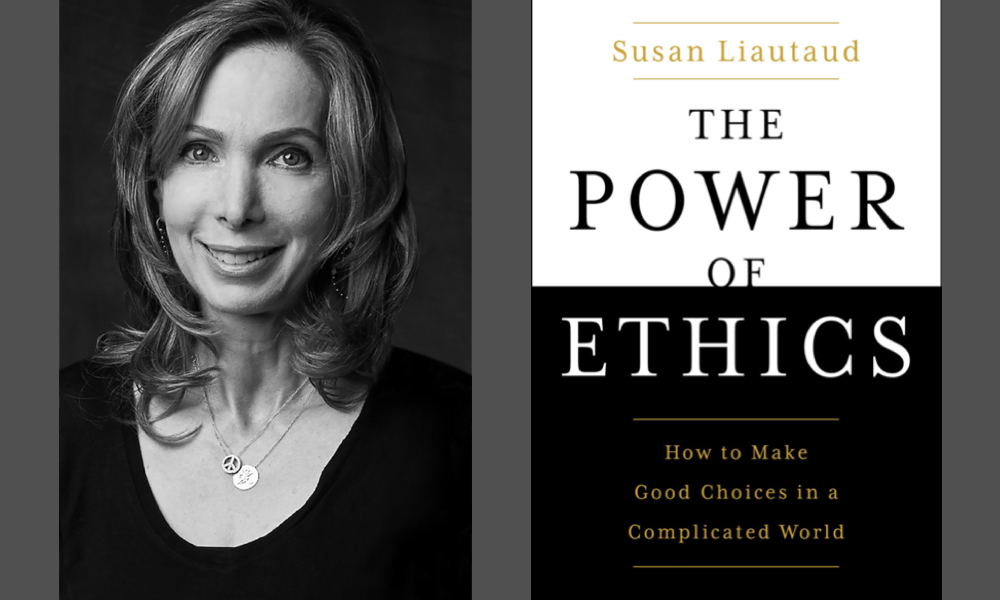

When should we think of our laws as “the lowest common denominator not the highest standard of behavior”? When might effective ethical deliberation look more like pragmatic problem-solving and less like moralizing judgment? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Susan Liautaud. This present conversation focuses on Liautaud’s book (co-written with Lisa Sweetingham) The Power of Ethics: How to Make Good Choices in a Complicated World. Liautaud is the founder and managing director of Susan Liautaud & Associates Limited, which advises clients ranging from global corporations to NGOs on complex ethics matters. She teaches ethics courses at Stanford University, serves as Chair of Council of the London School of Economics and Political Science, and is the founder of the nonprofit platform The Ethics Incubator. Liautaud also chairs and serves on a number of international nonprofit boards and ethics committees. She divides her time between Palo Alto and London.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you first sketch, from a “staunchly pro-innovation” ethicist’s perspective, what an edge of ethics might look like at present? Could you offer a few examples of where our laws don’t yet reach far enough to guide our actions, and where laws ultimately would prove insufficient anyway?

SUSAN LIAUTAUD: I see the edge of ethics as today’s reality. At the edge we have technologies (biotechnologies, for example), and we have very human challenges flowing from those technologies, challenges not governed by laws. We can’t just look to the law or to regulators for guidance. Instead, we need to rely on ethics. The bigger the gap between today’s reality and the state of regulation, the bigger the role ethics has to play. Even when the law functions well, it’s the lowest common denominator not the highest standard of behavior.

And today the law lags far behind in any number of areas. Take artificial intelligence. Today we need to ask ourselves, for example, whether police forces should use facial-recognition technology. But also, when I went to London’s Heathrow Airport last February, the last time I traveled voluntarily before COVID, I noticed an option for facial-recognition check-in. I had no idea what this meant. But I had this option. Out of habit, I opted to give my passport and boarding pass to a person. Though then in August, when I had to travel back home to Europe in the middle of COVID, everybody understandably seemed nervous standing there socially distanced and fully masked and the like, at San Francisco’s airport. And this time, I didn’t have the option for a person to check me in. As someone very ready to speak up, I looked around, at all of these exhausted COVID-stressed travelers preparing to board, and thought: Am I really going to be the one who points to the little courtesy sign and says, “I don’t want to do this. Can you please take me aside and manually check my passport?”

Here laws don’t yet guide our actions much. And with COVID, leadership also should have stepped up and better prepared us. In the United States of America, our first responders absolutely never should have needed to reuse masks. We shouldn’t have had massive PPE shortages. We’ve known for a long time that we needed to take pandemics as a serious possibility. So again the edge of ethics emerges where the law hasn’t caught up and may never catch up (as with artificial intelligence), and also where decision-making could have caught up but didn’t (as with pandemic preparation).

So every historical moment might have its own edge of ethics. But what today makes “a failure to integrate ethics into our decisions… the most dangerously underestimated global risk we face…. the existential threat at the source of so many others”?

First, ethics challenges today have become more virulently contagious than ever. Failed ethical decision-making has led, for example, to disinformation spreading around the world at lightning speed through social media. We see systems that we never thought would be or even should be connected (global financial systems, global health systems, etcetera) connected through artificial intelligence and other technologies, and no longer contained in local areas.

Second, the ethical consequences have become so much more complex, with far fewer people understanding the stakes. That also means fewer voices taking part in the decision-making. For centuries, medical expertise might have remained within the purview of medical specialists, but these experts could explain their medical recommendations in ways the rest of us could understand. If a doctor recommended getting your tonsils taken out, you could grasp the risks involved, and that you might have a sore throat, and might have some limitations on what you could eat for a few days. By and large, you could understand enough to give informed consent. But today, with the complexity of this reality on the edge, few people really understand the technological processes happening all around them. Again, think of how algorithms manipulate what information we see, or spread bias or the like. The distance has grown between what we can understand and what we need to know to make decisions, weakening pillars of ethics (like informed consent) that we relied on before.

Then third, we’ve really begun to blur humanity’s boundaries. We’ve moved fast towards Elon Musk’s Neuralink, and implanting chips in people, and growing organs in pigs for human transplant. The very question of what it means to be human needs a new ethical frame. The scope of our answers also needs rethinking. We have to take into consideration not just the immediate stakeholders. We’ve already seen, for example, human gene-editing go off the rails, such as when He Jiankui in China started editing embryos and influencing the human germline, with huge potential consequences for future generations.

Here how might you frame, in something like quantitative terms, the distinct responsibilities of wealthy, technologically dominant societies to think proactively (not just reactively) about their ethical decisions’ global impact? And how might you frame, in more qualitative terms, the importance of conceptualizing ethical reflection not as a projection of judgment, blame, criticism — so much as a positive, deliberative, problem-solving approach resilient enough to overcome our own inevitable missteps along the way?

Well, I consider it my mission in this book to democratize ethics. I hope to give readers some very accessible tools that can become habits for making effective ethical decisions about anything we face in our day-to-day lives — or even anything we see on the news. If we can develop these basic habits, then we don’t need to become experts in AI or in gene-editing or even in family dynamics to make good decisions. So I do want to focus on practical problem-solving. I encourage people to ask themselves: “What are the opportunities, and what are the risks? How can we maximize the opportunities, and minimize the risks?” And instead of making grand declarations about something being right or wrong, this ethical approach requires us to keep monitoring our decisions over time, as risks themselves keep changing, and as the opportunities evolve. So we do need to keep our ethics proactive. But we also need to develop an ongoing process of observing and adjusting.

Now, we in wealthier countries do face an added responsibility to consider all of the actual and potential stakeholders in our decisions. Today’s decision-making in developed countries has a huge and disproportionate impact on the rest of the world — from modeling a good mandatory-vaccines system, to making sure we consider the allocation of available COVID-vaccine doses to all nations (as leaders like Bill Gates have advocated). Important ethical decision-making also happens at the level of our individual voting. When we vote for president of the US or prime minister in the UK or president of France, these votes have an impact far beyond our own national borders. Here again, many stakeholders’ lives might be directly or indirectly shaped by our decisions.

Then on a global scale, most of today’s critical ethics challenges have no borders: as with the risk of Internet-based terrorism or conflict, the spread of disinformation, the spread of this pandemic. With COVID-19, many commentators have made the point that nobody’s safe until everybody’s safe. That same logic applies to many of our biggest ethical challenges, and stretches beyond today’s stakeholders to include future generations. We of course need to ask, for example, what kind of climate situation we wish to leave for our children and grandchildren. We need to ask something similar for all of today’s big ethics challenges.

To introduce here your “banished binaries” concept, where might you see at present clear examples of individuals or organizations needing to move beyond conceiving of ethical deliberations as “Should I or shouldn’t I?” imperatives, towards the more nuanced calculus of “When and under what circumstances should I or shouldn’t I?”

To start, I do still consider certain ethics binaries critical. After two Boeing 737 MAX 8 planes crashed in a matter of months, Boeing’s CEO faced a clear ethical-binary decision. Boeing still couldn’t explain the deadly crashes. Further human life was at stake. So Boeing only had one possible ethical solution: to ground the planes until it understood what had happened and how to ensure this wouldn’t happen again — and certainly not to lobby President Trump to keep these planes flying. We also see ethical binaries of right or wrong when it comes to racism, sexual misconduct, putting others at risk in the COVID context by disregarding scientific guidance about masks and social distancing. We do have an ethical responsibility to identify these binaries.

But for many of today’s circumstances on the edge, when we look for a clear yes or no, right or wrong, a couple things happen. We leave many opportunities unseized, and many risks unmitigated. Again with gene-editing, for example, we have fantastic new potential to cure horrible diseases, and to perhaps prevent the onset of disease in children. On the other hand, we don’t want to encourage a world of edited embryos and designer babies — and with little sense of the potential genetic consequences.

Or think of all the good that comes from social media connecting people, and giving people access to business and research and educational opportunities. We certainly don’t want to ban social media. But we should face up to the responsibility of developing social media while mitigating the risks of lost data-privacy, of mental-health issues, addiction, dysfunctional political polarization.

Particularly when it comes to balancing dynamic economic growth and societal/individual well-being, could you sketch, from your own wide-ranging professional engagements, differences in European and US approaches to pursuing benefits of innovation while taking precautionary measures to avoid preventable harms? Does one ethical model stand out as decisively better than the other here? Do you see possibilities to combine positive aspects of both approaches as we think through if/when to put the brakes on emerging technologies and innovations?

So, as a general matter, I don’t lean toward one or other of these models. But you’re asking an important question, Andy, because it points to how different cultures will have different ethical perspectives: in terms of which decisions they prioritize, and which information they most value, and whom they consider (and how they treat) the different stakeholders. To give one concrete example, several years ago I interviewed someone very senior in G7 discussions of data-privacy. And she said something along the lines of: “Europeans, and in particular the French, would no more sell their data than sell their organs.” By contrast, in the US we’ve been much more willing to give up our data — or we maybe haven’t fully understood what we’ve given up to get things like free Internet search and social media.

But now I think we’ll see an interesting regulatory process (regulatory arbitrage) play out internationally, with a good example being the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. This GDPR approach reaches much farther than anything tried in the US. But all of a sudden, for purely practical reasons, certain digital companies have told Canada, for instance: “Please just adopt the GDPR system. We’ll all have an easier time following just one system, rather than Canada setting up its own separate, slightly less draconian system.”

Though here I also appreciate your basic question of: how can we take the best from all of these different points of view, on these very complicated issues? I don’t have a straightforward solution to offer, but I’m working hard on this. Right now, we have a woefully inadequate global-governance or global-ethics infrastructure when it comes to these challenges. We need to think through what a real global-ethics infrastructure or institution or process can look like. It will necessitate a much wider range of voices than we hear today when it comes to how to manage data-privacy, how to manage bias, facial-recognition technology, gene-editing and the like. We’ll have to take ideas from everywhere. And we’ll have to welcome diverse views from people who do not bring, and shouldn’t be required to bring, technical expertise.

Now from a slightly different angle, for the acceleration of scattered power, and for scattered power’s indiscriminate potential to amplify good or harm, could we place, say, the manifold benefits of 3D printing alongside the unregulated dissemination of 3D-printed firearms? And how else do today’s tech products raise foundational scattered-power questions of: “Where is this power being generated? Who has it? How much do they have? How will they use it?”

Power is scattered more than ever. And no legal system assures that power will remain tethered to ethical decision-making (today or at any time), unless we make it so. By “we” here I mean each of us as individuals, and also corporations, NGOs, of course governments.

For 3D printing I can give a couple quite different examples. One of the most inspiring videos I’ve ever seen comes from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (where I’ve served as a volunteer advisory-board member for many years). They have a video you can find online where medical professionals in the field print prosthetic limbs in an incredibly short amount of time, for just a fraction of what prosthetics cost before. They can do skin-matching. They can even custom-design these prosthetic limbs to the particular goals of the people who need them. Someone might need to do strenuous farm work. Someone might often need to hold a baby. Someone might need to use their fingers in particular ways. The possibilities are extraordinary — as they are with 3D-printed shelters.

3D-printed firearms, however, present unprecedented dangers. The complexity isn’t that great, relatively speaking. The cost comes down every day. Before long, almost anybody could have the capacity to print a gun from their living room. We already have (especially in the US) a terrible gun-safety problem. And irrespective of one’s politics, I don’t know anyone who thinks that Sandy Hook-type tragedies represent how we want to be living in America.

With 3D-printed guns, the accessibility, the lack of constraints in terms of cost and complexity, the ability to evade metal detection, should terrify us all. So again the law has not caught up to the technology, and the technology itself makes prevention almost impossible. As with many forms of scattered power, the harms can be untraceable. As with many terrorist attacks or cyber crimes, even when the consequences have become clear, finding the perpetrators can be virtually impossible. Scattered power here doesn’t only increase the power of individuals and corporations. It actively disempowers the law.

Yeah, how can we most effectively ensure that scattered power doesn’t lead to a paradoxical monopolization of ethics — with one powerful corporation, one problematic state actor, one monomaniacal individual making crucial decisions impacting us all?

Right, at the same time that we see a scattering of power, we have this amassing of unprecedented power in certain corporate behemoths, in the technology giants, especially the so-called FAANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google). We face a two-fold problem here — recognizing the positives they also bring. Allowing firms to control or monopolize certain aspects of technology produces all kinds of significant consequences for business, for the economy, for inequality. But alongside the need for thoughtful targeted antitrust oversight and the like, and questions of who controls this technology, we also cannot let these corporate behemoths control our ethics, and make crucial decisions for our whole society. Especially when these firms themselves profit so much off of scattered power, they have a big responsibility to think through what kind of power they’ve made available to whom, and what obligations they have to help support our democratic decision-making, particularly on ethics matters.

That takes us to ethical contagion. Manifestations of ethical contagion make clear that our perceptions, ideas, and behaviors get caught up in complex, multidirectional chains of influence — even as the ramifications of our choices keep spreading and mutating into ever more disparate contexts and applications. Such contagion shows us, perhaps most of all, the limitations to prioritizing one’s “good” or “bad” intentions when assessing the ethical merits of our actions. So how might moralizing analyses fail to grasp, for example, certain “drivers of a national (and ultimately international) tragedy” like America’s 21st-century opioids crisis?

For one quick example of how ethics are contagious: we’ll see in the news certain repeated patterns play out over and over again. First one bank will manipulate LIBOR. Then the next thing you know, five other banks start doing it. That kind of contagious misconduct can spread fast.

But we also see mutation. One type of misconduct will transform into another. For one simple example: somebody will do something wrong, and then will lie to cover it up. So now we have multiple drivers (maybe greed, but also shame or fear of getting caught) at play. Though with many of these repeated patterns of wrongdoing, our society fixates on eradicating the unwanted behavior, without sufficiently addressing or eliminating the drivers of that behavior. Those drivers fall into two basic categories. The first, which I call classic drivers, include: greed, abuse of power, skewed incentives, racism, jealousy even. But we also have techier drivers on the edge, like: social media, artificial intelligence, gene-editing.

When we look at the opioids crisis, we do see in Perdue and some other corporations all the classic drivers of unethical behavior. We see greed, skewed incentives. We also see other drivers I haven’t yet mentioned, such as lack of transparency, weak compliance oversight, a sense of impunity, regulators not doing their job. At that point, the problems come not just from one greed-fueled company, but also from a whole supporting cast of characters.

Now we have certain doctors, maybe driven by greed and skewed incentives, transforming their practices into pill-mills (with opioids dispensed outside of the recommended guidelines), and we have other doctors over-prescribing just due to a good-faith lack of understanding about these drugs (or having been misled by the companies). Now the regulators get further implicated. Soon even well-meaning medical and dental professionals, truly trying to do the right thing, and following best practices, start contributing to this epidemic — by following increasingly misguided prescription recommendations. Now we have teenagers with no previous drug use recovering from routine knee surgery getting addicted, and eventually chasing heroin or stealing in order to pay for their fentanyl. We also start seeing global sourcing of some of these cheap substitutes, from places like China.

So until we eradicate all of these drivers, and until we get the incentives properly aligned, and restore functional regulatory oversight, we can’t just rid ourselves of this opioids epidemic. But much of our news coverage still focuses on the behavior of opioids users, or maybe particular problematic CEOs — while never really addressing the drivers of this behavior, and how far and wide they spur further misconduct.

Your “Contagion” chapter also sketches the corrosive impact of Lyndon Johnson-style politics on American democracy. But of course it’s hard to read about these dangers of compromised truth, these obsessions with retaining power at all costs, these exploitations of weak compliance and regulation, without thinking of Donald Trump. What do you see as the most worrisome contagions/mutations stemming from Trump’s behavior, even just since the 2020 election, that we now need to address proactively — before they fester any further?

I’ll start from the nonpartisan point that, without doubt, the single most contagious driver of unethical behavior is compromised truth. And technology drivers such as social media turbocharge this compromised truth by spreading its distortions. AI algorithms then reinforce what individuals want to hear, making it impossible for us to talk to each other.

That all adds up to polarization, further racism, political dysfunction. We can’t resolve any serious ethical challenge with compromised truth. Instead we get accusations about the election’s integrity. We get endless unsubstantiated questioning of the scientific evidence with respect to COVID-19. We cherry-pick certain convenient truths instead of addressing real problems. But there is no such thing as alternatively factual ethics. We see this globally with (and shouldn’t take our own political cues from) authoritarians using lies and distortions and concealments to control the narrative.

So if “When truth becomes an option, the whole ethics edifice collapses,” what would you consider some healthy ways for our democratic culture now to renegotiate questions such as: “Who gets to decide our truth? And what is our ethical obligation to society with respect to truth?” And how to cultivate proper viewpoint diversity in a national moment of such fervent, self-perpetuating self-delusion among so many of us?

I’ll give a series of partial suggestions, which will by no means amount to a comprehensive analysis of this mission-critical question. Social-media companies have a huge responsibility to reconsider how algorithms distribute false information. Twitter, for instance, has now pledged to take down false information about vaccines. But social-media companies also have a much broader responsibility to rethink what kinds of information get posted, and how. Obviously this requires a careful public debate, treading on questions of free speech and the like. Though specifically in terms of flat-out false information posing a danger to certain individuals or to society (through reinforced information silos and partisan silos), we need significant change.

Similarly, the mainstream media have a big role to play in defending space for public debate. Universities have a huge role to play. With free speech under threat on campuses around the world, these academic institutions have to stand up and defend open debate. That doesn’t mean encouraging disrespect. That certainly doesn’t mean tolerating speech that incites violence, or urges endangering human life. But it does mean taking on a public role as defenders of free speech.

Finally, we need to rethink the role of expertise. Experts have their own obligations (and I say this respectfully) to communicate in clear and simple and relevant terms. Experts face a real challenge addressing so much complexity in today’s world. But in order to rebuild trust in expertise, which has faltered in particular since 2016, we need to communicate much more effectively to the public — which includes sometimes saying: “We don’t yet have a good answer on that question.” So, for example, early COVID communications had some to-ing and fro-ing about masks. Here we could have had a clearer statement along the lines of: “This is what we don’t yet know…” Even that acknowledgment of our lack of understanding helps to clarify the public debate. And we can’t just allow our society’s technological expertise (and ethical decision-making power) to get increasingly sequestered in the brains of a decreasing number of experts, further distanced from the public.

Now for a few speculative examples of ethical challenges amid blurring boundaries, you describe our need at present to proactively define parameters of acceptable behavior in, say, a near-future society with widespread distribution of humanoid robots. Could you expand upon the implications of formulating questions here such as: “Who (or what) gets to do what to whom (or what); and who (or what) owes what to whom (or what)?”

Those questions appear in this book’s discussion of robot rights. My own opinion for now is that we have so far to go in defending human rights around the world, that I personally have little time to worry about robots’ rights. But your point gets to these bigger questions of: what are we creating? What kind of power are humans giving to robots? What kinds of consultation with the public do we need (with humans stakeholders already directly affected by robots: as they flip your burger, or greet you as a bot receptionist, or scan your face for the local police force) before corporations unleash this technology?

Right now, little of this technology faces the kind of process we have for getting a COVID vaccine approved. Little of this gets filtered through some sort of FDA or CDC or WHO or European authority’s approval. Creators of this technology can more or less decide on their own when to unleash it on society. For a couple positive examples of corporations putting on the breaks, Microsoft has said that the company will not sell facial-recognition technology to police forces until we have national human-rights protections regarding its use. Amazon, too, has declared a one-year moratorium on police use of their facial-recognition product, while hoping for regulatory oversight.

From my own perspective, no matter what the decision (how we treat a robot dog, or how we apply AI in policing or in sentencing guidelines, or whether we build robots with emotions), human beings and humanity must remain front and center at all times. And I’m no behavioral psychologist, but think of all the psychological and other social-science expertise we’ll need. What might children think if they see an adult swearing at a humanoid robot nanny or kicking a robot dog? Do they process the thought: Well, inanimate objects with a form of machine intelligence get treated as the machines that they are (like a hair dryer)? Like humans? Or differently from both? And what does that behavior say about how we think of ourselves as humans?

The ethics implications of our interactions with machines start with determining when we let machines make decisions (including how we embed human oversight along the way), how effectively we monitor and change course when machines “behave” badly, and how (decision by decision) we reclarify and insist on the boundaries between human and machine. “We” includes all stakeholders: experts, corporate providers of this technology, regulators, the media, academic researchers, and each of us.

Again, as an ethicist strongly supportive of societally beneficial innovations, I believe that if robot teachers or bot therapists offer the best means for reaching millions of people around the world, then we should embrace these technologies — which also involves doing everything we can to make sure they are safe, effective, free from unacceptable downsides. So you won’t hear me say: “Ban the robots.” But you will hear me stress over and over the need to keep our thinking about humans front and center.

So your book offers this concerted yet complex critique of treating machines like humans. Where have ethical deliberations taken you when it comes to treating animals like instrumentalizable objects of corporate profit?

That’s a complicated topic. I certainly think we need to address cruelty to animals in the familiar forms of corporate research, for example. Again, I’d stress applying “when and under what circumstances” types of questions. Research on animals to make a new lipstick strikes me as quite different from animal-based research that will save human lives. We also have, at least in the medical field, very clear guidelines about how animals must be treated in research. So again I don’t want to impose a binary, but I do want to emphasize the ethical need always to look for more humane alternatives and compassionate treatment of animals.

Food production also stands out.

Absolutely. If you look at arguments for moral veganism, many focus on how these animals get treated.

Returning then to future-oriented blurred-boundary ethics, you complicate classic control problems related to AI (“How do we stay in charge of these machines?”) by asking: which of us get to decide on the plan? Which of our diverse human perspectives get coded into algorithmic operations? When and how do we stitch “pause” or “off” switches into our technological rollouts, so that decisions of unprecedented ethical magnitude don’t get made in a governance/regulatory vacuum? Which AI control questions of these sorts seem the most under-asked today?

Well we definitely need a bigger emphasis on diversity — in all kinds of ways. We need the types of demographic diversity that we tend to talk about when recruiting for organizations. We also need diversity of thought, cultural diversity, of course global diversity. All of these technologies we’ve discussed have the capacity, and often the explicit mission, of reaching across borders. We can help people halfway around the world. We have so many interesting projects in the works right now. But we do need to make sure that we factor in all kinds of diversity when thinking about AI-powered decision-making. Again, we can’t think of ethics as a spectator sport, with most of us having no responsibility. And we also can’t think of ethics as a luxury item to which only the elite (the tech experts, the corporate controllers of this technology) have access.

What then more broadly can high-quality “ethics on the fly” look like? Where is it possible, and not possible? And how does it differ from just “holding your nose and leaping”?

Instead of holding your nose and leaping, ethics on the fly means being efficient in a couple basic ways. In certain types of situations, for example, you already have most of the necessary information. Let’s say you’ve been thinking for a while now about taking the car keys away from an elderly parent. I don’t want to generalize too much, but we all know that, past a certain age, this becomes a relevant concern. So then you can focus on questions like: does this person’s vision still suffice? Do they still have the reflexes necessary to handle a car safely? Ethics on the fly can work here as you assess the shifting circumstances.

Ethics on the fly also works well for questions we consider less important. We face these kinds of ethical decisions all day long. We don’t have time to belabor every question. When I want to watch Netflix, for entertainment, I start from knowing I won’t need to surrender my DNA to Netflix. And they tell me they won’t sell my data. So, honestly, I just don’t bother too much when I have to click on a consent form and agree to something. Ethics on the fly prioritizes picking one or two core principles that can drive your ethics for a particular question. That doesn’t mean disregarding all other ethical principles. But it does mean concentrating your efforts.

Ethics on the fly doesn’t work as well with, for example, thinking about gene-editing to combat a particular health issue. Instead you’d need to take the time to really understand what scientists know. What can this intervention predictably fix? What risks would it bring? What information do we not yet have? Where has scientific understanding not yet caught up to technological possibility? Another example is voting: we should take the time to consider the qualifications and character of candidates, and the consequences of their taking on this office.

Finally then, for long-term, forward-looking ethical resilience, how can we complement this robustly agile and preventative approach, by also cultivating a practical emphasis on recovery? How might we best address harmful ethical lapses that do occur, by applying a carefully calibrated commitment to mutual dignity — so that all stakeholders can pursue recovery? And how does such high-minded recovery depart from any blanket or unearned sense of forgiveness?

In order to recover ethically, three things must happen. First, truth needs to be told. You can’t have recovery without truth, any more than you can expect ethical behavior without truth. Anyone unwilling to tell the full truth about what’s happened doesn’t have the necessary foundation for recovery. Second, those involved need to take responsibility. Assigning responsibility doesn’t mean playing a blame game. Often, all parties have to say: “Okay, my part in this was X. Maybe other players also had a part, but I’m responsible for X.” In some cases, of course, one person does deserve primary responsibility. In other cases, we see more of a group effort. In Harvey Weinstein’s contagion situation, for example, both apply: he was the master perpetrator, but he also collected a cast of characters (literally) supporting his misconduct. Then third, for proper recovery, you need a plan to move forward to assure that this misconduct doesn’t happen again.

I don’t mean to make it sound easy to get these three requirements in place. But if those three things can happen, then we can rebuild and rebuild stronger. And to the extent that people already proactively try their best to integrate ethics into decisions, aware of their decisions’ impact on others, aware of the need to assess opportunity and risk (the “when and under what circumstances” approach, as opposed to the more binary approach), you already have a better foundation for recovery.

Now, on forgiveness, many wise people describe forgiveness as a matter for the forgiver — with less concern about what the offending party does, or whether they commit to improving. Forgiveness does offer an important way for the forgiver to find peace. But I think we need to distinguish carefully between forgiveness and ethical resilience. To the extent that we lack truth, accountability, responsibility, and a plan to move forward, we’ll likely face the kinds of contagion and endless repetitions and mutation discussed earlier. Whether someone forgives or not, the misconduct (and further mutations of the misconduct) will likely continue. So forgiveness has its place, particularly in one’s personal process. But to resolve real ethics problems, we need a more concrete plan for resilience and recovery.