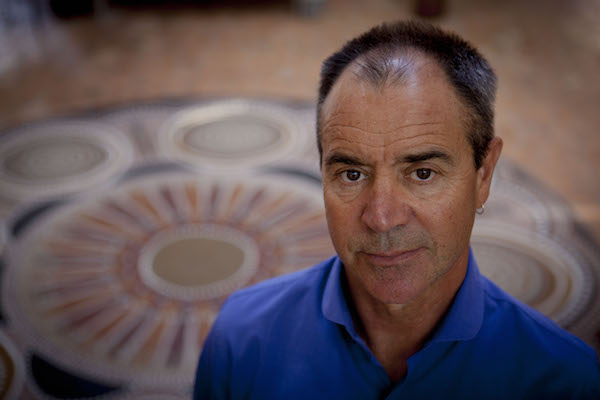

Australian writer Kim Scott’s novels include True Country, Benang and That Deadman Dance. He was the first Indigenous person to win the prestigious Miles Franklin Award and is highly regarded as a member of the Noongar community working towards language maintenance and renewal. He was trained as a teacher and worked in the northern part of Western Australia before settling in Fremantle. He was the West Australian of the Year in 2012 and is currently a Professor at Curtin University. Our conversation focused on his new work, Taboo, which was released in July 2017. It is a novel about settlement, colonization, family, trauma, history, and language, and features a cast of characters in a regional setting. We spoke about the importance of elders, the intimacy of reading, and our relationships with history, imagination, and writing.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: How did you come to writing? What did you read growing up?

KIM SCOTT: I read everything and anything. Comics, labels, street signs. Number plates. I remember being very taken with the letters on the back of my father’s overalls: MRD. It stood for Main Roads Department. The first novel I remember reading was Tom Sawyer. It was sent to me by my grandfather who was estranged from my father. My father’s name was Tom. Tom Sawyer starts off with, “Tom! Where is that boy? Tom! Where is that boy? Tom! Where is that bloody boy,” or something. And I think that’s what got me into reading at such a young age (I was seven). I thought the novel was about my dad, which provided a powerful motivation; I thought there was some kind of secret contract between his father and me — I’d get all dad’s secrets from when he was a kid.

I studied literature at university. I went to do marine biology, as I recall, but I was too shy, not prepared properly for labs and the real science of it. The other students seemed to know what they were doing. I didn’t. Wasn’t up to it. I think I may have ended up doing literature because I could hide away, really. I always loved falling into books and stories. And when I became a teacher of English, the serious attempt at writing began. Because I felt a bit of a fraud as an English teacher. You know, the Manual Arts teacher could build a house and fix his car. In Home Economics the teachers could cook. And I was meant to teach kids to write. How? By looking at textbooks? So I thought I should try and do it. And so it went.

Your novels are often described by critics and readers as having some magical realist qualities. Can you talk about the presence of the supernatural or the fantastic or the mythic in your work?

There is a bit of genre hopping in the new one, Taboo. Fairytale, there’s a bit of gothic maybe, a bit of zombie too, and so on. That is conscious — those resonances. The critter in Taboo I inherited from an earlier, failed, book. And I just really wanted that sort of being to become plausible and real. Is that Magical Realism?

I don’t know about Magical Realism really. I do remember being struck by Peter Carey’s The Fat Man in History, that collection of short stories. The audacity and energy of it. I hadn’t encountered anything like that before in Australian writing. Not that I had any sort of overview. Of course, I’d read Marquez. With Benang, which I think some have referenced as Magic Realism, well…It was a reaction against the linear logic, the cold and arrogant matter-of-factness and complacency, the racism…all those things in A. O. Neville’s [Protector of Aborigines] book, Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community.

It was how I dealt with it, the only way I could write in response. Neville speaks of the need to “Uplift and elevate a despised people.” So I uplifted my protagonist alright. Had him floating around. Trapped in the corner between ceiling and wall. It wasn’t, “Oh, I’m going to do Magical Realism.” It was just a reaction to what I was encountering in the archives and local history manuscripts: the oppressive policies, the bullshit and cruel condescension, the cool racism. Mad. Frustrating. And it seemed there was nothing at hand.

Can you speak of that frustration in relationship to history and Aboriginal identity?

My second novel Benang came from a desire to not be condescended to as an Aboriginal writer and take on these so-called masters of language in their own terms, the historians and bureaucrats-as-scribes. And then some sort of success with my first novel, True Country, meant I had to ask: where are the Noongars in my audience? Who am I writing for? So the last pages of Benang are perhaps a metaphor for literary work, of a kind; a fella making the sounds of country — a metaphor for Indigenous language — gathering a community together, which was just, you know, me wishing, at that stage. And what I thought was the need, rather than reactive polemic, and the solution to our dilemma, as a First People.

That wish has become more of a reality now hasn’t it? Through your engagement with community members as a writer, and in a language-sharing capacity?

In a way, yes. I handed a lot of books out down along the coast to people. One woman rang before I got back and left a message: “You’ve given a voice to our pain,” which was lovely, I think. So she was one of the few that read it. Mostly, it was like a novel is a cultural artefact moving in that “other world.” I wasn’t reaching into my own people. I remember one fella saying, “Oh, I got that book of yours yesterday, Kim. I got about 50 pages, and I thought, fuck. I’ll give that away.” Literacy levels, I guess. And literary ways of reading.

A novel doesn’t provide the infrastructure for transmission or consolidation of endangered heritage, not to most of us. Nor of our beautiful, endangered ancestral language, that elders like Hazel Brown carry. My work with community language groups is a way of being a “literary man” in a community context. Not just posturing. And the so-called high literary stuff or whatever it is, is both very private and a reaching to “friends, many of whom I don’t yet know,” or however Galeano puts it. Speaking to a wider circle, an imagined community out there.

It’s like a split focus, but motivation is very similar. The Noongar language and community work — working with love, in a way — matters. Reuniting language and old stories — Creation stories — with landscape, as part of a community of survivors, being a catalyst for this recovery and spirit…It has an authenticity, a groundedness. That’s the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Story Project.There’s historical massacre at the heart of our ancestral country, a “depopulation” and devastation, and we return with story and song and its sounds.

And I thought if I can do these two things, if I can have literary success and use it to shine a light on that other community work to try and keep it going, you know, that would be a good way to try and operate. The community engagement helps to see stuff in the archives that I’d otherwise miss, too.

That partly brings me to this question of audience. Who do you write for?

I write for me, but — I hope — without being self-indulgent. You know? This is for me as someone who reads, who likes to savor texts. I like when you’re reading something and you can feel the rhythms of it vary; it pulls you up. And you have to savor it, and you’re dwelling in it. And then the rhythm, it changes. Savoring language. I like that sort of thing. Not so much allusions and cultural references in a literary way because I’m not erudite enough for those. An imagined audience. An audience yet-to-be.

I think part of writing for yourself is that you’re also writing to keep company with your younger self and your older self. So it’s like you’re still writing for the boy who is hearing the words “Tom.”

Yes. Well that’s part of the magic and the intimacy of it. I increasingly think of novels as such an intimate form. One on one, for hours at a time. Reader and writer, creating a sensibility together. So, yeah, you don’t want to be too cheap about that experience. But I don’t want to bog them down unnecessarily. That’s why I like the idea of layers. And it needs a certain kind of reader.

The community project — the language and story “recovery” gives us something different from a lot of current political culture discourses, the polemic. The politics is there, of course. But these old stories can bring power, they’re an important part of identity and belonging. And sharing them, making them part of a just exchange, moves us to the centers, not to the margin. And they can nourish us, just in themselves. It’s absolutely fundamental for national identity. Healing, without relinquishing power. The anchoring of a shimmering nation state to its continent — through languages and all these different cultural traditions. A transformation.

David Unaipon has a great quote in trying to promote an Australian literature that was reconciled to the myths and stories of the continent itself and to create literature from that.

Absolutely. They are good stories and they resonate. And they stick with you and they linger, and you have to stay with them, and you get more and more out of them. There are stories like that in this ancient stuff we work with. It’s also literary in a way, the risk and vulnerability and intimacy that are part of our workshops. And trying to put words to it. Which I’m not doing well just now, I realize.

That means maintaining and protecting the past, which we have to continue to do. Can you tell us what does the future hold for you? Do you have some carcasses of novels that might come to life again?

Yeah. I’ve got some ideas. Embryos, rather than carcasses? One of the things I’m working on at the moment is with Blackfella Films, with Rachel Perkins. An historical drama TV series, 1788-1792. Fantastic material. I’ve really enjoyed it so far. Who knows how far we’ll get with it. There’s only four episodes planned. I’ve done a first draft of three of them. It’s wonderful to have someone like Rachel responding to what you’re doing and suggesting stuff, particularly in the appropriately complex political nitty gritty. Talking that through, playing with it, it’s a privilege.

In terms of the community language group, we’re extending on the Wirlomin stuff with song with the same sort of process. We’ve got a number of songs recorded already plus archival stuff, the same process as we use with the stories. I’d like to get people — people connected to the composers and the singers in the archives — singing them. Make ourselves instruments for the spirit that moves in those old songs of place.

Header image by Janine Boreland