We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics, edited by Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel, was published in November 2020 by Nightboat Books. The months since have underscored the collective nature of crisis and hope. Adaptation is ongoing, personal, and political. The pandemic continues to exacerbate bodily and civic inequality and unrest. Debates about care practices, abolition, and individual freedom expand and contract as circumstance and technology compels more of us to confront the rough allocations of resources and justice on which we build our lifestyles.

We Want It All kicks off with “MAKING LOVE AND PUTTING ON OBSCENE PLAYS AND POETRY OUTSIDE THE EMPTY FORMER PRISONS,” an introduction whose title — drawing from Bernadette Mayer’s 1984 Utopia — speaks volumes. Anthologies at their best are as much impetus as archive and We Want It All is momentous, with contents ranging from iconic texts from Sylvia Rivera and Leslie Feinberg to recent work by contemporary poets. The book looks forward while reminding us that poets have long been calling, via love and obscenity, for a better future present.

On the anniversary of the book’s release the editors talk abundance, social texture, and worlds to win.

¤

K.B. THORS: We’re coming up on a year since the book came out. Times continue to be intense. How do you feel about the project and its journey out into the world?

KAY GABRIEL: One thing I’ve thought from the start is that our aim for the book wasn’t for it to be a handbook for perfectly understanding a single moment in time. In the face of crisis and constant flux, the building up of some social forces and the dispersal of others, we have to constantly revise our understanding of the reasons why, as Gwendolyn Brooks writes, “what / is going on/ is going on.” I’m sort of perverse in that I think poetry is one thing that helps people do that. It’s not the only thing, and it’s not the most scientific. But I think about poetry as a genre — because of its relatively low barrier to entry, because of its porous relationship to language, because it doesn’t have to be mired in a certain kind of dead empiricism that forces it simply to describe the bad world that already exists although it can deploy a realism in the sense of demonstrating a writer’s “access to the forces of change at a given moment of history” — that enables rather than disables response, reflection, thought, collectivity, and that makes all these things converge together rather than be experienced in little cells of private feeling. One thing I personally wanted for the book was for it to deepen this kind of responsiveness. It’s impossible to quantify whether or not that was successful, but I feel good about it.

Just to say another thing: it’s fascinating that Andrea and I edited, and our contributors collectively wrote, a really staunchly anti-capitalist book, full of certain kinds of raunch and humor, a series of really torqued uses of language, and just trans people being louche, gross, loud, expansive, biting, and mean. And it really met with a much warmer response than we could have imagined. To me, that’s sort of an interesting experiment, and it suggests that the alignments we’re tracking — between a resurgent anti-capitalism, emergent trans culture and the ongoing practice of poetic experimentation — are real and deep and touch a nerve with people, not all of whom are trans, or poets, or were previously politically activated.

ANDREA ABI-KARAM: It’s been amazing to see the wideness of the anthology’s reach over the last year and the particular enthusiasm and hunger for radical trans writing that’s messy, celebratory, sexy, and belonging to multiple genres and registers. We Want It All has been reprinted three times since the release, which feels utterly momentous for a 480-page bright pink brick. I’ve also been surprised at the different types of spaces and conversations We Want It All has travelled through. I have a friend who is studying intimacy coordination, working with TV and movie actors who film sex scenes, and We Want It All is on their syllabus. There’s this mutual aid org that organizes and offers free post-op gender affirming surgery care in New York and the Bay Area, QueerCare, that I volunteer with, and they featured We Want It All in their eblast as something they were excited about without me even bringing it up. We Want It All being a part of these types of spaces centered on the intimacy and immediacy of the body, sex & surgery, spaces that are very much outside of poetry is really exciting.

Sweetness runs through this work. Ari Banias writes of “Withstanding / the two camps / a sweet third.” Bryn Kelly’s “Diving into the Wreck” quotes Frances Goldin’s activist advice: “Your life will be made sweet by comrades and friends.” Clara Zornado and Jo Barchi’s epistolary “Correspondence on Erotics and Karaoke Rooms” declares “I am sweet and brazen.” Can you speak to the sweet in and of this project?

KG: I’ll respond personally here. Like Goldin, I’m a Jewish communist. My Judaism gives a lot of structure to my communism: it inflects how I think about the limits and possibilities of change, it gives me narratives within which I perceive events and changes in social relations, and it maybe also offers some norms that I’m particularly receptive to. So for me, sweetness, in Goldin’s use, and then in Bryn’s quoting Goldin, has this particular ring to it. Like, on Rosh Hashanah, we say l’shana tovah u’metukah — “a good and sweet new year.”

Goldin’s addition: she makes that sweetness collective. Listen to that line: “your life will be made sweet by comrades and friends.” She puts the comrades before friends, and the sweetness happens, so to speak, in and through political activity. And what does that mean? Maybe the sweetness is an effect of the joy and pleasure of being in struggle with people, but maybe it’s also because of winning changes in conditions to your own life and the lives of people around you. Goldin was someone who successfully helped to organize working-class people on the Lower East Side to prevent Robert Moses from building a highway through their homes. I think in this regard about the successful eviction defenses, and successful rent strikes, of the past year, which have been bright lights in a pretty dark moment of rising legal and illegal evictions: when we win the ability for people with very few resources to stay in their homes, everyone’s life is made sweeter. And you can come up with other examples like that. So that’s how I think about sweetness.

The other thing I think about here is actually an understanding that the book pushed me towards — I couldn’t articulate it before Andrea and I edited the project. And that’s the understanding that abundance is a structure of feeling, in Raymond Williams’s sense. Wililams’s 1975 Marxism and Literature introduced the category of “structures of feeling” — narrative structures by which people at scale understand and respond to the social forces in flux around them. And one thing that came out over and over in the book is a shared sense of abundance produced by and transmitted through various poetic devices. Like “sweetness,” abundance isn’t just or mainly a matter of material plenty: instead, it’s a shared sense of collectively developing the power whereby people with very few resources get what they need. And if this sense indicates a kind of possibility that allows people in crisis to feel something other than entropy and powerlessness, then transmitting this structure of feeling is something that poetry does really well.

AAK: This question makes me think about the unrestrained nature of queer friendship and how removing certain types of bounds that identify relationships as either romantic or not-romantic allows for so much possibility in collective connection and experience. Queer and trans friendship is made possible, as Kay mentions above, by abundance and that the embrace of this excess is in direct refusal to the impositions of late stage capitalism that seeks to separate, isolate, and ultimately work to death. If certain pleasures can be reveled in across many different forms of relation more and more collective pleasure becomes possible. The epistolary is one of the many forms in We Want It All that celebrates this openness in divesting from the limited singular experience — conversations and correspondence are collaborative processes and whereby we get to enjoy the erotics of queer friendship across time and space.

“My fate is to be well taken care of” asserts Logan February’s “Girl of the Year,” a poem whose speaker has “a wealth of headaches.” Ray Filar outlines an excruciating health care process: “I have waited four years, not for an official medical prescription…for a conversation in which I try to prove I deserve it” (“You’ve heard of Ritalin, now what if I told you governments make bodies into crime scenes for no reason at all.”) How does this work collide with current health practices? Can collected writings expand popular perspectives on equitable care, or are they more like venting sessions among those who can relate?

AAK: In both February and Filar’s pieces is an astute critique of how capitalism structures healthcare. The way health and care has been made transactional, where practitioners’ time is optimized for volume of patients so more insurance can be billed is a disservice to patients and providers alike. Navigating the healthcare system is a vexing process, and extremely so for trans people, there is a constant and repetitive push to define yourself on the institutions’ terms which is exhausting but in order to get what you need you more often than not have to bite the bullet and do it. I love Filar’s piece since it zooms in to this particular effect of capitalism on healthcare simultaneously with their refusal to fit neatly into what they want or expect from them — but they want and need something — even if they’re not 100% sure they know what it is yet, they show up with the contours of a body that shifts in multiple directions, and in order maintain their relevance to capitalism — they need Ritalin to keep them going.

“If i had a job i would not commit crime,” says listen chen’s “弃智遗身.” Holly Raymond’s “Secret Mission Orders for Goblin Romantic” describes a “you” who is “unstoppable and demure and 10,000% fired.” How do these poems illuminate the contradictions of working, or trying to work, under capitalism?

KG: I guess I think that one thing that poetry is really good at is internalizing the contradictions of time that mark the rhythms and shifts in the transformations of capital. It’s a different way of making palpable what Marx called the “annihilation of space by time.” When trans people — statistically, highly likely to be un- or underemployed, precariously employed or working in jobs subject to intense policing and politicization — write poems as one way of addressing our situations and making them collective, we do so often if not always from the stance and perspective of a particular series of experiences of not just work but the working day. Maybe that’s because you write on the clock; maybe it’s because you’re writing from the stagnant surplus time of unemployment.

I think here as well of Nat Raha’s “(when we’re working while we’re asleep).” Nat writes: “social myth … that / if restless / we will / struggle at the premise capacity for the day due.” It’s a poem in some sense “about” two sleeping lovers; it’s also a poem about subsumption, the entry of work into the “8 hours for rest,” as the proponents of the 8-hour day a century ago called it. Is the social myth that Nat’s writing about the idea that we’ll “struggle at the premise capacity” if we’re “restless”? And by “struggle,” does she mean struggle in the sense of only barely treading water at your job, or the other, more militant sense of struggle? The poem opens up both meanings, maybe with some bite, maybe with a bit of irony about the romance of writing a poem about sleeping beside your lover, certainly with an intense desire to reclaim the day and night together for ourselves.

And so I think that’s true about listen’s and Holly’s poems as well, in different ways. Holly’s poem is from a chapbook called Mall Is Lost: it’s exquisite, and it’s a shame it’s out of print. There’s a mall, and there’s goblins — you should find a way to read it. It’s really good. listen’s poem I think is really constructed around a series of counterfactuals: “if I had a job I would not commit crime if I had been arrested I would say I was sorry,” is the line, and in a sense I think the poem is asking us to call its bluff. Like, those counterfactuals are lies, and interesting ones.

The closing couplet of Trish Salah’s “Manifest” reads “What is apparent is the ease of our death / To whom do we die? To whom wish to live?” Bigotry manifests in death; community is inherent in our personal manifestations. What does this book make manifest? Would you call it a manifesto?

KG: I don’t know about a manifesto. I think you need a cohesive aesthetic or political program for that, and that wasn’t our aim here — though certainly there are things we believe very strongly about aesthetics and politics both.

The syntax in Trish’s poem is really fascinating, when you think about it: “to whom do we die? To whom wish to live?” as if living and dying, like giving or showing, could have an indirect object — as if you could do them for someone’s benefit or disadvantage, or on display, or with an audience. Given how trans death is so spectacularized in media portrayal, the framing makes sense, even though it’s syntactically wrong. Certainly one thing that we want the collection to make manifest is all the rich social textures of trans life. We want more and more of it, open and porous to more and more people.

The introduction explains how the title We Want It All pushes “against the common-sense intuition that crisis means we must demand less.” Can you expand on how this wide scope plays with another key statement from the introduction — that “poetry should be an activity by and for everybody”?

KG: Well, it’s related to your question about COVID-19 and the long arc of the pandemic, really. In the places in the globe where state capacity had, for decades, been directed away from keeping people alive, the death rate from COVID was tremendous. The US is the worst example, of course; Brazil under Bolsonaro is another. But the crises that COVID brought to the surface antedated the pandemic by decades. Austerity budgets, the closure of hospitals and emergency rooms, deeply racialized disparities of access to healthcare, transit, and nourishing food, the intellectual property regimes that are still choking vaccine access to much of the globe, the US’s illegal unilateral blockades on Cuba and Venezuela that acted on purpose to worsen pandemic conditions in those countries, and of course landlord-tenant relations — those were all already problems, and under conditions of mass crisis, the state cracked. The wealthiest state in human history couldn’t meet the basic needs of its residents, because it’s been, over the course of the past several decades, designed not to be able to meet those needs. There’s a version of this answer that relates to climate crisis as well: the wrong thing to ask for is the return to the rampant dispossession and meager distribution of a couple decades ago. Instead, we have to ask for what we need to live — everything that we need to live — and we have to do so in a way that addresses what led to this problem in the first place.

So what does that have to do with poetry? There’s a real universalism in our project here, and one of the things that we insist on is that the sweetness and abundance we were talking about above — those things belong to everyone, and in particular, to people who have been deeply dispossessed of the latitude, resources and power they need. And when we say they belong to everyone — in some sense, that’s a speculative claim. It refers to property and class relations that don’t currently exist, but could, and if we’re effective, strategic, and lucky, they will. We have a world to win, and for us, poetry is a part of that process.

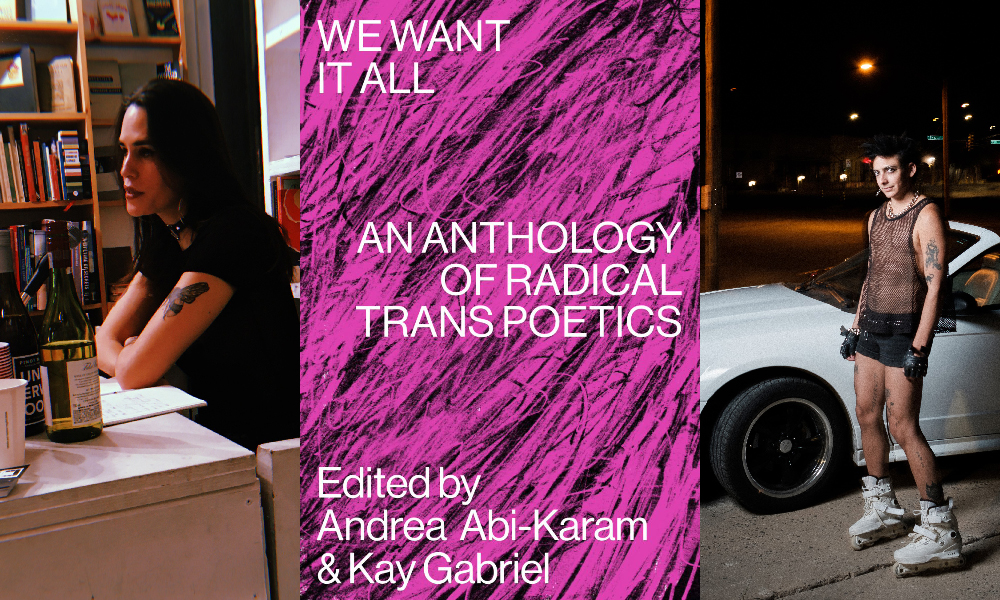

Top Image: Portrait of Kay Gabriel courtesy of Jo Barchi. Portrait of Andrea Abi-Karam courtesy of Julius Schlosberg.