Abdellah Taïa was born in a public library and grew up in Salé, the poorer, twin city that sits across the Bou Regreg River from Rabat. Though he now resides in France and hasn’t lived in Morocco for almost 20 years, it still figures largely in his fiction, which is often about “that specific time at the beginning of adolescence when […] you see what they want you to be, and how you are going to escape it.”

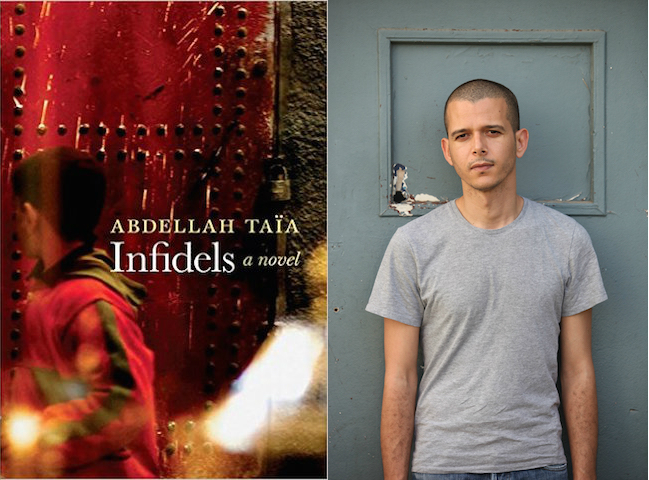

Taïa is frequently introduced to English-language audiences as Morocco’s first openly gay novelist, a title he feels ambivalent toward, as it often leads people to view his work more through the prism of social science than literature. Infidels, his most recently translated work, is the story of a Moroccan prostitute Slima and her son Jallal, who is very much in the throes of the adolescent transformation which Taïa describes. Jallal’s sexuality is more ambiguous than the young male characters of his earlier novels — ambiguity, Taïa says, is a concept that defines Morocco. The reader is unsure how sexual his feelings are toward each of Slima’s clients, who, in many ways, function as a rotating cast of father-figures for Jallal as he navigates the ostracism and loneliness that comes along with being seen as the bastard child of a prostitute.

Jallal moves to Belgium and grows close with a convert to Islam named Mahmoud. Jallal is hypnotized by his love and admiration for Mahmoud, and though Mahmoud reveals very little about himself, Jallal soon finds himself devoted to his new companion. Haphazardly, he falls into partnering with Mahmoud in a terrorist plot to detonate a bomb-strapped vest in Casablanca. Hours before their plan is to be enacted, the two are discovered, and, with their original scheme thwarted, they detonate their vests in an empty movie theater and travel together to heaven.

In just 144 pages, Infidels attempts to thread together poverty, gender and sexuality, a coming-of-age story, Islam, immigration, and terrorism. Taïa is insistent that he is influenced by his own lived experience, and considers questions about other influences — particularly literary European ones — a high-brow obsession at odds with his upbringing in a poor, Moroccan family.

Taïa’s cadence — what he calls “written musicality” — is one of the most distinctive features of his writing. He strings together short, terse sentences in a way that brings drama and forces readers to feel the weight of his characters’ loneliness and anxiety. He speaks in a similar cadence, pausing frequently and repeating words for emphasis. His thoughts move according to the natural rhythm of his uncalibrated stream-of-consciousness, rather than any formula. “Creative and real. Real. Not abstract,” is his aim, he says.

This month, a Moroccan publisher, Tangier’s Librairie de Colonnes, will publish an Arabic translation of one of his novels for the first time, Un Pays Pour Mourir (A Country for Dying). Taïa says he feels nervous. In April, the English translation of his novel Another Morocco will be released by Semiotexte. On April 12, Taïa will join Steve Reigns in conversation as part of LA Public Library’s ALOUD series.

The following interview, conducted in English and French, has been translated and edited for length and clarity.

When Slima’s client, the soldier, is leaving Salé to go to combat, Jallal says longingly: “My mother didn’t care. For her, he was just another customer among so many others.” Where does your interest in writing about atypical fathers figures come from?

ABDELLAH TAÏA: This is coming from my family. I didn’t grow up with everyone playing the roles society asked them to play. My father is extremely tender, extremely weak, and extremely romantic. There is always some tenderness and absent father figures in the book. Because Jallal has no father, I think, he has to choose his own at some point. But when he chooses, it happens in a very non-traditional way.

So, what does it mean, this whole thing? I think deep, deep down, the way I see society, there aren’t fathers. It’s always mothers who keep things up and going on. Always women. The fathers — men, in general — are always absent or disappointing. Always. It’s women, when it comes to dealing with reality.

But again, fathers, they are always a little bit, in my case, tender. I don’t want to treat them more harshly than reality.

You write about the “introductrice,” a woman who helps guide men and women through sex on their wedding night. She advises a woman: “If sexual words aren’t enough, and your eyes and buttocks have no effect, then brave girl, without asking, put your finger in the groom’s asshole […] Men love it. Love to be treated in a different way. Love for the tables to turn without warning. They like the asshole, their own, other people’s.” This is an unexpected passage about role reversal and the unspoken. Is this shedding a light on something that’s “real,” as you say?

The introductrice is a real role in Morocco. I know someone whose grandmother was one. I didn’t invent it. Slima, [the introductrice’s daughter and] Jallal’s mother, is continuing something that has existed throughout history. In Moroccan society, there has always been someone who is “introducing” and helping on the wedding night. In all countries, there’s marriage, but when you dig a little bit further, there are always other things going on. People won’t admit it, or talk about it, but this scene is me exposing Moroccan society. They would say these things don’t exist, but they do exist.

Her character says so many things about Morocco, and specifically about things that are hidden. Of course, there’s some queerness in her as a character, like in so many things that I write. I’ve always talked about these kind of people; I think this is what makes me “queer” somehow. I don’t know that much about queer theory, but for me to be queer is to look at society and to talk about the people who are already in another place, but one that no one recognizes. It’s already there. It’s just that I have to recognize and write about it. But not in a sociological way, but in a literary way.

What’s the difference? And why do you go about “recognizing” these things in a literary way?

Because I’m not a sociologist. Even if I wanted to be, I don’t have the techniques or training to analyze society in a sociological way. But I can recognize a character. When I hear some things, I know they have to be in my book.

As a writer, I know what to take from life and what to steal from people to turn into literature. To be this kind of thief, it’s a talent. Not everyone can be a good thief, but I think a writer is a good thief. You take something, you nourish it over many years, and turn it into something, I hope, with some literary value.

How does it feel when people look at what you do from an academic perspective? You’re not a social scientist, as you have said; you write fiction, and I think it’s important to look at your work as fiction, on the same plane as other novelists.

Yes, I totally agree. But, when it comes to LGBTQ subject matter, because there aren’t so many people talking about these things freely, just the fact that I talk about it at all takes all the attention from the “literary” nature of the work.

From this, I have two reactions. First: what can I do to change it, and how am I going to make people see my books as literature? Second: it’s very important for me as a gay person not to shy away. When people try to put us in the [gay] box, I think it’s their problem. Because it’s still very important for someone like me to talk about human rights for gay people in Morocco and in the Arab world, because there aren’t people talking about it that much.

So, you see the problem. When I was young in Morocco and I talked to people about literature, they saw it as something that had nothing to do with their reality. So with my writing, people said, “well he’s talking about things that we know”; people told me, “This is not literature!”

For them, the idea is that literature is elsewhere. It’s not us. And even when you try to say something nice and constructive about your own people — your own people, who are suffering from submission, political and otherwise — they don’t see it. They say, “this is too easy.” They say, “He’s just témoignage [witnessing].”

“It’s easy, so he’s not a writer.” Because I’m talking about my family and my neighborhood? Because the subjects are about the poor, they are therefore not literary? Even the poor think they not worthy as literary subjects. Colonialism succeeded in telling Moroccans their stories are not worth telling. It’s extremely sad.

What are the implications of this phenomenon?

In school in Rabat in 1995, when I started to write, the things coming out of me were things coming from my life, especially from poverty. People were expecting me to write like Victor Hugo. Like Marcel Proust. And to say sensitive things in a very complicated, French way. But I wrote about things from my life, not from books that have nothing to do with my reality. But still, the idea in Morocco, until now, is that literature doesn’t tell us much. And if it does, it tells us in a complicated way that shouldn’t be accessible to everyone.

You see, in society, everyone reminds you of what you have to do and what you have to write. You have to write in a very complicated way, like the French writers. Or you have to “name-drop” or link yourself to some literary legends from Tangiers.

You’ve often been asked about these writers from Tangiers — Paul Bowles, William Burroughs, Brion Gysin, Jean Genet — and you respond similarly each time.

I have nothing to do with William Burroughs or any of these people. Why should I be linked to these people? It’s only because I’m gay, but I learned about them in my 20s. They don’t have anything to do with my life. Their reality — what they looked for in Morocco — has nothing to do with me.

It’s not that I don’t like these people, to be clear. William Burroughs and Paul Bowles are huge, even if I have some feelings about how they treated Moroccans and Morocco. When I read their books, I see the literary value. But I grew up in the poor Morocco. These people and their realities were far removed from my own and I didn’t even know about them. So why should I now make links about things that didn’t exist in reality? It’s not that I don’t like them. But I feel that the older I get, the more I see that it’s the reality of Morocco that dominates my books, one that includes homosexuality. I write portraits and images of Morocco.

In these portraits and images, what are you trying to capture?

The sensibility and imagery of religion, Islam, and popular culture that we all share. And the mechanism of Moroccan society — the political, the sociological. And a Moroccan person who tries to succeed, to save himself in this very complicated reality.

I think this is all in my books and I think Moroccans can relate to this very easily. Why they don’t accept it — for the ones who don’t accept it — is because, for them, it’s a gay perspective, from a gay person, and it should not even be allowed. So they stop. They reject it by saying, “this is only about gay people. About a guy selling his bottom to the west. We don’t want him.”

So there’s this artificial choice, as though you can’t be gay and Moroccan at once. Do you think, when people look at your work, they look at it in both lights?

No, most look at it as “this is a gay — not even writer — this is a gay guy who wants to impose on us his dirtiness.”

You approach to Infidels is similar to your earlier novels, but you’re now writing about terrorism. And in the context of Jallal and Mahmoud in particular, subjects — like homosexual love and terrorism — are blended together in very unexpected ways. How do you think this portrait differs from the portrait of a “terrorist” we generally receive today?

There isn’t good or evil in my books. Most of my characters, the heroes at least, are not “good.” But just to make people see this, I feel like I have to say it. They don’t see it, even though it’s in the book. I try to make complex characters.

First of all, when I gave the manuscript of this book to my publisher, Le Seuill, in France, some people had real problems with it. They wanted me to condemn terrorism by saying that this guy was a bad guy. But not only did I not say Mahmoud was a bad guy, I allowed him to go to heaven, with Marilyn Monroe and with his lover.

In society, our monsters are like us. They are as human as we are; they love, they have love stories. Even when they veer towards extremism, there are things in them like us. To present them in the literary work as evil is not the right thing to do. If I do that, I’m following the ideology that says who the “enemy” is. The “enemy” is always changing. I told myself that I should just try to write sincerity and monstrosity and with extreme ambiguity. An ambiguity that anyone can relate to.

What do you mean when you say “ambiguity” and where is this coming from?

For me, Morocco is a country of ambiguity, and Moroccans are masters at dealing with it. They can act as one character in one moment, and then in other situations, give you another face. They are masters of this! I lived with that. Even as a gay person, I had to master it. This is something I dealt with and am still dealing with, even here in France, and I think that it’s something that should be in literature. Not mannequinism. Mannequinism is for political people who want to win elections. Reality is always much more nuanced and ambiguous.

The truth, the real, is very important to you.

The real, not the truth. When I say “true” it means “real.” It has to feel real. For me, reality is always ambiguity. Always. Not only in regard to people who are doing bad things, but even us. Even me as a gay person. It means that in dealing with life, there is no black and white. This is ideology.

Ambiguity is a literary technique that you use in order to describe what the world is and what stories are about. I try to do less in order to show more of Moroccan reality. I didn’t find this in literature, I found it first in Morocco, in reality. And as a gay person.

Does your perspective change as you mature as a person and a writer?

No, my perspective does not change. What changes is the style. The style evolves. But me, who I am, I think I stay the same; a very pessimistic, desperate person, very dark inside. Although I don’t like that. But inside of me, that’s how things are.

My dream is to write about the craziness going on in the whole world, in our daily life. Not everyone is willing to admit what we are forced to do every day in order to live in this society. The dream for me is to be the darkest possible, but I fail every time. When I finish a book, I’m afraid to even read it because I feel like I wasn’t dark enough. I should be darker.

But is that a failure you savor? Because there’s a balance. Your books are very dark but there’s a hope you seem to not stem out.

Well, what can I do? There is always something romantic that comes out a little bit hopeful. But I don’t know where that hope comes from. I don’t know where. But, still, I totally agree with you that in the pages of my books you see instances of hope showing up and imposing themselves on the story and on me as a writer. Frankly, I don’t see where they are coming from. I don’t see the hope in my life.

I’ve read that you think in Arabic while writing in French. Some of the passages in Infidels that I find most memorable are those when you are translating, when there’s a word in Arabic and you unpack it. It’s interesting, as a reader, to see your dialogue — you translating the Arabic to your French readers — while also knowing that Allison Strayer translated the passage from French to English. Do you think of yourself as a translator of emotions and sensibilities that originate in Arabic into French?

Not translating. I feel like there’s more of a chaos of languages in me. Things mixing with each other and producing what’s in my books. I don’t think my language in French follows a French literary tradition. I think you would feel in it some sensibility coming from Moroccan life, spirituality and imagination. There’s something spiritual in my books.

It’s a mixture of all these things. And that’s why, I told you, some people don’t get it. They don’t see what I do as literary work. My phrases and words, for instance, are very simple.

Can you tell me about your writing of very short sentences?

The more I write, the shorter the sentences are. They are short because there is more musicality. In my head, and in the paragraph.

I don’t see myself going into a maze, a labyrinth, which, for me, would be a French literary style. I think, because I didn’t read those French classics when I was little, it’s impossible for them to have an impact on me. They didn’t change who I was deep inside. Deep inside who I am is someone who lived with poor people with no desire to be pretentious. I think in my language, there is something still poor, when it comes to words. I feel like I only have few words in me.

It’s just like a Moroccan family who has nothing, but when a guest comes, they invent something just to give them. When they have nothing! I don’t know how they do it, but they manage to change that little thing they have into something — not beautiful or tasty — but with some meaning that will make their guest feel honored. I think that’s the right image.

That’s an interesting comparison to writing.

But for me, I still feel poor. Not poor as in ashamed of being poor, but I feel poor because this is what I put in my head. It doesn’t stop me to be “poor” in this sense. I’m here in Paris, but in my head deep down there is still this imagination, this sensibility, this poor person’s imagination. So, I don’t have many words, but yet I think I’m crazy enough to tell myself I’m going to write a book with these things I have.

When you were saying your perspective comes from growing up in poverty, it made me think of Moroccan Prime Minister Ben Kirane, who brands himself as “of the people” and is known for speaking in a very folksy way. When you say you write from a perspective of poverty, do you think that’s different than populism?

Absolutely. Because populism is using proud words in order to play with people and somehow lie to them — not to connect people to reality.

Me, I’m talking about naked poverty. True poverty. And plus I am gay, meaning, whether I like it or not, I am speaking from a place of transgression. Just the fact that I write. That I talk about the kind of people in my books. They don’t want me to talk about these things. But they hear me talking about these things.

After the attack on Pulse nightclub in Orlando, you wrote in Liberation: “Even in the West, the political struggle for the cause of gays has not yet been won.” How have these tragedies affected you?

We see that gay people still need to be defended. Gay people are just people, but at the same time gay people, in the world we are living in, even in America today, even in democratic countries, are still not that safe. It’s still not as accepted as we think it is and somehow it’s like being a Muslim. It’s like being a Muslim in the West. When you are seen like that — you’re the new fashionable enemy, for some people.

Do you see those as similar, in how people approach you?

Yeah. When I was little I developed strategies to hide the fact that I was gay, because if people knew, they would harm me, they would insult me, they would beat me, or whatever. So I had to be always scanning the world for dangers. And I cannot help, here now in France, but to keep using these strategies. But now, I am seeing people see me as a Muslim. Women or men pass and you feel the tension. Or some women in the subway, they jump onto the train and clutch their bags. You see it. It’s a reflection of what is happening politically. Suddenly, to be gay isn’t a signal to being free. It’s not enough. People see me mostly as Muslim.

People can’t see you as both?

Maybe next time, when I’m on the train, I’ll say, “Okay, I am Muslim but I am also gay. Please. Forgive me!” My technique now is I have Le Monde and read it. “Okay, I’m Muslim, but I read Le Monde!”

In Infidels, the way you write about characters about to carry out a terrorist plot is similar to the way you write about gay characters in your other novels. They struggle with loneliness, their identities, they wander.

So maybe that’s my true revolution. I’m putting queerness everywhere. My own definition of being queer is to change, to put people in another light, in another place. By talking to them at the same time. Isn’t that what art is supposed to do: to bring a new light on old situations? To go to another place with the same people? To be gay, but with your mother next to you?

For me, it’s much more interesting and challenging and frightening and scary to be gay next to my mother — even though she is dead now, but she knew I was gay — than to go to a gay bar. It’s much more engaging, especially in my books.

Your gay characters never go to gay bars.

You will never find these things in my books. This is very important to me: not to bring what’s obvious.

Is Jallal openly/outwardly gay in Infidels?

In the beginning he says he’s in love with the soldier who’s a client of his mother’s. And there’s the passage where he goes to the house of the soldier and cleans the house.

But it’s ambiguous. Is he a father figure? Is he an erotic father figure?

Well, again, there’s nothing totally defined. But what was interesting, when I had him meet Mahmoud, was this identity imposing itself on him. Not all gay people would connect with that; learning Arabic, talking about Islam. Most people, when they think about gay people, think of people that free themselves from Islam, from authority. But not all gay people live their homosexuality in a Western way. I’m sure there are other love stories, gay love stories, happening in the old cities, between people who go to mosques.

What does this mean? It means we all live with some contradictions. We are not clear with ourselves, and even when we know that the things that suppress us are bigger than us, we cannot free ourselves from them immediately. But these contradictions do not mean that the love we live is not sincere. When you talk about a gay character who comes from the Arab world, what is expected of him — from a Western perspective — is that he’ll say, “Fuck Islam, fuck Arab countries, it’s all bad things happening there.” But it just can’t be this blunt image. Reality is more nuanced.

Clearly in the book, Jallal and his mother want to get revenge on Morocco. Because Morocco treated them very, very badly. Jallal’s desire for revenge meets Mahmoud’s radical terrorist project. They converge, but Jallal doesn’t see it coming. This is why some people didn’t accept it: true love combined with a terrorist project.

The word “naked” figures largely in the book, and I think it means many different things. Naked is real, exposed. Where does this come from for you?

You live in Morocco. You see what happens within homes, in hammams. There is this idea about what has to be covered, what has not to be covered, what we say, what we show to others, what we don’t show. And the desire, for us, at some point, is to just forget about all these things and to show the true self.

But, before this metaphor, I think it comes just from the home. I used to see my sisters change their clothes in front of me. My mother used to change in front of me. So, I saw naked bodies I wasn’t supposed to see, but I wasn’t supposed to talk about it. And, because what happens between people, between people’s bodies — including and especially family — are many things that we don’t speak about much. For me, before the metaphor, it’s this.

So you build a metaphor off of this? Does this metaphor signify a transgression?

Yes. I think we learn sex, we learn love, from the family members we live with, because those are the figures we have in front of us over the course of many, many years. Their bodies express so much that is unspoken, and these things enter us and change us and shape our desires, our way of being — socially, sexually, politically. Of course, if we say this in real life, no one will accept it. But I think as a writer I see this clearly. I think literature, it loves this—to witness this first nakedness. People will not admit it, and that’s fine in the social life. But when it comes to literature, you have to be there.

When you say you write from life, whose life are you talking about? I feel like a lot of your themes are relevant to everyone, but I mostly hear your work described as specific and not universal, about, let’s say, being gay or being Arab.

This is important. It brings us back to the beginning. Whatever I say, I have to prove my intelligence, and whatever I do, I will still be the exotic, Arab, gay, Muslim boy. What can I do? When I write books, I feel like I have a world, an imagination, that I can write from, and in the middle of that imaginary world, there are so many things, and among them is homosexuality. That’s what I do. Because that world looks so exotic, and when we say exotic, we mean surrounded in ignorance. It’s very hard to escape that exoticism. But what can I do?