enter the maelstrom and get sucked in and down and… the end. It’s someone else’s turn. Over and over the same pattern — Redonnet does this most explicitly in Understudies. I lay this book at her feet.

How do you find it being a writer and artist in Providence? Who are you collaborating with in Providence lately?

I would be a different writer if I lived in a different city.

When I first moved to Providence I ran a reading series called Cousins with William Walsh and Amish Trivedi. As Bill recently texted me, “Everything is a cousin to everything else” — a thought that Rhode Island literalizes.

I met my partner Carl Dimitri here. Among many other things, he did the cover of this book.

Right now I am working on an absurdist participatory lecture with Providence people Stine An, Mairéad Byrne, and Stacey Tran that we’re going to test out at &NOW.

Working with the fabulous horror writer and Rhode Island Humanities Council archivist Janaya Kizzie on an experimental theatre audio zine, Directed Dreaming. First issue is here.

I’m also collaborating hard, oh so hard, with the work of Hiromi Ito, especially Wild Grass on the Riverbank. Not Hiromi herself (unfortunately!), just her book.

For nearly a decade, my brain and spirit have been in continual communion with Providence writers Kate Colby and Kate Schapira.

But what I really want to talk about here is my current gig as resident playwright at The Wilbury Theatre Group. This fall the Wilbury’s artistic director Josh Short is staging an absurdist climate crisis play I’m working on called “Rescue!, or The Fish.” I wrote each part with a certain Wilbury actor in mind… And with this line in mind: “We are at the point where the world is as bad as possible, for beyond is the stage where evil becomes innocence.” That is Simone Weil, writing at the start of WWII. Well, we’re past that point now. My ignorance is my innocence is my evil.

I can’t say enough about getting to work with the Wilbury. When things coalesce and become clear for some brief moments, I know that writing itself is just a medium, and it will be destroyed — it’s the relationships, the collaborative energies, the individual movements we’re making alongside each other — that will get us closer to something.

Photo of Darcie Dennigan by Kate Colby.