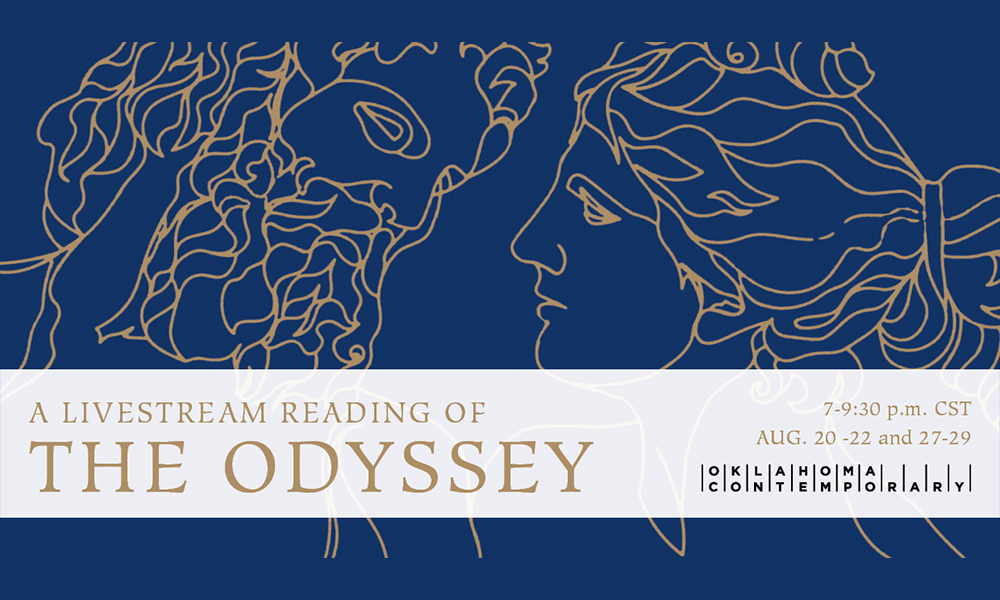

In a six-day livestream the Oklahoma Contemporary and the Kirkpatrick Foundation have brought together 24 musicians, actors, artists, and public officials to read Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey. The oral presentation of Homer’s epic poem is a digital recreation of collective listening and considers what it means to find home in an era in which the world is home-bound.

In Wilson’s own words, “The Odyssey emerged from an oral folk poetry tradition in archaic Greece, and it’s a joy to see the poem’s performative roots being honored in 21st century fashion with this virtual live performance.”

Bethany Joy Collins, one of the featured marathon readers, is a Chicago-based artist. Collins uses language as both the material and subject matter of her practice, not only engaging with the meaning in and of the texts that she studies — such as historical newspaper publications, Webster’s New World Dictionary, The Southern Review, and patriotic lyrics — but also with the duality of this system, its necessity, failures and also its physicality through repetition, erasure and play. A particular text she has been working with is The Odyssey and its various translations, including Emily Wilson’s.

¤

LARA SCHOORL: What is your relationship to The Odyssey; how did you become part of this marathon reading?

BETHANY JOY COLLINS: Right after the 2016 presidential election, I added a lot of post-apocalyptic literature to my reading list. I wanted to know how different people named or described the end of the world, so I could have the language of that moment for myself. Eventually, I realized that post-apocalyptic literature was not exactly the work that I needed and came across Emily Wilson’s beautifully efficient translation of The Odyssey. This ancient text of exile and homecoming and strangeness among intimates felt right. In my work, I’m comparing translations specifically from Book 13 of The Odyssey which tells of Odysseus’ homecoming. When after 20 years away, a decade spent searching for his homeland, he finally stands on the shoreline of his own country, and does not recognize the place. Which felt like a way to describe that post-election moment for me, when the country felt somehow familiar and estranging at the same time.

You are right, The Odyssey is a story of being lost, not only literally in losing one’s way from A to B but also personally. Perhaps even more so than in 2016, the feeling of being lost is omnipresent now. I am thinking of translation now as also a process of losing. In translation, some may say, a part of the original is lost while trying to maintain it or be in proximity to it. In a way it seems as though we are going to a similar process; getting lost in our current world as a result of the upcoming presidential election, a pandemic and an ongoing fight for social justice in order to imagine it anew.

As the next election draws near, I’m looking more at utopian literature than post-apocalyptic, and thinking about the imaginative possibility of a different world. I just finished reading Toni Morrison’s Paradise where every garden is an idea of utopia — one among many. The idea of utopia, especially presented by Black authors, Black writers, is never perfect. By definition, utopia requires that someone will always be included and excluded. Imagining a new world also feels, not hopeful, but like a brave move or a necessary tactic to consider what else is possible for us. It is not about hope — as I’m often asked in interviews — but about imagining that something else might be feasible.

Your work around The Odyssey and other text is mostly visual, or its presentation is. What do you think about this reading as an oral presentation of this text in relation to your own practice?

One of the core tenets of my practice is adopting texts that feel unwieldy or problematic and then enacting a labor intensive process to deconstruct and gain control over it. My Noise series, for example, started with problematic texts about race and identity and then morphed into love lyrics from patriotic hymns. I would write these problem texts again and again until my hand hurt and only then I knew that I could leave, that I could walk away from that language. These processes of pain make the text manifest in the body and eventually result in a kind of mastery over the text. The body transforms language. Reading aloud is much like song — we are entering the text and language is transformed through the body, but without pain.

I grew up in a Presbyterian church in Montgomery, Alabama and used to participate in their 72-hour Bible readings. You would sign up for your hour, noon, or 3 a.m. and read from the pulpit, hoping someone would relieve you at 4 a.m. Whether sacred text or The Odyssey, what I find beautiful about this shared reading, is the idea that a text is considered worthy of being read back into the world even if no one is there to listen. That feels much like our democracy right now.

I think it is interesting to have this endurance reading now and bring an ancient text into our world. There is a beginning and end to these readings, but that does not matter so much. Rather, it reminds me of the beginning of Wilson’s translation: “Now goddess, child of Zeus, / tell the old story for our modern times. / Find the beginning.”