I was introduced to Alistair McCartney’s latest novel The Disintegrations (University of Wisconsin Press) through our mutual writer friend Mark Gluth, and from page one I was grateful for the recommendation. True to its tagline, The Disintegrations is indeed “a haunting, obsessive exploration of death” that fascinatingly collapses the space between author and narrator. Here was a voice both uncannily familiar and decidedly unlike any I’d read, its own breed of ethereal friendliness, foggy acuteness, and distant confessional. It was, above all, the voice of a writer who deeply intrigued me, whom I yearned to hear more from.

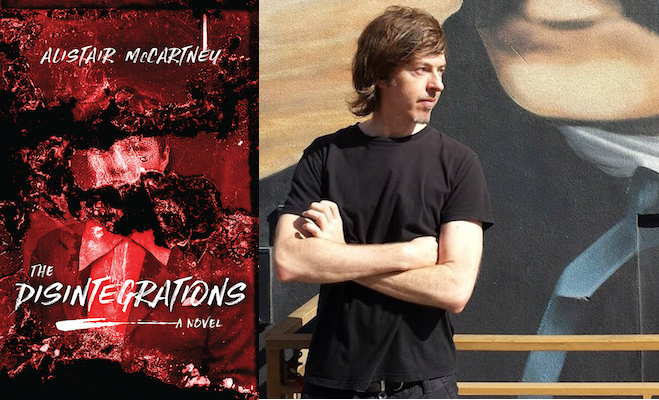

Alistair McCartney is the author of The End of the World Book, a finalist for the 2009 PEN USA Literary Award in Fiction. Originally from Perth, Western Australia, he now lives in Venice, California and teaches creative writing at Antioch University Los Angeles.

¤

MEGHAN LAMB: The Disintegrations is in some ways a very direct and honest work of non-fiction; the Alistair who narrates this book is very forthcoming, or at least convincingly performs a sense of directness. Of the same turn, the narration of the self-described novel is very slippery, addressed to a “you” figure who grows increasingly shadowy as The Disintegrations progresses. This “you” could simply be presumed as the reader, if not for their apparently mesmerizing effect on the narrator, and for the narrator’s understanding that this book could not exist without his imagination of “you.”

The novel begins with a provocative question: “Do you want to know something?” Do we, Alistair? Do I? Do you?

ALISTAIR MCCARTNEY: I love that you situate the book as caught between two genres, non-fiction and fiction. That’s the space where I’m forced to write from. The Disintegrations is a novel, a work of fiction, in the sense of Peter Handke’s notion of fiction as “the point of intersection between individual daily events” where “the most unarranged daily occurrences are only brought into a new order, where they suddenly look like fiction.” To be more accurate, my book is a récit, in Blanchot’s sense of this genre, a book that is as much about what cannot be told as what can, a book that is neither fiction nor non-fiction, but wedged in-between. A book that, as Lars Iyer writes of the récit, “marks the memory of the experience that the novel leaves behind in order to become a novel.”

And I love that you found the “directness” of my narrator convincing, because it is, as you indicate, most definitely a “performance.” The slipperiness of the narrative is for me, the condition of writing; as soon I begin to write, to represent anything, the ground of representation becomes unstable. This is especially the case in taking on the subject of death. I have the skeleton of a theory that the binary between life and death sets up the binary between the construction of non-fiction and fiction — in essence, the fact of death establishes the necessity of fiction. In regards to your question about the desire to know, I think we’re also caught in between: we want to know everything about death in a voyeuristic sense but we also don’t want to know, not really.

In many ways, this book is built around a sense of accumulation. The detritus of memory, of a lifetime — the crumbly, incorporeal stuff that gets left behind. As the narrator’s grandmother whispers to him in the beginning of the book, “Life is just a process of disintegration.”

In an apparent response to this whispering, the narrator begins to collect fragments of others’ lives (or, more to the point, he imagines their lives via fragments of their deaths). Do you see this book as a collection, as the satisfaction of an archival impulse? Or did it become something else?

That’s really interesting, and something I hadn’t considered: that it’s the grandmother’s words that starts the narrator collecting, remembering — she sparks the narrative. She’s like the witch at the end of Rimbaud’s “After the Flood,” “who will never tell us what she knows.” Similar to my writing from in-between genres, accumulation is crucial, the way plot is crucial to other writers. Accumulation replaces plot. Though a system of decomposition is probably more accurate to describe how this book “builds”; as you point out, all the narrator of The Disintegrations has to make sense of is the crumbly bits and megabytes of information and memory and anecdote that the dead leave behind. An archive is also a great generic description of my book (my first book, The End of the World Book, was an encyclopedia.) But I could never use the word “satisfaction” in relationship to that impulse: to archive the dead is a desire that can never be satisfied. Maybe this book is a cemetery, which is of course, a kind of archive. Maybe that’s the genre of this book.

Delving more into the subject of accumulation, which is one of my own obsessions: in The Disintegrations, there’s an ongoing examination of death as a kind of (auto)biographer of the ways death — in its finality — enables a eulogistic storytelling that wasn’t possible within a person’s lifetime. As the book’s narrator suggests, “I think what I’ve been telling you is a kind of eulogy…This could be a eulogy for anyone, for no one.”

Do you view The Disintegrations as a kind of autobiographical eulogy? Or is this book a kind of talisman against your own death, your own eulogy: a way of beating others to the punch, so to speak?

That’s fascinating, the notion of death as the writer of this book. Sorry to keep quoting from others, I’m sure I sound like some pretentious university professor, but it reminds me of Foucault’s notion that the singularity of the self — the true self — is only revealed when we die. Death creates a “black border” around an individual’s life and “gives it the style of its truth.” I was very interested in the different narratives we have to speak of the dead — obituary, elegy — the tension between death both flattening the self, but drawing out uniqueness, specificity. The notion of eulogy was really important as I wrote — in the book there are 13 stories of the dead, but I think of those stories as fictional eulogies, eulogies that would, to counter Foucault, never lay claim to speak the truth of the dead, perhaps pointing to the fact that even a standard eulogy is a kind of fiction.

As for the way this relates directly to me, the author, well, like my narrator, who of course is a totally fictional character, I’m really superstitious and would never want to talk about the concept of my own death. I’ll leave that to the book, which does explore the notion of the talisman. And the epigraph from The Book of Revelation I use also relates to this question, but I’ll let the reader interpret that.

One of many things I love about The Disintegrations is its singular manner of gesturing toward that most palpable yet ever-so-elusive of relationships: sex and death. Of a scene where the narrator momentarily departs a funeral for a tryst in the bathroom, he writes: “And it occurs to me now — it did not occur to me then — that we got the equation wrong, I mean in terms of sex and death. Maybe it’s sex that’s huge and death that’s small; maybe death will bring only a miniature oblivion, a modest shattering of the self compared to the mind-blowing, self-dissolving oblivion offered by a regular orgasm.”

I’m particularly drawn to the narrator’s self-presencing, this sly little interruption of futurity — “it did not occur to me then” — especially in light of the ways we learn this narrator’s life has changed with age. Do you feel this book can be experienced as a kind of compromise-orgasm, as an attempt to self-create while “self-dissolving”? Is writing a kind of gray space between the orgasm and death, the construction of a liminal death-y space? And if so, is the you the narrator addresses a kind of complicitous partner, a kind of lover?

Yeah, the nexus of sex and death is definitely one of the narrator’s main preoccupations, something I investigated even more in my first book. His obsessions are dialectical: he used to be fixated on sex, now the object of his fixation is death, resulting in the unavoidable sex-death synthesis. But it’s such an overdetermined relationship, just as death is the most overdetermined subject, and I was interested in this book in examining and questioning the relationship. That passage you quote is key to this line of questioning, which I think comes to a head in The Death Dream #1 chapter. I, or my narrator — here’s that slipperiness you referred to earlier — explores that space of sex and death as a mode of transgression, but increasingly he sees gaps in the equation and comes to see that if death can’t be overcome, then there’s nothing to transgress. In terms of tradition, I’ve definitely been raised or schooled on transgressive literature, but something I was exploring in this book is not knowing what it means to transgress. I’m glad you indicate narrative distance in the narrator’s observations about this material — perhaps he is developing after all, despite his doubts!

That notion of writing as a “compromise-orgasm” is fascinating. One of my favorite teachers, the great writer Kate Haake always declared “I write to disappear.” I do the same. And your positioning of writing and this thing we call “a book” as lodged somewhere in between orgasm and death is so cool. The Disintegrations took a long time to write, eight or nine years, and when I look back I feel like I’ve been in a liminal space all that time, that I kind of “blacked out” while I was writing.

The process was often less than orgasmic. That said, I did a radical re-write last year, where I really tore it up, rewired the structure and apparatus, and that was the only “stage” of the process that was “easy” and it was pretty blissful. My goal for my next book, which is probably delusional, is to let that pleasure in more.

I hope that jouissance is something my reader will also experience as they engage with The Disintegrations, a book in which there is more than one “I,” more than one “you.” In literature, as in sex and death, the self is both erased and multiplied. The ideal reader is always an accomplice and a lover. I hope we can “self-dissolve” together.

Alistair McCartney will be reading from and discussing The Disintegrations at Antioch University in Culver City on November 7, at 6:30 p.m. In New York he’ll read from it at Dixon Place Lounge, Saturday October 21, at 9:00 p.m.