Most Buddhists I knew in the 1970s and 80s weren’t bothered when Vipassanā, or Insight meditation, was repackaged as “mindfulness” by a handful of entrepreneurial-minded physicians and spiritual teachers. You met the occasional purist who said that Vipassanā shouldn’t be offered without the ethical teachings of Buddhism to anchor it. But few actively opposed mindfulness practice. Who cared if the spiritual-but-not-religious crowd wanted to indulge in a little “meditation lite” on the side? None of us dreamed that mindfulness would become so popular, or even lucrative — much less that it would be used as a way to keep millions of us sleeping soundly through some of the worst cultural excesses in human history, all while fooling us into thinking we were awake.

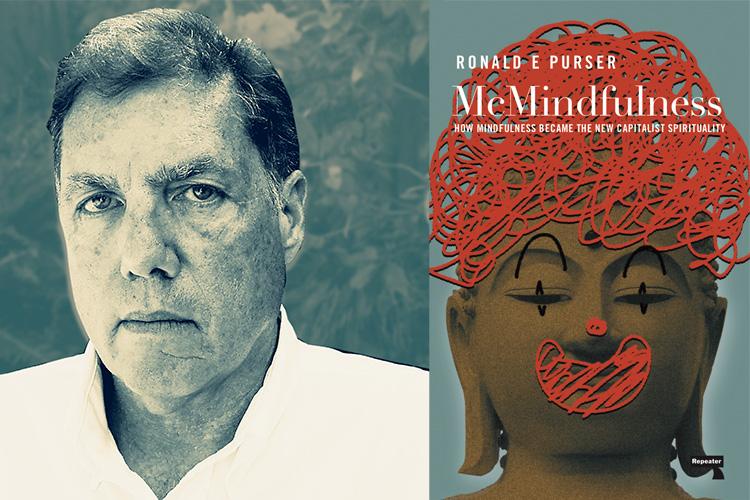

I spoke with Ronald Purser, author and co-host of the Mindful Cranks podcast, about his new book McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality (Repeater Books). As an editor for Tricycle: The Buddhist Review during the 1990s, I had been privy to some of the earliest critical thinking about the fledgling mindfulness industry. But I was unprepared for the scope and depth of Purser’s critique. The book takes a very simple idea — that mindfulness serves the interests of the status quo — and expands upon it until no stone in the seemingly pristine, serene Zen garden of the mindfulness movement is left unturned. The take-away? Mindfulness is being used in ways that its Buddhist originators never intended — for the simple reason that their philosophy wasn’t driven by the market or motivated by the desire to mask endemic suffering and social injustice.

What is mindfulness for? Does it have any ethical content? Does it produce compassionate people — or compliant people? Does it relieve stress without curing its causes? These were the questions that drove our conversation.

¤

CLARK STRAND: If stress is the symptom and mindfulness is the medicine, what is the underlying disease that afflicts so many in our culture?

RONALD PURSER: Many of us are in a deep existential despair over the state of the world. Whether you’re working in a meaningless job, or have simply gone numb as a result of so many looming crises — political tribalism, poverty, rising rates of mental illness, the ecological emergency, and perpetual wars — it is tempting to retreat inward as a means of psychic survival. But such passive resignation bespeaks of a failure of the kind of utopian vision that has always led to social change. As the late British writer and cultural theorist Mark Fisher argued, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than an end to capitalism.” Even our rage against the machine does little to effect change.

So the disease is actually despair rather than stress, as the Mindfulness Movement would have us believe?

The dominant narrative of stress is reductionistic, diagnosing the problem as one of individual maladjustment. By individualizing social problems, the practice of mindfulness disadvantages those who suffer the most under the status quo. The stress discourse also plays on public fears. Stress is an epidemic, omnipresent, inevitable. So it’s up to us to mindful up and cope. It’s seen as an individual-level problem, divorced from any historical, social and political context.

The word “despair” more accurately captures how our discontent is inseparable from our social and political worlds. However, the majority of those who have taken up the practice of mindfulness are middle-to-upper class white people who aren’t exactly despairing due to their position and privilege. They simply want a way to feel a little better about themselves while they go about their daily affairs.

On the opening page of McMindfulness, you write, “Anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary — it just helps people cope.” Is the so-called “Mindfulness Revolution” a case of false advertising?

The overblown rhetoric that mindfulness will usher in a global renaissance — that helping corporations like Google to maintain the productivity of their stressed engineers will eventually bring about world peace — this is pure marketing hyperbole. Nothing has been overturned or transformed as the result of mindfulness. And nothing will be. Mindfulness is complicit with the smooth functioning of capitalism and its institutions, and that is because mindfulness is extremely conservative. How else can we explain why it has been so warmly received by governments, corporations, and educational institutions? Mindfulness tells us the problem is our minds rather than with these institutions and how they function. So, of course, they love it.

You’ve suggested that, in the absence of any ethical teaching, a method such as mindfulness defaults to the ethics of the prevailing culture — in our case, capitalism. Is that what you were trying to get at with your pithy title, McMindfulness?

Exactly. Mindfulness as a stand-alone instrumental technique — paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally — not only absorbs our dominant cultural values and capitalist norms, but it is easily repurposed for enhancing virtually any desire, from having better sex to making a killing on Wall Street. As it is now understood, mindfulness requires no ethical or moral commitments. That explains why even the US military feels justified in training combatants in mindfulness prior to their deployment to Afghanistan.

How does an idea like that manage to worm its way so deeply into the culture and the body politic? We find mindfulness being practiced, not just in retreat centers as it was in the 1980s, but… well, almost everywhere. This is more than a self-help fad at this point, is it not?

The mindfulness movement is being led by elites. Rather than opposing institutional authorities as most revolutionary movements have done, affluent professionals have used their considerable cultural capital to gain insider access to a variety of institutions. They pitch their mindfulness programs as scientifically proven, non-threatening palliatives for maintaining social harmony, taking their place as insiders and working within existing norms, power structures and institutional goals.

Like many other social science interventions, which draw their legitimacy from the authority of scientific language and professional expertise, mindfulness offers interventions that make productive use of human resources — in this case, enhancing the mental fitness of its subjects. In a word, mindfulness makes its practitioners more self-governable.

How would you describe Neoliberalism and what does it have to do with the practice of mindfulness? Are the two joined at the hip, or is it just an unhappy coincidence that mindfulness, like a weathervane, should find itself pointing in the direction of the prevailing cultural wind?

Neoliberalism is a perverted notion of freedom that is supposed to arise spontaneously by cutting away anything in society that impedes pure market logic and interferes with individual competition. It’s a socio-political ideology that views individuals as entrepreneurs running their own private, personal enterprise — the business of Me, Inc.

The ideological linchpin of neoliberalism is the privatization of social responsibility. One constantly hears the trope among mindfulness teachers that the only real change comes from within. The burden of change is placed squarely on the individual to adjust to external conditions. As Jon Kabat-Zinn is fond of quipping, “You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.” That’s neoliberal philosophy in a nutshell. Go with the flow, and not against it.

Just as there are people out there who believe that Marianne Williamson wrote A Course in Miracles, the spiritual text she has drawn her principal inspiration from, there are surely some who believe Jon Kabat-Zinn invented mindfulness. Could you tell us where mindfulness came from?

That’s a long and complex story. Mindfulness appears in Buddhist texts as early as the first century BCE. But even within Buddhism, mindfulness has been subject to varied understandings and applications, depending on the time period and context. What we see now is a highly psychologized version of mindfulness, adapted from meditation techniques that were themselves the outgrowth of lay meditation practices developed in Burma under British colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Since then, there has been an ongoing process of modernization that cleansed mindfulness of its Buddhist roots, refashioning the practice into a privatized spirituality that addresses the problems of modern living. The mindfulness movement is Buddhist meditation twice removed.

What is the difference, then, between Buddhist mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Kabat-Zinn’s carefully branded version of the same.

As originally practiced in Buddhism, the purpose of insight meditation was a radical transformation of the self — an inner revolution in one’s vision of reality coupled with a spontaneous moral engagement with the world. By contrast, contemporary mindfulness-based interventions are essentially therapeutic, with an overall focus on reduction of psychosomatic symptoms — stress, anxiety, chronic pain, etc. Mindfulness practices are also utilized to connect individuals with their immediate sensory, present-moment experience. Think of the mindful, be-here-now exercise that has become part of so many mindfulness training programs — the extremely slow and prolonged eating of a single raisin.

You sometimes revert to the language of religion in order to demonstrate that, far from being the new-and-improved spiritual method it purports to be, mindfulness is in many ways the same “Old Time Religion” that Americans are used to. You speak of “priests of mindfulness,” “mindfulness missionaries,” and “self-monitoring” of mental states that is strangely reminiscent of Protestant examination of conscience. Do these just go with the territory, or are they a part of the Americanization of mindfulness?

Mindfulness is strongly influenced by American Transcendentalism. Kabat-Zinn’s books wax poetic about the beauty of the present moment, often drawing inspiration from Thoreau, Emerson, and Whitman. As a treatment modality, mindfulness also hearkens back to the New Thought movements of the early 20th century, whose evangelists hawked meditation as a practice for spiritual healing.

Today mindfulness serves as an update of the Protestant work ethic. We are taught to be self-vigilant, constantly monitoring our conduct and regulating our emotions as good neoliberal corporate subjects who can dutifully accept the status quo. The “mindfulness work ethic” serves as a salve for tolerating oppressive or toxic workplaces, promising a means to career success as we learn to adjust and harmonize with the demands of the corporation.

Mindfulness is being sold by its promoters as the cure for a wide variety of emotional ills and psychological maladjustments, but in your book you seem to be suggesting that it may be making us worse. Could mindfulness be making us sick?

Because it focuses so much on making “me” feel better, mindfulness can lead to narcissistic self-absorption. Because it is marketed as a tool for enhancing personal success, it can also foster an obsession with personal advancement. As recent studies have shown, the benefits of mindfulness meditation are much more modest than its proponents have claimed. A John Hopkins University study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found “no evidence that meditation programs were better than any active treatment (i.e., drugs, exercise, and other behavioral therapies).”

An advertising executive told me recently that one of his clients, a vitamin company, was preparing to meet “the wellness backlash,” which he described as a growing resentment among consumers at the idea of having to constantly monitor every aspect of their health. Is your book a part of that backlash? How much of McMindfulness is driven by resistance to that trend toward obsessive self-preoccupation? Is it personal for you at all?

Mindfulness is a significant chunk of the $4 trillion wellness industry, and just like the obsessive self-surveillance associated with diet and exercise fads, “being mindful” has become another burdensome cultural moral imperative. It’s a continuation of the neoliberal trend called “healthism,” whereby individuals are expected to take sole responsibility for their own physical and mental well-being.

As a technology of the self, mindfulness works subjectively, instilling an entrepreneurial sense of the self as a project that must constantly be improved, enhanced, and optimized. This calculated management of life has been a quest among utilitarian thinkers dating back to Jeremy Bentham. Mindfulness functions as an auto-exploitive tool — a panopticon for the mind. An acceptable bandwidth of neoliberal affects and behaviors (termed “emotional intelligence” by Daniel Goleman) are engendered by mindfulness practice. Calm, agreeable, accommodating, accepting, orderly, and never unruly or angry — this is the portrait of the successful mindfulness practitioner.

Why did those Americans who developed mindfulness practice in the 1980s and 90s want to distance themselves from Buddhism? Buddhism was gaining popularity in America during those years. Why not capitalize on that?

Buddhist meditation was still associated the counterculture at that time — and, of course, with Asian religion. Kabat-Zinn was a white guy with a PhD in molecular biology from MIT who believed that mindfulness needed to shed its religious affiliations to Buddhism in order to gain traction in the culture at large. Removed from its religious context, mindfulness could be imported into secular institutions like state hospitals, public schools, corporations, and government agencies. It could also garner federal funding for scientific research from the NIH.

Was the “American big-bang myth” of the creation of mindfulness by Kabat-Zinn et al. just a case of “rebranding” the wheel, or did they make significant changes to mindfulness as it was practiced by Asian Buddhists monks?

Although Kabat-Zinn milked Buddhism for its exotic cultural cachet when promoting mindfulness to the market culture, the Americanized mindfulness he promulgated ultimately became a form of “meditation without the Buddhism.” He advanced a doctrine of “universal dharma” that transcends cultural contexts and provides its adherents an unmediated access to “pure awareness.” It seems that Americans have a peculiar naïve blindness when it comes to believing they can have unrestricted private access to enlightenment. Kabat-Zinn distanced himself from Buddhism, becoming a self-proclaimed guru in the great American tradition of valorizing personal experience as the primary source of truth and authority.

You speak of the “stripped-down and decontextualized model of mindfulness” as problematic. What do you see as the problem with extracting something useful from its religious context so that it becomes available to a much wider range of people, many of whom have no interest in religion or even spirituality?

My criticism is not with people who are receiving therapeutic benefits from mindfulness, but with its reproducing the structures and norms of capitalism. Stripping mindfulness from its ethical teachings on morality, along with the Buddhist teachings on wisdom, allows it to be deployed as an attention enhancement tool for virtually any purpose. Seen as a DIY self-help technique, mindfulness falls neatly within the bounds of therapeutic culture that naturalizes stress, individualizes social and political problems, encourages accommodation to the status quo, and gives Wall Street traders an extra mental edge.

Part of your critique of mindfulness centers on what you call the “de-narrativization” of individual experience. You cited Kabat-Zinn’s description of mindfulness a “body-centered field of awareness that doesn’t have to have a narrative or doesn’t have to believe in its own narrative or take it seriously.” I couldn’t help but think of the extraordinary narratives that have come out of #MeToo movement and the efforts by powerful men to silence them. Where does mindfulness stand on speaking up and speaking out?

I recently spoke with a Dutch journalist who told me that she took an eight-week MBSR course and that she saw strong parallels with the backlash against speaking up in the #MeToo movement. During the course, she attempted to share her concerns about how unrealistic workloads and other matters in her workplace were causing her so much stress. The mindfulness teacher cut her off, telling her that these sorts of narratives were not appropriate to dwell on. The teacher instructed her to pay more attention to her first-person subjective experience of doing the mindfulness practice, essentially silencing her.

This is a perfect example of how clinical mindfulness practices privatize stress, locating the causes for psychological distress within the individual. The clinical and therapeutic orientation of mindfulness courses is limited to bio-physiological narratives that avoid any sort of social, cultural, or political analysis. It’s hard to take a stand and speak up when mindfulness teachers tell participants that the practice will help them “to accept and see things as they are.”

A recent NIH peer review described the effects of mindfulness on the brain as “trivial.” If that is true, that’s a lot of wasted money on the part of corporations like Google and Facebook, not to mention the U.S. military. What’s driving the perceived cost-benefit gains of such big players if not changes to the brain?

This isn’t the first time. In the 1990s, the NIH poured $23 million into research on Transcendental Meditation that was eventually discredited. But there are deeper reasons. The history of business management has been a quest to mold employees to suit the interests and needs of capital. Industrial psychologists, management consultants, and corporate trainers have colluded with corporations going back to Frederick Winslow Taylor and his so-called “Scientific Management.”

Despite the lack of solid science, corporate fads have a way of gaining traction — in part because of their promise to enhance profitability and performance. Companies like Google also adopt mindfulness programs as form of virtue signaling — a way of saying, “Look how much we care about our employees’ mental health and wellbeing! In reality, corporate mindfulness is just the latest technique for training employees better to serve their employers.

But let’s be clear about what mindfulness is not. It is not an industrial form of brainwashing. What it does is deflect attention from collective organizing, or the pursuit of structural changes in corporate culture. Instead it refocuses employees on productive self-discipline. It works like a sophisticated form of bio-power, binding people’s inner lives to corporate success.

Given that the profit motive that drives most modern economies can and will corrupt anything, is it mindfulness or capitalism that is ultimately to blame?

Both. Mindfulness programs have become complicit with a neoliberal agenda.

You mentioned those trendy little mindfulness apps in your book. I mean, how could you not? Are such products a sign of the spiritual end times, or do they have any legitimate use?

Such apps are the epitome of McMindfulness. Like fast-food meals, mindfulness apps are convenient, accessible, cheap, and offer a quick-fix, low dosage burst of serenity — just enough to put a band-aid on everyday anxieties. For that very reason they are a big part of the problem.

Apps gamify mindfulness, turning it into a competitive sport (“See how many other people are meditating right now!”) and vanity project (“Look, I am sharing how many times I used the app with my social network!”). Mindfulness apps are a perfect example of the McDonaldization of mindfulness — mass producing a technique that is an efficient, scalable, quantifiable market commodity.

I never expected Jon Kabat-Zinn to be anything but what he is — an expert brander in the great American tradition spiritual entrepreneurship. But I get the feeling that you wanted him to be more than that. Did you have hopes for the mindfulness movement that haven’t been fulfilled?

Kabat-Zinn has a big platform, and it’s a shame that he fell prey to the typical New Age guru syndrome. But that’s nothing new. Capitalism has coopted Asian spiritualities going back to the late 19th century as a way to encourage quietism and accommodation to the status quo. The commodification of mindfulness virtually ensured that it would be politically conservative. Kabat-Zinn simply capitalized on middle-to-upper class aches and anxieties. People wanted to feel a little better — just 10% Happier, as Dan Harris’ book by that title suggests — and mindfulness offered that palliative.

To what extent is mindfulness a broad-spectrum self-treatment program for climate anxiety? Is climate catastrophe being directly addressed in mindfulness settings — or is it just another fear to “catch and release” on the meditation cushion?

Currently, the mindfulness movement makes no real demands on its followers. Despite all the evangelical rhetoric, it displays a remarkable conservativism and is led primarily by elite, upper class white men. For that very reason, the mindfulness movement has been politically disengaged.

The Greeks referred to those who did not participate in public life as idiots, taken from the Greek term idios, meaning “a private person” or “one’s own.” What we need now is a “civic mindfulness” that goes beyond stress reduction, self-management, or simple self-care. A responsible, civic approach to mindfulness might offer a prophetic critique of capitalism, fostering a more socially-engaged commitment to respond politically to the climate crisis.

But you yourself see no evidence of the mindfulness movement trending in that more socially responsible direction. Where does that leave us at this moment as a species, do you think?

As a species, we’re lost and suffering a crisis of meaning. Our capacities for knowing are restricted to very narrow settings, motivated by self-interest, protectionism, greed, and a perpetual recycling of our insatiable desires and cravings. Ironically, these are the very issues that Buddha addressed and which his disciples sought a cure for in mindfulness practice. But that isn’t the way mindfulness is being practiced in the West today. We are only adding to the problem.