What should you do when your lyric investigations of secular uncertainty start echoing a rhetoric of religious rapture? What might a non-affiliated poetics of spiritual striving look like on the material page? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Joshua Kryah. This present conversation (transcribed by Nicole Monforton) focuses on Kryah’s collection Glean. Kryah, also the author of We Are Starved, lives in St. Louis and teaches at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville. He has received fellowships from the NEA, MacDowell Colony, and the New York Public Library, and his awards include the Michael W. Gearhart Prize from The Southwest Review and the Third Coast Poetry Prize.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with the Dickinson epigraph? I love to think about Dickinson as an erasure poet before her time, so could you parse here Dickinson’s distinction between what it might mean to “annull” rather than to “discontinue” oneself (or, perhaps more specifically, for God to choose between those options)?

JOSHUA KRYAH: That quote actually came to me in this somewhat arbitrary way. I didn’t seek it out. I wasn’t spending serious time with Dickinson’s work. I mean, I had always been reading Dickinson, but I was decidedly involved with a bunch of other poets at that time, especially someone like Paul Celan.

The composition and publication of Glean kind of all happened together, and that was a pretty important aspect of publishing with Nightboat. They gave me great liberty to do almost whatever the hell I wanted. So this Dickinson epigraph came a bit later in the process. There’s often this pressure and anxiety, with a first book of poems, to present yourself carefully. You want to be smart. You want to be taken seriously. You want to designate a predecessor or the company that you keep, or that your poems keep, and to let your reader know that immediately.

But for the Dickinson quote, I was finishing up in grad school, and taking a class where we had to choose an author to research, and edit, and create a sort of pseudo-anthology of poems by, or a critical text of essays about or around. I was doing an Objectivist anthology, so working with Reznikoff and Rakosi and Zukovsky and Oppen and Niedecker and a bunch of other folks. Another student was working on Dickinson, and we at some point happened to be talking about our projects, and somehow this quote came up. It came from one of Dickinson’s jottings, one of her scraps of paper somewhere that my colleague had found. I think she had a ditto copy. I saw the quote and felt immediately arrested by it. It seemed to speak directly to this project I was immersed in, to the writing of Glean — to thinking about ideas of belief and doubt, of what kinds of trust anyone might have in faith or in God or in a god.

I was especially drawn to the part you just asked about, where the statement gets crossed out and erased. There is some hesitation here, and not just in the writing or composition, though that’s part of it. Dickinson is editing herself as a writer, but also as a spiritual being, and that’s what I found so compelling. Even without much context about Dickinson and her biography and her great array of poems, you can physically see in the quote this inclination to annul or discontinue — which is always there, and yet you can’t do it. You could (but cannot) get rid of your belief in something. And you can sense here how this desire to believe in something is both appalling and frustrating, but also comforting and magical and wonderful in many ways. In the actual handwritten note, you can see the word “discontinue,” with the word “annul” still underneath it. Dickinson just crosses through that word with one little mark. Whether she intended it or not, for me that does feel intentional.

And for me that annulment just can’t go away, again even though the impulse to do so is there. You might try to get rid of any doubt. Or you might even try to abandon your faith, because it causes problems. It makes you uncomfortable. Certainty or uncertainty both can feel like these absolute states impossible to endure or even to attain. So yes, I did feel a sort of connection with this moment that Dickinson seemed to dramatize in her own life. Again, contextually, I don’t know what this particular statement of hers might have been about. I’m not very knowledgeable about Dickinson’s ideas of faith or grapplings with faith. But this one snippet seemed to distill those grapplings for me, and for my own book. Glean’s poems enact something similar again and again and again through their composition.

I’ll often sense a continuum of shame and exhibitionism in Dickinson. And amid your own work, amid the complex and generative role that uncertainty plays in Glean’s poetics, does any lived trajectory stand out for how you arrived at this realization that uncertainty would saturate the book’s content, structure, tone?

It did take a while to get to that point, that level of understanding where I knew what was happening or what was being addressed again and again in these poems. Of course something similar always happens compositionally — as you write one new poem and move onto the next, and then begin to assemble these poems, begin to gather them and make connections revealing to yourself that Oh, this is happening. I didn’t quite understand that overall process at first, but those connections (thematic or otherwise) that I wasn’t initially aware of, or wasn’t paying much attention to, started to stand out.

It started to become clear, for example, that these poems weren’t about just any uncertainty, but specifically an uncertainty of belief and of faith. Again that didn’t surface immediately. I was not a faith-based poet. I wasn’t constantly writing about those issues. I was addressing a more general uncertainty in life or in one’s experience, but much more in a romantic mode — pitched towards the “you” as the beloved, the “you” as my Beatrice. Early on the poems seemed directed towards a more specific, romantic, engendered figure. But as I kept writing these poems, that figure became increasingly elusive. There was no one I was actually writing to, in terms of some sort of lyric gesture. There was no Beatrice I was directly addressing. So after a while it became more exciting to ask questions like: who is this “you”? Who else could this “you” be? How can I complicate it more? How can I broaden it? Where else does this uncertainty and anxiety of uncertainty come from, aside from being lovelorn or being alone and not with a partner of some kind?

Again I’m not necessarily affiliated with any one religion. I have a Catholic background which is definitely still with me in some ways. But I’m not a spiritual person in that sense. So these developments with the book did take me by surprise. I didn’t know why I was moving in that direction. But I was reading things at the time that probably helped, like Celan and Gerard Manley Hopkins of course. I was reading John Donne and many folks who had some sort of spiritual element to their work, even though I didn’t identify with this particular end, this entity, this God, this presence. But the state of uncertainty that these poets experienced in relation to God did feel very familiar.

So I began to turn myself in that direction. I began to read more religious texts, the Old Testament and the New Testament in particular, and just started finding very compelling elements helping me to translate what I was feeling and wanted to say. So that sense of uncertainty really did start to shift inside me. This doubt in the belief in something, this wanting to believe in something but not really being able to, or not allowing myself to — that tension, that struggle in the poems became very apparent and available, and felt very generative. That compositional tension for poems felt very compelling. I kept coming back to and struggling with and wanting to figure out how to resolve that sense of doubt, but also to try to get at it in different ways in different poems. And this didn’t let up for quite a while, for the entire manuscript. I mean, all the poems began to go in that direction.

This idea of uncertainty began to clarify in another idea of vulnerability. I had to admit to myself a great anxiety before any certain faith or belief system, whether theological or just more personal. But that’s still a very uncomfortable place for me. And I also didn’t want to take the approach of being sarcastic about these doubts and vulnerabilities. And then, over time, I eventually felt like I had exhausted this one particular approach. For that whole sense of uncertainty (especially in the context of faith and doubt and spirituality) as the premise of these poems, I do feel like I kind of got that out of me by the end of this book. I still return to it in some more recent poems, but it has really changed and shifted. I feel like I kind of worked through some of that.

Well as you just described this lived transformation, I realized I had projected something of a reverse trajectory for the book. You mentioned moving from a romantic-infused poetry to a spiritual probing, whereas I had sensed a momentum in Glean from dwelling in a state of uncertainty, to acknowledging one’s vulnerability, to discovering the possibility for some sort of erotic relationality or connection or communication. From “Called Back, Called Back” to other opening poems, the more sexualized the tropes become, the more “swelling” or “keys” that appear, the more that lines like “caught between monad and many” also stand out. Some of these lines suggest a sense of guilt, or sometimes a sensation of pleasure found in a recognition of a sexual differentiation and / or a sexual co-dependency. And my lack of religious training leaves me forever ignorant of, yet intrigued by, Christian metaphors of the bride and bridegroom. And Glean offers its “I’s” resemblance to a bride with “half-turned face,” which obviously recalls Eurydice and Lot’s wife. So could you say more about how gendered relations might provide a useful entry into this book’s twinned erotic and otherworldly pursuits?

At a basic level, that all seems pretty Metaphysical, right? It points back to someone like Donne, and his yoking together of the spirit and the body. Or again, for my own personal experience, that all comes both consciously and unconsciously from my Catholic background. The Catholic Church is always reminding those who participate in the faith of these sorts of dualities and tensions. The church asks you to take in the body of Christ and the blood of Christ, but it also asks you to forget the body. It tells you your earthly sins are nothing compared to the pleasures of the heavenly paradise that will come later. So there’s this wonderful tension and contradiction and very palpable struggle. And even going to mass itself is very physical, with all the sitting and standing and kneeling. Then at other points you actually turn to your neighbors and offer them peace and shake hands or hug them.

So here Donne and Hopkins were very much at the forefront, as authors I felt this strong affinity with while writing Glean, and as authors whose struggle with faith is also a struggle of the body. Their struggles show us that the body itself has great promise but also experiences great failure. To believe in this body completely is itself a risk, and involves a lot of vulnerability. When I was writing the poems, while thinking about Donne and Hopkins, I was very cognizant of how the body fails again and again, just like one’s faith fails again and again. I kept making that connection to how the body fails naturally, for the most part. It used to be full of hope, but it naturally declines. It naturally falls away. It cannot last. It cannot stay. So what about faith? Does faith naturally endure forever? Does it just go on forever, or does faith also present a similar risk, something you can abide by, but something you can’t rely upon — something you can embrace and can feel, but which still risks dying, faltering, abandonment?

Here also, in terms of Glean’s erotic elements, Donne provides a great example, as someone initially not writing as a religious poet, but as a very physical, erotic, court poet — writing about politics, about the world, about advancements in technology, but also writing about his lover in very (for that time especially, but even now) explicit poetic language, very physical, very sexual. The beloved Donne addresses at first is this romantic, erotic, sexual figure, and then it becomes God. It becomes Jesus. There’s something very dissonant and uneasy about that, and yet in the Catholic tradition that’s very familiar.

Hopkins does something different. He’s speaking to God from the start. But he’s also speaking to a spiritual presence in this very physical way. He’s manifesting again and again this spiritual presence in a physical or poetic form — as if to substantiate that his faith is worth something, that his own bodily denial as a priest can be rewarded by another kind of intimacy that he’s otherwise not finding, or is still looking for.

And of course, as you suggested, there’s also this idea of nuns as married to God, to Jesus. They remain celibate because their husband is literally Jesus. They are God’s brides in this way, but at the same time they’re denied or not allowed any real physical intimacy with another human being. They have this partnership with one another and then with their God.

Those various erotic aspects always seemed so available while writing these poems. And St. Augustine also, in his confessions, states (right away this is how he talks about his own life) that he was a layabout, that he loved the flesh, the drink, and all of this. Then he has the conversion and he changes. Then he becomes celibate, but he doesn’t forget what came before. Augustine is always reminding the reader: “Hey, I used to do this.” He knew it, and he knows it. He had that physical sexual experience and then he sort of, really aptly, just grafted it onto the spiritual life. He never says “That didn’t happen,” or “I disavow all that.” He just accommodates it. He brings it over. He says: “Well, I no longer adore physically this woman or this person, because instead I want to know God that badly, that much. I want to get that close to him.”

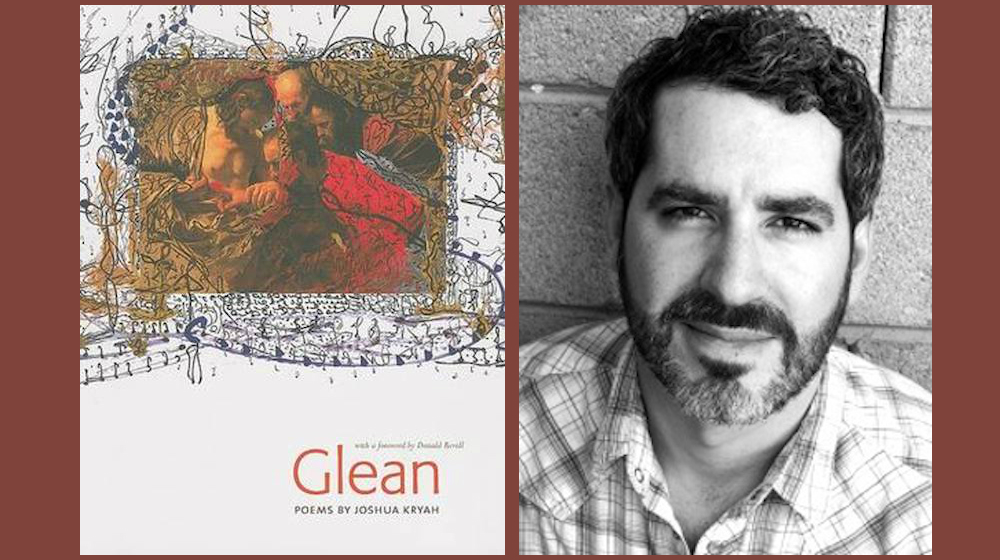

That’s also why references to Doubting Thomas appear throughout Glean, and why the book has that Caravaggio painting on its cover, with this incredibly intimate moment of the physical body meeting the spiritual. So yeah, someone could read all of this sexually. That’s part of the project, I think, in these poems. The poems don’t want to disavow that possibility. They don’t ever say it has to be one or the other. That basic (sort of impossible) tension is what I still go back to when thinking about these poems. That’s something I still can feel as a poet and as a person.

The Caravaggio painting also shows that some of this tension is homoerotic obviously. That’s something various cultures have developed in relation to adoring this Christ figure, but adoring him in positions of debasement and vulnerability, and positions of being cut or slashed or marked or dead or crucified — all of which tend to further complicate questions like: why are we venerating the violence done to this body? Why are we paying so much attention to how this body is susceptible to these slights of age, or from other people, or from itself?

Again all of that seems to counter-balance or somehow to upset any more pure, austere conception of spirituality here. The pure aspects are further away. They’re not attainable. They’re over there somewhere. But locating them within the body can substantiate them in a way you can’t touch up at the altar, or up in the heavens. So I was trying with these poems to convince myself that the body might be able to substantiate its physical desires, needs, and failures, as well as its spirituality — that those two drives are the same. They both fail. They both have needs. They both have desires. They’re both, as Donne said, yoked together in the same person, the same place, the same body.

I hope the poems themselves show evidence of this tension, this violence, this struggle — evidence of their own vulnerability, because the poems are not perfect. Some of them don’t make sense. Lyrically they’re a bit off-base. That’s again more evidence of breaking apart the body and the bones of the saint, and beginning to scatter these around and let people do what they want with them.

I also was paying very explicit attention not just to how I was writing the poems, but to how they looked on the page. Especially when I could put the full manuscript together, I really wanted to pay attention to how the body of each page and of the entire book itself looked, and how someone might navigate it or move through it. The titles themselves try to display this struggling with what they’re saying. They sometimes have parentheticals. And then other voices or echoes or typographical elements might start speaking back and interrupting the poems. We don’t always know whose voice we hear, who the author or speaker is. Is it a quote? Is it a conflated quote? Is it a made-up quote — what is it? It’s just not very clear, but things continue, and each text sort of comes and goes out, comes and goes out. Again I want to show that whole process of not turning away from the difficulties of composition, or that complicated gesture of both writing the poem and turning the gaze back onto it, so that the poem becomes my own kind of bride. I am wed to it, but with that union comes difficulty and challenge and not always harmony.