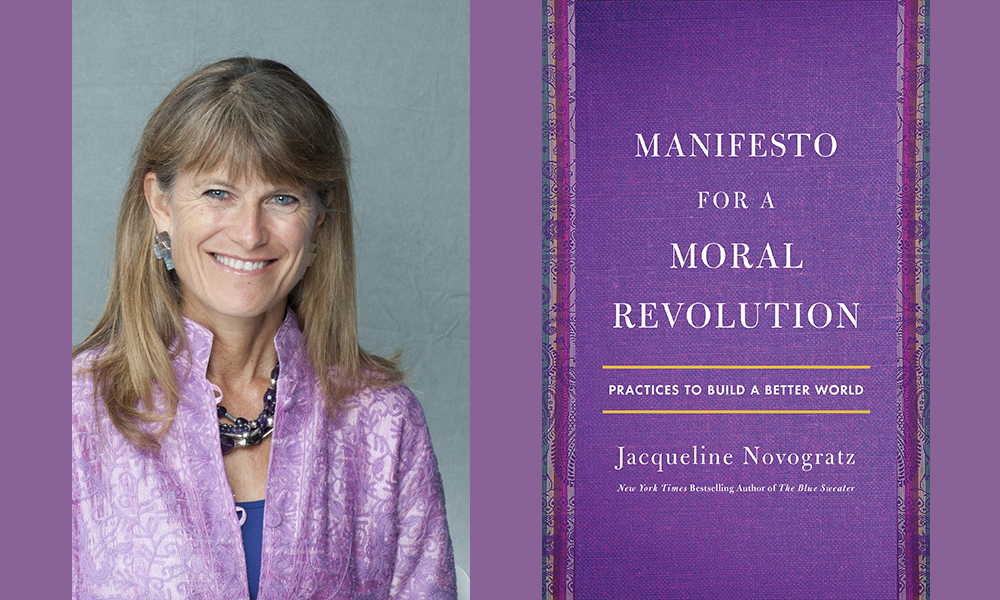

What does it look like “to use investment as a means, not an end”? What kinds of patient investment does it take to create a market where none existed, serving the needs of some of the world’s poorest communities? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Jacqueline Novogratz. This present conversation focuses on Novogratz’s book Manifesto for a Moral Revolution: Practices to Build a Better World. Novogratz is the founder and CEO of Acumen. As an innovator in impact investing, Acumen has helped to bring critical services like healthcare, education, and clean energy to hundreds of millions of low-income people. Novogratz is also the author of The Blue Sweater. She has been named one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers by Foreign Policy, one of the 25 Smartest People of the Decade by The Daily Beast, and one of the world’s 100 Greatest Living Business Minds by Forbes, which also honored her with the Forbes 400 Lifetime Achievement Award for Social Entrepreneurship.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you start from the informed-optimistic perspective that we have “infinitely more connection, tools, skills, and resources to help tackle the world’s injustices” today than we had when you began your work? For readers more attuned to globalization’s destructive impacts over the past few decades, what baseline case can you offer regarding the drastic reductions in extreme poverty (at least pre-COVID) that we all should appreciate?

JACQUELINE NOVOGRATZ: In the 1980s, most frontier economies struggled with staggering levels of underdevelopment. In 1986, 40 percent of the world lived in extreme poverty. Rwanda had an average income of USD $112 per year.

Markets began opening with the Cold War’s end, especially in China and India. That opening brought about incredible innovation and job creation. Today, less than 10 percent of the world lives in extreme poverty, a massive achievement. Yet the rise of unbridled capitalism and technologies also has left us more unequal, divided, and divisive than ever in my lifetime. Still, I am hopeful, but not with an easy hope — more of a hard-edged hope. I know change is possible. Change is also difficult. But nothing important is easy.

I started my career in the early 80s on Wall Street. I could see the power of using markets to enable innovation and efficiencies, at least for the wealthy. But at that point in history, the poor were fully excluded from the financial system. The poor basically had to borrow from money lenders charging extortionary prices. Seeing this sent me on an intellectual journey through the eyes of writers like Paulo Freire and Frantz Fanon, who helped me begin to look at the world through the poor’s perspective. Experiencing the vitality of street vendors in the favelas of Rio, and other cities where I worked as a banker, convinced me to leave banking and focus instead on bringing opportunities of the marketplace to people who had been left out. Or exploited.

Much of my life has been spent looking for solutions to poverty, seeing investment as a means, not as an end. I’ve mostly learned to reject easy ideologies and trite assumptions when it comes to solving problems of poverty. In 1985, before co-founding Rwanda’s first microfinance bank, I traveled to China. I rode on old trains, in the workers’ section, which had 90-degree wooden benches. My fellow passengers crammed into the aisles and lied on the luggage racks, wherever they could squeeze themselves. But after a misunderstanding, I ended up in the section for party functionaries, sitting on overstuffed velvet seats. I saw how the other side lived. And I started to ask myself the foundational moral question of: who decides? Who decides what we get, how we get it, what it costs, whether or not we can afford it?

A few years later, working in Marxist Ethiopia, I encountered remarkable women traders who paid no heed to the nomenclature of their nation’s regime — they traded to survive. I’ve worked in both capitalist and socialist nations, and I’ve learned that most people want to solve their own problems and make their own decisions.

Those early experiences wearied me of conversations that assumed our only choices were unbridled capitalism or pure forms of socialism. Both tend to make the poor invisible. Both allow the privileged to hide behind abstraction and cynicism, and ultimately reinforce the status quo. If we want to solve our biggest problems, we need to focus on the realities of low-income people, and build from their perspective, using capital as something we control, not something that controls us.

So for how markets fit into your work, first in what ways do markets tend to produce much more concentrated vulnerabilities and opportunity gaps than strident free-market advocates care to recognize? And at the same time, how can well-functioning markets benefit impoverished people around the world — by catalyzing entrepreneurial agency, and by operating as a “listening device” through which long-marginalized communities make their own true needs known?

I come at this from having seen, for decades, more traditional top-down aid-providers too often treat the poor as passive recipients of charity, and make decisions based on what these providers think low-income people should have. Markets, on the other hand, when used for good, position low-income people as customers making their own decisions. Effective entrepreneurs pay attention to customers’ preferences, to what they most value, and what they can afford. Entrepreneurs have to work hard to earn the trust of low-income customers. Of course, markets also can overlook or exploit the poor. And markets are limited — to bring affordable healthcare or education to very low-income people will require partnership with government. But here too, we’d do better by consulting people, without just imposing our solutions from above.

What’s needed is a long-term customer-centric approach in low-income communities, taking the time to understand people for who they are, and to structure solutions that meet their actual needs. That’s where markets can serve as a listening device. I mean, think of what happens when your great-aunt gives you a really ugly vase. You probably don’t tell her to her face how much you hate it, right? But you probably also take it off your kitchen table and put it back in the closet as soon as she leaves.

But let me make a plea for nuance. While markets might listen to customers, they too often ignore altogether the voiceless: the farmers who grow our food, or the earth itself. A market economy without guardrails can see workers as inputs rather than as full human beings. Supply chains that depend on people across the world can end up further marginalizing the needs and voices of the poor. Part of using markets as a listening device also requires recognizing when the market fails to listen, and making appropriate adjustments.

You describe Acumen deploying a particular type of capital, “patient” capital. Could you point towards the ongoing accountability attached to a patient investment (rather than, say, a generous handout)? And given this longer-term agenda (of first getting an operational plan right, nurtured through ongoing engagement with individual entrepreneurs and marginalized markets not primed for quick flashy results — then ideally scaled up), how does Acumen provide not only patient capital, but in fact quite persistent capital?

In Latin America, for example, we’ve adopted the strategy of using business as a tool for peace. In a country like Colombia, 50 years of civil war left entrenched problems, with communities not only isolated but lacking trust, lacking skills, lacking access. For half a century, the business of war made a few people rich. But business infused with moral imagination can heal and create opportunity, and be a means to build peace — especially if you define peace not as the absence of violence, but as the presence of human flourishing.

For an entrepreneur like Carlos Velasco to build a chocolate company in partnership both with the indigenous Arhuacos in the Sierra Nevada, and with communities in Tumaco (a post-conflict area known for coca growing, for cocaine), starting a business did not come easy. In the case of Cacao de Colombia, Carlos and his co-founder Mayumi Ogata spent four years building bonds of trust with the Arhuacos, who see themselves as guardians of the earth’s sustainability. Only then could the company sign a contract (really more of a covenant) with the Arhuacos, who finally trusted that these people would show up, share the fruits of this business, and respect their philosophy and way of life. Cacao de Colombia also operates in other post-conflict parts of the country, working with communities to ensure high-quality cacao that it then sells to buyers and retailers who value sustainability. Today, this profitable company works in five regions, regularly winning awards for the world’s best small-batch chocolate.

For us, deploying patient capital often means daring where others don’t, investing in intrepid entrepreneurs for 10 or more years, establishing trust that allows them to try and fail and try again — and in many cases to build up vital elements of a broader market ecosystem that can enable their own business to thrive. We accompany the entrepreneurs and extend our social capital too, our networks and connections. Money returned to Acumen then gets reinvested in further innovation for the poor.

As investors, we at Acumen see this approach as different from providing handouts and other kinds of traditional philanthropy. For example, given our 10-year-minimum time horizon, we better know and trust and enjoy working with this entrepreneur. Philanthropists often take a short-term horizon when giving to an organization. People working in aid organizations themselves tend to rotate geographies after a few years. Patient capital requires a longer-term commitment that is active, not passive. It requires a sense of jointly owning the problem that needs solving.

Part of that persistence may take the form of empathy, but here you describe a specific type of “muscular” empathy: “built from the bottom up and grounded through immersion in the lives of others.” Could you offer some examples of what even well-intentioned outsiders often fail to grasp about the difficulties marginalized people worldwide face when it comes to tapping a “market opportunity”?

Good question. Take the case of creating a market to bring solar energy into communities that, for many generations, have relied on kerosene as their fuel source. The founders of d.light, a solar-lighting company, started with a 30-dollar lantern, and a dream to eradicate kerosene. My team and I calculated how much people paid daily for kerosene (50 cents), and figured that it would be worthwhile for them to invest two months of fuel costs into buying the lantern, and then saving a lot of money with free energy from the sun.

But we failed to understand our customers’ realities. People making two or three dollars a day don’t have 30 dollars in their pocket to pay for products upfront. Financing opportunities were scarce. Trust was even rarer. And why should people trust in a newfangled technology, peddled by somebody they’ve never seen before? No doubt they’d watched other strangers come and go, offering underperforming “technologies” or “opportunities.”

On a less personal level, low-income communities often might look (from the outside) like market economies, but we really need to think of them as political economies, with so many distortionary forces at play. The status quo exists for a reason. In this case, poor people relied on kerosene because they could afford to pay for it on a daily basis — even if, over the long-term, the kerosene was expensive, polluting, and dangerous to the customer’s health. And even when d.light found solutions to those market obstacles, the company still had to contend with kerosene and diesel mafias, which had no interest in seeing an upstart company take away customers.

This is the reality of creating markets, where none existed, to solve problems of poverty. Every time you think you’ve made progress, at least in the early years, you hit some new obstacle. So we learned early on that we needed to use not just patient capital, but also our social capital. Frankly, all of us (investors, government officials, companies) could do more to extend our privilege, our networks and contacts, to people who are marginalized.

In extending our social capital, my team realized that we’d been limiting change by focusing too narrowly on investment. We had access to grant-providers. We had access to corporations and their supply chains. We had access to designers who could help companies like d.light do an even better job serving low-income people. We could inspire a new set of partners to employ their moral imagination and build from the perspective of low-income communities. At Acumen we define “moral imagination” as having the humility to see the world as it is, yet still having the audacity to imagine the world that could be. Moral imagination starts with empathy, but does not stop with empathy — because empathy alone just reinforces the status quo. Nothing changes. Empathy should lead to immersion, to becoming proximate to people whose problems you want to help solve. Next you need to analyze the systems that get in their way, and only then to construct solutions that will ultimately enable people to fix their own problems.

Here alongside a daunting entanglement of external deficits that might include problematic infrastructure, schools, healthcare, and legal protections, you speak delicately of a “further sense of unworthiness” that many marginalized people you’ve worked with struggle to overcome. With this internal sense of unworthiness in mind, could you describe what it looks like for patient capital to take on the interpersonal task of accompaniment?

When we started Acumen, we still used the business-oriented term “post-investment.” But we realized that sounded too distanced. We really were talking about “accompaniment,” a Jesuit term that means to walk beside. Accompaniment means that I will own this problem with you. I won’t solve it for you, but I’ll help you build the muscles to solve it yourself.

I often think back to the work of Amartya Sen (the Indian economist and Nobel laureate), to his writing about development as a form of empowerment, as a journey in which people find agency, find the capacity to make decisions for themselves. Part of this agency comes from access to markets, but access to markets isn’t enough. You need the capabilities to flourish within those markets.

When I read Sen discussing all of this 25 years ago, it made intellectual sense to me. But only by working with entrepreneurs building companies in overlooked, underestimated communities have I really come to recognize how profound Sen’s ideas are. Your company might offer very helpful solutions for low-income people’s education or healthcare needs. But your customer also has to feel worthy enough, and to build the skills and confidence to actually make use of such opportunities.

I’ve watched people pull themselves back from many opportunities. I’ve participated in judging a number of business-plan competitions, and noticed that women often seemed to hold themselves back, or ask for an unnecessarily small amount of money. By accompanying people who’ve been overlooked for too long, we can send the message: “I’ve got your back. I’ll help you take on a problem, but I won’t solve it for you. You need to do that work yourself. You need to take the lead. But let’s dream a bit bigger.”

Accompaniment is as important in the US as anywhere. Look at our healthcare crisis. Some of the most interesting accompaniment models today come from community health workers. These individuals, not specifically skilled in healthcare, are given rudimentary training, enabling them to accompany other community members, with chronic diseases like diabetes or gout. The health worker will call patients, make sure they’ve taken their meds, check their vitals, join them on walks, develop a plan to get them to the greengrocer. All of those tiny efforts combined can bring significant reductions in hospital visits, in hospital bills. Patients are healthier, hospitals are less burdened, and health-worker organizations get paid by government for reducing its costs.

The pandemic has taken a terrible toll, and brought terrible hardship. It also has accelerated the creation of new business models for a new economy. For example, Acumen investee Everytable started off in Compton as a fast, nutritious, affordable restaurant — so popular that it expanded to eight locations. On the day of lockdown, Sam Polk, Everytable’s entrepreneur, had the North Star vision to focus on delivering healthy food to people. He posted a tweet that basically said: “If you need food, we’ll deliver. If you can’t afford it, we’ll deliver it anyway. And if you’re able to pay it forward, here’s a link.” Overnight, people across Los Angeles contributed, soon enabling this company to deliver hundreds of thousands of meals to Compton residents.

Everytable (which by now has delivered over six million meals) also decided to build a university, and to accompany employees with entrepreneurial proclivities. Everytable would train them in what it takes to establish a franchise. The company is building a fund that provides low-interest loans to trained employees, so that they can afford to start their franchise. It guarantees them an annual salary of $40,000 for three years. Over the next three years, Everytable hopes to launch 40 franchises prioritizing black and brown ownership.

These kinds of purpose-driven business models insist on profitability, yet operate according to a moral framework that puts human beings at its center. We have such an opportunity in the United States. Starting from the American entrepreneurial spirit, we can build new business models and celebrate new role models based not on metrics of money, power, or fame — but on the level of dignity they enable for those who have been left out. This new American story should be all of ours.

Specifically in terms of scale, you write that, when it comes to transformational change, “small is beautiful, but scale is critical.” Could you describe some enduring challenges, and some effective strategies, that Acumen projects have undertaken when it comes to scaling up crucial human factors such as empathic listening, mutual accountability, and broadly distributed stakeholder agency?

I consider that the Holy Grail question, Andy. Acumen had its 20th birthday this month, and while our first 20 years focused on building new business models for a new economy, I sense that this next chapter will focus on understanding at an even deeper level what it means to scale our impact.

I also see more than one way to scale successfully. With electricity, for example, we’ve scaled up by using more traditional capital. We invested $250,000 in d.light in 2007. Between our nonprofit and for-profit funds, we’ve since put about 11 million more into this company. It now reaches well over 100 million low-income people, and has helped launch an energy revolution. We’ve become the largest investor in off-grid energy for the poor. The world thankfully now has a constellation of off-grid energy companies seeking to address the fact that 700 million people still have no electricity, which just shocks me (since Thomas Edison invented the lightbulb 145 years ago). So that’s one path to scaling investments.

But sometimes you need to scale up a whole institutional or infrastructure ecosystem, with individual contributions and individual companies eventually coalescing into collective action. That’s an important piece with energy, for example, where we face problems too big to just figure out by ourselves. Or sometimes you need to scale up by building much more inclusive supply chains. With commodities like cocoa and coffee, our companies have developed robust business models that pay low-income farmers living wages, rather than keeping them stuck as “price takers” — accepting whatever price global commodities markets offer that day.

And then an additional path to scale takes the form of a collective mind shift, a cultural shift which might require the most effort of all. This pandemic (not our last pandemic, by any stretch of the imagination) shows us the economic and political divides we still need to overcome. These cultural shifts require us to move beyond putting the profit-oriented individual at the center of our social systems. We need to put our shared humanity, and our collective dignity there. This kind of mind shift needs to happen in the private sector, in government, in our politics and civil-society and nonprofit sectors.

How about for Acumen itself seeking to blend generosity and accountability, humility and audacity? Which internal dynamics have helped for finding and maintaining the right organizational balance in these terms? How does Acumen go about living out its own values? And along the way, how do you see Acumen modeling these values?

Avoiding any single bottom line isn’t easy. Combining the interests of purpose-driven enterprises and profit-minded shareholders requires holding competing values in tension. No roadmap existed for us. So we realized we needed a moral compass, one that laid out the foundational values by which we would make decisions. We wrote Acumen’s manifesto as an aspirational document, knowing we’d sometimes err, but then would course-correct.

From its start this manifesto pledges to stand with the poor, listen to unheard voices, see potential where others see despair. But still our investment committees always include people who have worked at traditional investing firms. These committee members will long ago have gotten used to pursuing a single bottom line of maximizing shareholder value. When first encountering our model, they usually will raise questions about the manifesto’s language. We’ll have conversations asking what it looks like to use investment as a means, not an end. We’ll talk about why our capital needs to go where others’ capital will not. We’ll discuss the long-term nature of these investments in innovative companies designed to solve a problem that hasn’t been solved, or to create a market where none existed.

Acumen has stumbled when we’ve overreacted to the pressure of investors or philanthropists, to an emphasis on financial returns over social returns. In those moments, our manifesto helps us to re-find our North Star.

Maybe most specifically for your own role at Acumen, could you outline some of the ethical principles, the strategic thinking, and the painstaking research that go into investing in character?

First, there’s nothing like doing the work you love with people you love. And second, early on we learned that when we failed to invest in character, our investment often failed. Young entrepreneurs working in corrupt systems face so many tough challenges. They might come from families who have honed a business-as-usual code for cutting corners, paying bribes, and doing what it takes to win. The pressures might come from communities that value honor more than honesty. But those strategies will fail us in our long-term goals.

By contrast, investing in character pays off. We’ve seen entrepreneurs not just build companies, but help to build their nations. Sam Goldman and Ned Tozun, the founders of d.light, have done that. Acumen investee Jawad Aslam has built housing for the poor in Pakistan, in ways that only can happen when directed by individuals equally talented in head and in heart. These entrepreneurs understand business. They know what it takes and they have the rigor to build something financially sustainable, driven not by a sense of personal gain but by a commitment to give back — to reach more and more low-income people, to give communities access. But they often have to fight the status quo along the way, which also means learning to play hardball.

People look at the work we do, and hear me describe it in poetic language, and might think of us as soft. But beneath that softer tone is tenacity and toughness. Our investments in character take all of this into consideration. We have an established reputation for integrity. People around the world trust us. All of that matters. And these investments in character also play out in who we hire, in how we hire, in doing a different kind of due diligence than simply being enamored by an entrepreneur’s business plan or a great idea or a cool technology.

For my own investment in entrepreneurs’ character, I ask myself: has this person had to learn from failure before? Has this person cultivated resilience? Does this person help others around them to shine, or do they keep all the attention on themselves? Can this person hear feedback and actually make good use of it? And finally, especially challenging at this moment of history: can this person partner with people across sectors and across lines of difference, even if they disagree with parts of what their partners stand for? We all need to build up those skills. We need to exercise those muscles and develop the strength to reimagine the systems around us, in ways that include and benefit everybody.

Okay, that takes us to the tricky task of defining moral leadership — not as a moralizing imposition on others of course, but as an honest reckoning with the truths that we can come to embrace in perspectives supposedly opposed to our own. Could you sketch a couple case studies of Acumen investments that would have failed if not for investees’ exemplary moral leadership?

Oh, so many come to mind. I’ve already mentioned, for example, Jawad, a Pakistani American who grew up in Baltimore and worked in commercial real estate, and wanted to do something for his parents’ country. Jawad moved to Pakistan shortly after 9/11, and immersed himself in working in slums with one of the master-practitioners of low-income housing. He then decided to create not just his own affordable-housing development, but Pakistan’s first for-profit mortgage company for low-income people.

From the get-go, everything stood in the way of success. There was a reason no mortgages ever had been made to low-income people in Pakistan. Then early on, after having secured the land (a feat in itself), Jawad was told that he’d have to pay a small bribe if he wanted to register this land. Jawad refused to pay that bribe. I remember him coming to me a year after he first tried to get this land registered, and saying: “I’m so embarrassed. I haven’t even dug a spade of dirt.” I’d say: “Jawad, our capital is patient.” After 18 months, Jawad ultimately secured the registration through legal means. We helped make the right kind of noise. The government actually set up a new unit that worked to ensure people could get their land registered.

Then came the next challenge. Little trust existed to convince marginalized communities to buy into Jawad’s idea. So Jawad built this beautiful demonstration house. I remember going to see it, and just loving it. And it’s a long story, but we got caught in the crossfire of a very hairy shootout that night, very visible to all of the nearby villagers. About 50 young guys came at us from both directions shooting guns. But the next day Jawad went back, and displayed again great moral courage, and signaled to people who for generations had been taken advantage of that this time was different.

He soon built a house for himself in the development, to get to really know the residents and their lives. I have story after story of how Jawad combined true generosity and true accountability. He had to build something that had never been done before, for people who had little reason to trust him, and who had very little money. He didn’t want to evict anybody, but he also needed to show that he was serious — because without financial sustainability, the project would fail. And not only did he end up selling half of this company for a significant amount. He can take this model across the nation. He now sits on the prime minister’s housing commission. He has influence on policy, and can assist with scaling up, both within Lahore (the community where he started), and in a broader realm of ideas.

So could we now flesh out the “new narrative” this book calls for, a narrative that eschews silver-bullet technological or market solutions to entrenched inequities, a narrative that pushes beyond “peaceful coexistence” by positing proactive commitment to each other’s well-being, a narrative not of top-down policy dispatch — but of “moral revolution”?

Well, I use the word “moral” not to mean righteous. I actually mean the antithesis of that. For me, “moral” means moving away from focusing solely on the individual, or on some sense that I am right because I know you’re wrong. The word “moral” means a focus on the collective, on a sense that creating more for you also creates more for me — particularly when it comes to dignity for all, to each of us being valued for our contribution to building this future we will share.

That kind of moral revolution can’t come from “above” or “below,” but necessarily has to come from within each of us. As a young person, I would have loved to think that one sector could take on the responsibility for another. But after having done this work for 35 years, across all sectors and scores of nations, I’ve concluded that we only can solve such big collective problems if we reimagine, revitalize, and renew our institutions, our companies, our political systems — and frankly, our civil societies.

Today we have ample opportunity to do all of that. COVID has shown us how truly broken these systems have become. But hopefully, that also breaks us open to the idea that only when we combine our compassionate side with our competitive side, our heart with our head, purpose and profit, can we serve as foot soldiers in a moral revolution that does not moralize, that has the wherewithal to make us better understand one another, to recognize that we need the widest variety of perspectives — and also need to find our way to common ground. Building that sense of wholeness, which encompasses all of our diversity, is not easy work. But it’s work within our capabilities, and it’s the work we have before us.

Here you could think of how tough we are today on people who lived one hundred years before — on what they did right, what they did wrong. I’m sure that, one hundred years from now, people will have many reasons to see our moment in history, our generation, as less than perfect on so many fronts. But I hope most of all that they can see we tried, that we held onto that hard-edged hope, that we used whatever tools and skills we possessed, that we didn’t turn away from the opportunities and possibilities, and also the responsibilities we had to one another.

Moral revolution of this sort might sound completely separate from government. But within a foreign-aid context, how could US government help to foster dynamic local enterprises — as well as more effective public-sector support for the poorest people in the poorest countries?

I actually think that the practices and principles articulated in this book can apply to government just as much as to the private sector. My own work might have started by treating markets as listening devices, and bringing more accountability to what I saw basically as a broken aid system. But over time I’ve also seen that when companies scale up, particularly in healthcare and education and certainty safe drinking water, partnership with government often becomes critical. I sense that these types of private-public partnerships will be increasingly central. But we need to learn to partner with a deep measure of humility on all sides, with each partner honest about its own distinct strengths and weaknesses.

So do I see government playing a useful role in fostering an environment for small-scale solutions-oriented enterprises to flourish, and to keep expanding? Absolutely. In the US itself we have a bill under consideration right now to support small-enterprise development at home. But any such support for disadvantaged entrepreneurs should consider the systematic racism in our nation, and contain a significant accompaniment element, one that extends social and not just financial capital to overlooked communities.

Partnership is the only way we’ll build more inclusive economies. Every dollar of philanthropically backed patient capital that Acumen invests in poor communities is leveraged four to six times with traditional investment. So with the $135 million of philanthropic capital that Acumen has invested, we’ve moved almost a billion dollars into markets that, for the most part, didn’t exist before we invested. But that leverage would not be possible without philanthropists stepping up. And the companies would not scale without support from investors, corporations, and sometimes governments.

One of Acumen’s government partnerships that makes me proudest is with USAID in Latin America. USAID has provided significant grant funding so that we can invest in companies like Cacao de Colombia, and do the work of addressing post-conflict communities’ lack of trust, skills, access, infrastructure — and also the dependency created over too many years of too much aid. The results speak for themselves: not only jobs and opportunities and a growing entrepreneurial ecosystem in Colombia, but a shared sense of ownership (and, I dare say, dignity) between the team members of Acumen and USAID.

On a somewhat similar note, why does anyone seeking to alleviate the damages inflicted by systemic poverty today need to care deeply about climate change?

It goes without saying that climate change disproportionately impacts the poor. In 2010, we saw 20 million Pakistanis displaced because of floods caused by melting ice caps and Himalayan deforestation. During COVID, Kenyan farmers have had to deal not only with a health emergency and collapsed markets, but with droughts and floods and a locust plague destroying crops. Across Ethiopia, droughts have lasted multiple seasons, with farmers unable to hold onto their livelihoods. In Rwanda, coffee farmers tell us about the coffee trees’ confusion: having new flowers, young berries, and mature cherries all at once.

Consider that there are 2.4 billion smallholder farmers, and that this group accounts for half of the world’s people living in poverty. And in 2020, another 20 million people were displaced because of climate change. Where do the displaced go? If we do not help solve problems in ways that allow people the dignity of choice and opportunity within their own nations, we will all lose. If I’ve learned anything it is that we don’t get dignity as a human race until we all have dignity.

So at this moment of many nations turning inward and telling themselves: “We need to take care of our own, so we need to push away these refugees and immigrants,” I’d stress a more constructive combination of urgency and patience. I’d stress envisioning a longer-term horizon, recognizing our interdependence. All of that makes this climate crisis, and how it affects poor people, everybody’s problem — just as we need to get vaccines to the poorest people on the planet. The world can’t solve these problems without solving them for, and with, the poor.

Finally, for your own lived experience within this absorbing (and at times no doubt exhausting) field, could you describe the sustaining force you’ve found in finding beauty — everywhere, in some form or other?

Right, we don’t discuss this enough when people sign up for lives of change. But that kind of long-term commitment gets exhausting at times. You can see problems that probably will stretch beyond your own life. Some days you just don’t know how to sustain the effort.

When I returned to Rwanda after the genocide, when so many friends had been murdered while others had been bystanders or even perpetrators, I remember wondering how I’d ever get through some of those nights. Yet at every step along the way, including some of those horrendous and unforgettable conversations, you can find beauty.

Sometimes it manifests physically in the meanest, ugliest slums. You’ll see women decorating their homes with such pride, planting geraniums in coffee cans, or hanging lacy curtains in the windows of tin-roofed shanties. You’ll find such unexpected beauty in how people cultivate their lives and their hopes — or how they create song and dance to help endure cruel hardships. I’ve come to recognize this beauty as an urge to life, as a way of survival. I come across beauty like this wherever I go. It may show up in a deep sense of sheer human connection across so many boundaries and barriers. It finds you even in the most unpromising places. And especially in those places, it often reflects back to you the best and possibly the most beautiful parts of your own self.