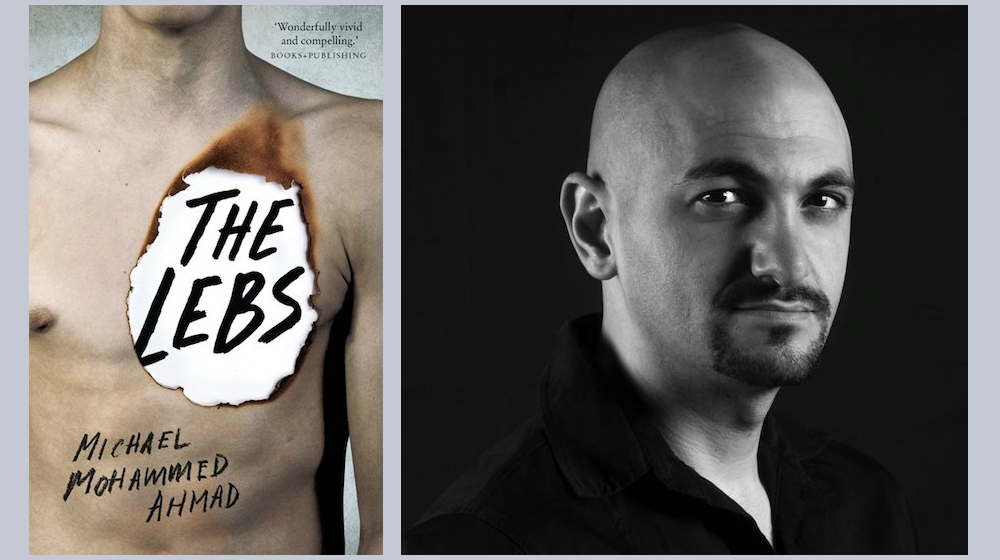

With an interest in identity, place, and relationships, Michael Mohammed Ahmad is the founder and director of Sweatshop, a literacy project devoted to creative writing by culturally and linguistically diverse artists in Western Sydney. His debut novel, The Tribe (2015), won a Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelists of the Year Award. We caught up to chat about his recently-released follow up, The Lebs.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: What did you read growing up? And how does this fit in with your family background and experiences?

MICHAEL MOHAMMED AHMAD: I think it’s assumed that all writers had access to literature as children. My reality as a second generation Arab-Australian Muslim was that my entire family was illiterate. My grandparents, parents, and dozens of aunts and uncles came to Australia from Lebanon in 1970 with no money and no education — reading was a privilege they could not indulge. My love for books did not come from the literature that surrounded me; it came from the absence of literature, the fact that I was constantly looking for things to read in a house with no bookshelves. I don’t know where that feeling comes from, why some children have an innate desire to read, but the Qur’an says that Allah taught humankind that which we did not know by means of the pen — so maybe it’s just the way we are created.

If reading comes from somewhere innate, what about writing? Where did your interest in writing come from?

I don’t know exactly where my interest in writing came from but the other day I found a box of my old short stories, about 30 of them in total, and they were written when I was 14 years old. They were all about a handsome, charming, White-passing teenage boy with incredible intelligence and wit, and super-model women who were deeply in love with him… Yeah, I’m pretty sure I became a writer because I was an ugly self-hating kid who couldn’t get a girlfriend.

I like the idea that we are formed by absence and not only desire. How did this experience dovetail with an understanding of place, identity, and family in your first novel The Tribe? How did that fit in with your education?

There were certainly aspects of my identity as an Arab-Australian Muslim man which propelled me to write The Tribe. In the West, so much is said about us and for us, but little is said by us. I considered it a political act of self-determination to reclaim representations of Arabs and Muslims that had been hijacked by White people. However, I don’t ever think that the social and political importance of my story should overshadow the fact that I had 10 years of university education in creative writing. This includes four years completing an arts degree, another two years completing my honors degree, and another four years completing my PhD. It’s extremely insulting to our education as writers when some wannabe wakes up one day and decides to start writing a novel simply because they believe they’ve had an interesting life. I argue that you can’t get away with this kind of attitude in any other industry. If you decided one morning to just call yourself a plumber without study and practice, it won’t be long before you’re covered in shit; if one afternoon you decided to call yourself a GP and started handing out pills without a degree in medicine, the police won’t be very far from your doorstep; and if you got into a boxing ring one night without rigorous training, you’ll find yourself on the canvas in a few short seconds. I always emphasize to my students and fellow writers the importance of engaging in creative writing as a skill, which, in addition to having something significant and unique to say, requires serious education and research.

Education is also a theme in both your books. What is the direction you took following The Tribe with your next book The Lebs? And can you tell us what the narrative of the book is?

The Tribe was the first novel I wrote in a trilogy I am developing on Arab-Australian Muslim male identity. It is told from the perspective of Bani Adam, a fictional version of myself at ages seven, nine, and 11. The book details Bani’s experiences within a large Lebanese-Australian family. The Lebs follows on as a direct sequel to The Tribe, only this time the stakes are much higher. Bani is now a teenager at 14, 16, and 19 years old throughout the novel and he is dealing with many of the usual issues teenage boys face — coming to terms with his gender, sexuality, race, and class whilst also trying to obtain an education. This is complicated for any teenager, and any person in general. However, for a Leb growing up in Western Sydney between the years 1998 and 2005, what I am describing is a war zone — Bani’s high school is surrounded by barbed wires and cameras, and within the school he and his friends are regularly caught up in severe acts of violence, misogyny, racism, homophobia, and religious extremism. On the outside of the school, Bani faces a political climate that is dominated by news headlines in Australia and around the world which have demonized and homogenized young men like himself as criminals, gangsters, sexual predators, and terrorist suspects.

At the level of style, your attention to the colloquial, the vernacular, the everyday, especially in dialogue, is one of the things that is particularly impressive in the book. I am not alone in noticing this (see Martin Shaw in his review in Books + Publishing), but can you tell us about the formation of your ear? In what way does it come from lived experience and what are some of the challenges of putting this into a novel?

Everything I write comes from lived experience. This doesn’t mean that everything I write is fact, but rather that everything I write is true — true to my identity. I think a lot of wannabe writers try and sound “literary,” they want to emulate the written tradition of the dead White male — Shakespeare, Joyce, Faulkner, Hemingway, Dostoyevsky… From a literary point of view this doesn’t make sense to me. Shakespeare and Joyce and Faulkner and Hemmingway and Dostoyevsky weren’t trying to sound literary, they were just trying to sound like themselves — and that’s what made their work literary. As a storyteller, I never doubt the uniqueness of my reality, I know that the voice of the Lebs and the voice of Western Sydney is remarkable. We all hear our reality. A good ear is about listening to our reality.

What have the community responses, multiple and varied as they are, been to the book? Have people recognised themselves as characters and, if so, how have you negotiated this relationship between fiction and reality?

I believe that in literature there is no distinction between fiction and reality. The Autobiography of Malcolm X is a fiction because it is just one version of the way Malcolm understood his own life within the context of a very particular moment in his life, and Star Wars is a reality because it reflects the way George Lucas sees, imagines, and understands different genders, classes, sexualities, cultures, races, and places from the limited point of view of a rich straight White man.

There are many people who have read The Lebs only to search for themselves in the text. When they find what they are looking for, they verbally and physically attack me, they threaten me, they slander me and they boycott me. I always tell them the same thing when this happens, “You don’t know how to read.”

I want to turn now to situate The Lebs in a wider artistic practice, which includes your involvement with Sweatshop. What is Sweatshop and how does it influence your personal creative output?

Sweatshop is a literacy movement I founded in 2012 which is devoted to empowering culturally diverse communities in Western Sydney through reading, writing, and critical thinking. The philosophies of Sweatshop are built on the ideas of African-American writer, feminist, and social activist bell hooks, who argues that “all steps towards freedom and justice in any culture are always dependent on mass-based literacy movements because degrees of literacy determine how we see what we see.”

I cannot separate my own work as a creative writer from the broader literacy movement that is Sweatshop. As a young person of color growing up in the western suburbs of Sydney, I became incredibly fatigued and infuriated by the way we were constantly and viciously misrepresented or underrepresented in mainstream media, literature, film, television, and politics. I established Sweatshop as a window for me and people like me to push up against our own sense of marginalization.

Can you reflect on the question of being an emerging writer in the wider Australian literary landscape? What are some of the challenges and hopes facing us?

The problem is that I’m not really treated like an “Australian writer” in the Australian literary landscape — because for many readers in this country and around the world, “Australian” still means “White.” Our challenge as writers should be to redefine what we mean by “Australian literature” and more broadly, what we mean by “Australian.” We don’t need to hope. We just need to read.

If we just need to read, whom should we be reading from a new generation of writers?

Read Ellen van Neerven, Claire G. Coleman, Julie Koh, Peter Polites, Maxine Beneba Clarke, Maryam Azam, Omar Sakr, and Omar Musa (yes, there can be more than one Omar in Australian literature). Also keep an eye out for the next generation of Australian writers, Stephen Pham, Monikka Eliah, Winnie Dunn, Phoebe Grainer, and Shirley Le. And please don’t buy any more books written by White people about Indigenous people, colored people, and boat people. Buy our books and let us speak for ourselves.