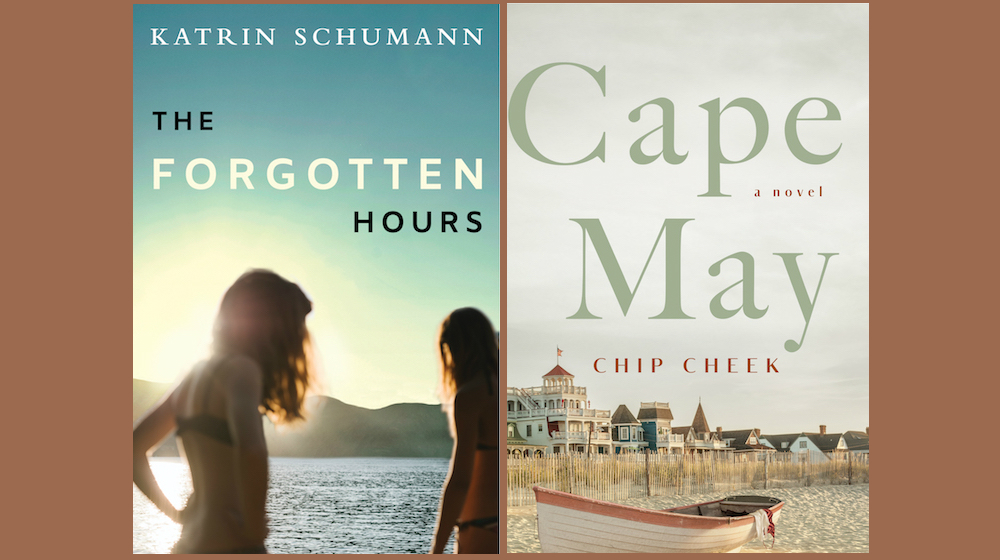

Katrin Schumann and Chip Cheek’s new novels may appear to be wildly dissimilar. Cheek’s Cape May (Celadon Books, forthcoming April 30, 2019), has been called “glamorous and nostalgic,” and centers on a naïve young couple from Georgia who, while on their honeymoon in Cape May, New Jersey, are corrupted by sophisticated urbanites. In contrast, Schumann’s The Forgotten Hours (Lake Union, 2019) is a ripped-from-the-headlines story about a family devastated by “he said/she said” accusations. Yet both books wrestle with similar themes that push their plots in surprising directions. Here, the authors discuss their preoccupations and goals.

¤

KATRIN SCHUMANN: Cape May captures this lovely sense of a past era, whereas my story is contemporary — yet we both seem to be interested in conveying the essence of lost moments of youth that are precious and fleeting. In The Forgotten Hours, my main character wrestles with her feelings about a past she remembers as pure and simple, when it clearly wasn’t. In Cape May, which is set in the 1950s, Henry and Effie are living in a time that modern readers often think of as idyllic, even innocent — and yet you reveal that this is overly simplistic. What got you interested in exploring this dynamic?

CHIP CHEEK: Let me say first of all that it’s such a joy having the opportunity to talk to you after reading your novel. It is absolutely riveting — and yes, there are several interesting parallels between our books. But to your question: I wasn’t consciously exploring that dynamic; I didn’t even know what time period my novel would be set in until after I’d finished the first draft. But I find it endlessly fascinating, the way our memories shape the past, and how we construct and dress up the past, including bygone eras. I mean, for whom was the 1950s idyllic and innocent, really? But those lost, precious, fleeting moments of youth you mention: those were definitely in my mind as I wrote. I was following a certain kind of thrill I associate with being young and blissfully ignorant: the thrill of endless possibility, of limitlessness — and also the danger in that thrill, the potential for abuse and self-destruction. I think that’s something The Forgotten Hours captures beautifully. I felt butterflies in my stomach when Katie and Jack rode off in the darkness to the empty house, where they could be alone: oh, I was a teenager again!

Thank you! I was trying to capture that sense of potential, of hope and trust, so I could show how it changes as we come to better understand the complexity of relationships and what people want and need from one another. In Cape May, Henry and Effie arrive on their honeymoon with a similar sense of hope and trust, mixed in with a good dose of fear because they know just how inexperienced they are, how small their world is. Can you tell me a bit about what attracted you to these two characters?

Effie’s a mix of all the tough, no-nonsense Southern women I grew up with — my mother, various aunts, my sister-in-law — so I love her and know her well. But when the novel takes place, she’s dangerously naive. Later in her life, she won’t be anyone’s fool, but that’s not yet the case in the novel, and that tension was interesting to me. Henry is essentially me — who I might have been if I’d come of age in the rural South in the 1950s: sensitive and loving but also self-absorbed, book smart but also ignorant, and a bit lacking in impulse control. I guess, now that I think about it, that’s no different from the me who came of age in the suburbs in the 1990s — except, thankfully, there was no expectation that I would get married right out of high school.

Where did your characters come from? What, more generally, attracted you to this material? The Forgotten Hours, which raises questions about consent, and about how or even whether we can forgive the bad behavior of men we might otherwise love, seems incredibly relevant to the current cultural moment — and yet the novel feels in no way contrived, and the characters seem in no way like assigned roles in a plot. They seem instead to be incredibly real and complicated — there are no heroes or villains here — and the whole novel feels urgently personal. Of course, you must have started working on this long before #MeToo, right?

Yes, some years ago, two close friends of mine were embroiled in legal proceedings around separate assault and consent charges — but each was on opposite ends of the spectrum. I lived the experience of feeling a deep loyalty that was badly shaken, and I learned how incredibly hard it is to admit to yourself that you might be wrong about someone. It’s so disorienting; you stop trusting your judgment, your memories, your instincts. Then, the Jerry Sandusky story broke (the football coach convicted of child rape) and I saw his wife on TV — grief-stricken, horrified, she was mumbling: “That’s not the man I know!”

In that moment I realized that this kind of story is truly universal, that at some time or another we all have to grow up and face our own weaknesses and decide how to move on. I also realized that all those who are accused of crimes (whether or not they’re guilty) have loved ones who suffer along with them. I think of them as peripheral victims: often generous, perfectly intelligent people, deeply influenced by their love and their sense of loyalty. I wanted to find a way to show how much we’re impacted by our limited perspectives, so I chose a very narrow lens through which to look: the daughter of the accused.

That’s such a fascinating perspective — the collateral damage. It’s a perspective that’s largely ignored when these kinds of stories break, so it’s great that your book brings attention to that.

Tell me about your choices regarding perspective, point of view. I love that we’re in Henry’s head, this passionate young man with a good heart who gets a crash course in his own fallibility and weakness. He’s so human, so flawed; it’s hard to pull that off in a protagonist.

Once I understood what my book was going to be about, I very briefly toyed with the idea of telling it in both Effie’s and Henry’s perspectives, but I quickly realized that wasn’t going to work — or rather, I wasn’t going to be able to pull it off authentically. Like it or not, I was writing a book about male desire (as if we needed another one of those, I worried at the time), and I wanted to write it as fully and honestly as I could. And when I finished, I felt like I’d created something fresh and new after all, something I hadn’t seen before, by fully embracing Henry’s weaknesses — his vulnerabilities, humiliations, blind spots, hypocrisy — in addition to all the good, hopeful, generous things about him.

I’d love to hear you talk a little about the complicated sympathies in your book. I think you made a fantastic choice in telling the story from Katie’s point of view, because it makes us sympathetic to her father right from the outset, even though we suspect from the beginning that her trust in his innocence is misplaced. And as the story goes along, he continues to be sympathetic: I love the scene, after he’s seen the hot-air balloons on his way home from prison, when Katie finds him weeping over how beautiful they were. He really seems like a good, loving guy — because he is, in many ways! I love how our feelings about Charlie, Katie’s mother, shift over the course of the book, too.

We all know on some level that people are complicated, but I think we still like to see good and bad as these mutually exclusive polarities, and what I find most perplexing about the world is that it absolutely does not operate like this. And so, given this reality, what role is loyalty supposed play? I was really interested in looking at that. Our evolving understanding of who Charlie is and what she did and didn’t do (and why) plays into this. In many ways, I think she is the most tragic character in the book. She decides to just walk away in order to protect herself, and she suffers dearly for that. For my story to work the way I wanted it to, I had to try to get readers to identify deeply with Katie (even if they’re sometimes frustrated with her), so they could understand how memories — shaped and sometimes distorted by the experiences of childhood — impact our perceptions profoundly. In other words, I wanted readers to see that contrary to what we believe, “truth” is not actually a finite concept. This meant that in terms of craft, perspective was the key that would unlock the door, so to speak.

Which brings me to this: If I had to describe your book in one word, it would be subversive. It’s surprising in such a quiet way and I wondered if this was something you were conscious of as a goal while you were writing?

Subversive — yes! I love that. I think I was half-conscious of it. While I was writing, I was more worried about it being the opposite. When friends would ask me what I was working on, I’d say I was writing a novel about more or less attractive white people having gender-normative sex — in other words, the least revolutionary novel ever written. But secretly, I knew I was doing something different: I was trying to write about things that most people know but don’t say out loud, the intimate unmentionables, from why you need a towel after sex, to the expansiveness of sexual desire. Dramatizing these things felt subversive — the most subversive thing of all being how and why Henry and Effie make their transgressions against each other. It’s not for lack of love or desire; in fact, they stray from each other when they love and desire each other more than ever. I guess this is the point you and I — and our books — keep circling: people are complicated.

I think something that haunts a lot of writers is that we wonder if our books will feel relevant to readers. We become obsessed with an idea and we hope that others will catch on and find those ideas worth contemplating, and that our efforts will be illuminating in some way. That our books and the ideas we explore will make readers’ lives richer. I certainly felt that way about Cape May.

I’m so glad! Generally speaking, I think when writers follow their obsessions, they’re inevitably going to strike material that’ll be deeply relevant to someone — and most likely to many, many readers, since people are more alike than they are different. I once had a writing instructor tell me that the way to get to the universal stuff is to dig down into the most specific, particular stuff, and I’ve found that to be true. You’ve certainly succeeded with that in The Forgotten Hours, which feels so relevant to the current age but also — in its atmosphere, in the specificity of the characterization — will likely be relevant for many ages to come.