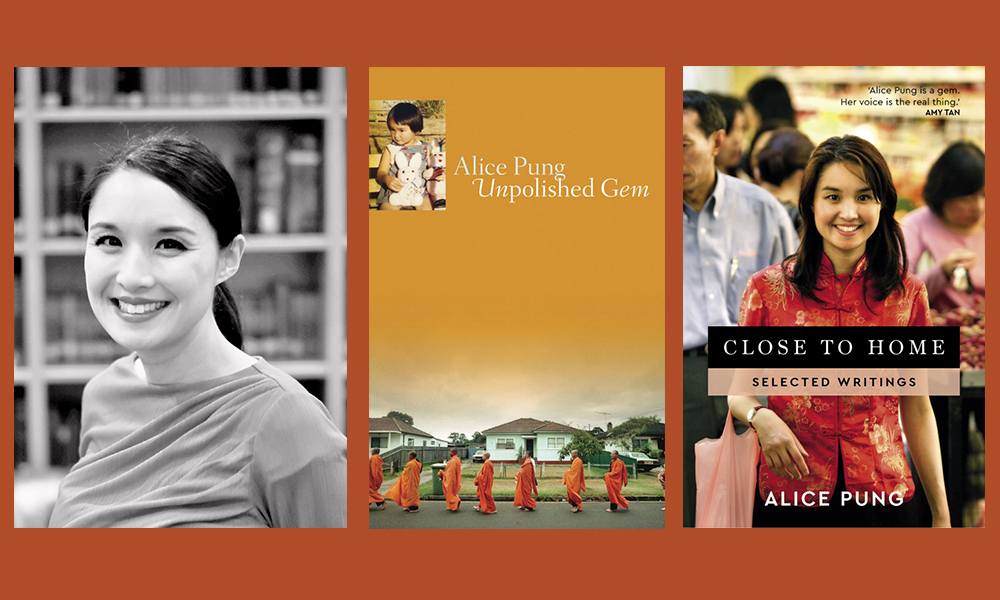

Alice Pung is an award-winning writer, editor, teacher, and lawyer based in Melbourne, Australia. She is the bestselling author of Unpolished Gem and Her Father’s Daughter and the editor of the anthologies Growing Up Asian in Australia and My First Lesson. Her first novel, Laurinda, won the Ethel Turner Prize at the 2016 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. Her latest book is Close to Home: Selected Writings.

I first encountered Pung’s writing last year when an opinion piece she had published in The Sydney Morning Herald hit my Facebook feed. It recounts the moment that she and her husband exited the local hardware store to find a folded piece of paper on the windscreen of their car. Unfolded, it revealed two children — one black, one white — encased in a red circle with a cross through it. Printed in large capital letters: STOP RACE MIXING.

Pung goes onto to recount a number of experiences from her lifetime, including a moment at a grocery store when she becomes invisible to the racist shop assistant because there is someone else at the counter who is more visibly different than her. Pung reflects that there is relief, guilt, and pity in this memory for her. As a biracial Australian, I understood her feelings immediately. I picked up a copy of Close to Home shortly after this and I was ecstatic when Alice agreed to let me pick her brains about her writing.

¤

JAY ANDERSON: Your memoirs, Unpolished Gem and Her Father’s Daughter, your novel, Laurinda, as well as your latest collection, Close to Home, have all been well received. You’ve mentioned that you realized you had a story or stories to tell at university, where a cup of coffee costs the same amount as an entire tin of Nescafé Instant, and where others perceived you in particular ways. Can you tell us more about this?

ALICE PUNG: As the first in my family to go to university, I realized for the first time in my life that entire groups of highly educated, middle-class people found me fascinating! I’d go to Socialist Alternative meetings and young socialists would love hearing about my mother being an outworker in the back shed. But when I tried to say that the work gave her a sense of dignity, and agency, they didn’t know what to make of me. This sort of narrative was not one with which they were familiar. They saw small brown people (women in particular) as victims to big bad companies, and there was an expression to accompany this: “the third world in the first world.” I’d never seen myself in such a light until I went to university. My universe exploded in all sorts of wonderful and disturbing ways.

This representation that you provide for “small brown people” through your storytelling struck a chord with me. Especially in Australia, where often the experiences of Asian-Australians aren’t shared in meaningful ways, our identities aren’t fully celebrated in our popular culture, and the toll of microaggressions on a week to week basis can make us feel unseen. Did you write with representation in mind, and has your writing practice helped you ground your own sense of identity?

When I wrote my first book, Unpolished Gem, the term “microaggression” was not one with which I was familiar. It was not in popular use yet here. I did not write with representation in mind, because the idea would have seemed ridiculous, as it does now — how can a singular voice represent a group of disparate people? It would be like Lena Dunham saying, without her characteristic irony, “I’m the voice of a generation!”

I wrote the book to figure things out, as a young adult, about my own life. Looking back on it, almost 15 years later, I realise why it had such an impact in Melbourne, the city in which I grew up — it was a working-class voice, but one that had somehow been published by a small literary publisher, and that gave people a glimpse into a refugee-migrant family that was more candid than the usual sorrow-to-success narrative. In fact, it is the reverse of this story.

If your writing allows you to figure things out, what is your practice and process like? Some of the pieces in Close to Home were about things that I never would have thought to write about — like the bells in “Spirit Chimes” and the wigs in “Hair Apparent.” How does a creative spark make its way to a short story, an essay, a novel?

I think I try and see the extraordinary in ordinary things in life, and this is an inadvertent gift from my parents. When they first came to Australia, straight from the Killing Fields of Cambodia and the war in Vietnam, they found everything here a true miracle — traffic lights, supermarkets, escalators. They took nothing for granted. To this day, my mother loves K-Mart and Woolworths. When you think about it, there is a whole world in each aisle of such places like Walmart and Target — every object must have passed through a hundred hands and quite a few continents to arrive at its final form, on the shelf. So I am most interested in the things — or people — we take for granted, and how we can see these things differently.

An inadvertent gift that has served you well in your writing. You’ve mentioned that your family has been supportive of your work. But what are some of the challenges of writing other people’s stories? Especially stories that they don’t want to tell. Your work made me think about my grandparents, who tell their happy migrant story. But I know that there is more to their story. How do you navigate the truth in telling your story and your family’s story?

This is a tricky question! To be honest, I just don’t do it anymore. I may have begun writing my first book when I was in my late teens and didn’t know any better, but now I understand the significance of publication and of having a voice, I am acutely aware I can’t use this voice to override those who are illiterate, or vulnerable, or who do not get the chance to have their say.

At some point, you have to weigh the consequences of hurting someone who loves you, with your sense of success and external approval. For me, the latter always loses out. That doesn’t mean though, that I stifle my writing. It means I ask others more for their perspective. I remember reading a great line that has often been attributed to the Torah: “We do not see things as they are, we see things as we are.” The purpose of writing from another perspective is to get as far away from your ego as possible.

When I edited Growing Up Asian in Australia, my aim was to include as many emerging Asian-Australian writers as possible in their own voices, and when we published My First Lesson, it was to publish an authentic teenage voice (and not adults masquerading as teenagers).

As you take care to consider perspectives, and writing these stories — your experiences and those of the people you love — how do you take care of yourself? Writing memoir, especially pieces like “The Killing Fields” or “Home Truths,” can be an exhaustive practice.

I had a lot of wonderful writer friends who supported me, and also friends who were not writers. They gave me perspective and let me take a breather from the intensity of diving deep into issues of trauma, personal and historical. Also, I take consolation in the fact that I never had to survive Pol Pot’s Cambodia, that I was born into this lucky country. It sounds like a cliché migrant-writer thing to say, but until I visited Cambodia, I had no idea how lucky I was or how my life might have detoured. So gratitude is also the antidote to despair.

This gratitude has propelled you to write in a number of forms, both creatively in your nonfiction and fiction, but also professionally as a lawyer. You’ve also visited high schools for talks, mentored university students, and edited other writers work. What benefits have there been to this diversity in your work life? How has it influenced your writing and what you’ve produced to date?

Because I write mostly from real life, and derive many of my ideas from life (even when I write fiction), I need to go out into the world and live life. I also need to feel like I am contributing to something larger than my own self-interest. Ever since I graduated from law school, I have held down a legal job. I work at a place called the Fair Work Commission, where I do research for the judges who make decisions relating to the minimum wages for Australian workers. It helps me from becoming too precious about the writing world. In other words, it keeps my writing pure, sort of like a hobby that I undertake when the need arises; and it stops me from becoming a wanker!

In this writing world, you moved from memoir into fiction. Memoir is difficult in that you draw from your own experiences, which are finite. Fiction is potentially boundless, but we draw from our own experiences nonetheless. Laurinda was set in Braybrook and Footscray for example, and the cliquey-ness of highschoolers is an almost universal experience. Was this transition quite natural? What are some of the challenges and joys of each form, and what have you noticed about the interplay between the two forms?

To transition between non-fiction and writing about my family, to fiction, was not too difficult because I write close to home anyway. It was also quite liberating because if your editor tells you to cut 5,000 words of your memoir, you think drats — I don’t have any more life experience with which to replace this! but with fiction, your ability to make up more stuff is boundless really. So the editing process is a lot more fun.

Where do you think your imagination will take you? What are you currently working on? Where is your writing taking you? Where do you hope it will take you?

At the moment I have discovered a wonderful Australian illustrator who depicts Asian children so realistically and beautifully and am working on a children’s book about overprotective parents (I am the mother of two boys), and I’m finishing up a book about a teenage girl who gets pregnant, set in 1987!

Photo of Alice Pung by Courtney Brown.