If you were a horror fan back in the late ‘90s or early aughts then you may be familiar with the UK distributor Redemption Films, which specializes in movies with titles like Nude For Satan, The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine, and The Rape of the Vampire. As a teenager, I was more interested in the Evil Deads and Re-Animators of the world and less in Redemption’s output; it wasn’t until recently that I gave them another look, and in so doing, discovered the hypnotic, strangely beautiful world of Jean Rollin.

Jean Rollin was a French filmmaker who came to prominence in the late ‘60s with his series of erotic vampire films. As described by Dave Kehr in the New York Times, Rollin was “a filmmaker drawn to the fantastique in a country that had a limited tradition of genre filmmaking as well as a proud tradition of Cartesian rationalism that discouraged explorations of the supernatural. What France did offer, however, was a thriving interest in eroticism.” There’s a lot to love about Rollin’s films, particularly the images that he creates, which are captivating in their strangeness: a woman in white, standing in the middle of a slaughterhouse, dead oxen dangling from meathooks around her; another woman crossing a stone bridge towards the camera, dressed in black and carrying an enormous scythe, looking for all the world like some feminized incarnation of death. Technically rough around the edges, his films nevertheless project a personal vision and aesthetic every bit as distinct as Dario Argento and Mario Bava.

Despite his early prolific output, Rollin remain relatively unknown in the states. Spectacular Optical Publication — the brainchild of Kier-La Janisse, whose book House of Psychotic Women is arguably the most groundbreaking work on genre cinema of the last 25 years — hopes to change that with their forthcoming book Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin, which collects essays by women critics and scholars and is edited by Samm Deighan, who is also an associate editor of Diabolique Magazine. The company is currently running an Indiegogo campaign to help support the publication, which “closely examines Rollin’s core themes: his focus on overwhelmingly female protagonists, his use of horror genre and exploitation tropes, his reinterpretations of the fairy tale and fantastique, the influence of crime serials, Gothic literature and the occult, as well as much more.”

I had a chance to speak with four of the contributing writers — Lisa Cunningham, Marcelline Block, Marcelle Perks, and Alexandra Heller-Nicholas — about Rollin’s work, and their connection to it.

¤

IAN MACALLISTER-MCDONALD: How would you describe Jean Rollin’s work to someone who’s never seen one of his films before? With so many wonderful genre filmmakers out there to explore, what makes his work particularly enticing or interesting?

ALEXANDRA HELLER-NICHOLAS: You know that beautiful faded flocked velvet wallpaper you see in old black and white movies? Imagine that as a movie, but sexier and more gory.

MARCELLE PERKS: Rollin films like a set photographer, as if he wanted to create as many evocative images as possible. In fact, he was personally influenced by painters such as Magritte and the Surrealism movement. He combines erotic and gothic elements in unsettling ways and is marvelous at depicting the female form.

LISA CUNNINGHAM: Rollin makes visually beautiful, unpretentious films. His handling of women and their lives, particularly, is done with consideration and nuance, if not delicacy (which would be to its detriment, anyway). I find his emotionality a wonderfully unique experience in film-watching.

MARCELINNE BLOCK: Rollin’s films are personal meditations upon life, love, and death, situated within the context of the supernatural and the fantastique. Moreover, as Rollin’s films take inspiration from and are influenced by iconic French authors and poets — including Tristan Corbière, Gaston Leroux, and Jules Verne — they demonstrate a strong literary component and heritage. Rollin has often been called a poet of the cinema whose fantastique films express a melancholy, romantic aesthetic imbued with Surrealism and/or Dadaism.

IAN MACALLISTER-MCDONALD: How did you first discover Rollin’s work and can you remember your immediate reaction? Was he a filmmaker that grabbed you immediately or did his work grow on you slowly over time?

ALEXANDRA HELLER-NICHOLAS: In Australia, during the 1980s and 1990s in particular, the television channel SBS specialized in international cinema, with Friday and Saturday nights really dedicated to cult film. So much of my cinema literacy stemmed from the half-remembered traces of films seen there, in whole or just fleeting moments: I remember being both repulsed and magnetically drawn to Rollin’s La Morte Vivante when they played it, and I kept turning the channel to far more vanilla fare, but couldn’t resist flicking back. That pull-and-push has always for me been the allure of Rollin’s films, I think it’s the internal dynamic that runs through so many of the films themselves.

MARCELLE PERKS: The first film I saw was The Living Dead Girl. It breaks the rules of the genre because the lead character still retains traces of her human consciousness and thus blurs the boundaries between victim/monster. As he so often plays with the rules, audiences may find themselves confused, especially if they have seen too many standard horror films. The trick is to watch more and grow accustomed to a different sensibility.

IAN MACALLISTER-MCDONALD: Jean Rollin seems, to me, to be a filmmaker whose work walks a fine line between empowerment and exploitation. (Obviously feel free to disagree with that interpretation.) As such, a book devoted to his work, written entirely by female scholars, feels both appropriate and intriguing. Could you speak a bit about how his films touch upon gender and what you find interesting about Rollin’s treatment of women in his films?

ALEXANDRA HELLER-NICHOLAS: Traditional approaches to gender politics in horror cinema have always tended to default far too unquestioningly towards the woman-as-object model, which — as emphatically (often overtly to the point of comically) sensual as his many women characters are — I think that approach really undermines just how hugely proactive these women are, not just as characters, but as performers. Actors like Marina Pierro, Franca Maï, Mireille Dargent — so many of the women he worked with could claim a degree of “authorship” over these movies in a sense (whatever that means), as I simply couldn’t imagine these films working without them. And as skeptical as I am about the ideological utility of the Bechdel Test outside a cute gimmick to up awareness about gender issues in screen culture (I’ve vented spleen about that here), if that is something important to your idea of progressive/regressive distinctions, it’s worth noting that his films pass with flying colors.

MARCELLE PERKS: My article tackles the topic by examining his use of the “final girl.” What’s interesting about Rollin female leads is the degree of control they have. They can engage in sexual activity or not, and are not punished for it as in conservative horror films. Very often they depict unusual obsessions which are sympathetically handled. As well as offering a different type of final girl, Rollin’s killers are also not depicted in binary terms of good versus evil. In these films, his use of the themes of infection, and both physical and mental illness, often provides an explanation for the behaviour of his antagonists, who sometimes regret their actions but are powerless to stop themselves. The final girls in these films are all unexpectedly violent; Rollin provides an alternative to the formulaic tropes favoured by his American counterparts.

LISA CUNNINGHAM: I personally find his treatment of “women in his films” (if that is, indeed, a single category which can be addressed) to be nuanced and emotionally-focused. There is a tendency whenever women are sexual in film to call it “exploitative,” but I consider a treatment of femininity which takes into account sexuality and its complexity to be more honest regarding certain women’s experiences.

MARCELLINE BLOCK: The representation of female characters in Jean Rollin’s films gives rise to a rich field of inquiry, discussion, and debate. Women are featured throughout Rollin’s filmography in a complex variety and network of roles, positions, and performances, functioning as elusive or unattainable love objects, as agents and/or victims of manipulation, sadomasochism, and violence, and are given to self-destructive impulses. Starting from his very first film, Les Amours jaunes, women have had a significant presence in Rollin’s filmography. This short black and white film, which takes its title from 19th century French poet Tristan Corbière’s single book of poetry published during his brief lifetime, is set to the verses of Corbière’s poems “Aurora” and “Le poète contumace” (“Poet by Default”). The poet-protagonist of Corbière’s “Le poète contumace” addresses an elusive woman who is his unattainable love object. Lost or doomed love is a recurring element throughout Corbière’s poetry as well as Rollin’s filmography; indeed, Corbière was a major influence upon Rollin and his words and poems are featured in Rollin’s films.

IAN MACALLISTER-MCDONALD: Can each of you talk about your specific essay in the book? What is your background and how did you settle on your subject? Did re-watching Rollin’s work through that lens teach you anything new about his films?

ALEXANDRA HELLER-NICHOLAS: I’d been a fan of Rollin for years but it was only when writing my first book, Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study, that I discovered he did what could loosely fall under the “rape-revenge” trope umbrella in his 1974 film Les Démoniaques. I loathe the word “problematic” for a bunch of reasons, but I think Rollin’s depiction and deployment of sexual violence would certainly fall under that category for a lot of us, as heavily and unapologetically eroticized as it is (his first film as director was, of course, Le Viol du Vampire, or The Rape of the Vampire, in 1968). But I think it’s a huge mistake to dismiss Les Démoniaques, as gender politics play a major role in the film. What I find really fascinating about it is how it configures the supernatural powers bestowed upon its rape-avenging women protagonists in what is ultimately an ambivalent way: there’s no magic cure, you don’t seek revenge, get it, and bam, everything is solved. It’s certainly a challenging film, but in my mind a really important one that is often overlooked in both rape-revenge film history more generally and in terms of Rollin’s own filmography.

MARCELLE PERKS: A friend of mine bought me Night of the Hunted, which initially I couldn’t watch all the way through. And yet the film haunted me. When I was asked to write for the book I wanted to write about the lesser known films and examine his work over different genres. The unusual way in which he depicts erotic moments (that are sometimes inappropriate) and allows his female leads a greater-than-usual degree of independence was compelling.

LISA CUNNINGHAM: When I saw Les Paumees, which isthe focus of my essay, for the first time years ago, I didn’t have as large a frame of reference in terms of filmic dialogue and cinematic technique as now. I saw the girls then as weak or foolish for not simply compromising their way out of their positions. Rollin’s point, I realized this time, was largely about their uncompromising individuality being both an enviable trait and the thing that makes them monstrous to society. After a few more years of being a woman, that is, I empathized much more with the stances of his female characters.

MARCELLINE BLOCK: My background is primarily in French history, literature and film. Therefore, when I was invited to submit an abstract for the book, I proposed to write about the significance of French “poète maudit” Tristan Corbière (1845-1875) for Rollin as well as the influence upon and presence of Corbière’s poetic works in Rollin’s films. My chapter considers Rollin’s first film, the short Les Amours jaunes, which takes its title from Corbière’s eponymous 1873 collection of poems, his only published book of poetry during his lifetime. It also considers Rollin’s later feature film, La Rose de fer, in light of Corbière’s influence. Corbière lengthy poem “Le poète contumace” — which many critics consider one of his best, if not his best, works of poetry — is recited in both Rollin films, and Corbière’s poem “Aurora” is also recited in Les Amours jaunes.

Watching and re-watching Rollin’s works through the lens of Corbière was enlightening, as it truly demonstrated Rollin’s literary heritage, which draws upon texts by iconic French writers, recalling, for me, other examples of 19th as well as 20th century French literature and poetry, including Victor Hugo’s “Oceano Nox,” George Sand’s La Mare au diable, and Paul Valéry’s Le cimetière marin, as well as Paul Verlaine’s discussion of Corbière as one of his three original Poètes maudits, all of which I discuss in my chapter in terms of how they relate to Corbière and Rollin.

My first edited volume, Situating the Feminist Gaze and Spectatorship in Postwar Cinema, includes chapters written by film scholars that consider horror and thriller films about women from a feminist perspective. I first encountered works of feminist horror scholarship, such as Carol Clover’s Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film and Barbara Creed’s The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, when writing and editing this book.

IAN MACALLISTER-MCDONALD: What’s your favorite scene, moment, image, or line of dialogue from a Jean Rollin film, and why? Is it somehow representative of larger themes, ideas, or aesthetic trends in his work?

ALEXANDRA HELLER-NICHOLAS: This is such a great question because I honestly believe what makes Rollin’s films so magical and audacious is that they function more like dreams, in the sense that its fragments float to the surface more readily than plot or character, quite unlike the majority of other filmmakers both then and now. Certainly the most emblematic — and devastatingly beautiful — image is the brief shot of Isolde the vampire climbing spider-like out of a grandfather clock in Le Frisson des Vampires . It’s such a potent, powerful, and deeply poetic image: the idea of the feminine not only emerging from time, but being a tangible, material part of it, leaping literally forward to stake a claim, to have her fleshy, intoxicating presence made known. If there’s anything that sums up the power of Rollins films (in regards to gender as much as aesthetics), it’s this.

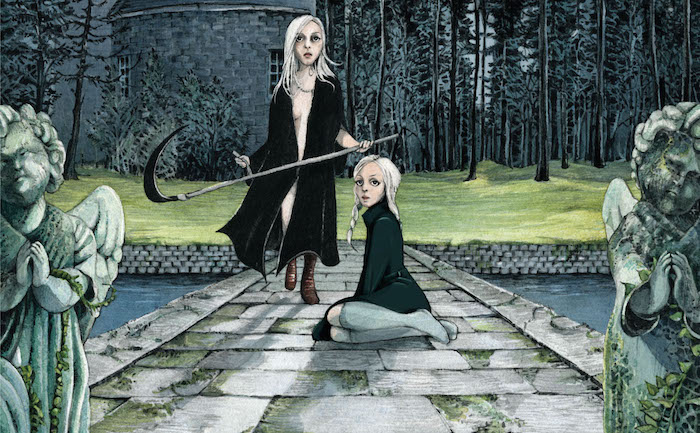

MARCELLE PERKS: The image of Brigitte Lahaie with her scythe in Fascination is just visually stunning. The traditional image of death revisited in the form of a beautiful woman with a sadistic smile on her face, daring you to look at her scantily clad form before she kills you…

MARCELLINE BLOCK: I would say the opening moments of Rollin’s La rose de fer, including that of The Girl (Françoise Pascal) walking along the beach at Pourville-lès-Dieppe on the coast of Normandy — Rollin’s favorite filming location, which appears throughout his filmography, starting with his first short film Les Amours jaunes (1 and finding the titular iron rose that has washed up on the beach and caressing it before throwing it back into the water. This scene is representative of the important place that this beach holds in Rollin’s life as well as throughout his oeuvre, which further links him to 19th century French poète maudit Tristan Corbière. Central to Corbière’s poetic oeuvre is the sea and the coastline of his native Brittany.

Another favorite image is the subsequent opening title sequence of La rose de fer, during which The Girl (Françoise Pascal) and The Boy (played by Hughes Quester) tightly embrace each other while standing on the platform of an abandoned train car, which is shrouded in mist. Moreover, the scene is set to mournful, non-diegetic instrumental music (in a minor key), which, along with the mist surrounding the train, further imbues this romantic moment with an eerie, tragic, foreboding, and ominous quality. This sequence’s combined elements speak to the larger themes of haunting, otherworldly beauty and sadness as well as doomed love and melancholia that characterize much of Rollin’s filmography.