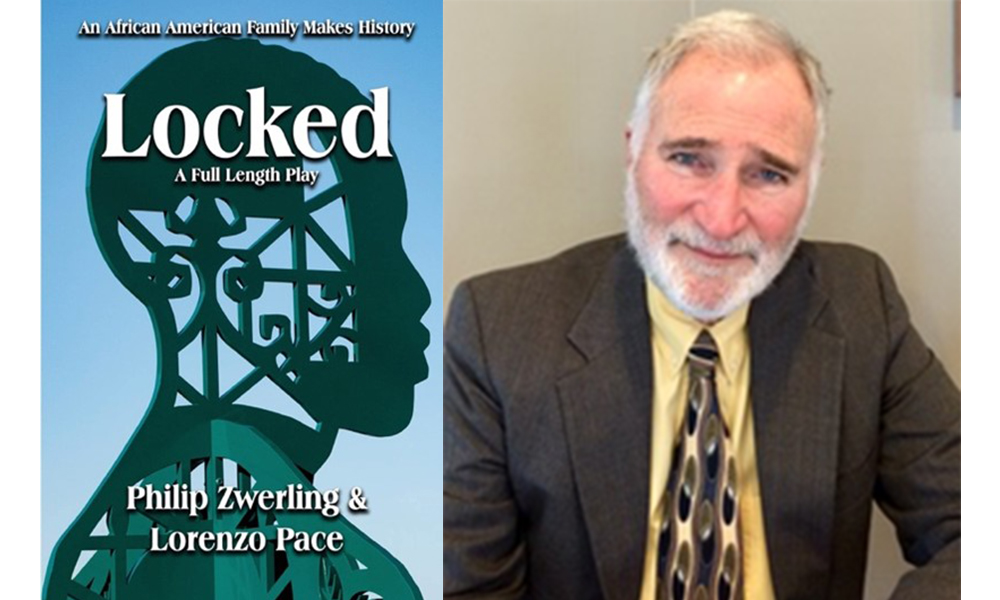

I talk with Philip Zwerling about life, teaching, activism, and the politics of his art. Prior to teaching, Zwerling served as Minister of the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles from 1978 to 1989. Changing course, he went on to earn an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of New Orleans in 1998, a PhD in Theatre from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2003, and taught creative writing at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (formerly University of Texas–Pan American) from 2004 to 2018. He is the author of numerous books including Nicaragua: A New Kind of Revolution (1985); After School Theatre Programs for At Risk Teenagers (2007); The CIA on Campus: Academic Freedom and the National Security State (2011; Editor); The Theatre of Lee Blessing: A Critical Study of 44 Plays (2016); and, with Verne Lyon, Eyes On Havana: The Memoir of an American Spy Betrayed by the CIA (2017). His newest play, coauthored with artist Lorenzo Pace, is “Locked,” available from Lamar University Literary Press.

¤

MATHEW BETANCOURT: I consider you a friend and mentor, but if I’m being honest, I don’t know that much about your background. Where did Philip Zwerling grow up and what was family life like?

PHILIP ZWERLING: My parents’ ashes lie now in my backyard in northern California. They’ve come a long way from the Bronx where they grew up and where I was born. After serving in the Army Air Corps in World War II, my father moved our family of three to a little tract house on Long Island to enjoy the American pleasures of home ownership, green lawns, and safe neighborhoods. As children we walked to school, played ring-a-levio in the street and ran wild in the woods when school let out. “Father Knows Best” and “Leave It to Beaver” resided on our street in every new black and white 18-inch TV set. We had no Black neighbors, no Latino neighbors, no Asian neighbors, and no understanding of anyone who didn’t look like us, live like us, or think like us. Somehow our lives were simultaneously rich and poor in experiences.

A Harvard graduate once told me it was easy to spot others just like him — Harvard alumni always wore bowties. I’ve never seen you wear a bowtie. When did you attend Harvard, what did you study, and what do you remember most about your time there?

The one oasis of diversity and inclusiveness when I was growing up was the Unitarian Church, the place where I encountered my first vegetarian, my first Chinese friend, and the first people who had no fear of differences. For me it was a liberated safe space I experienced nowhere else in the straitjacketed (bow-tied?) 1950s. In the 1960s I chose a college (St. Lawrence University) with an historical connection to Unitarianism with the idea of becoming a minister. I spent my time on campus at SLU organizing their first SDS chapter and trying to burn down the ROTC building. I went off to Harvard in 1970 to earn a Master of Divinity degree and begin a student ministry in nearby Ashby. Rather blindly, I almost burned that place down, figuratively speaking, when our Church celebrated MLK Day by introducing a seemingly innocuous resolution for the town to declare itself a welcoming community for all races. The ensuing debate made national headlines when the residents defeated the motion at the annual town meeting. NPR recently did a story on that decision 50 years later.

In the 1980s you served as Minister at the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles, and in 1985 you published your first book, Nicaragua: A New Kind of Revolution. Describe how religion and geopolitics came together for you during these years, and how it impacted your work with the Los Angeles community of the time.

When I was called as minister to the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles. I joined a hundred-year-old church with a history of political activism. Los Angeles was then and is today a microcosm of the world, where schoolchildren come from homes speaking 123 different languages. Our church instituted simultaneous translations of services into Spanish and Korean and hired Korean clergy and Salvadoran outreach workers. At the height of the US support for fascists and death squads in El Salvador we created the Sanctuary movement for refugees in Los Angeles in alliance with six other congregations of various faiths. The FBI and LAPD snuck around our church taking notes and filling dossiers.

One transcendent experience for me came on a sunny Sunday morning in the early 1980s. A family of four Salvadoran refugees including two little girls lived for months in our church basement to avoid deportation. I had invited Judge Robert Mitsuhiro Takasugi to speak that day because of his role in protecting civil liberties as United State District Court Judge for Los Angeles, the first Japanese American ever appointed as a federal judge. I didn’t know his personal background. He stood in the pulpit that day facing the congregation and that refugee family and said, “It’s good to be back. When I was 12 years old my family and I were forced to leave our home and were interned at the Tule Lake Camp, just a few of 130,000 internees forcibly relocated during World War II. When the war ended and we were released, we had no home anymore. We had no place to go. This church took us in and we lived for months in this basement until we got back on our feet.”

I was shocked. History was repeating itself. It struck me so strongly in that moment that social change grounded in religious belief and racial inclusion has profound effects through generations.

Through our diverse community I was able to make contacts in other countries and lead church groups to places like Grenada, El Salvador, Nicaragua, the Soviet Union, India, China, and (to meet Korean dissidents) Japan. I realized then that working class and oppressed people in the US have more in common with working class and oppressed people in, say Guatemala, than they do with the 1% in their own country. When we sat down with the relatives of disappeared activists in a little house over 1,000 miles from Los Angeles on the outskirts of Guatemala City we shared more life experiences and aspirations than with many of the residents of Beverly Hills just 10 miles from our own downtown church.

Your awareness transformed into activism during this same time. Alongside celebrities and blue-collar workers, you rallied against some of the major issues of the 1980s, including nuclear power plants following the disaster at Three Mile Island in Middletown, Pennsylvania. Why is activism important? What similarities/differences do you see with the activism going on today?

Activism, so called, is just about people acting on their deepest beliefs. When we took that Salvadoran family into our church for months at a time we had to organize well over 50 people who were willing to give up days off and nights in their own beds to be physically present to protect that family. And each of those 50 learned more about the struggle in El Salvador from that family than they ever did from our own government and press. Changed by that experience, or the experience of helping Takasugi family thrive after internment in a concentration camp, these folks became ambassadors and builder of a better society.

One astounding note of change and continuity is that just as Robert Takasugi became a Federal judge, the little girl in our Salvadoran refugee family also grew up, went to law school, and became an immigration lawyer to help other refugees and immigrants.

In 1993 you left your ministry to pursue graduate degrees in Creative Writing, specifically a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and a doctorate in drama. Why? Where did this change of course originate? How difficult was it to make this decision? Any regrets?

How lucky I am — we are — to live long enough to contemplate multiple careers. After 20 years in the ministry, I went back to school and earned an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of New Orleans and a PhD in Drama at the University of California, Santa Barbara. I hated school as a child and even as an undergraduate at college: the boring lectures, the rote assignments, the need to satisfy requirements before taking electives. But when I went back to school as an adult I loved it. I studied on campuses where I could actually follow my bliss, as we used to say. Each campus had extraordinarily rich resources: huge libraries, students from all over the world, and teachers who were experts in their fields. I could study about the “Theater of the Oppressed” and then take workshops with its originator, Augusto Boal. And having studied with him I could work with community groups of at-risk teenagers and see how theater impacted their lives. And then I could write about those experiences in my second book, After School Theater Programs for At Risk Teens.

I’ve loved both vocations. No regrets.

I met you as an undergraduate student in one of your creative writing courses at the University of Texas–Pan American in Edinburg, Texas. What did you enjoy most about teaching in higher education? What don’t you miss?

You teach because you love seeing students light up when they are intellectually stimulated and moved to consider themselves and their world in a new light. You teach because you see students grow intellectually and emotionally and meet and conquer challenges they thought were beyond them. That’s what I loved about teaching. But the reality is that at the university level you only get to spend 10% of your time with students. The other 90% is spent on administration, placating deans and provosts, and inventing statistics for so-called “assessment,” all of which is a waste of teachers’ time. Guess what I don’t miss in retirement.

In 2014, Eric Bennett claimed that the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, arguably the most influential force in modern American literature, was profoundly shaped by a CIA-backed effort to promote a brand of literature that “trumpeted American individualism and materialism over airy socialistic ideals.” You’ve written extensively about the CIA’s infiltration of higher education through subsidies and grants. Why is this subject so important to you?

Historically the CIA is one of the most destructive organizations on the planet: assassinating other country’s leaders — or trying to repeatedly in the case of Castro — overthrowing governments (e.g. Guatemala, Iran, Chile), and spying on Americans, compiling dossiers, and imperiling individuals’ employment and safety. I first ran into CIA officers in Panama and Nicaragua in the early 1980s where they were training insurgents and sponsoring targeted killings of civilians.

When I got to the University of Texas (then UT–Pan American, now UT Rio Grande Valley) I found the CIA already there sponsoring courses, offering degree programs, funding study abroad programs where students could play spy on their host countries. Their greatest need is always new personnel, and they were mainly on campus to recruit our students into careers they would rue for the rest of their lives. We organized a faculty/student campaign that successfully ended that connection. Our book, The CIA on Campus: The National Security State And Academic Freedom was written as part of that effort and to warn faculty and students on campuses across the country of the CIA danger to our democratic institutions. One contributor to the book was former CIA Case Officer Verne Lyon who was recruited off the campus of Iowa State University in the 1960s and then went on to spy on fellow students and faculty and serve abroad in Latin America as both spy and saboteur. So, a few years later, he and I told his story in Eyes On Havana.

When we get the CIA (and DIA, NSA, etc.) off campus we will have freer campuses and more critical thinking students.

Arthur Miller once said, “Theater engages audiences like no other art form.” What is it about theatrical writing that excites you most? For non-theater goers, explain why a play about the life and work of Alfred Kinsey (Dr. Sex, 1997) made more sense for you to write rather than a biography?

When I went back to school to earn an MFA at the age of 45, I had no idea what I would write but I quickly fell in love with the community and immediacy of theater and playwriting. I could write a scene, build a character, create a conflict one night and see actors put it on stage the next day. Theater is ultimately a collaborative art dependent upon the expertise of writer, actor, director, designer, etc. all working together and each adding their special spice to the creative stew. Non-playwrights (poets, novelists, etc.) sit alone at their computers, knock out a draft, send it to a publisher, and two years later, if they’re very lucky, get to see their work in print. They can only imagine the reaction of their readers sitting in another little room somewhere reading their work. But a playwright gets to go to the theater and sit with the audience to experience their writing together. Nothing is as powerful as seeing and hearing human bodies on the stage. Unlike a book, a theater piece invites the audience into a lived experience in the moment that can change the way they feel and think.

Your most recent play, “Locked,” delves into African American struggles with racism, identity, and family secrets. The overarching theme revolves around the past as prison and breaking free. Talk about the origins of this play, working alongside international artist Lorenzo Pace, and why “Locked” is important today?

At UTRGV I taught in the English Department and Lorenzo Pace taught in the Art Department. We were actually each in large departments in different Colleges within the same University, which had some 1,000 faculty. We might never have even run into each other but met by chance at an off-campus event. Lorenzo told me the amazing story of having in his possession the lock that bound the chains of his enslaved great grandfather transported from Africa to the American South. There is nothing more powerful than an object to anchor the story telling of a writer and Lorenzo had a whopper of an object in that rusted iron padlock.

That lock had a story to tell. For many years and over 12 drafts we crafted a script. We had amazing support from another colleague Trey Mikolasky in yet another department, Theater, who directed our table readings. The reality is that outside HBCUs theater departments tend to be overwhelming white. At UTPA the student body was 85% Latinx. We needed a majority Black cast for our play. Lorenzo and I ran around campus at lunch hour (he also visited a local Black church and I accosted Black people at the local supermarket) to recruit Black people to read these roles. You could write a play about the reactions we received. But we met a lot of great folks and recruited enough people to do readings but never a full production. So it’s incredible that the play is out in book form this year. America has been struggling with issues of race for 400 years. Now “Locked” can hopefully be part of that discussion.

You retired from teaching in 2018, but I know you’re still writing. What are you working on currently and where can readers find more information about you?

I love retirement! Of course I’m writing. It got me through the pandemic and shelter-in-place mandates. I only have a tiny work space with just enough room for a desk, computer, and three walls covered floor to ceiling in bookshelves. The other wall has multiple windows so I can see the garden I tend. My current project has the working title of Searching for The Thin Man: Nick Charles, Dashiell Hammett, and William Powell. It takes me from the hard-boiled detective fiction of Hammett to the films spun off from the novel to the Hollywood stars like Powell and Myrna Loy and Jean Harlow, to the studio system, to the producers’ conflicts with the Screenwriters Guild in the 1930s, right up to the 1950 HUAC hearings and Hammett’s imprisonment. The stories are filled with heroes and cads and surprise endings, so I am having a very good time in research and writing.

My son built me a website where you can learn more about my work and contact me.