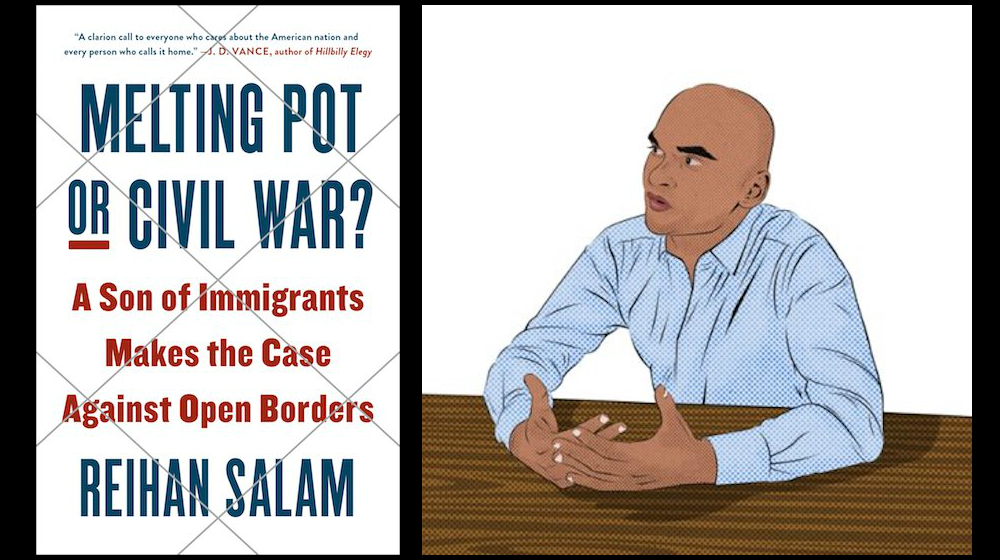

How might foregrounding contradictions and hypocrisies in conservative approaches to US immigration policy obscure contradictions and hypocrisies in progressive approaches to US immigration policy? How might fusing ideas from a wide array of ideological perspectives best help to promote economic well-being globally, and pro-immigrant initiatives domestically? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Reihan Salam. This present conversation focuses on Salam’s book Melting Pot or Civil War? A Son of Immigrants Makes the Case Against Open Borders. Salam is the executive editor of National Review, as well as a contributing editor of The Atlantic and of National Affairs. He is a board member of New America, and an advisor to the Energy Innovation Reform Project and the Niskanen Institute. Previously, Salam was a producer for NBC News, a junior editor at the New York Times, a research associate at the Council on Foreign Relations, and a reporter-researcher at The New Republic. With Ross Douthat, Salam is the co-author of Grand New Party: How Conservatives Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Your introduction situates Melting Pot or Civil War? within an “Age of Trump,” when “all conversations about immigration descend into…culture-war outrage.” It situates you personally by asking “And where was I?” and by first answering: “In an uncomfortable place.” As the son, brother, friend, neighbor of immigrants who might feel threatened by Trump’s aggressively anti-immigrant (not just anti-immigration) rhetoric, and as a conservative skeptical of progressive calls for increasingly open borders (calls that, in your account, do not sufficiently think through the long-term consequences such policies will bring for future immigrants or for American society), could you start to sketch that uncomfortable place from which this book originates?

REIHAN SALAM: I try to discipline myself to be open to a wide range of perspectives, and to reconcile clashing perspectives from people I consider thoughtful and intelligent. I grew up at a time when the foreign-born share of the US population was markedly smaller, when New York’s outer boroughs (where I lived) had a really different composition in terms of ethnicity and cultural identity. So I felt obligated to build bridges. I didn’t experience that as burdensome. I experienced that as a good fit for me. I’ve known people on different sides of these political and cultural divides. I’ve learned from these people. And it just seems the nature of class and of living in a stratified society that some folks can effectively curate their experiences of the world, and can avoid encountering people with whom they disagree, or can find it pretty easy to dehumanize and dismiss these people and not have meaningful relationships with them. But if every single person you consider intelligent and decent agrees with you, that will really undermine your situational awareness. And that was decidedly not the case for me.

Still of course, in this current climate, I have zero reason to expect people will give me the benefit of the doubt. Obviously, if someone reads the book, and engages with its arguments, that’s a different story. But the natural impulse, when encountering a discomfiting idea that doesn’t fit your priors, is to dismiss it. And I totally understand that. Everybody does it.

Well in terms of building bridges, or of starting to sketch a potentially non-polarizing vision for ongoing immigrant-infused American amalgamation, could you first outline the basic qualitative argument that this book makes (perhaps along the lines of: “Our number one priority should be ensuring that new arrivals and their loved ones can flourish as part of the American mainstream, not turning a blind eye as millions languish in poverty-stricken ghettos”), before we even begin discussing more quantitative questions of how many immigrants, with which types of work backgrounds, we might have the capacity and the commitment to help flourish in a US that “does right by all its citizens”?

Basically, this book’s big-picture thesis is that we need to conceive of immigration in multigenerational terms, versus thinking of immigration in the context of a single generation. Over the course of American history, native-born families have grown much smaller. Earlier generations had far more children. Our population, overall, was quite a bit younger. So immigrant inflows have a much bigger social impact right now, and introduce different tensions and clashes. Today I see us facing this really big challenge of how to ensure that children (children both of native-born folks and of immigrants) grow up to become adults who view American society, the American economy, the institutions that undergird our culture, as legitimate, decent, inclusive, and representative.

We also need an elite that represents and reflects the country at large, rather than an isolated elite hostile to the working-class majority. For a long time, in the conservative world, I’ve been something of a “squish” — someone who believes in one-nation conservatism, the notion that you need a social compact between the rich and the non-rich to ensure that working-class people, that lower-middle-class people, feel invested in the system. And for that reason, I believe government has an important role in helping to ensure people lead decent and dignified lives.

But a squish has to think through carefully how integrating immigrants factors into this question of cross-class harmony. Because if efforts at integration don’t succeed, then you’ll have this large and increasingly excluded class (both first- and second-generation) further complicating these political dynamics, with an expanding group feeling marginalized — as though the country’s institutions do not speak for them, do not work for them. And here we also should recognize that, over the next 50 years, about 90 population of net population growth will come from future immigrants and their descendants. So we can’t think of immigration as some kind of side issue, some symbolic issue. We should instead consider these questions utterly central to the future of the workforce, the future of our educational institutions, the future composition of our elite, and so much else.

Here I’d assume that a pro-immigration squish approach could acknowledge hypocrisies on the right (in terms of failing to connect today’s immigrant struggles to many Americans’ proud narratives of their own ancestors’ immigration, and in terms of celebrating a supposedly rugged capitalist economy that in fact gets heavily subsidized by undocumented, insufficiently compensated labor), and on the left (in terms of progressives, especially during this Trump presidency, appealing to the rule of law except on these fundamental civic questions concerning national identity, and in terms of cosmopolitans in this country’s urban centers failing to acknowledge the full extent to which their own day-to-day existence likewise benefits from the insufficiently compensated labor subsidizing their home construction and child / elder care and dinner bills). And here could you describe why such a pro-immigrant squish correction to prevailing hypocrisies might combine legalizing many of today’s longstanding undocumented residents (arrivals from more lenient times), and implementing a much less lenient approach going forwards?

When looking at the sweep of American history, you see a contrast between periods of consolidation and periods of expansion. These periods do not always get determined by explicit policy. During the republic’s early decades, the early 1800s, you have the Napoleonic Wars raging in Europe, number one. And number two, you have those big, prolific American families. So European immigration only plays a minor part during that particular demographic expansion, during which a British settler population become more distinctly Americanized. Even when you look at, for example, large flows of German-speaking migrants, the natural increase among English-speaking settlers and their descendants still dwarfed those flows.

Then later, in the 1840s and 1850s, you have a renewed wave of European immigration. You also have a big and fierce response to that wave, partly because it differs somewhat in its cultural character. Native-born Protestants respond differently to this Catholic wave than to their Protestant co-ethnics. So again, you can’t just look at American history and say that we kept our borders wide open until date X. In fact, even with immigration, we had all of these idiosyncratic state-based policies — particularly for seaboard states, which might have their own policies for excluding so-called paupers. Only later did the federal government assert control over this very chaotic system. And of course, changing technology played its part in stimulating migration flows by, for example, lowering the cost of a trans-Atlantic voyage, or facilitating the spread of information about employment opportunities, living conditions, and the like.

By the early 1900s, you see these truly enormous immigrant inflows. But you also see a huge amount of return migration. From Southern Europe, for example, upwards of 40 percent of migrants ended up returning home. Here again, we might have this mental model that immigrants settle, that they form deep ties. But you can’t say that this plays out consistently across American history.

When people talk about our mythic immigrant past (whether from a right or left perspective), they tend to get a lot wrong. Much of how we today talk about immigration actually dates to mid-20th-century America (during a time when this country had historically low levels of immigrant replenishment), when many second- or third-generation Americans were really making a kind of political argument about how to interpret our ambiguous past. In the 1950s and early 60s, people could look back at these preceding immigration waves with great nostalgia, and they engaged in a kind of myth-making that served their political purposes.

Those very large immigrant inflows absolutely benefited natives. But you also had a great deal of poverty in those immigrant communities. And so long as these communities could keep replenishing themselves with new arrivals, they also could stay quite isolated in ethnic terms. You didn’t yet have the cultural fusion that we associate with the melting pot. You didn’t have high levels of intermingling and intermarriage.

And the places where you did have more intermingling among European communities also typically had a large influx of black migrants. European immigrants and native-born European Americans started to define themselves collectively as “white,” against this black influx. So we also need to incorporate that very uncomfortable story into this really romantic notion of American immigration. When people say “Oh, my great-grandparents arrived and did X, Y, and Z,” we first of all should recognize that European assimilation went hand and hand with this ugly and difficult process of race-making and of marginalizing other groups.

We also need to consider the radically different economic and institutional contexts within preceding eras. For most of the last century, employers in manufacturing and agriculture had an enormous appetite for low-skill, low-wage labor — an appetite which has declined over the past 30 years. Today, by contrast, the argument for immigration comes more out of humanitarian considerations and a kind of cosmopolitan ethic. This argument also often gets seen through a lens of racial justice. But you don’t have the same broader coalition for immigration expansion. Today’s employers want an ongoing flow of high-skilled immigrants, whereas low-skilled immigration has become more of an afterthought, thanks in large part to globalization, and more specifically to China. At present, if you want to profit from low-skill, low-wage manufacturing, you can make use of offshoring. You can make use of these multi-country / multi-firm networks to build products in different ways.

The need for low-skill, low-wage immigration today comes primarily from the service sector. But the service sector, much more than the manufacturing sector, works really differently from one society to the next. In some Northern European societies, for example, restaurant meals and a variety of in-person services cost much more than in the US. But service workers in these societies also have a much better chance of making a decent living wage. In the US, we have adopted a different set of business models, which reflect a kind of underlying stratification in our society, and which can reinforce an underlying inequality.

And then you’d asked about President Trump, and about hypocrisy on the right and left. I actually think President Trump’s immigration message has been more about reaction than about substantive policy considerations. From the 2016 campaign to his current presidency, Trump has taken a wide range of positions. Earlier in his presidency Trump said “Hey, I’m open to some larger deal to address the unauthorized-immigrant population in the US.” Then at other points, he seems to take a very different tack, often in response to pressure from immigration hardliners. But what has been consistent, what I think his supporters have found resonant, is this emphasis on the national interest, this idea that our immigration policy ought to serve the interests of American workers, of the country as a whole.

At the same time, of course, Trump uses this really sharp, brutal language that you could understand as a form of signaling. He basically sends the message that: “You might balk at the discrete ideas I’m offering, but you at least see no ambiguity on the question of for whom I’m crafting these immigration policies.” One Trump tactic that especially seemed to resonate with Republican primary voters was the Muslim ban, tapping concerns about security. As a Muslim American, as the son of Muslim immigrants, I’m predisposed to find that idea wrongheaded. But it comes from a basic conviction that we should not senselessly endanger our people in service to an abstract ideal. And for these debates about security and immigration, you’ll often see (in the European context, for example) that security concerns actually stand out most in regards to the second generation. The children of refugees and guest-workers might become susceptible to radical ideology, perhaps out of a feeling of exclusion from the cultural mainstream. Again, this happens only among very small numbers of people, but those people do typically come from the second generation.

Here we come back to thinking about immigration in multigenerational terms. Someone might argue that our societies have not done enough to combat racism and discrimination, or to make the necessary social investments. But again, this argument presupposes that we ought to make great sacrifices to do the supposed morally righteous thing — whereas somebody else might say: “So you expect us to change and to make substantial sacrifices, in order to do what you, outsider to my community, consider the right thing?” Again, many voters found President Trump at least directionally right on this point, and the fact that people outside this world so denounced and condemned Trump’s approach only affirmed that Trump didn’t care about the approval of those who adhere to a cosmopolitan ethic.

As for me, I agree with some of Trump’s prescriptions, and disagree with many others. And I’ve argued repeatedly that Trump actually will undermine the cause of immigration enforcement and immigration restriction. But I also said throughout the presidential campaign: “Look, other candidates need to be aware that voters want to know whether or not you favor a policy in the national self-interest. That comes first.” And I don’t think Trump’s rivals did a very good job on that front.

Here I also wondered how you think Democrats have done on these arguments of national self-interest. For example, I’ve talked to Democratic leaders (leaders with political values I largely share) over the past year who will pivot pretty unreflectively from pointing to the social costs of an impending wave of job-displacing automation (say as driverless cars disrupt a trucking industry employing many rural Americans, a car-service industry employing many urban Americans), to calling for increased immigration to staff all the emergent service-sector jobs American citizens will decline to take (say in providing expanded health-care for aging baby boomers), apparently without realizing how problematic this particular confluence of social predicaments and policy recommendations sounds to many of the most occupationally vulnerable Americans. And from that future-oriented perspective, the long-term ethical and economic consequences of open-borders immigration have started to look much more complex to me. But your book suggests that we don’t even need to look to the future to see how this type of self-contradictory policy vector plays out, that we already have been living through such contradictions for the past 30 years, during which we’ve never finished building a long-promised bridge to the 21st century, to connect all American workers to a tech-driven economy. Instead, we’ve provided employers an ever replenishable option to find somebody younger, more nimble, more mobile, more willing to accept labor conditions that a longer-term employee might consider an intolerable downgrade. Could you take that late-20th-century legacy and describe what a future-oriented political leader, either from the left or right, needs to learn from it today?

We can start from how often such arguments neglect the basic fact that the economy is dynamic. Often you hear people say “We need to recognize that the economy will adapt to the arrival of these new workers, that as the workforce expands, so too will consumer demand,” and I absolutely agree with that. But this process also could work in the opposite direction. The economy could also adapt to certain forms of labor scarcity — for example, by having firms embrace offshoring, by having firms embrace automation, by having firms retrain their workers. In Copenhagen or Oslo, you find a much more skilled labor force, and so these societies have had to retool how they do business. How should employers respond to a labor force that doesn’t want to take on difficult, potentially dangerous jobs? First, you make those jobs less dangerous (and also more productive) by investing more capital, by investing more in long-term training.

In the US we have this fascinating situation in which employers have grown so used to slack in our labor markets, so used to having people desperate for work, that these employers literally have forgotten how to raise wages, how to train productive workers, how to invest long-term in their employees. They don’t feel equipped or even motivated to make a lot of institutional changes and really take seriously the fact that our economy right now just wastes the talents of huge numbers of people, immigrants included.

Right now, roughly two million immigrants with college degrees in the US (one of every four) can only find low-skill jobs or can’t find work at all. One could argue that their particular skills don’t present a great match for the kind of employment opportunities they have in the US. Who knows? But from a broader perspective we can see how immigrants often get stigmatized, how they often get ghettoized, how they may not have the social networks they need to find more remunerative employment opportunities. Employers get to underpay these disciplined and capable workers, relative to what they bring to the table, and you can see why employers are pleased by that.

So where’s the harm? As an immigrant, as someone uprooting yourself from one society to another, maybe you’ve decided to take that risk. Maybe you prioritize being the author of your own fate, even if this means you will in some sense be taken advantage of. But when it comes to this person’s children, that raises big and profound questions affecting our politics.

About one-fourth of US immigrants are unauthorized. And low-income folks with modest skills who do arrive here lawfully don’t naturalize at very high rates. So in terms of the political implications, we actually don’t have large numbers of working-class immigrant voters. We therefore don’t really know how satisfied they are with their wages and working conditions. Some might consider their current situation great. But then what do they think about the prospect of their children finding themselves stuck, finding themselves in a very difficult position of struggling to enter the middle class? Again, because we have this very sentimental and weird debate about the immigrants arriving today, we often overlook these serious long-term challenges.

Other societies, by the way, approach all of this quite differently. They might say “We will welcome migrants, but they will not become citizens, and neither will their children.” Singapore, for one, literally deports guest-workers who become pregnant. Officials stringently enforce these rules and regulations, because they essentially treat migrants as disposable. They consider questions of integration immaterial. They just want a low-cost source of labor, and they’ll be quite content to import low-skill, low-wage labor so long as doing so is cheaper than deploying a machine.

Some folks suggest the US should try do the same. I’d consider that approach a grave mistake. But you do have to choose a direction. You can’t just say: “For now, we’re not worried. Maybe in 20 or 30 years the economy will look different, with a lot of working-class US citizens finding themselves under strain, and we’ll have to make bigger investments to include them in the economy. In that case, we’ll just deport all of these foreigners we’ve invited to do our dirty work.” That’s not how it goes. Once you welcome workers, and once they establish roots in our society, you can’t just toss them aside. They become integral parts of the whole, and when they face serious economic challenges, all of us will either bear the burden or reap the consequences.

To pick up now your Melting Pot or Civil War? title: something tells me we both took AP US History. My year at least, everyone had to write an essay addressing the seemingly perennial “Melting Pot or Salad Bowl?” debate on American national identity. Your title of course sounds quite alarmist by comparison. But as I continued reading, I could appreciate this book’s more sustained analytic case that public inertia on current immigration policies could lock in ever widening social disparities that most Americans eventually will find intolerable and / or existentially threatening. So here could we take an example of an easily extractable (and then inflammatory-sounding) statement such as that “Today’s poor immigrants are raising tomorrow’s poor natives,” and place this statement amid a broader social diagnostic that doesn’t seek to scapegoat immigrants, but rather to problematize our nation’s lack of long-term policy vision? And could we try to arrive at your stark warning to Americans of all political stripes (from Trump-enthused nativists to Fire Next Time-quoting progressives): “Do you think working-class young Americans of color will shrug and accept their inherited disadvantage? Or will they be drawn to politicians who promise to do something about it, even if it means breaking with the established order”?

First, I’d note that no real dispute exists among serious scholars about the strong relationship between educational attainment of immigrant parents and of their children as second-generation American citizens. In the US, we see a serious bifurcation among immigrants, with some entering the country with low levels of educational attainment and English-language proficiency, and others who begin from a more privileged position. This gap says nothing about whether or not people have a strong work ethic. Basically, whether people arrive as low-skilled or high-skilled workers, they have come here to work and to thrive. But even exceptionally hard-working people might bring to this country quite different sets of advantages and disadvantages. And when you look at the changing US labor market, you see certain types of skills becoming increasingly important determinants of success. You also see rising labor-market inequality. So in terms of the statement that today’s poor immigrants are raising tomorrow’s poor natives: I mean, hopefully everybody can agree with this fact about the reality of life in a stratified society. That’s why people like me want to make the investments we need to help break this intergenerational transmission of poverty.

I also want to stress that immigrants are as diverse as any other group of human beings. Like any of us, they get powerfully shaped by their upbringing. They get powerfully shaped by the class-specific resources that defined their lives prior to settling in the US. One of the most noxious things you’ll see in the immigration debate is when people say: “Look at how this particular ethnic group is flourishing. Look how well their kids do in school,” as if to imply that groups that don’t fare as well are somehow defective. This offends me to my core, because differences in educational and labor market outcomes among different immigrant groups overwhelmingly stem from differences in selection — differences in who can make it to the US in the first place. Some immigrants groups are mostly drawn from the elite of their particular society. Because of the advantages that this elite status already has afforded them, they might climb into the elite of the US (or certainly their children can). But for immigrants already burdened by disadvantage in their home countries, disadvantage that can follow them to their new lives in America, their children have a much, much harder time. And as a society right now we just kind of pretend that this doesn’t happen, or that we actually don’t have to worry about making good on our promise of opportunity for all comers.

Now if you want to make the necessary investments, if you want to say “Look, many native-born and many foreign-born people in this country really need our help,” if you ever hope to break the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage, you’ll have to be humble about how much we can open up our borders. Because when you look across different countries, you see a distinct pattern. The countries most open to low-skilled immigration typically do not invest much in migrants and their children. These countries typically welcome large numbers of guest-workers, but do not fully incorporate them into society. Societies which have tried to remain high-investment egalitarian societies, even while incorporating large numbers of disadvantaged folks, have found themselves under intense strain. Sweden is one example, and provides a notable difference from Norway and Denmark, both of which decided long ago: “Okay, we need more restraint. We do want to welcome some migrants for humanitarian reasons, but we need to welcome them in more modest numbers — to make sure that we can integrate them.” Sweden by contrast tried simply to say “We have opened ourselves to refugee migrants.” But they’ve found it extremely difficult to incorporate these migrants into Sweden’s high-skill, high-wage, high-productivity workforce. Instead, they’ve now seen long-term unemployment, along with increased social tension, and essentially have slammed the door shut more recently in response to these kinds of political, cultural, and economic concerns. And I have to assume a similar outcome if we want both to become more open to immigrants and to make bigger social investments.

Senator Kamala Harris has called for a tax credit that would supplement the incomes of households earning less than $100,000 in certain cases, based on the idea that our market economy does not sufficiently remunerate people who have limited or modest professional skills. Well, when you talk about new arrivals with limited skills, the wages these workers make likewise will not allow them to lead dignified lives by American standards. Of course, we could say “Well, if these people can lead a decent, dignified life according to their native country’s standards, then that’s enough.” But that would require thinking of these new Americans as a population of permanent strangers, a permanent labor underclass, an underclass that will include their native-born children. So here again, I’d say that we very well might need wage subsidies to ensure everybody can lead dignified lives, but this also means that welcoming large numbers of low-skill newcomers into any expanded social system will introduce the types of serious tensions we’ve already seen in other societies.

Here could we also take up the Patricia / Carolina, amalgamation / racialization thought-experiment you offer, in which two hard-working immigrants, left to the vagaries of our market economy, end up on quite different trajectories for long-term economic security and social inclusion? And could you make the case for considering these two lived trajectories less through a lens of “assimilationist” or “authentic” Latina identity, and more through an examination of which proactive policy steps might best create broader structural conditions to address such class stratification and ethnic balkanization?

Well first, because we so often differentiate between “successful” and “unsuccessful” ethnic groups, I wanted to present both Patricia and Carolina as being of Mexican origin but bringing very different skills and resources to the US, where they enter quite different communities from the start. Patricia arrives from Mexican society’s highly educated strata, and immediately finds herself in a very diverse work environment, rubbing shoulders with both people from other immigrant backgrounds and with native-born people. Patricia operates in environments dominated by the English language. Patricia might truly embrace her ethnic identity (highlighting this ethnic identity might even help in some ways as she navigates her new professional world), but her objective experience of ethnicity does not constrain her. For a variety of reasons, Patricia has opportunities, and can become part of social networks giving her access to further opportunities, as she ascends into the American elite. None of this makes her a good or bad person. It just reflects how she has been incorporated into US society. Similarly, because of her relative affluence, Patricia likely lives in a more affluent, more educated community. If she gets married, she very well might intermarry, probably someone with similar educational and income levels. Again, that all could be good or bad in personal terms. But Patricia probably will end up well-positioned to transmit various social advantages to her children if she has any.

Carolina, by contrast, moves to the US with much more limited professional skills, and thus more constrained economic opportunities. Carolina settles in a community dominated chiefly by people from her native country. Carolina might work incredibly hard, but her social network still will differ from Patricia’s. Carolina’s social network won’t open up equivalent opportunities. So Carolina most likely will marry someone who also has more limited professional skills, and their children (even in a family of bright, incredibly hard-working people) will face much bigger barriers as they try to navigate American society.

And frankly, the policy implications for a thought-experiment like this could go in all sorts of different directions. But you have to recognize the extent to which class-specific resources shape how individual immigrants navigate American life. To talk about how “Asian” or “Hispanic” migrants fare would be foolish. Or somebody from an African country who arrives here as a refugee migrant, who has experienced all sorts of challenges growing up, who already has dealt with all sorts of labor-market obstacles, will have a very different immigration experience than someone from that same country who earned a PhD, and who already has resided in London.

Here again though, I do want to contest this notion that on the individual and group level assimilation isn’t happening. That’s simply false. Immigrants are absolutely learning English over time. Immigrants’ children overwhelmingly speak English, often as their sole language. But in a stratified society, people assimilate in different ways. And I think of the US as having a mainstream, in which ethnicity does not necessarily determine your fate. It doesn’t have to dictate where you live. It doesn’t dictate the opportunities available to you. But for members of marginalized minorities, for groups outside this mainstream, ethnicity becomes much more powerfully determinative, in a way that really puts into doubt the American dream for members of your community. This has always been one of the central facts about American life. We have tried and failed to overcome this grave injustice, which also applies to many immigrants and their descendants. If you find yourself stuck on the labor market’s bottom rungs, and you just cannot climb into the middle (and certainly not to the top), and if you think that this kind of opportunity does not exist for you and your community, then that poses a very, very serious problem for the legitimacy of our governing institutions.

Returning then to broader policy outlines: prioritizing high-skilled immigration of course would mean at least partially departing from our present emphasis on family-based admissions priorities. Could you sketch your sense of how this current family-oriented selection itself can further isolate tight-knit immigrant networks, say by providing an ever replenished community of recent arrivals, to whom one might feel both comfortingly and constrictively tied? And amid the hostile approach of this Trump administration, I find it hard to call on immigrants to embrace any even more discomfiting social circumstances. But could you make the case for how a recalibrated selection process that ranks potential immigrants on a variety of factors including (though deemphasizing) family connections could in fact help to foster a more welcoming and intimately enmeshed sense of national identity?

This gets to another way that our current policies mislead would-be immigrants. People who want to settle in the US are not inert or naive or passive. They respond to incentives. These often exceptionally motivated people really do think: Okay, I can see how moving would benefit my family, so how does this selection process work? How do I better my chances? But we base our immigration selections on incredibly arbitrary and maddening categories. We have over four million people on the waitlist for green cards, with many people lingering on this waitlist because we have these very complicated country caps, and numerical limits, and preference categories. Other people wait for family-preference visas. And especially when you wait for a family-preference visa, you can’t proactively do anything to move up in the queue. Securing remunerative employment in the US doesn’t help. Learning to speak fluent English doesn’t help. Getting better educated or developing new professional skills doesn’t help.

Other countries do a better job with this, prioritizing potential immigrants who take specific steps (again, this has nothing to do with certain individuals or groups possessing fixed traits or qualities). Similarly, if we said “Okay, you could take these steps to avoid getting ghettoized and marginalized, and to help you navigate American life, and thereby improve your chances,” many people would leap at the chance to do that. We have, for example, 1.5 billion English-language learners around the world. This is not a niche phenomenon.

Or at present, US citizens can bring their adult parents without limit into this country. Now that sounds very decent and humane, but it also means that current immigration policy makes our overall population older rather than younger. If you look at the early 1980s, immigrants over the age of 50 represented a small fraction of all immigrants in the US. But today, about 20 percent of first-generation immigrants are over 50. And of course a lot of those folks need health insurance. They need care provided for them in various ways. So some Americans might reject the idea of simply saying: “If you bring your older relatives, that’s a beautiful and wonderful thing. But we want to ensure that you can provide for their long-term care and health insurance, because we need to provide for a lot of low-income folks already in our country.” In fact, some Americans no doubt would angrily reject this idea. But most immigrants, I suspect, would accept it. And even many Democratic voters would consider that pretty reasonable, though it would be a big departure from what we do right now.

So just some very simple straightforward tweaks to our immigration policies would encourage Americans to believe in the system, would help those wishing to immigrate to navigate the system, would make it all a lot less arbitrary, and more sensible and decent. But a lot of Americans only can hear this as: “We want to exclude whole classes of people, because we consider them inferior.” I think that’s totally, totally wrongheaded. And more broadly, I’d say that when you compare any proposed immigration reforms to our current status quo, you first have to understand how crazy this status quo is, before you even can address which changes might help.

Of course if one advocates high-skilled immigration, if one pushes to modernize our economy at an unprecedented pace, one also faces the prospect of exacerbating problematic inequalities now on a global scale. So could you clarify further Melting Pot or Civil War?’s complementary commitment to proactively assisting other countries (particularly countries predicted to provide the greatest number of future immigrants) with cultivating their own sustainable economic growth? Here could you first make the ethical case for, say, virtual immigration, or even for coordinated US retirees’ emigration to nearby countries — as potential means of addressing the economic precarity of a much greater international population (particularly among impoverished communities for whom an open-borders America would still be inaccessible)? And then, throwing ethics aside, say for a more self-interested immigration-resistant US audience, could you make the converse case for why American efforts to promote sustainable economic development abroad can do much more than any protectionist trade policies to protect American workers back home?

The big-picture question here for me comes from people saying: “Reihan, how dare you accuse pro-immigration advocates of being for open borders?” But if you want to prioritize moral imperatives, then you should certainly be willing to consider doubling immigration to the US. But even that number would be trivial when we consider the number of people around the world hoping for a better life.

Over the next few decades, 2.5 billion people will move to cities in search of opportunity. And most international migration already is South-South migration, from one developing country to another, with most people lacking the resources and the wherewithal to reach American soil. So if you wanted to make the case for welcoming and assisting all these billions of people who would love to live in the US, you’d probably get even a lot of awfully pro-immigration people balking at that prospect. No one in this debate, no Democratic politician, is actually going to say: “Let’s welcome hundreds of millions of people from South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia and elsewhere.” No one says that. They might call for tweaking things a bit, but they’re not even remotely talking about what it would take to really address this entrenched poverty around the world. But this is the actual moral challenge, a moral challenge that can’t be met by inviting a small token percentage, a few additional hundred-thousand folks, to basically occupy menial jobs that could be done by machines, or could be done virtually, or could be offshored from the US.

This bigger moral challenge is about trying to ensure broad-based, inclusive economic growth on a global scale. That broader project could adopt various strategies. One strategy would involve leveraging this reality of South-South migration by, for example, creating charter cities. We would create designated territories where we could partner with developing countries to make large infrastructure investments, large human-capital investments, to develop cities capable of creating employment opportunities and meeting the needs of people with a wide range of skills. I think this idea has a lot of promise, and gives one good reason to truly believe in and support overseas-development assistance used intelligently.

When you look at Africa and South Asia, with their very young and expanding workforces, these places will need to create meaningful opportunity. And with both Africa and South Asia separated from the US by vast stretches of ocean, it’s really Europe and to a lesser extent East Asia that will see intense migratory pressures keep building from those demographic changes. But that doesn’t mean the US should just fall asleep at the switch, right? The mere fact that people can’t cross overland from Pakistan to the US doesn’t mean we should ignore their fate.

Now on this question of American retirees moving to Mexico: again, I’d start from the big-picture perspective that large-scale immigration can create a huge amount of dislocation for communities and families, but so too can large-scale emigration. Net immigration from Latin America has for the most part slowed down, especially from Mexico, where you might actually now have net emigration. We have had a recent surge of asylum seekers from Central America, but Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the new Mexican president, talks about how he wants to make emigration from Mexico optional and not necessary. He wants to ensure that ordinary Mexicans have opportunities within their own communities. With Mexico and the US, we should really want to see economic convergence, to see Mexico become a more productive and affluent country. And though Mexico has made some progress, it still has a long way to go. We ought to do more to help Mexico, and ought to do this in ways that will benefit us as well. Already, for example, the López Obrador government has said: “We want to welcome Central American migrants. We will help provide them with opportunities.” This can help Mexico become a more dynamic, prosperous country. At the same time, with the physical and cultural distance far smaller between Mexico and some of its Central American neighbors, there’d be less disruption of existing family and communal ties. Everybody benefits from this fruitful and positive arrangement.

Another way to assist Mexican economic development could involve retiree migration. One million US citizens reside in Mexico, and that number could grow substantially. You also have a large and increasing number of older Mexican Americans, many of whom may well want to retire to their native country. One big barrier right now is that you cannot access your Medicare benefits from Mexico. But the reality is that you can find high-quality medical care in Mexico, potentially at a much lower cost. So you can imagine a scenario in which the US and Mexico join together in ways other countries have done, with us sending large numbers of retirees to live in Mexico as expats, and creating this large, potentially quite lucrative service industry in Mexico — which will allow more workers to stay in Mexico, and stay in their communities, and will give them new opportunities much closer to home.

Spain, for example, has become one of the world’s most affluent countries, but that wasn’t always the case. One thing Spain did was open itself to retirees, many from Northern Europe. That was one essential element to Spain’s economic takeoff.

López Obrador also emphasizes domestically distributed economic development. He wants to figure out ways in which everybody doesn’t have to move to the biggest Mexican cities (with the countryside abandoned, empty of opportunities for residents). And presumably most US retirees wouldn’t end up in Polanco.

Absolutely. And then in terms of broader regional development, when you look at the experience of East Asia over the past 40, 50 years, you see really remarkable economic convergence, extensive institutional reform, amazing human progress. Those who suggest that folks in South Asia or Africa or Central Asia can’t do the same just dismiss these societies’ capacities to build on existing institutional and cultural capital. Here again, migration will remain important and valuable, but many other opportunities also will exist — say for service-sector-led development.

For virtual immigration, the basic premise is that many jobs currently done by people in the US will soon be done by machines or by combinations of machines and people — as today happens with telecommuting to the US. You see this in the software service sector, where people already interact across vast distances. And you can imagine this arrangement applying to lots of other service industries as well, especially as you see a move toward stronger broadband and telepresence. Until now, service workers have been largely shielded from offshore competition. The further development of virtual immigration will change that. This challenge for our own workers will create opportunities for employment in other parts of the world. I’m optimistic that the rise of virtual immigration will ultimately prove beneficial to all involved, but there’s no question that it will cause considerable dislocation.

And maybe (as a side point) will help to preserve cultural diversity on a global scale as well.

That’s not a small point. That’s actually a really profound point, because these arguments unfold in such funny ways. People constantly switch from one side to another. So they might say: “We want pluralism and diversity. We do not want everyone conforming to the American norm.” But then when you try to address America’s excessive cultural fragmentation, these same people might say: “How dare you? Of course everyone’s assimilating.”

Some would-be immigrants probably do feel eager not just to move, but to uproot themselves, to basically surrender central elements of their native culture (and by the way, when you immigrate to the U.S, one way or another, whether you like it or not, your ties to your native culture attenuate). And of course some people do want to preserve their distinctive native cultures, and to let these flourish. At the same time, they do want higher incomes. They do want to prosper, but they want to do this all within the context of their native communities, rather than by uprooting themselves. I mean, as ridiculous as it sounds, I live 25 minutes from where I grew up. I see my parents about once a week. I really value that, and I sense that many other people, if they had the chance, would much prefer to see their native communities develop collectively, rather than to leave these communities behind to better one’s personal economic condition.

So hopefully by now we have established a broader argumentative context for your preferred policy package, a package that today would include legalizing long-settled undocumented immigrants, tightening future selection policies by prioritizing high-skilled individuals, and strengthening enforcement efforts (for example through compulsory E-Verify employment checks). Hopefully we have illustrated how such a package might even further a pro-immigrant agenda, primarily by giving recent lower-skilled immigrants (and their native-born counterparts) “a modicum of breathing room.” But we still face at least a couple substantial argumentative snags stemming from historical precedent. Here I’d start from the concern among immigration restrictionists (a group one can disagree with, but here nonetheless sympathize with) that past immigration package deals such as the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act have ultimately produced one-sided amnesty outcomes violating the spirit of promised compromise. At the same time, the legacy of trade policies like NAFTA has reinforced left-leaning characterizations of a neoliberal (only superficially progressive) internationalist regime promising to bring all workers into the 21st century — just so that it could sound nicer when it fired them and left them to fend for themselves. What’s your most effective rhetorical strategy, when addressing either crowd, for conveying how and why a contemporary compromise will break from both such precedents?

There are thinkers on both the right and left very concerned about this broad group of heartland Americans who feel excluded in various ways. And though we haven’t discussed this quite as much in our national conversation, we also have a quite large number of disaffected people in the cities. Those two constituencies can seem quite at odds with each other. They can seem quite different from each other. But they actually have a lot of shared interests. And again, we just don’t know very much about what immigrants and second-generation Americans think, because they haven’t yet really flexed their political muscles to match their numbers. But this second-generation group, particularly the working-class members, will face some very serious headwinds in the next wave of globalization. And the heartland group — already facing serious headwinds — might end up recognizing it has a lot in common with this urban second-generation group.

I’ve tried to put together something of a package deal that speaks to both groups. Republicans most generally have offered proposals combining some kind of legal status for the DACA-eligible population, while in return reforming family-based migration, establishing mandatory E-Verify, etcetera. These packages remain close to impossible though, given the maddening complexities of a system that includes all of these folks who entered the country as minors, all of these unauthorized immigrant adults who have lived in this country for 10 years or more (with something like 40 percent of them having US citizen children), and other adults with US citizen spouses (which presents its own bureaucratic complications).

Still, we’re talking about an incredibly sympathetic population. We’re talking about a very rooted population, with the migrants who remain disinclined to leave partly because they have such strong family ties. Realistically, if you ever want to move to more stringent enforcement, that enforcement has to focus on much more recent violators. And you’ll need a similar kind of compromise for the DACA-eligible population, another very sympathetic part of the population, trapped in this weird place in part because of years of under-enforcement. Both immigrants and a lot of employers have benefitted from that, so again you’ll need some kind of larger compromise. And most importantly for me, when I think about these larger bargains, I most of all want to make sure that we invest in poor and working-class youth, both from immigrant and native-born families. It happens that a disproportionate percentage of this group has recent immigrant origins. But the goal really is to bring all communities into the American mainstream.

We probably also should have acknowledged from the start that this book does not focus on the immigration of political refugees, say those fleeing a violently destabilized early-21st-century Middle East to which the US should feel a strong sense of obligation. It doesn’t say much about an ever expanding range of climate refugees, or about how emigrants departing precarious Central American or Caribbean states can make their own historical case for US culpability in their plight — regardless of whether our government opts to define them as political or economic refugees. I don’t want to ask much about what your book doesn’t address, so could you clarify why the specific range of immigration-related topics that you do prioritize here seemed the most pressing?

There is an important role for humanitarian immigration. However, I again believe that you need to think about this rigorously. You have to consider questions of scale. You have to consider the resources we’ll need to devote. And the classic definition of a refugee suggests someone who will never be in a position to return to their native country, but we do see situations today that might allow for a return at some point — which might involve more of a temporary dislocation. Or you have these situations today where huge numbers of forced migrants travel to neighboring countries. Here a tradeoff often arises between affluent countries providing resources to settle forced migrants in neighboring countries, versus providing for these people by resettling them in the more distant affluent countries.

Think about all the financial resources required to provide people with basic medical care, and to fully incorporate them into the US economy, and how much farther those same resources would extend if this took place in Jordan. Right now, Canada and the US annually admit however many thousands of displaced refugees. But recent humanitarian crises have produced millions of displaced refugees. We might accept a modest number of people, to send this political signal that we take these developments seriously. We might care deeply about these refugees. We might invest in them. But we still haven’t addressed this humanitarian crisis at scale.

And of course we expect that people who enter our country on a humanitarian basis will need assistance. That is right. That is proper. They do not get subject to the so-called public-charge determination under US immigration law. But when huge numbers of people who come on a non-humanitarian basis likewise need wage subsidies and safety-net benefits, then I suspect this makes Americans less inclined to welcome migrants on a humanitarian basis. I actually believe that reforming the non-humanitarian immigration system would encourage more generosity on humanitarian cases.

Finally then, let’s assume our present discussion will frustrate at times left-leaning readers. Progressing through your book, I did keep wondering if and when (standing, let’s say, before which conservative audiences) you palpably sense untroubled acceptance of an America in which so many disadvantaged people of color will continue being confined to physically, culturally, economically marginalized neighborhoods — supposedly with little connection to one’s lily white (or maybe now more proudly multicultural) suburb a few highway exits further on. Do you ever directly address with such audiences what in Melting Pot or Civil War? remains the mostly implicit specter of America’s longstanding tolerance of racialized ghettoization, and why this can’t be our default paradigm going forward? How do various conservative audiences (whom I no doubt am overgeneralizing and stereotyping right now) respond to that particular argument?

I actually never do get that reaction. At least I haven’t to date. I’m sure those audiences do exist. But I’ve traveled around the country, speaking to many different conservative audiences, and I’ve found a deep interest and concern about whether low-income Americans of all colors and creeds feel bought in, and feel that the American dream is available to them. I’ve found a deep recognition that if more Americans do not feel that they can pursue this dream, then we will only have more tension and anger and rancor in our politics going forward. I really sense that fundamental concern.

Of course I encounter various disagreements about the causes of between-group inequality, but also a broad sense that our elite needs to be much more representative in the years ahead. I mean, look, we conservatives are very concerned about security. We are very concerned about stability. We are very concerned about legitimacy.

I largely avoided ideological labels in this book. I wanted to make sure my argument wasn’t narrowly partisan. But fundamentally, the book comes out of the Burkean insight that society is a compact between the living, the dead, and the unborn. Often an approach that might make sense if we only had to think in terms of a single generation just doesn’t make sense when we think about the children and the grandchildren involved, and who will end up recognizing each other as fellow Americans. I see immigration as a way to discuss these much larger issues of civic solidarity, and the various strains and various commitments in a big, sprawling, diverse, democratic society like our own — particularly while going through wrenching and highly uneven change. I grew up in working-class and lower-middle-class immigrant communities of color. But I’ve also taken part in various professional milieus, with lots of highly educated and affluent people. And the disconnect between those two worlds feels really, really extreme to me. That has resonated with conservative audiences.