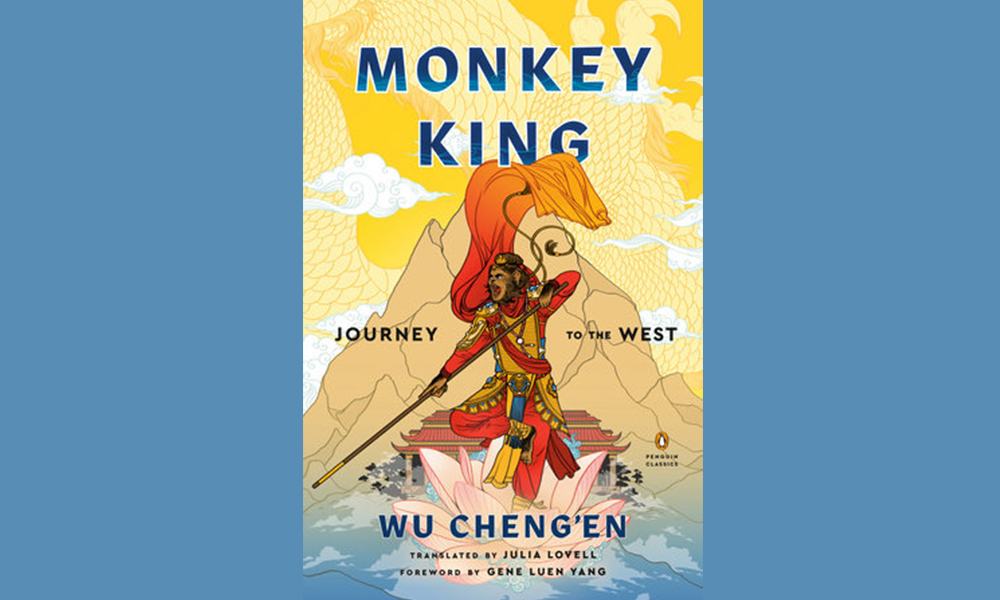

UCI professor and LARB advising editor for China, Jeffrey Wasserstrom, talks with award-winning historian and translator Julia Lovell of Birkbeck College, University of London, about her most recent project: a new, abridged translation of the beloved Chinese novel, Journey to the West.

¤

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: When did you first read or become interested in Journey to the West? And what did you find attractive about the book?

JULIA LOVELL: Journey to the West was, to my knowledge, my first contact with East Asian culture. I grew up in a remote part of provincial England in the 1980s — a time and place where China seemed to exist on another planet and felt so distant from my ordinary life. But on Saturday mornings, I would sit in front of the TV mesmerized by a show called Monkey. Only years later did I realize that the program was a Japanese adaptation of Journey to the West. With Monkey, even though the production values were low and the dubbing was clumsy, the characters and situations were so hilariously eccentric that it became a cult cultural phenomenon for me and for many of my generation in the UK. It was only much later, when I actually read the novel Journey to the West (first in the Arthur Waley abridged translation, then in Anthony Yu’s full version as a university student of Chinese) that I began to appreciate the richness and complexity of the novel — its spiritual elements as well as everything it tells us about Chinese society and religion. But the aspects that had so appealed to me as a child still held: the extraordinary fantasy sequences, the rebellious irreverence of the character Monkey, the out-there monsters and demons, and the Kung Fu fighting sessions. I actually rediscovered that old Japanese TV show with my teenage son last year, and I was struck by how he, too, was immediately entranced and entertained by it. On social media, he even uses the face of the Monkey character as his avatar, and he includes as his tagline a part of the show’s opening credits, “the nature of Monkey was irrepressible,” which is a succinct summary of the character Sun Wukong. So, it’s something which appeals to millennials as well as those who grew up in the 1980s.

I can’t resist a digression here because as I was listening to you talk, I was reminded of what was probably the first part of Chinese culture that I really engaged with — growing up in a different decade in a different part of the world — that was also a television show. The show was Kung Fu, which was set on the American West and featured a figure who talked about things like traditional Chinese philosophies. I was fascinated by this. Curiously, the show has come back into the news lately in a way that links up with a figure who is interesting to me in my research. The program has become controversial now because the great martial arts artist and actor Bruce Lee wanted to play the lead role in Kung Fu, but instead the role went to David Carradine, who is white, so the show is now often discussed in terms of miscasting and cultural appropriation. Recently, due to my own research, I grew very interested in Bruce Lee because the late actor was serving as an inspiration for some of the Hong Kong protesters, the group I wrote about in my most recent book. So, it is strange how, through our careers, some of the things that were part of our early engagement with China can then become part of our later career as well.

It underscores the unpredictability of the channels by which we make contact with different cultures, as you say, often sometimes in unsatisfactory or problematic ways. But these trajectories can be very unpredictable.

Yes. And I think it was also really interesting that it was a Japanese rendition of Journey to the West that drew your attention to it. Because in a way, that’s a nice story of multiple cultures mixing together in itself, as this story was very popular and very well-known across East Asia.

Exactly. For one thing, I think the mythology within Journey to the West absolutely draws on elements beyond the geographic entity of China. There are theories that the character of Monkey is based on parts of Indian mythology, for example, and the story has a huge currency and influence in Japan as well. So the journey itself of Journey to the West, through Japan, and then into the sitting rooms of the provincial UK in the 1980s, is a really nice transnational story.

Speaking of transnational stories, this translation you’ve taken on is your first book after your important look at the global influence of Mao Zedong. I know that Mao sometimes said that Journey to the West was a favorite book of his. Was his interest in the book one of the things that spurred you to take on this translation project at this moment in your career?

Certainly, this element became an important link between the two projects, although I ended up taking on the two projects at roughly the same time, in 2012. But the link that you mentioned really helped propel these two projects forward in parallel. Because Mao had a deep appreciation of the book Journey to the West, and of its hero, Sun Wukong “the Monkey King,” the book had a very definite resurgence after the Communist victory in 1949. In the introduction for my translation, I talk about how Journey to the West, which is a novel about shape-shifting, has itself shape-shifted in different political and social contexts.

And this attribute of the novel is particularly striking under Mao. Between the 1950s and the 1960s, Mao and his savvy political and cultural lieutenant Zhou Enlai used the parts of the novel that suited their own agendas. They sponsored adaptations, they wrote poems, they promoted the book in a way that made it all about Monkey’s rebellion against the heavenly establishment. In the communist scheme of things, Monkey stood for the peasant masses while the Jade Emperor and the heavenly authorities stood for the bullying upper classes that Mao saw himself overturning. Mao and Zhou thus made the book all about this struggle, rather than about the tempering of Monkey’s wild nature through the trials and tribulations of the pilgrimage to the West, which is, of course, an absolutely huge part of the novel as well. And to Mao, Monkey’s havoc-wreaking instincts were a lifelong inspiration to the point that Mao publicly identified himself with Sun Wukong in the 1960s to justify, for example, the overthrowing of the party establishment in the Cultural Revolution.

Fascinating, and this selective use of Journey to the West happened just when Dream of the Red Chamber, another wildly popular late imperial Chinese novel was being criticized. You’ve already brought up the theme of irreverence and revolution within Journey to the West that was accentuated by Mao and Zhou. In Dream of the Red Chamber, the characters stay put basically in one locale, though there are fantasy elements in it, and it can be seen more as reinforcing rather than challenging conventional ideas. In Journey to the West, travel is central, as well as connection to other parts of the world. Do you think it makes sense to contrast the theme of travel between these two books? Or do you see important similarities between the books that I’ve missed?

This kind of comparing and contrasting is thought-provoking. I personally am extremely in favor of using literature, amongst other things, as a kind of primary source for understanding aspects of Chinese history or society. In my reading — I’m not an expert on Dream of the Red Chamber, of course — but in my reading of it, a lot of it seems to be about worldly, material aspects of life in the Chinese Empire at the moment in which it’s set. By contrast, so much of Journey to the West is fantastical, escapist, and, in some ways, deliberately exoticizing. But I’d also complicate the characterization of Journey to the West here. As you say, it is about disorder, disobedience, and rebellion by Monkey and others; but it’s also about the tempering of Monkey by religious discipline, so that he becomes a better creature, a better being. Although it’s worth pointing out that this process of tempering is never complete, it’s only ever partial in the case of Sun Wukong.

On the subject of travel, you could also argue that, although Journey to the West seems to be about travel out of China, across Tibet, and into India, this is maybe only a spiritual rather than an actual physical journey. When you actually look hard at the narrative of the journey, a few things stick out: the landscape through which the pilgrims travel changes actually very little and the pilgrims never seem to be struggling with languages — so maybe everyone’s speaking Chinese all the time. The Chinese religious hierarchies that hold sway in the beginning of the journey continue to hold sway however far the pilgrims travel out of China. On the face of it, it seems to be a book about a physical journey, but whether that journey is indeed physical or actually moral and spiritual is not actually completely clear. The book is also full of empirical insights, if you like, into Chinese attitudes about spirituality in the afterlife, especially about the close resemblance between mortal and spiritual realms. I’d argue there’s plenty of social, historical, and cultural illumination to the book, in addition to the far-fetched fantasy sequences.

In terms of your question about what to pair the novel with, or what would be a good comparative text, I think it would be really fun to look in detail at the impact of the style and structure of Journey to the West on contemporary mainland Chinese writers, such as Mo Yan, the 2012 Nobel literature laureate. You hear so much about the influence of books in European languages, including Latin American magical realism on Mo Yan’s generation (writers born in the 1950s or early 1960s). But the impact of pre-modern vernacular fiction, in terms of a certain looseness of structure and language, on the big rambunctious novels of someone like Mo Yan is also very clear. And Mo Yan, who was born in the 1950s, would have been of the generation to grow up with relatively easy access to Journey to the West due to Mao’s approval of the novel. Now that China is becoming a very significant political and economic force in the world, I hope that more non-specialist readers will also really start to take China’s cultural and literary hinterlands more seriously in the way that so many general readers in China have familiarized themselves with European and American literary cultures — to look at the kind of literary afterlives of a text like Journey to the West on contemporary literary sensibilities in Chinese would be very fruitful.

I just have just one final question: what was easiest or what was hardest about the translation project you’ve been doing?

I must confess, I did find the language challenging as my training is in modern Chinese. Although the vernacular of Journey to the West is relaxed and expansive compared with highly compressed classical Chinese, it’s still a long way from modern spoken Chinese. I’m a huge admirer of the linguistic fluency of people like Geremie Barmé or John Minford. Now, those are people who switch so easily between contemporary and classical Chinese, and I only wish I had that proficiency myself. There’s a ton of technical language in the original novel about particular demons, kung fu sequences, religious practices, alchemical compounds, so this was all very time-consuming to figure out and to translate. The easiest part of the translation, I think, was striking up a rapport in my imagination with the characters. I found them to be highly relatable, flawed individuals with intensely human responses to situations and dangers: Tripitaka weeps constantly with nerves; Pigsy runs away at the first sniff of adversity; and Monkey jokes sassily and smartly in the face of really exceptional perils. And all the main characters snark and grumble at each other all the time — they’re not saints or paragons. I absolutely loved spending time with this cast of characters.