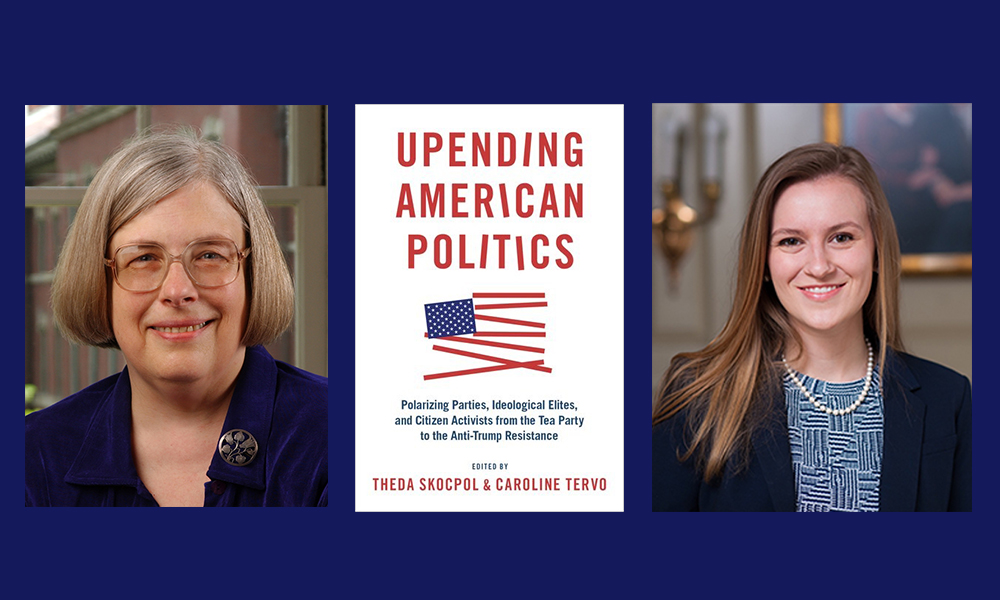

What can the Koch network’s electoral and policy successes from the past two decades teach us all about effective 21st-century political organizing? What have post-2016 Democrats done just as effectively, and without the corrosive political polarization? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Theda Skocpol and Caroline Tervo. This present conversation focuses on Skocpol and Tervo’s edited collection Upending American Politics: Polarizing Parties, Ideological Elites, and Citizen Activists from the Tea Party to the Anti-Trump Resistance. Skocpol is the Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University, Director of the Scholars Strategy Network, and past president of the American Political Science Association. Tervo is a research coordinator in the Harvard Government Department, focusing on citizen grassroots organizing, state and local party building, and the localized effects of federal policy changes.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Given America’s federalized structure of governance, given the electorate’s present divides along interlocking demographic lines (of class, region, age, race, gender), given the 21st-century American right’s effective coordination (with comparable post-2016 prospects on the American left) of widely dispersed political energies (among activists, civic organizations, donors, special-interest groups, think tanks, media outlets, public officials), could we first address Upending American Politics’ emphasis on tracking and assessing how today’s “separately organized actors…build off one another’s actions and together bring about major political shifts”?

THEDA SKOCPOL AND CAROLINE TERVO: Thanks for your question. Upending American Politics came together quickly last spring, when we realized that results from several of the projects we are doing with research associates add up to a coherent story of contemporary American politics. Although each chapter is authored by a different researcher or team, the book offers an overarching interpretation, because all of us share findings and use similar methods — focused on the organizations (and coalitions of organizations) that empower groups on the right and left in today’s fierce political battles.

For the nation as a whole and for swing states like Wisconsin and North Carolina, we explain how the Koch political network has pushed the Republican Party to the far right, and we untangle the Christian conservative, pro-gun, and police networks that boosted Donald Trump’s popular support in 2016. Key chapters also explore the Tea Party movement that reacted to Barack Obama’s presidency starting in 2009, and the resistance movement that pushed back against Donald Trump’s presidency starting in late 2016. For both of those movements, Upending American Politics offers unique information about thousands of local volunteer citizens’ groups that led the charge to “save America” from the threats they saw in a new president backed by his own political party in Congress.

New types of evidence marshaled in this volume explore organizational formations among wealthy donors, professional advocates, and grassroots citizen activists. Some authors use internal documents unintentionally leaked from meetings of wealthy donors. Others have mined Internet sources to uncover the innerworkings of 2018 election campaigns, to document the activities of national advocacy organizations, and identify local Tea Parties and grassroots anti-Trump resistance groups that have reshaped politics across entire states like Pennsylvania and North Carolina. Contributors to Upending American Politics have also traveled far from their university bubbles to make field visits and conduct vivid personal interviews with local activists and political leaders. The results offer intimate and often dramatic insights into the people and organizations driving changes around today’s clashing Republican and Democratic Parties.

To flesh out how coordination happens on today’s American right, could we pick up the premise that, before 2016 gave us the triumph of Trumpian populism, elite conservative organizing already had coalesced to advance a free-market libertarianism? Could we outline a dynamic confluence of features fueling the Koch network, with its centrally coordinated yet widely distributed institutional reach, its combined focus on electoral campaigns and long-term policy goals, its simultaneous cultivation of far-right ideologies and integration into Republican Party operations (again at all levels of governance)? From one perspective, this Koch network remains fundamentally at odds with a genuine grassroots populism. From another perspective, this Koch network has masterfully honed a catalyzed coalition to implement its ambitious legislative, regulatory, and judicial agenda. How should progressives hoping for sustained coalition-building on the left think about this conservative network’s ongoing strengths and vulnerabilities?

Theda’s first chapter of Upending American Politics tracks “The Elite and Popular Roots of Contemporary Republican Extremism,” and makes the case that the Trump presidency represents an uneasy synthesis of two separate extremist forces that have buffeted and remade the Republican Party: elite-driven, ultra free-market conservatism, combined with racially anxious popular ethnonationalism.

During the 2000s, far-right elite donors and political organizations they fueled took resources and control away from established Republican Party leaders. Tightly coordinated non-party organizations (led by Charles and David Koch) led the way in pushing GOP candidates and officeholders to advance big tax cuts tilted toward the very rich, to weaken labor union rights, and to eviscerate government regulations affecting businesses and environmental conditions. The Koch brothers went far beyond individual contributions — constructing a big-donor club with some 400 to 500 conservative-minded billionaires and multi-millionaires willing to bankroll ongoing organizations to create new ideas, advance anti-government policies, and fund both elections and grassroots policy campaigns. At the heart of this Koch network is Americans for Prosperity, a unique, massive, federated advocacy network controlled by a corporate headquarters in Virginia, with paid employees and conservative volunteers operating in most states around the country.

Professionally driven ultra free-market efforts such as those propelled by the Koch network have not been the whole story, however. From 2009 on, a wave of popular conservative organizing unfolded at the grassroots of the so-called Tea Party that fiercely pushed back against President Barack Obama and Democrats in Congress. More than a thousand local Tea Party groups formed all over the country, led by older white men and women who mouthed support for many free-market goals favored by elites on the right, but who also gave passionate voice to popular anger about too much immigration and changing family morality. Popular ethnonationalists, as we call the grassroots Tea Parties and most fervent Donald Trump supporters, are pushing back against recent ethnic, racial, religious, and generational changes in American culture and politics. Popular passions on the right are not exactly the same as elite priorities — even though both sides have come together to defeat Democrats and liberals, and make the most of the Washington power monopoly gained by the Republican Party in January 2017, when President Trump and a conservative GOP Congress took office at the same time.

In the Trump era, these two prongs of Republican radicalism have come together. By the time Donald Trump descended his golden escalator, espousing anti-immigrant sentiment, rank and file Republicans had little faith in conventional party leaders who they felt had not done enough to stop illegal immigration or same-sex marriage. Donald Trump was certainly not the top pick of Koch network leaders and Republican Party honchos, but he ran away with the nomination, buoyed by support from core loyalists sympathetic to views earlier held by Tea Partiers. Once in office, President Trump looked for ways to combine big-donor and popular support. He has embraced Koch network priorities, hiring its staff for key administration posts and enacting upward-tilted tax cuts and rollbacks of environmental protections. Separately, President Trump has thrilled ethnonationalist populists by installing officials who pursue anti-immigrant crackdowns and remove fetters on police behavior toward minorities.

Then in terms of how localized organizational networks can prompt rapid electoral and/or ideological pivots, and can sustain transformative policy agendas, could we look at what your book describes as the “unremitting rightward movement” in North Carolina over the past decade? Here could we address what historically would have been an atypical phenomenon in American politics, with one major party not only gaining significant new electoral momentum, but pushing an increasingly extreme platform at the same time — increasingly unpopular even among many of its own moderates? How, for instance, have disciplined conservative networks succeeded at resisting the desires of both Republican and Democratic governors, both healthcare and business leaders (and, of course, a significant portion of the electorate), when it comes to Medicaid expansion?

Yes, it is unusual. Traditional political science models indicate that parties gain power by leaning towards the middle, enacting and supporting policies that are favored broadly by most constituents. But Republican lawmakers both in Washington and in many states have defied that expectation, and instead have pivoted sharply to the right in recent years. Upending American Politics looks in particular at North Carolina, where even veteran lawmakers who historically voted with Democrats to pass compromise legislation have signed on to measures unpopular with some Republicans, business leaders, and voters at large: such as new restrictions on ballot access, and refusals to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid eligibility to citizens just above the poverty line.

To understand this rightward shift in North Carolina, Caroline’s first chapter in this book considers the impact of new connections between state government and conservative organizations to the right of the Republican Party. Professionally run think tanks and advocacy organizations, established in just the past two decades, have built and crystallized trusting relationships with elected Republicans. Among these are Americans for Prosperity-North Carolina (one of the earliest state operations founded by the Koch network’s federated behemoth), and policy watchdogs like the Locke Foundation and the Civitas Institute. These organizations work together to provide policy proposals, training, research, and other resources to legislators and candidates. They also pressure lawmakers to enact ultra conservative policy agendas and to refuse compromise on Democrat-supported legislation.

At the same time that elite networks built new connections with state lawmakers, an especially robust burst of popular Tea Party energy hit North Carolina. Active local groups organized across widespread political geographies, coordinated with gun-rights and Christian evangelical networks, and effectively mobilized conservative voters during elections. In turn, professional advocates headquartered in Raleigh welcomed this energy, working to translate it into state-level electoral and public policy gains. The North Carolina Americans for Prosperity operation in particular had unusually close ties with individual Tea Parties, above and beyond loose coordination seen in other places. New relationships between elite and grassroots conservatives have boosted state Republican electoral prospects, at the same time that they have pulled policy outcomes further to the right.

Although disagreements over varying popular and elite priorities remain, new connections between conservative networks and state lawmakers have shaped possibilities for governance in the state. For example, conservative networks have thwarted attempts by Republicans and Democrats alike to expand Medicaid eligibility. Governors from both parties tried to push state legislators to support this policy, but elite conservative organizations have mobilized activists in legislators’ districts, and churned out a trove of anti-expansion research papers and opinion letters. Enough powerful lawmakers are unwilling to negotiate on any form of Medicaid expansion that the policy has been blocked successfully thus far. The COVID-19 outbreak will likely exacerbate these tensions, because without Medicaid expansion North Carolina citizens will have fewer coverage options as they lose their jobs and incomes, and more families may experience a gap in insurance coverage.

To pivot back now to a national level, Upending American Politics also notes that, compared to Tea Party mobilizations, anti-Trump mobilizations have been even less top-down, even more widely diffused across America’s geographical and cultural landscape. Yet your book argues that, at least so far, the ways that progressives, liberals, and moderates have complemented each other and coordinated together has not pulled the Democratic Party to equivalent ideological extremes. So to what extent do you see today’s expansive anti-Trump constituency arising in response to Trump himself being such an alarming figure? To what extent do you see this emergent coalition figuring out new and effective strategies for working across certain demographic, ideological, and sensibility divides? And how might this coalition’s distinctive breadth (so crucial to 2018 electoral outcomes) give it better or worse traction in formulating a longer-term policy vision?

After the 2016 election, many Americans on the center-left reacted with horror and fear, and started organizing volunteer groups in cities, suburbs, and towns all across the United States — with the largest concentrations of groups appearing in swing states and districts. This widespread popular reaction to the incoming Trump administration (and co-partisan Republican majorities in Congress) was the flip side of mobilization on the right just eight years prior, when Barack Obama and a Democratic Congress were elected. Anti-Trump activists met in December 2016 through the Pantsuit Nation Facebook group, or in January 2017 while traveling to Women’s Marches in Washington or hundreds of regional cities where “sister marches” happened.

Small groups of leaders, mostly college-educated white women, decided to form groups in their home communities, and dozens to hundreds of people turned out at founding meetings and subsequent gatherings during 2017 and 2018. Members of our research team have studied both the Tea Party movement and the new anti-Trump resistance movement, and we find that current volunteer citizen resistance against the Trump-led GOP is actually more widespread, and involves more local groups and regular participants (though the Tea Party was very large and widespread itself). Both movements have created voluntary organizations spread all across the US political geography, in communities big and small. A crucial finding developed in our book is that this new liberal citizen’s movement is happening everywhere — not just in blue coastal states, or liberal enclaves like cities and college towns in the heartland. Furthermore, we show that middle-class white Americans are the most prominent participants in both the grassroots Tea Party and the grassroots resistance. Men and women have been involved in both, but white, college-educated women are the overwhelming majority of leaders and participants in current resistance groups.

Many chapters in our book let grassroots actors speak for themselves, to give a vivid sense of why they have stepped up their political engagement. In our interviews and questionnaires, for example, grassroots anti-Trump resisters speak passionately about their distaste for the president. Yet many also explain that they want to save the country as an inclusive and forward-looking democracy, and hope to revitalize democratic engagement. Like Tea Partiers a decade ago, resisters also enjoy working with like-minded others to improve their local communities.

Our research shows that, after resisting Republican attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act through the summer of 2017, most resistance groups pivoted quickly to efforts aimed at supporting Democrats in 2017 special elections and the November 2018 election. Many resistance activists themselves ran for local, state, and Congressional offices. Volunteers from thousands of these groups brought new energy to tried and true actions like canvassing door to door, registering voters, and turning them out. Group members got involved early with local Democratic campaigns, and in many instances may have made the difference in securing tight victories.

As key chapters in Upending American Politics explain, our researchers have looked closely at evolving relationships between volunteer resistance groups and local and state Democratic Party organizations. Most groups got going outside of official party auspices, and have maintained their independence either because members want to push the party from the left, or because groups want to make room for moderates and independents. But even though resistance groups affiliated with the national Indivisible network (or with other national or regional networks) stay formally outside the Democratic Party, their members often work closely with party officials and even run for party offices. Sometimes cooperation is tense. Sometimes it is warm and close. But either way, local resistance groups are gradually reforming and revitalizing the grassroots of Democratic Party politics — a process we document in detail across the entire state of Pennsylvania, and in particular communities in other states.

This marks a real change for the Democratic Party, which had allowed its grassroots to atrophy, or even recede from public life altogether in many places outside of very liberal areas. Since 2017, the new grassroots resistance people have not joined “the Democratic Party establishment,” but they are not just bashing it either. Many activists are looking for ways to promote reform and openness — while increasing ongoing citizen engagement with party candidates and officeholders at all levels.

So in the spring of 2020, broader societal fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic might scramble whatever historical trajectories thoughtful political scientists have been tracking over the past couple years. But given that the former outsider Donald Trump now can campaign boosted by a realigned Republican Party operating on his behalf, and given the ever-present possibility for an anti-Trump coalition to re-splinter across various socio-political divides, what could some most effective forms of organization look like? What most persuasive case could you make to national party leadership, for example, that it often will be both in our democratic and our Democratic interests not to have institutional elites operate as key centralized players here? And what most supportive case might you make to far-flung progressives to keep working passionately for what sometimes feel like modest, moderate gains (say in many rural counties)?

Indeed, the COVID-19 outbreak has shaken up many well-laid plans for this election cycle, and at this point no one can accurately predict all the ramifications for our society and American politics. Plans for Democratic campaigns that rely heavily on in-person voter-registration efforts and door-to-door canvassing operations may well be rendered inoperable. Democrats will have to use a blend of Internet communications and personal ties instead, and we think grassroots resistance networks might play a strong role in many places — especially suburban swing districts where women activists know how to communicate in many modalities. Meanwhile, Republican Party leaders, as we have learned in interviews and field visits, are already well-prepared to use social media alongside phone contacts to squeeze as many votes as possible out of Christian conservative networks and non-metropolitan areas. Trump himself will want to resume big regional rallies, but might do it too soon and thus risk reigniting the spread of viral illness. And in any event, GOP fortunes will ride along with President Trump’s dominance of television airtime to speak about the federal government’s rickety crisis responses.

The geography of this virus crisis is unpredictable, too, and could cut both ways. By summer and fall, many smaller cities and towns in Republican areas could be hard hit and overwhelmed, even after bigger cities in mostly liberal states have gotten a handle on the pandemic. But it is also possible that repeated outbreaks might discourage urban voters from going to the polls in November, especially if Democrats prove unable to orchestrate absentee ballots and voting by mail — or if GOP state legislatures bias procedures to make it hard for urbanites to vote in various formats.

At this point, it seems that many of the new grassroots liberal groups included in our studies have pivoted to mutual-aid efforts rooted in their local communities. Now that traditional campaign field organizing may be curtailed, naturally existing networks (with both an online and face-to-face component) will be more important than ever for Democratic Party organizers and candidates, just as they are for GOP counterparts. Democratic strategists will need to figure out how to build on and leverage those networks between now and the election, even as the public-health landscape shifts unpredictably.

Since 2016, especially in swing states and districts, grassroots activists have worked tirelessly in general elections — often helping to elect (as in 2018) the more moderate-liberal candidates who now make up most of the party’s large House majority. Our research on Pennsylvania shows that pragmatic local volunteers often worked very hard to elect Democrats they understood held more moderate views than their own. And experiences with canvassing also introduced many progressive-minded local activists to the varied outlooks of neighbors, including to the often very conservative views of people in swing districts and smaller cities and towns. Real-world conversations often drive home just how hard it would be in many places to advance left-progressive priorities. To this day, grassroots resistance activists are much less likely to push the Democratic Party toward the far left than grassroots Tea Partiers were to push the Republican Party toward uncompromising right extremes.

Many local resistance activists grasp the importance of this kind of pragmatic approach for advancing progressive policies, and they have kept at it. In 2020, once again, their efforts may be decisive as Democrats look for victories in geographically widespread places — victories that Democrats must have if they are to win the presidency in the Electoral College, defend their House majority, and perhaps secure a majority in the Senate.