Weng Pixin’s comics are tender. With acrylic paint, watercolors, and paper remnants, she creates vibrant and verdant landscapes: the rice fields of South China, the streets of La Plata Argentina, and more. In her first book Sweet Time, one story features a boy and a girl on a small boat floating down a river at night. They have a heady conversation about fate and pass a mysterious corpse burning on the wooded bank. “There is no full picture of the future,” the boy says. “Just dots on paper.” This, like many of Weng’s snapshots, is elusive and evocative, and lingers in the mind.

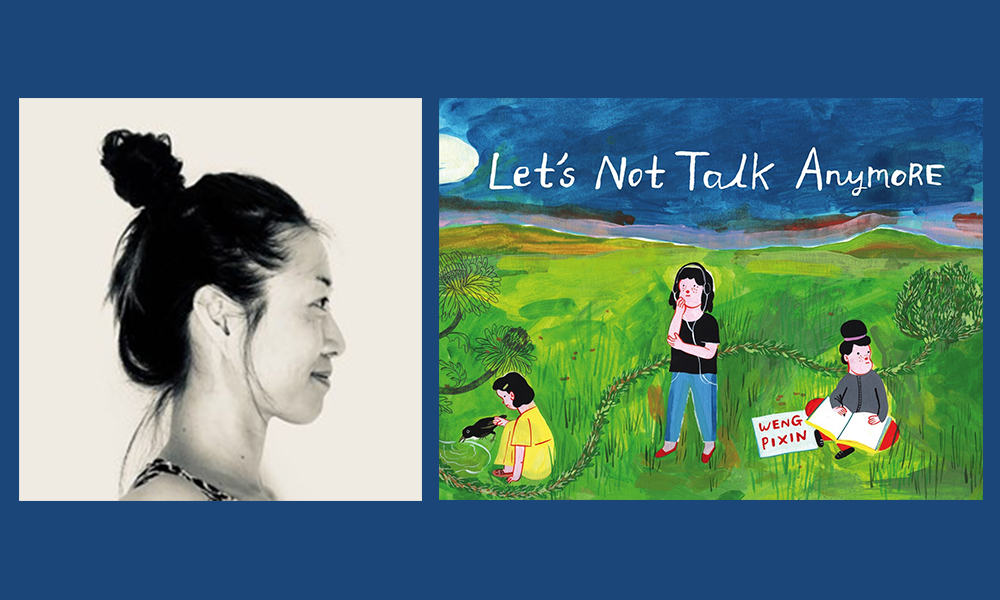

In her new book Let’s Not Talk Anymore, Weng threads together five generations of women from her own family, each at age fifteen. Fifteen is a moment of heightened vulnerability and helplessness for young people, as they experience tension between a longing for volition and dependence on their caregivers. For Weng’s characters, there is also a context of separation and trauma. Her great grandmother Kuān, for example, migrated away from her family in South China, and her grandmother Mèi was adopted by a neighbor to help with housework. Trauma repeats itself, but each consecutive time is experienced without understanding the preceding pain and similar struggles. In Let’s Not Talk Anymore, Weng’s paintings haunt with the aching silences that hang between generations.

I wrote to Weng to ask about tracing her family’s migration history, blending nonfiction and fiction, and her tools for making comics.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: In your previous book Sweet Time, you worked with different painting styles. In Let’s Not Talk Anymore, you settle upon a consistent method for a sustained five-generation story. What was the process for developing and deciding upon this aesthetic?

WENG PIXIN: For Sweet Time, it contains a selection of short comics (or short stories) made between 2008 and 2017. The varied style was because they were made at different points in my life, where the visual outcomes were also largely influenced by the situation or place I was in. Comics made in watercolors were likely due to my making the comic while at another person’s studio or space, so I tend to bring materials that were light and easy to clean up.

Other comics that were painted (with acrylic paints) were mostly made during art residencies abroad. The space provides a better working environment where there’s less worry of making a mess, so I would use the opportunity to paint more.

Some diaries featured in Sweet Time were made from paper remnants found at the residencies. Residencies tend to store leftover materials from previous visiting artists, which is always a great place to source for materials. For the paper remnants I found, I liked how the oddly shaped formats help turn the diaries into objects too, giving it a sense or reminder that the diaries can be held in your hand.

For Let’s Not Talk Anymore, the more consistent style (by comparison to Sweet Time) was probably because I looked at it as a single project. Although come to think of it, it would have been quite interesting to depict each character and her story in a completely different style! When I started work for Let’s Not Talk Anymore, the context was more that I had been making many short form comics for quite some time. Out of curiosity and perhaps as a personal challenge, I wanted to go through the process of sustaining a style to tell a longer-formed story, and to experience how that feels.

Drawn & Quarterly thrives at publishing books of all shapes and sizes. Can you speak a bit about why your books are horizontally oriented?

For Sweet Time, it might have been a more practical reason. Since the majority of the comic pieces were made in a landscape format, it became a case of needing to make the book horizontal.

Another reason might be, a tendency of mine to use horizontal formats because that, for me, seem to capture or hold feeling states a little more so than in a portrait, vertical manner. I find that I might make a story in portrait mode when I want to tell something specific. Whereas I might want to make a comic in landscape format if the story tends toward the more emotive side.

In one scene, your imaginary daughter Rita talks with you about the branching pattern on leaves and across the trees. Could you speak to how this relates to the way trauma (or love or joy) branches out across the book?

I’ve always been drawn to branching patterns in nature. It provides such a clear beautiful visual in marking the passage of time and of growth. The branching pattern in nature also gives you a clue to the natural object’s origins. A tributary of a river leads you to the water source. A leaf’s veins let you visually trace it to the leaf’s stem, to the branch, to the tree from which it came.

I think — in a slightly corny way — I wanted to include the scene with the “leaf” to serve as a visual metaphor. To describe what it is like to wonder about the figures along my matrilineal line.

Did your great-grandmother indeed carry a pet grasshopper as she migrated by boat from South China? How did you go about using whatever bits you do know from your family history and integrating them within invention?

Originally, I wasn’t intending to include my maternal great-grandmother and grandmother as characters in Let’s Not Talk Anymore. At that time, I felt it was because I knew nothing about them.

During the making of it, I was having a conversation with a friend. She was pregnant with her daughter, and we got to talking about our ancestors and of wondering about the lives of people along our family line. She encouraged me to look into including my great-grandmother and grandmother. Not despite, but especially because I knew nothing about them. As an art practice, I found that to be a very interesting proposition.

So, to fill in the gaps of not knowing about my maternal great-grandmother and grandmother, I relied on a mix of imagination as well as stories from my father. Mostly to get a sense of what life was like in the past. A lot of it came from research done over the computer.

One of the interesting results from the research was that I became curious about what farming life might have been like in China in the 1890s. I came across an article that talked about how children of farmers in the 1800s might keep crickets, grasshoppers, or other legged insects found in the fields as pets by tying a string around the insect’s legs. I found the detail so fascinating that I included my great-grandmother having a bug companion to help lighten a little of everything else in her story.

Why 15-year-olds, rather than, say, 5-year-olds, 30-year-olds, or 60-year-olds?

I was interested to explore how unmet needs and private tragedies can shape a person’s role as a caregiver, and specifically as a mother. This led to the decision to hone in on an age-range where the characters still relied on their caregivers for guidance and survival. But I didn’t want them to be too young because I wanted to show what the kind of work the characters do when their caregivers are not around. I landed upon adolescence: independent but not quite. Trying to gain control or make sense of their internal experiences, while still very vulnerable to the outside world. It was a kind of tension that I felt was suitable in the story I was trying to tell.

In one scene, your mother says to 15-year-old you, “If you don’t speak up, nobody will know what is wrong with you,” which feels both right and damning. Do you think there are ways your young characters could have been better helped to understand and articulate their own experiences and needs?

One of the things that I was interested to explore in Let’s Not Talk Anymore is a person’s capacity to attend to others’ emotional needs. How that can be informed by the way their own emotional needs had been attended to during their developing years. And how the possibility of unmet needs left as they are — unacknowledged, unconsidered, not reflected upon or worse, simply repressed — might create get a disruptive pattern of emotional unavailability. One that can get passed down from parent to child. For Let’s Not Talk Anymore, from mother to child. I chose mothers (rather than fathers) not only because of my personal experiences and observations of my mother, but also because of my interest in women’s lives of that particular period, where they led largely invisible and unrecorded existences.

But the short answer to your question would be yes, there are definitely tons of ways to help the young characters feel supported. However, considering the layers involved — poverty, gender discrimination, traditional cultural practices that discouraged communication or transparent discussions — it all (very sadly) culminates in a bad stew of dysfunctions. Just generally awful stuff with terrible consequences. But a great source of material for art!

Do you know what a piece is going to be when you first set out to create it or do you find the path along the way? What is the role of revision in your process?

I planned the rough idea for the book quite early on, in terms of the story I wanted to pursue for each character. Then I would find my path along the way. For example, I might be painting the pages of one character. Towards the end of the character’s segment, I would start sketching plans for the upcoming character’s segment. And the process would repeat itself.

In a way, this format was what made it helpful and possible, to include my great-grandmother and grandmother’s stories while I was half-way in the making of the book. I had been creating the story in a Tetris-like manner, where each character’s story is like a Tetris-block piece. It provided room and flexibility for me to move stories around for a different fit, without interrupting the overall goal.

The only revision was for certain pages, particularly ones that had been painted at the beginning of the process, when I was still figuring out the visual style of the comic. After painting many pages, I generally get a better sense and feel of what I would like the comic’s style to be like. So, I repainted a couple of the pages to give the book a better overall consistency.

What were the primary influences on the creation of Let’s Not Talk Anymore?

It’s a mix of personal experiences, such as memories of my mother, as well as impressions of her. It also includes my interest in listening to stories from my friends or people I meet, especially of stories related to the history or memories they have of their family. Let’s Not Talk Anymore also came about from my work as an art teacher with children, where I find myself observing children’s interaction with their parents or listening to the ways children try to describe or make sense of the actions and behaviors of adults around them.

What are your tools for making comics? Have they evolved or changed over time?

For Let’s Not Talk Anymore, I was using acrylic paint on thick watercolor paper. Cut papers for panels, and glue stick for pasting the text and panels.

My very first comic was made using markers on paper, back in 2006. Or dry mediums like pen or pencil on paper. It was during an artist residency in 2013 where I grew more confident in using paint for my comics. Works in Sweet Time do capture the experimental phase of my comic making, as I was trying assorted mediums or styles.

These days, I lean strongly towards using paint. I love working with the smudginess, the blobs and layers of colors to produce visuals for the stories I wish to share.

Has your relationship toward your storytelling with and among your family shifted over the course of writing Let’s Not Talk Anymore? If so, how?

I think the biggest shift is the relationship with my mother, as I grew a little more understanding to why she is the way she is.

Prior to Let’s Not Talk Anymore, the person she was, prior to becoming my mother, had always been an abstract in my mind. Putting myself in this space of imagining what her life might have been like, meant finding the visuals I would like to describe her life. Her surroundings. Her interactions. Turning what was once theoretical or abstract into something a bit more concrete. The guiding principle I worked with was: whatever the story may be, it must be highly probable and the details cannot be ridiculous, fantastical, or unrealistic. In finding the plausible, I was faced with questions such as: how would my grandmother talk to her? What’s the quality of those interactions? How was my mother when her father left the house without saying goodbye? What were her options like in general? Could she go outside whenever she wanted to? How did options limit or expand her personal goals and dreams?

In realizing she probably missed many opportunities due to many familial and societal factors, it became kind of ridiculous to stay mad at her. To react against a person who is herself very possibly still hurting and coping from past wounds.

Where do you find your community as an artist? Is it geographically based (in Singapore or elsewhere) or is it more remote?

I find my community in non-artist friends and artist-friends living in Singapore and outside of Singapore. In terms of my comic work, it has found more support overseas than in my country.

What are you working on next?

I’m currently working on a children’s comic book. It is based on a series of comic zines I had self-published called “Super Worm”. I started making Super Worm because there is this whole other side of me that loves the funny, odd, and weird. So I drew Super Worm when I am taking a break from other projects.

I am also working on a graphic novel that takes place within a single day, with an interest to capture a conversation between two friends. I want to explore how two individuals can recollect a shared dialogue differently. I was inspired by my friendships, especially with friends who are either a decade older or younger than me. The differences in age means having drastically different milestones and lens with which they make sense of their experiences, and in this case, how they each make sense of a shared conversation.