Which foundational-seeming American values, norms, and freedoms actually come out of progressive fights from the past century? Which of these inspiring precedents can serve as the basis for a dignity-of-work political vision today? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Senator Sherrod Brown. This present conversation focuses on Brown’s book Desk 88: Eight Progressive Senators Who Changed America. Brown is the senior United States Senator from Ohio. He was the US Representative for Ohio’s 13th congressional district from 1993 to 2003, and Ohio’s Secretary of State from 1983 to 1991. Brown began his political career in 1975, upon election to the Ohio House of Representatives. He lives in Cleveland with his wife Connie Schultz, a Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist and author.

¤

ANDY FITCH: To flesh out a bit your “dignity of work” political vision, what would you consider some most pressing priorities for a dignity-of-work platform in 2020? Where have you seen such priorities best represented? Which most crucial parts of such a platform haven’t received much attention at all?

SHERROD BROWN: Well in this presidential campaign we’ve seen a sharp contrast between the two candidates’ very different views of work. During the Democratic Convention, the term “dignity” came up time and time again. Joe Biden himself, many Biden supporters, and various everyday citizens mentioned this idea often. And honestly, I think Biden speaks to the dignity of work more directly and more genuinely than any presidential candidate (Democrat or Republican) in the past generation. He campaigns through the eyes of workers, whether you punch a clock or swipe a badge or work for tips or raise kids. And I’ll leave it to our readers to contrast that with Donald Trump’s consistent betrayals of working people’s dignity.

One reason this word “dignity” means so much to me has to do with how Dr. King talked about the dignity of work. The first reference I can find to this phrase actually comes from Leo XIII (often called the Labor Pope), at the turn of the 20th century. But King spoke often about the dignity of work, and its fundamental overlap or interconnection with civil rights.

When you grasp that connection, you understand the arc of Dr. King’s own life better. In one of my favorite examples, King describes the street sweeper who should “sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music, or Shakespeare wrote poetry…. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.” Every day in this office, I fight for that sense from Dr. King of how an adequately paid job and the dignity of work make our democratic project meaningful. Similarly, while none of the Senators my book explores used this “dignity of work” phrase with any regularity, they all started from the basic principles that work has dignity, and that workers have value — and that if government lines up alongside workers, and employers pay workers a decent wage with decent benefits, you have a much better society.

Could you lay out some further ways in which today’s fight for the dignity of work overlaps with long-standing demands for racial justice and gender equity? I understand, for example, the demographic limitations you faced in selecting case studies of progressive 20th-century Senators. But how do you see this book speaking to a quite diverse range of present-day progressives, whether or not finding themselves immediately reflected in these white male predecessors?

Right, I mention in this book’s prologue that everybody who has held (or at least signed) my current Senate desk seems to have been white, male, mostly older than 50. I write about my hopes that, over the next 50 and 100 years, many more progressives will hold this desk, with many of them women and people of color. The 2018 elections make me especially optimistic about that.

The book took about 10 years to write. And it wasn’t a book from the start. At first, it felt more like a reading project. Thinking about this desk’s history meant thinking about the Senate’s history. Looking at all those signatures on the bottom of Desk 88’s drawers, I gradually traced together this progressive string of names. Given our Senate’s history, that mostly meant white men — though of course progressives themselves have always been more diverse than that, and thankfully the Senate has started changing.

Your book also does an admirable job sketching seemingly foundational American values, norms, freedoms, protections, and institutions emerging directly out of work by these progressive fighters from the past century — facing endless accusations of class warfare and apocalyptic socialism, simply for trying to reduce child labor, or provide a lifeline for families subject to potentially lethal economic dislocations. So picturing a canary pin on your lapel right now, where can progressives gain the most clarifying and empowering perspectives by realizing how much of our collective security, dignity, and prosperity realized over the past 120 years (with almost no precedent in human history) comes straight out of those fights?

Progressives don’t often win across the board. But when progressives win, we do really big things that benefit society for generations. Much of what makes Americans most proud of their country in 2020, or made them proud in 2010, or in the decades before that, came out of our 20th-century progressive movement. Big progressive wins in the 1930s brought collective bargaining and Social Security to the country, and electrification to our rural regions. Even with ongoing racial and gender discrimination, progressive reforms still made everybody’s lives better and richer. Our national-park system, our various forms of worker protection and social insurance, all come out of that legacy.

During the Lyndon Johnson presidency, with strong progressive forces also in the Senate and House, the US then established foundational civil rights, voting rights, access to Medicaid, to Medicare, to Head Start. Congress passed and the President signed the Equal Pay Act, the Higher Education Act funding Pell Grants, the Wilderness Act — and again our whole society benefitted. Many of today’s institutions that best define our American values, that give us some sustenance in our public spaces, came out of those progressive victories.

Just think about how much individual Americans, and American society, have depended on our unemployment insurance since March. Until the Republicans let it expire in August, expanded unemployment insurance during COVID kept 12 million Americans out of poverty. We built that amazing assistance program directly on top of progressive Rooseveltian social insurance, in this case unemployment insurance. And again, in terms of Senate history, that all came out of these eight Senators and many of their fellow progressives keeping up the pressure throughout the past century.

Tracing those historical cycles helps to make concrete another of this book’s basic interpretive principles, eloquently formulated by figures such as Hannah Arendt and Coretta Scott King in Desk 88: that progressive change happens unevenly, primarily through concentrated bursts, followed by much longer periods in which entrenched interest groups regain the upper hand, rolling back progressive policy wherever possible. Could you speak to your own lived experience of these exhilarating glimpses and long-term slogs that progressives should understand as perhaps an inherent part of their work?

Personally, I’ve found this all easier to see in retrospect. FDR and the Democrats had really goods elections in 1932, ‘34, and ‘36. Almost never in American politics does the same ideology win big for three consecutive election cycles. Johnson had a great year in 1964 and a bad year in ‘66. Obama had a good 2008 and a terrible 2010. But I don’t see a lesson here that if LBJ and progressives hadn’t overreached in ‘65, they wouldn’t have lost in ‘66 — or the same for Obama’s presidency. Instead, I see us failing in those moments in two crucial ways.

First, we failed to give American voters immediate proof that progressive policy changes improve their lives. With Obama’s 2008 win, for example, we were able to save the US auto industry. We helped create millions of new industrial jobs. We passed Dodd-Frank. We passed the Affordable Care Act. But by November 2010, the benefits to people’s everyday lives from these important achievements hadn’t yet arrived. We always should offer some big improvements that Americans feel right away. For instance, in 2021, we should immediately pass a significant minimum-wage increase — to start making up for more than a decade with a stagnant minimum wage. We should reinstate the Obama administration’s overtime rule, which will provide, in my state alone, one hundred thousand people with higher pay. We should establish voluntary Medicare buy-in at age 55. We should make sure Americans can soon say: “I’m already better off because I voted for Joe Biden and Senate Democrats in 2020.”

Then for a second basic lesson, when we do have the institutional advantage, we need to do better building up our political muscle. Now, Republicans might try to gain political muscle by cutting muscle away from working people, by stripping away voting rights, by attacking labor and trying to decertify labor unions. But Democrats should build political muscle in a different way. We should take those policy steps I mentioned to improve people’s health and economic well-being. We also should pass the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act to restore voting rights. We need to focus on both economic dignity and racial justice right away. We need to make clear to Americans who have been ignored or overlooked or discriminated against that we’re on their side, that we’ll work hard to boost their power commensurate with their numbers — again both as voters with guaranteed rights, and as workers with a bigger say.

Then for one last broader question, I very much appreciate your personal embodiment of progressive governance representing the interests of the vast majority without much wealth and power, while letting the wealthy and powerful fend for themselves. Does this political vision inevitably mean that the wealthy and powerful will view such modes of government antagonistically? Can this antagonism never be avoided? Should progressives welcome the hatred of concentrated capitalist powers, as FDR famously did?

Well I’d never put all people of wealth and power into the category of those who stifle progressive change. I see individuals, even in a specific economic class, as a much more diverse and variegated group.

Just look at my book’s Herbert Lehman chapter. Here you have one of the richest Americans of his day, but with so many of the most powerful interests lined up against his attempts to support working families. Similarly, in our own time, when you push for progressive politics, you can expect the tobacco companies, the drug companies, the gun lobby to come out against you. Or some of the haters dislike my positions on gay rights and civil rights. Sometimes that’s not so directly about money. But in any case, I just know these various groups will line up against me, and against other progressives. I also do think about FDR welcoming the hatred of financial powers that way. Many people with wealth and privilege definitely want to hold onto it.

I first won a Senate race in 2006, a year pretty good for Democrats. The incumbent, Mike DeWine, was a nice-enough guy, who got the Iraq War all wrong. And I knew that, in 2012, these interest groups would come back at me hard. They’d go after my voting record. But I thought: I’m not going to “move to the center.” I’ll make my stand as a progressive fighting for workers. That’s always been my approach.

In the book, I offer an anecdote from right before the 2000 election, at the Ford plant in Avon Lake, Ohio. During a break in campaigning for the House, I was sitting in the cafeteria with some plant workers. Everybody except one told me they’d vote for Gore. The one Bush supporter said: “Well, Gore wants to take my gun.” And the guy beside me put his hand on my shoulder and joked: “Brown wants to take your gun, too.” And the Bush voter said: “Yeah, but Brown fights for me.” So I know my position on guns won’t get universal support across Ohio — not even close. My long-standing support for marriage equality, and for women’s right to decide on their own healthcare, won’t endear me to every Ohio voter. But I’ll still fight for every single Ohio worker, and at least some voters with different cultural values can appreciate that.

So now to start extracting specific life lessons for 2020 progressives, by sifting through Desk 88’s life studies of 20th-century progressives, could we begin with Hugo Black? Most basically here, Black’s life offers two cautionary tales: for ambitious young politicians willing to tap deeply reactionary public sentiment in order to ingratiate themselves, and for progressive purists who might morally disqualify one of their strongest, most tenacious, most enduring (it turned out) spokespeople. So what kind of case study might Senator (and then Justice) Black’s legacy offer in how a fiercely committed progressivism nonetheless should leave some space for second chances?

I’ll start from a point made by Eric Sevareid, a commentator for Walter Cronkite’s newscast during the 1960s and 70s. Speaking about that era’s male-dominated politics, Sevareid said what separates the men from the boys comes from the boys wanting to be something, and the men wanting to do something. I talked to the College Democrats of Ohio this week, and I didn’t use that exact quote, but I stressed that if you think about running for office, you first should figure out for yourself what you’d most want to get done in office. Would you work on stopping climate change? On dismantling structural racism? On alleviating income inequality? In any case, you should decide on what you want to do, before just deciding: “I want to be a Senator. I want to be a Congressperson. I want to be Governor.”

Hugo Black started off much more focused on being something than on doing something. Black then had the good fortune (which none of us can count on) of a lengthy political career in which he figured out how to get good things done. His politics evolved from a racist appeal, to a push for racial justice — all pretty remarkable, given his background and early record.

Voters need to decide who gets a second chance, or how many second chances you get. But this book does show that really none of these eight progressive politicians had spotless records. I don’t either. We all can look back with regret at certain decisions made along the way. For these 20th-century Senators, that especially comes up around questions of wealth, and questions of race.

What then might Theodore Francis Green’s life exemplify about the place within progressive camps for those from privilege? And when might such class traitors even prove essential in undermining the most rigged of political systems, particularly if one hopes for a “bloodless revolution”?

Right, Green, Lehman, and Robert Kennedy all came from significant wealth and privilege. But for whatever reason, Green (like Lehman, in certain respects) found himself drawing on core social-justice teachings imbued in his early life. And maybe because he emerged as a prominent political figure at a slightly later age (not because he hadn’t tried earlier — Green, like a couple other progressives in this book, lost over and over again before securing a more stable place in office), Green just always seemed comfortable and assured in his ability to stand up to interest groups.

That’s something I noticed while putting this book together. For some of these Senators, as they got more established in their position and place in life, they become even more progressive, and more willing to risk their whole career if necessary. But Green really does stand out for taking on his own coterie of friends (or at least his social class), and for thinking, at a relatively old age: Now is my time to act. He then had the good fortune to serve in the Senate for almost a quarter century, retiring at age 93.

In contrast to Black’s and Green’s long-term presence in powerful federal offices, Glen Taylor stands out as perhaps the most impactful one-term progressive of the 20th century. As an Idaho Senator with very few African American constituents, Taylor nonetheless played a crucial role catalyzing mid-20th-century calls for civil rights. As a political representative from one of the nation’s least unionized states, Taylor still stood up boldly for labor rights. How might Taylor’s politics have exemplified “a modified Christian socialism” — and even made this entertaining?

Glen Taylor was unorthodox, to put it mildly. He came out of a very hard state to win for progressives, and Republicans then retook the Senate right after his election. But Taylor showed courage by publicly rejecting the presence of the powerful, corrupt, ultra-segregationist (and Democratic, I’ll add) Mississippi Senator Theodore Bilbo. Until Taylor’s speech from the Senate floor, nobody would take on this awful, awful man. It would be like Senate Republicans finding the courage to stand up to Donald Trump today.

In terms of a modified Christianity, when I think of somebody like Glen Taylor, one of my favorite Bible passages comes to mind, Matthew 25:40, which many people today know as: “When I was hungry, you fed me. When I was thirsty, you gave me drink. When I was a stranger, you welcomed me. What you did for the least of these, you did for me.” Now, I might have a problem with this translated phrase “the least of these.” I can’t imagine Jesus really talking in this patronizing way, calling for charity instead of justice. But still, that passage from Matthew speaks directly to what Christianity means for me.

You don’t even have to call it Christian. You can call it whatever you want. But it starts from the basic principles of helping your fellow man and woman, and following Jesus’ teachings on forgiveness and decency, and combating poverty and injustice and indignity. While working on this book, I talked to Glen Taylor’s son for a good length of time, who told me how foundational that sense of justice and that sense of dignity were to how Taylor lived his whole life — when accepting the Progressive Party’s nomination for Vice President, for example, and knowing this basically meant he’d have no chance of lasting in the Senate.

So pivoting now to the Bible Belt itself, Al Gore Sr. stands out for needing to navigate paradoxical legacies of a Southern progressive populism: with the modern Southeastern economy founded on long-term federal investments, with this region still relying more than others on federal subsidies (for Big Ag, and for entitlement spending to address sustained inequalities), and yet also with the most virulent anti-government sentiments shaping its politics. And then on a more personal level, Gore Sr. must navigate the dynamics by which an especially authentic (fiddle-playing, war-time enlistee) Congressman gradually becomes a stalwart master of Senate procedure and a bold defender of progressive policies — but while losing touch with local voters along the way.

Gore, like Hugo Black, starts off wrong on race, but then gets right on race as he matures. For Gore, this ultimately costs him his seat. I mean, you never fully know in elections which decisions matter the most, but Gore just keeps gaining political strength and influence until he votes for civil rights, supports voting rights, and opposes Nixon on the war. He doesn’t come out against the Vietnam War with LBJ still in office. Though then he opposes Nixon in an important way, and also does this on a couple Supreme Court Justice nominees from the South.

Sometimes you need to choose between voting No quietly, or voting No with a volume that draws attention, that probably means you’re done. Gore felt he had to do that, and he paid the price. But I think he’d reached this kind of poised place as a political leader, where he couldn’t help saying to himself: “Why am I here? I’m here to do something, not to be something.” I admire that.

Perhaps fittingly, given the uneven pace of progressive advances, Gore Sr. and other Desk 88 figures also come across at times as not very disciplined, pulled in too many directions at once. By contrast, what makes the irrepressible William Proxmire able to harness both his showhorse and his workhorse traits like nobody else? What can progressives learn from the never terribly team-oriented (but always admirable) Proxmire’s unrivaled talents for changing public opinion and his colleagues’ votes — even on the most unwinnable-seeming issues, and even if it takes more than three thousand Senate-floor speeches to get there, as it did with ratifying the Genocide convention?

Proxmire probably cared less what people thought about him than almost any other Senator. I mean, as a class of people, we basically can’t help thinking about what other people think of us. You typically need that to get elected. But aside from his high-profile hair transplants [Laughter], Proxmire just didn’t care as much. Proxmire did what he thought was right. And even that interesting topic of his fierce commitment to the Genocide convention can’t fully capture his whole career, by a long shot. Proxmire might have fought tirelessly for certain progressive causes. Though that didn’t make him progressive on everything. Proxmire pushed consistently for his values. But that didn’t necessarily make him predictable in his political positions.

He had died before I started work on this book, but I would have just loved to talk to him. I’d consider him the most eccentric of these eight. Tom Harkin told me that when he asked Proxmire: “How can I do what you did, and win so consistently without having to raise a lot of money, and accomplish so much?” Proxmire responded: “Tom, you don’t want to live the way I’ve lived.” That always stuck with me.

Then for Robert Kennedy, could we go back to a second, less discussed but still foundational pillar of your progressive vision, alongside the dignity of work — what Leo Tolstoy describes as “the fundamental religious feeling that recognizes the equality and brotherhood of man”? Could you describe how RFK’s life trajectory leads to his distinctly “unshackled” Senate pursuits, actively pushing beyond this institution’s insular confines, so that he can engage the most marginalized Americans facing the most trying circumstances?

I don’t have a great answer. Robert Kennedy was never of the Senate. I mean, he had those three years plus a few months in the Senate. But the book gives that anecdote about Ted and Bobby Kennedy taking part in a long Education and Labor Committee hearing, waiting hours to ask their questions, with Bobby even further down the podium than Ted, because Bobby got there second. Bobby never wanted to wait. And who knew Teddy at this point still had 45 years to go in the Senate? Ted counsels patience that day, whereas Bobby operates like someone who just knows he doesn’t have very long.

Bobby only came to progressive politics in the last few years of his life. You wouldn’t have called RFK (who had worked for Joe McCarthy) a particularly compassionate figure, until his brother died. And even then, no switch immediately flipped to make him change. It took Bobby going to Bedford-Stuyvesant, going to the Indian reservations, and talking with farmworkers.

Bobby actually saw the Senate as a place where he had the duty to learn about and from his fellow Americans. So maybe he’d always had empathy, which mostly had come out around family. I don’t know. But in terms of his public career, nobody would have thought of Bobby Kennedy that way until the mid-60s. What made Bobby different in the Senate (and different from other Senators) maybe came from this thought that he had a lot of time to make up for — not that he expressed much regret or was wistful about his early career. If Bobby ultimately decided to fight for social justice, maybe he recognized that he hadn’t done this for much of his life, and now had to take advantage of whatever time he had.

If RFK embodies in that moment a compassionate progressivism, George McGovern brings back populist progressivism’s stark moral power — again prevailing for a long stretch in one of America’s most conservative states. And McGovern likewise embodies certain pivotal late-20th-century political tensions. As a celebrated war veteran and impeccably credentialed spokesperson for global diplomacy, McGovern nonetheless gets branded as “soft.” As a straight-talking idealist, McGovern inspires a whole generation of impassioned progressives to join the Democratic Party’s ranks, even as his presidential candidacy alienates other key components of the classic postwar Democratic coalition. Or while ardently engaged in electoral politics, McGovern makes his most lasting humanitarian contributions through (often bipartisan) work on domestic anti-poverty programs and global public health. So what constructive lessons can today’s progressives draw from McGovern, both as a political and a personal role model?

I actually find that the hardest question to answer here. I really can’t say why McGovern failed like he did in his presidential race, or eventually in a Senate race — other than that he faced the cheating Richard Nixon in a country that typically doesn’t vote out incumbent Presidents during times of war, and that he lost his Senate seat in a tough state and a terrible 1980 season for Democrats. But you’re asking a difficult question about George McGovern’s political skills. I mean, look at what he did to build the South Dakota Democratic Party. Look at how he eventually got the national nomination in 1972. Look at how over his life he won more elections than he lost, in such a conservative place. So I just don’t know how to measure his political skills.

I definitely consider him a good role model. I myself learned a lot about politics by working for McGovern during the 1972 primaries. And then I also displayed my stellar predictive powers by convincing most friends in college that fall that McGovern would win [Laughter]. I could list all the states that would take him to 270.

McGovern again had a lot of pain in his life. And I can’t help sensing, like you asked about Bobby Kennedy, that politicians who’ve had significant pain in their lives often make for better elected officials. My wife Connie is downstairs right now, rewatching Ken Burns’s series on the Roosevelts. I keep going in and out. Watching that, you can’t help thinking about the suffering that unexpectedly came FDR’s way, or that Joe Biden has lived through. Of course Biden has had a good life by many measurements. But imagine burying two children and your young wife. McGovern himself had some hard times for sure. I don’t have a better answer than that.

To close then, in your book’s one photo, it looks like Russ Feingold had Desk 88 for a time. He would have made it into my pantheon. But more broadly: why else do progressives need their own pantheon, of the kind this book provides? What else should they be looking for from that pantheon?

I definitely could have picked Russ. I just didn’t think I should include anybody from my own time in the Senate. I found it useful for my writing, but also just for my thinking about the Senate, to get a little more distance.

For sure.

But I do think progressives need their own pantheon. From this particular moment with COVID, with all of the economic losses, with all of the racial injustice, with Donald Trump in office, I find it especially useful to recognize that, during some of our worst national struggles (at least in the 20th century), progressive elected officials, doing progressive things, helped put us back on track, and pointed us towards a much brighter future. That’s what I see happening this year. I see the 2020 elections as all about propelling a progressive President and a progressive Senate to do big things that will benefit this whole country for decades. I hope for that. I believe in that. And I take from the examples of these eight Senators my sense of the ceaseless contributions from so many of us which can only make that possible.

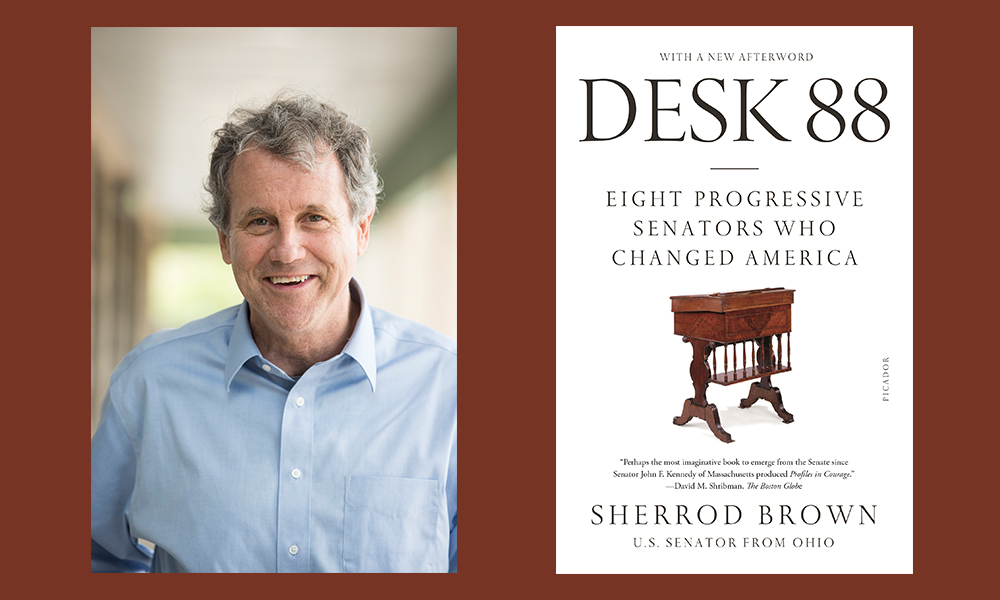

Portrait of Senator Sherrod Brown by Nannette Bedway.