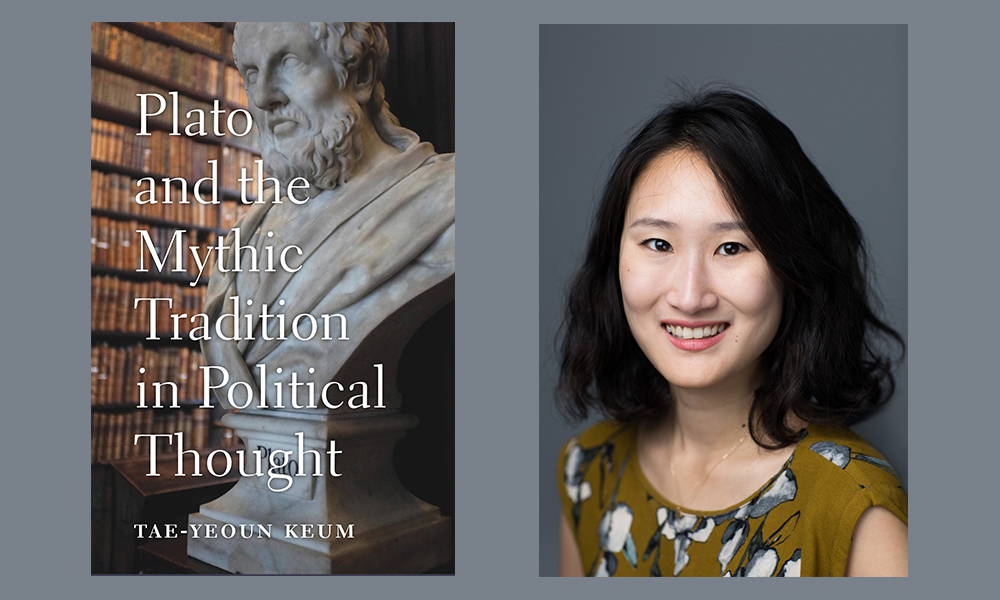

How might philosophy embrace supposedly manipulative mythmaking for liberal ends? How might philosophers use myth “to actually convey something deeper and more distinctive”? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Tae-Yeoun Keum. This present conversation focuses on Keum’s book Plato and the Mythic Tradition in Political Thought. Keum teaches political theory at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is currently working on a book about the 20th-century philosopher of myth Hans Blumenberg — within the context of contemporary European debates regarding the roles of symbols, narratives, and the imagination in politics. Our 2018 conversation about related topics can be found here.

¤

ANDY FITCH: First, in definitional terms, could you sketch how various Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment humanistic disciplines have conceived of myth?

TAE-YEOUN KEUM: Good question, and I’m not sure I can do it justice without going on too long. Myth is a spectacularly, almost disproportionately loaded concept. We start with this narrow, literary definition of myth, as a kind of traditional tale about supernatural characters and events. But sometime around the Enlightenment, intellectuals intent on distinguishing between enlightened and “unenlightened” cultures turned the focus of their critique to ancient Greco-Roman myths. They started associating myth with superstitions, unexamined beliefs, or the kind of “primitive” mentality a human being must have in order to generate and to believe silly stories about gods behaving irrationally. So that’s when myth, this fairly specific literary genre, also came to double as an ever-expanding philosophical concept representing a deeper, more elusive form of thought.

The early-20th century was another important inflection point for this expanded conception of myth. On the one hand, you had the first anthropologists compiling the myths of various indigenous cultures in South America, sub-Saharan Africa, Australasia, and the Pacific. Early anthropologists studied these myths on the assumption that they held the key to understanding a distinctly pre-modern worldview. Studies of myth from this period had just unbelievable titles, like Les fonctions mentales dans les sociétés inférieure and La mentalité primitive. Myth, for their authors, meant an entire way of thinking, distinct from how modern people thought. A simplified version of this approach might say that myth was to non-modern societies what science is for modern societies. One of the pioneering anthropologists, E.B. Tylor, certainly thought this. And an equivalent contrast enters philosophical discourse in the mid-20th century with Karl Popper, who conceived of myth as the opposite of science.

But to jump back to the early-20th century, there was also a psychoanalytic tradition that ended up pushing conceptualizations of myth in a different direction. Freud drew a parallel between the totemic belief systems of myth-rich cultures and the mind of the adolescent (as well as the neurotic patient). According to this approach, myth represented an adolescent stage in civilizational progress, just as it gave expression to the kinds of psychosexual hangups we experience as children (and are supposed to grow out of). Freud conceptualized myths as the expressed forms of forbidden desires that modern individuals secretly shared with people in tribal societies: the ancient Greeks had their Oedipus myth, and we moderns have our Oedipus complexes. The idea that mythic desires and models lurk in our unconscious minds gets a much more palatable spin by Freud’s disciple Carl Jung — and much later by neo-Jungians like Joseph Campbell, who made an influential PBS series in the 1980s that I often get asked about. But now I’ve definitely gone on for too long!

Could you also flesh out where, at present, political and philosophical inquiry might most confuse itself by treating today’s “deep myths” as the modern equivalent of ancient literary myths — as well as where contemporary examinations of deep myth and literary myth can in fact shed light on each other?

Right, in this book I try to differentiate the narrow, literary meaning of myth from this more elusive, contemporary idea of a template framework for imagining aspects of our world in a certain way. Just to give one quick example, when we use a phrase like “the myth of the artistic genius,” we’re talking about a very thick conventional framework for how society tends to imagine a figure like this: what kinds of personalities they have, what kinds of interpersonal relationships they have, even what their life stories look like. For the sake of simplicity, I’ve called such meanings “deep myths,” in contrast to the traditional genre of “literary myths.” Certain scholars of myth find this distinction artificial, and I respect that. But I think it’s still an instructive move to make, because it helps for distinguishing between a literary genre and a tremendously broad spectrum of cultural phenomena all lumped into this concept of “myth.”

This distinction helps us appreciate the historical contingency of how “myth” came to be such a conceptually bloated category. That historical sense helps us raise the exact questions you’ve just asked me: what do we gain from calling these things myths, and where does this categorization fail us?

What we gain is a way of acknowledging the narrative, symbolically fraught, and otherwise figurative elements of our own worldviews. We have these imaginative frameworks that help orient our understanding of our world and our place in it, and these frameworks might not always translate well into conventionally rational language. But this doesn’t mean that these frameworks fail to have an important influence on our thinking.

Where I think we do ourselves a disservice by conflating “literary myths” with “deep myths” goes back to this Enlightenment narrative we’ve inherited that myths are what our ancestors had (and what people in “less advanced” societies have) in their cultures. When we internalize that narrative, we are primed to be dismissive of the myth-like phenomena in contemporary culture, and to treat them as a form of thinking we should have outgrown already.

Here could you sketch a broader spectrum of contemporary perspectives on what we should do with myth — stretching, say, from an imperative dismantling of any cultural power that myth still possesses, to an embrace of myth as a vital (more or less inevitable) imaginative framework for thriving human communities? And where along such a spectrum might you find traction for qualified valuations of myth as a collective conceptual tissue resistant to certain forms of critical scrutiny, yet still conducive to modern civilizational aspirations?

The Enlightenment narrative we’ve been discussing still informs a pretty standard view of myth in the liberal tradition. This is the view that myths are irrational phenomena that we don’t want in society, that we should get rid of. One approach to eliminating myths involves simply ignoring them, either because they’re not especially serious, or because engaging them risks activating further irrationality. Another way of getting rid of myths is to take them seriously, but to try to dismantle them through facts and reasoned arguments.

By contrast, there’s an alternative, largely “continental” tradition of thinking about myths as a more or less permanent fixture of society — as phenomena here to stay, which don’t just vanish when presented with arguments. Theorists coming from this perspective don’t offer easy solutions for how to deal with myths, certainly nothing as clear cut as “Ignore them” or “Debunk them with facts.” Most basically, this approach would advise us to find ways of living with a reality in which myths infiltrate our lives and our thinking. There’s certainly much work to be done filling out the details of what this incorporation of myth might look like. But at least for me, this is the more compelling vision. On the one hand, we’ve seen a lot of discussion lately about how reasoning against myths just doesn’t seem to work. On the other hand, we also see a dizzying variety of fields focusing on the importance of narratives and storytelling. Just the other day, I found myself reading an article about “narrative medicine”! So my own position is that we should try to appreciate and to work with the unique figurative dimensions of myths.

In your book’s account, Plato’s ever-evolving intellectual reputation crystallizes this diverse range of responses to myth — with, over the past 2400 years, various readers detecting in Plato’s mythic evocations a worldview to embrace as doctrine, or a murky cultural inheritance for philosophy to overcome, or a dangerous proto-totalitarian precedent to resist. And in present-day academic contexts, Plato’s legacy might get celebrated, strangely enough, for its “methodological purification,” for “decoupling philosophy from the uncritical mode of thought particular to myths.” But could we turn to the Republic’s Myth of Metals, and consider some challenges it poses to depictions of Plato as divinely inspired, or as divorcing rational logos from pre-rational mythos, or as cynically deploying myth to naturalize existing social hierarchies? How instead might you situate this particular myth amid the Republic’s broader political vision?

Of all the myths Plato wrote, the Myth of Metals (or the “Noble Lie”) is probably the one people tend to have the greatest problem with. Karl Popper, for instance, hated this myth. He actually described it as a direct antecedent to Nazi “Blood and soil.” For Popper, the very fact that Plato appropriated the resources of myth for political purposes was in and of itself objectionable, an affront to the ideals of an open society — and, indeed, an act that seems very much in tension with this reverent portrait we have of Plato as the champion of a rationalized way of doing philosophy.

I don’t want to deny that this myth helps set up an inegalitarian political structure in the city the Republic envisions. But I also don’t consider that point the most interesting takeaway from this myth.

The Myth of Metals penetrates deep down into our conceptualization of individual nature, and then tries to write over that concept. If you read the myth closely, you find that its central task is to convince the citizens of the kallipolis that their true natures consist in traits and characteristics they’ve acquired through a basic education in music and gymnastics — the first rung of this city’s educational curriculum. That is, the myth tries to displace any notion people might have about their individual nature as an enduring set of traits predetermined at birth and carried throughout their lives. The Republic takes all this language of gestation and birth and applies it not to the moment of a citizen’s biological birth, but to the moment they have completed this preliminary phase of education.

And what’s especially fascinating about this move is that Plato repeats it two more times in the Republic. At the next juncture in the educational curriculum of the kallipolis, Socrates revisits this question of what an individual’s nature consists in, by offering the famous Allegory of the Cave. In this story, Socrates ends up once again writing over the concept of nature that he had revised just three books ago. Now we are told that the traits individuals discover about themselves through a philosophical education in dialectic were their true natures all along. And on my reading, something analogous happens in the Myth of Er as well.

My point is that the Myth of Metals has to be read as the myth that gets this whole chain going. In the broadest sense, it sets up a philosophical inquiry into the relationship between nature and education, an inquiry that Plato keeps developing across these three myths.

Pivoting then to a broader literary/philosophical/political legacy of authors engaging and emulating Plato’s mode of myth-writing, how might you see, say, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s Enlightenment-era Petite Fable “reconciling the disconcerting gap between what is theoretically intelligible and what is practically knowable”? How might Leibniz’s vivid break here from his Theodicy’s more abstruse argumentative mode help establish some bounds to an active, progressive, emancipatory human reason’s striving (itself forever imperfect, incomplete) towards perfect knowledge?

I believe the Petite Fable at the end of Leibniz’s Theodicy was modeled after the Myth of Er at the end of Plato’s Republic. Both are eschatological myths about the harmony of the cosmos, placed at the very end of a philosophical treatise on justice. Leibniz even went out of his way to give his broader treatise this fancy Hellenizing title, Theodicy (from theos and dike, the justice of God).

Like Plato’s myth, the Petite Fable is a philosophical myth carefully constructed to make a philosophical point — not just to rehash in a more rhetorically flashy way a philosophical argument that’s already been made, but to actually convey something deeper and more distinctive. In this case, Leibniz uses myth to draw our attention to a more foundational framing narrative that we must subscribe to in order to move forward with philosophy. The framing narrative is his doctrine of theodicy, that a perfectly rational God chose to create “the best of all possible worlds.” But bound up in that framing narrative is this thick, imaginatively fleshed-out mythic vision of a universe that is supposed to make sense, so that we don’t have to actively question it all the time.

Critical reason, as conceived by Leibniz and his Enlightenment contemporaries, is incredibly powerful, but can also be indiscriminately corrosive. Leibniz wanted to commit to the premise that nothing in the universe is categorically closed to human knowledge, that if we apply our critical faculties of reason with the right amount of persistence, we can, in theory, eventually figure anything out. That’s what I mean by Leibniz taking the world to be theoretically intelligible. But practically, if we let our reason loose on anything and everything all at once, that would be extremely disorienting and unsatisfying — if not actually destabilizing on an existential register. For Leibniz, there ends up being a gap between what is theoretically intelligible in the world, and what is practically knowable in it. So Leibniz needs something to frame this project of philosophy, something that tells us it’s okay to suspend our critical-reasoning faculties from time to time.

Leibniz’s particular solution to this problem is to suggest that a rational God has done our thinking for us already, so we can trust that the things we know and the things we don’t yet know all fit into a coherent whole. And the concrete vision of Leibniz’s Petite Fable allows us to appreciate where this framing narrative is coming from: why a story like this is necessary, but also how this story remains a provisional solution to an enduring problem built into the human condition.

What does engagement with Platonic mythic traditions then have to do with reconceiving German Idealism as a fulcrum for broader human flourishing, dynamically blending community-minded rational/ethical concerns with poetic/spiritual quests for personal freedom? What might it mean to see this Idealist project (at least as formulated in the “Oldest Systematic Program”) neither as an apolitical aesthetic movement, nor as some “philosophically bereft antecedent to the totalitarian politics of the Third Reich,” but as a reinvention of the Republic’s isomorphic, mutually enhancing interplay between polis and soul?

The German Idealists I look at in the book were developing the theoretical foundations for what they conceived of as “a new mythology” for the modern age. This project often gets dismissed in the ways you mention, but I consider it an extraordinary work of political theory. These German Idealists (Friedrich Schlegel, Friedrich Schelling, Hölderlin, Novalis, and the unknown author of this document called the “Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism”) diagnosed what they regarded as a pressing problem in modern politics. Developing a new mythology was their proposed solution to that problem.

Briefly, they felt that the conditions of modernity forced an unnatural dichotomy between the spiritual and creative freedom of individuals, and the kinds of political community made possible in a modern state organized around rational laws. A new mythology could help bridge this dichotomy, by offering a shared imaginative vocabulary linking together the creative pursuits of individual artists — and, in turn, a communal project that these individual artists contribute to through their work. This vision was also heavily shaped by a distinctive understanding the German Idealists had of how knowledge unfolds in history. They really did think of myth as a medium that could open up new ways of knowing, a medium that could extend the accomplishments of modern philosophy, so that it can start tapping forms of knowledge which don’t typically get captured by the toolkits of conscious reason.

As you point out, the German Idealists also had their own version of the city-soul analogy. Like Plato, they believed that one part of the soul is more responsive to reason, and one part of the soul is more responsive to poetry, and that corresponding classes of people exist in society with more developed philosophical faculties, or with stronger emotional and aesthetic drives. But the German Idealists took this analogy in a different direction. Plato’s vision of a well-ordered soul and a well-ordered city relied on hierarchical rule, with the reasoning part ruling over the other parts in a harmonious relationship. The German Idealists, by contrast, envisioned everyone having well-rounded souls, with both the philosophical and aesthetic faculties fully developed. They thought that new mythology, in particular, could help achieve this corresponding change in society, with the “rational” philosophers meeting the “sensuous” people halfway.

Finally then, how might this book’s much more textured conception of Plato’s foundational undertakings (beyond some supposedly decisive turning of one’s back on myth) point towards your concluding case that “literary experimentation with the genre of myth was more prevalent in the Western philosophical tradition than commonly recognized”? How, in turn, might this recognition unlock potential for a broadly reconceived study of the enduring prospects for constructive, visionary, inclusive (and of course ever-provisional) mythmaking — a field “that promises to be a fertile ground for better understanding an array of cultural phenomenon that often elude our attention and analysis”? And how may practitioners of this field themselves actively participate within the Platonic mythic tradition?

In different ways, the protagonists of my book were writing (or in the German Idealist case, trying to write) philosophical myths somehow modeled after Plato’s myths. They noticed that Plato used myth for philosophically constructive purposes in his writings, and they, too, experimented with the genre. The fact that they did this is more surprising in certain cases (Leibniz and Ernst Cassirer) than in others (Thomas More, some of the German Idealists). But it’s worth taking stock of the fact that there was this distinct tradition of philosophical myth-writing — in a discipline that often has been conceived as the very opposite of myth.

This might just be one particular glimpse into the formal vibrancy of philosophical writing. But appreciating this history can help us rethink some default assumptions we tend to make about philosophy, and especially about what philosophy ought to look like. We’re sometimes led to imagine philosophy as this rarefied discipline that is fundamentally about formulating and refuting arguments. But actually, that narrow image represents neither the essence of philosophy nor its history.

I’m not sure if I can say what the Platonic mythic tradition’s future will look like, though I don’t doubt that it will get taken up again for as long as Plato continues to inspire philosophers. But staying true to the broad spirit of this tradition will entail, for a start, ensuring that philosophers are open to different styles of philosophical presentation, especially from the margins of their discipline, and that they acknowledge the diverse insights we have yet to gain from unconventional forms of knowledge.

This mythic tradition should also invite philosophers (and really, all of us) to take the concerns of Plato and his successors seriously, and to pay more attention to the role that imaginative elements like metaphors, narratives, symbols, and images play in politics. When such forces take hold in seemingly irrational ways, we shouldn’t be too quick to dismiss them — nor should we just pick them apart with facts and reasons. We should instead be engaging them.