Sometimes you have to wait for the weight of a novel to hit you. Other times, you read a novel set 44 years in the future that’s about fake news, citizens having no trust in the media or government institutions, a refugee crisis, and an authoritarian police department, and those 44 years don’t feel so far away.

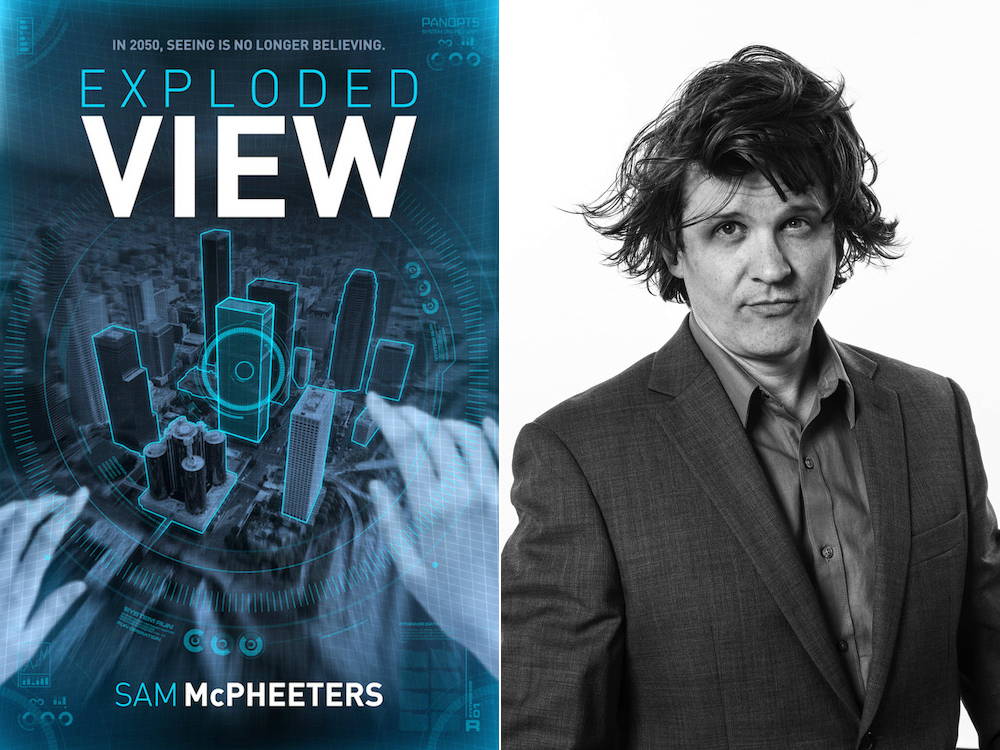

Set in the year 2050 in Los Angeles, Exploded View is author Sam McPheeters’ eerily clairvoyant novel about an LAPD cop’s attempt to solve the murder of a refugee. In McPheeters’ future Los Angeles, a claustrophobic war between India and China brings millions of Indian immigrants to the city. These refugees mostly live as squatters in skyscrapers downtown, which have been left vacant since most physical businesses no longer exist. Most commerce exists online, with only scavenging, hustling, food delivery, and police work done outside of the house, apartment, or hovel. McPheeters’ protagonist, detective Terri Pastuzka, leads us through this packed future Los Angeles, with the help of a gadget called PanOpts, a visor that allows her to view any video surveillance footage, or commandeer cameras, or footage shot by citizens. Regular citizens in 2050 Los Angeles have access to a similar gadget called an EyePhone, which allows it’s users to edit and remix any video, movie, TV, or news footage to their liking and post it online instantly, a little floating “R,” for “rea,l” at the bottom of the screen being the only indicator of if something the viewer is watching is indeed objectively “real.” I talked to Sam McPheeters about how it feels to see his ideas of the future come sooner than expected, how we’re in for some bad stuff, and how even though things look bad, this is not a dystopia.

SAM RIBAKOFF: I started reading Exploded View right after the election. In this near-future Los Angeles, people can remix and edit any sort of visual media, including the news, on the spot, through virtual reality glasses. How does it feel, now that we know so much of our election was influenced by fake news?

SAM MCPHEETERS: Yeah, it’s a little weird. I don’t know how to market this book now, because all the big social stuff [in the book] is happening right now, and not 20 years from now. I had a blog I set up in lieu of a book tour, and now I don’t know what to do with the blog because events are moving too quickly. There are so many stories pertinent to this book coming out right now that I just sort of threw my hands up. I also went on a news blackout a couple of days after the election, and even now I feel like I’m on a reduced input load. I wrote this book three years ago, which still was a year before Ferguson. There still was a little bit of that post-9/11 feeling of good will towards cops and firefighters, and that just seems so alien now. But yeah, the fake news stories are a lot more prescient, and a lot more depressing, than I thought they would be.

Was it a depressing process writing and researching and thinking about these dystopian ideas?

I have a high capacity for reading awful shit, up until the last couple of weeks. I think it took me a little bit longer to take a look back and have a good sense of perspective. I don’t think this book is supposed to be a dystopia, although that’s the way it’s being received. When I started in 2013, 2050 was as far away as 2013 was in the mid 1970s, when I was a kid. I remember that world well, and it’s not that different from now. The fashion is a little bit different, and the gizmos people have are different, but the basic facts of life aren’t much different. I’ve always liked science fiction that was underwhelming — like in Blade Runner when they showed old junkers. And I thought it was really silly when Harrison Ford talked about being in a bar in “the fourth sector” instead of being like, “Hey, I’m at a bar in Boyle Heights, come meet me.” But anyways, you could plop someone from 1975 in to today and tell them one set of facts and tell them they’re in a dystopia, and you can tell them another set of facts and tell them we’ve progressed a lot in some ways.

There’s always a tendency to over-simplify in science fiction, but really, some things get better and some things get worse. I’m pretty appalled with everything that’s happened this month politically, but I still have a good sense of perspective about it. There have been times in the past in America where things on the civil liberties front were pretty bleak; like the Sedition Act, you could go to jail for criticizing the government in a private conversation, and that lasted for three years, and had been in place once before that, during the Adams administration. Both times those laws were put in place, it was only for three years, I’m curious to know now what the time frame is going to be, because we’re due for some badness. There’s a tendency as Americans to not put up with huge infringements on civil liberties, for at least white America. Obviously there’s a different America if you’re not white, or if you’re not a male.

As a novelist, do you think you have the power or the duty to resist the shittiness of our time?

Hmmm, I don’t know the answer to that. I was in bands — [the punk bands Born Against, Men’s Recovery Project, and Wrangler Brutes] — for a long time before I wrote, and when I was in my 20s I really felt that there was an artistic obligation to tackle social issues, political issues. I don’t feel that now. I feel that if you’re a writer, or an artist, your obligation is to be good at your craft. Those two things aren’t in opposition to each other, it’s just that for me personally, I don’t feel an obligation to. I don’t ever think I could do anything completely apolitical, because that’s a large part of how I frame my worldview. I’ve toyed around with writing that was really political, try to show different sides to every issue. I’m really interested in the ways that people think.

You mentioned that you were in bands before — one of those was the punk band Born Against. Do you think punk failed politically?

No. When I was in bands in the early 90s, I very much thought in terms of pass/fail for political movements. I think it’s interesting that me and my friends who were in bands in the early 90s have a strong impression that the 60s were a failure, which is a very weird way of looking at an absurdly broad set of interlocking social movements. Some things could have failed, others succeeded. There was a strong divide between the punk and hardcore of the 1980s and the 1990s, and the band that I was in was right at the start of the 1990s bridged those two worlds really nicely. We also influenced a number of the punk bands of the 1990s is a way that I’m not completely comfortable with, which is viewing underground music first and foremost as a conduit for political action, and I don’t believe in that. I think first and foremost, if you’re in a band, your goal is artistic; it’s not emotional catharsis, or to inspire people to do things politically.

The bands that I really like now are the bands from the 1980s that don’t have that aesthetics, bands from Washington and Los Angeles. They weren’t concerned with social change, they were concerned with doing something artistically new, and that’s something that, as a writer, really inspires me. I would like to do something new. I’d like to have that as a guiding principle. If you want to be a political activist, then you should be a political activist, if you want to make good music, you should make good music. What I discovered was that being in a band, on a lot of levels, is the antithesis of engaging with the world. What you’re doing is going from town to town and putting on a presentation for people, like a play or a Powerpoint, and that’s nice, but it’s not the same thing as engaging with reality. You’re essentially striking a pose in front of reality, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

You said before that the world presented in Exploded View isn’t a dystopia, but where is the hope in that world?

I get that, but I wouldn’t say hope. Most of the people in this book live lives like the rest of us. You can say 2016 is a dystopia if you live in Syria; your life is going to be a lot shittier than someone living in the first world. Dystopia is also just this weird word for hopelessness, and I don’t think the people in this book are hopeless, they’re living lives like people right now are: they have jobs, they still worry about paying their bills, or their credit scores, or their crush. There’s a continuity with the emotional rhythms of day-to-day life that happen now.

What made you want to write a sci-fi book in the first place?

I was really interested in this concept called “soft content,” being able to manipulate photos and videos in real time with voice command. It has such huge repercussions for us as a species. What’s coming in the next two decades for us, technologically, has got to be on par with what happened when movable type was invented, or maybe we even have to go back farther. It’s going to be such a seismic shift when people can rework reality in such a way that no one will know whether moving images depict actual events in the real world. That’s just going to be massive for humans. I mean, we already see how massive it is because we can’t fully trust our news sources. The latest thing with this election is that everyone’s faith in the media has been shattered, my own trust in media and government institutions included. It seems to me that this is a really bitter foreshadowing of what’s to come. I mean, one of my main objectives in writing a science fiction book was that: this isn’t even science fiction, this could be marketed as contemporary fiction.

That’s interesting, because in your book a lot of people are totally disinterested in politics.

Yeah, and most of the young people think most of the news is fake. It’s not that they don’t trust the news, it’s that they suppose all news to be fake. This is how people have historically lived, I think. You go back 500 years, and if you heard news from a neighboring village, how would you know if it was true or not? People have always lived in their own version of echo chambers. The problem now is that these echo chambers are all personal and linked through social networking and exist in real time, and that’s just really dangerous and bizarre and interesting.

For this past month, with the election and everything, I was just like: “where are they going with this?” Whatever predictive powers I had, and I don’t consider myself a futurist, are gone. I couldn’t tell you what I think will happen by the end of December. I’ve talked to my parents and other people and asked them: “Is this what 1968 felt like?” All the answers were really complex, but one of the things that kept popping up was that this pace of change isn’t sustainable. This isn’t going to be what life is like in 2020. Things could get very ugly, but this level of unpredictability can’t keep going. This will probably will be a bad couple of years, but everybody has to live through those, our grandparents lived through World War II.

You live in L.A., but why do you think you set the story in L.A.? And why is L.A. such a good city to project the future onto?

I don’t know, and that was a huge disadvantage while writing this book, because so many people have written books in a near-future Los Angeles. I wrote about Los Angeles because I’m here. I did a lot of walking around, taking notes. Los Angeles is also a really interesting place: its history, the way it’s laid out. I’m an outsider here, even though I’ve lived here longer than anyplace else. I’m from the East Coast, but I find the place really fascinating in a way that no other city has made me feel. Probably Blade Runner set the tone for a lot of people, which is ironic because it was going to be set in New York City, and the main set they filmed it on was actually the “old New York” set.

The different neighborhoods in the book ring true as different neighborhoods in Los Angeles right now, even if they have different names. A lot of the times different neighborhoods feel like totally different cities in L.A.

Yeah! I wish I had been able to sit in with more of that. I just ran out of time, or couldn’t figure it out, or I just wanted to wrap it up or something, I wish there was more like that, just people exploring science fiction through urban change. Have you ever read the book Time Again by Jack Finney?

No.

Oh, it’s a great book. It’s about a guy in the future who time travels back to old New York. Finney does a lot of exploring about how neighborhoods change, from a background that’s not purely technical. Like, there isn’t a lot about the technicalities time travel; it’s more exploring the city. But thank you for thinking that my book did a good job of that.

One might question after reading this book if you’re a Luddite, or are scared of technology.

No! I would love to live without my iPhone, but I don’t see that happening. I used to write in notebooks all the time, but I can’t do it anymore, most of Exploded View was actually dictated into my phone. I’m really excited to see what happens with augmented reality in the next ten years.

So you’re not scared of the future?

Oh no, I’m terrified, but what are you going to do? We’re all going to die. You just gotta put your mind around it and keep on going. And that’s just part of living in history. Big events happen, they seem like dystopia if you project forward, but that’s the nature of life: we’re all going to live through some big shit.