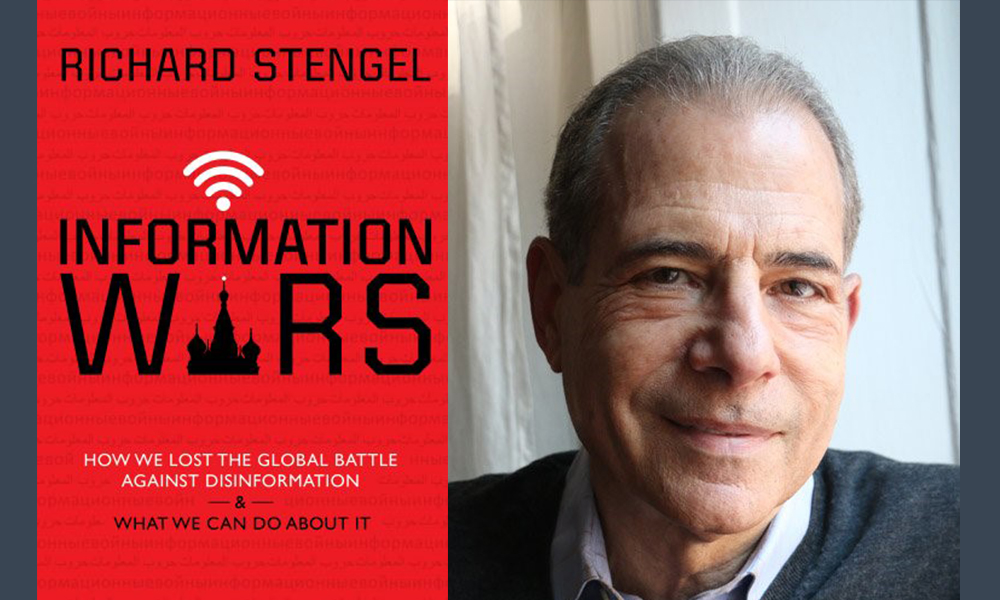

How might our government best tell (and best enact) its own democracy-affirming story? How might we as citizens help to improve that process? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Richard Stengel. This present conversation focuses on Stengel’s book Information Wars: How We Lost the Global Battle Against Disinformation and What We Can Do About It. From 2013 to 2016, Stengel served as Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. Before working at the State Department, he was the editor of TIME. From 1992 to 1994, he collaborated with Nelson Mandela on Long Walk to Freedom. Stengel’s other books include Mandela’s Way (on his experience working with Mandela), January Sun (about life in a small South African town), and You’re Too Kind: A Brief History of Flattery. He is an NBC/MSNBC analyst, and lives in New York City.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we open with your working definition of “disinformation”? Could you describe what makes disinformation (even more than misinformation or propaganda) so corrosive particularly for liberal democracies — premised upon free people making intelligent choices, and prioritizing public conversations that invite difference, dissent, balanced debate?

RICHARD STENGEL: Disinformation is the deliberate use of false information to deceive for some strategic purpose. Disinformation differs from misinformation, which comes about less deliberately or again less strategically. We all commit misinformation all the time. Propaganda is more subtle and complex, and for me doesn’t have the same completely negative connotations that it does for many folks. Its 15th- or 16th-century root-word (propagare) points back to the propagation of the faith. So by definition every country engages in some form of propaganda.

But in this new book I focus on disinformation as developed by both state actors and non-state actors for nefarious purposes. The book’s two most striking examples come from ISIS efforts in 2014-2015 to first create the myth and then establish the fact of the caliphate, and Russian efforts in 2016 to interfere with our election.

I consider disinformation so dangerous especially for democracies because I can’t forget Thomas Jefferson’s words, from the Declaration of Independence, that “Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” How do we achieve this consent of the governed? Well, we only do so if the governed themselves have true and sufficient information. Jefferson said a country cannot be both ignorant and free. Our democratic process requires the free flow of information, as protected by the First Amendment. We still live under this belief (maybe a bit outmoded now) in a kind of democratic marketplace of ideas, in which ideas can compete against each other and the best can win out. Disinformation subverts this whole process, deceiving and misleading people, so that selecting the best ideas gets much harder. And most perniciously, the abundance of disinformation we have today makes many people question the veracity even of verifiable information. They feel that maybe they can’t believe anything. That quickly becomes pretty perilous for democracies.

Your book asserts that while disinformation has existed throughout human history, it picks up acute force in a present-day social-media context, with public communications taking place at an unprecedented volume and speed, almost entirely free of editorial intervention and accountability on the part of publishers, precisely targeting (in pursuit of ad-generated revenue) receptive audiences — reinforcing their (our) confirmation biases. So before we address specific bad actors operating on such platforms, could we bring in your broader structural concern that even politically neutral tech firms often find themselves perversely incentivized to assist disinformation (just like any other kind of information) in going viral?

That’s right. And to take one step back, the whole nature of these big social-media platforms did offer something relatively new under the sun — the potential for us to get our information (our news, basically) from user-generated, third-party content. Just 30 years ago, we still had a traditional one-to-many media mode, with CBS News or The New York Times deciding which stories deserved an audience of millions of people. But today, on Facebook, Twitter, Google, and many other platforms, third-party content gets primacy over content created by professional journalists. The whole economic model for these platforms works this way. Revenue-generating ads get attached. Nobody checks on the information that does get released. Bad actors can put out anything they want. And as you mentioned, the platforms have very little liability under current law.

Once upon a time, when I edited TIME magazine, I would never have even thought about releasing certain types of content that you see routinely on social media today. We only would put out fact-checked content, written and scrupulously edited by experts. But now, not only can social-media platforms get away with publishing this garbage — they actually have a strong financial incentive to make it go viral. So you don’t even need to think of these platform companies as deliberately creating disinformation. They don’t. But they do benefit by optimizing how this content circulates, and I believe we should hold them accountable for that.

Your wide-ranging professional background also provides a distinct vantage on how more deliberate disinformation projects play out. As a “communications guy” in government, for example, you received any number of unsolicited recommendations for public-messaging campaigns, especially for counter-messaging, for “hitting back” against our information-wars adversaries. You note, however, that US officials tended to prioritize the content of such messaging, but not to dwell much on who the audience of this messaging could and should be, how most effectively to reach them, how to move beyond reactive counter-messaging towards more proactive, personalized, and / or catalyzing engagements.

So I approached the State Department (and also approached this book) from a kind of anthropological perspective. I became this journalist inside the room — when for most of my career I’d been kept outside. I never got over that sensation of pinching myself and saying: “Wow, so this is how they do it in the Situation Room.” And as a writer, as a journalist, I did, as you say, gradually learn that the two-way street between media and government has a lot more bumps than either side suspected. People in the media don’t understand certain basic parts of how our government operates. People in government fail to grasp how the media operates on a pretty broad level. I mean, even back in the good old days of the Obama administration, government officials would complain about media bias. I’d say: “Yeah, reporters definitely have a bias. Their bias is to get on the front page, or on the evening news.” Most officials didn’t seem to understand that basic drive, which doesn’t involve having some ideological axe to grind.

Media consumers also often have naive ideas about how to create media. And I found government completely ill-suited to the creation of media content, even when certain individuals in government had some good ideas about what to say. First of all, nobody in government really wants to stick their head out in this way. Government officials often consider it more dangerous to act than to not act — and here, creating content counts as a kind of action. When I first came into government, the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC), the first anti-ISIS entity in our administration, reported up to me. And at that time, in 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped two hundred girls in Chibok Nigeria, and CSCC’s head came to me and asked: “How about if we create a banner criticizing this despicable kidnapping of these girls?” I said: “Of course. Great. Let’s do that.”

I didn’t think about the next step much, because I just assumed that within, I don’t know, an hour, this message would go out. But literally 10 days later CSCC’s head came back and said: “I need your help.” I asked “On what?” He said: “Well, I couldn’t get that banner about the two hundred girls through the State Department clearance process.” And I won’t even go into all the details about this arcane clearance process. Suffice it to say that every single bureau at State basically has to clear anything public that any other bureau does.

While throughout your book we see ISIS, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump outflanking typical diplomatic operations — all recognizing that (again especially in a liberal-democratic context) policy forever plays catch-up to messaging, rather than the other way around.

Right, and of course the media did at one time pay a tremendous amount of attention to any statement any ambassador might make. But in 2015, when somebody at State would get extra nervous about some relatively obscure policy statement, and really examine it with a fine-toothed comb, I’d ask: “Do you really think any American media outlet pays any attention to what our ambassadors in Nigeria or Brazil say?” Alongside the reluctance to even communicate at all, you would at times get this exaggerated expectation for a big media (and broader public) response.

So here again your book’s potentially critical or diagnostic or prescriptive approach to State Department institutional culture stands out. So let’s say that State’s at times bureaucratic, careerist, intellectually siloed, administratively territorial, structurally nay-saying, temperamentally risk-averse, unreflectively spendthrift tendencies merit the “opposite of entrepreneurial” tag that this book provides. To what extent do you see Information Wars offering a real-time record of you learning State is this way (and maybe, sometimes, why State should be this way)? And to what extent do you see the book offering a pointed recommendation for what needs to change? Given, say, your sense that “the overwhelming number of people in government are there for the right reasons,” and that “the only people who could really fix government are those who understand it best,” what would you most like for this book to convey about State — to a broader public, to politically appointed State principals, and to career-long State staff operating independent of any one particular administration?

Well, first I should say that, compared to this chaotic Trump era, so many of those long-term structural flaws actually seem desirable [Laughter]. Though this book does operate from the basic premise that, when we do get past Donald Trump, we can’t just restore things to the way they were. We have to develop a new vision for the State Department. And some of what I say about State obviously applies to government and civil-service culture and bureaucracy much more generally. Modern diplomacy starts off as an 18th-century profession, right? We sent Benjamin Franklin to Paris, because it took a letter six months to travel from Philadelphia to Paris. We needed someone operating pretty independently on the scene, in ways we don’t today. Much of our diplomatic culture and its everyday practices arose from these technological constraints and this inability to communicate. So if you created a State Department from scratch in 2019, maybe you wouldn’t include so many ambassadors.

Here I do, as you point out, hope to offer some implicit recommendations for how to make State more efficient, more accessible, less bureaucratic. I think State’s broader clearance process, to prevent ever making mistakes, also prevents you from ever saying anything interesting. I would radically reform that. I would radically reform the process for selecting ambassadors. I would put an end to the habit, frankly, of rewarding political donors with ambassadorships — which undermines the very idea of diplomacy, when some soap-opera producer with no expertise gets the job. I also would seek to enhance some of what the State Department does quite well, especially through its soft-power international engagements, which I consider extremely beneficial both for the US and for the other countries that participate. I’d use technology and American culture and interpersonal exchanges to help spread democracy’s appeal, and to help facilitate the free flow of information both here and abroad.

So let’s say many US officials retain an old-fashioned notion of messaging as an afterthought. Let’s say such officials often possess an exaggerated sense of original content’s importance, and often underestimate the need within today’s social-media ecosystem also to channel and to curate compelling content. Let’s say America’s most effective messengers in 20th-and 21st-century information wars always have been, in fact, our soft-power media, entertainment, and commercial industries. Do you consider it more or less inevitable, in a diversified economy like our own, that many of the most talented communicators and storytellers and culture-branders get lured to New York and Los Angeles and the Bay Area — rather than to Washington? Or do you consider it a present-day crisis that more government officials don’t start from a media-savvy orientation like yours?

First I do want to say that the United States is the greatest content-creating nation in history. You could picture us as the full-on singing-and-dancing country. As a great believer in soft power, I’ve always thought of that as a tremendous asset. At State I enjoyed presenting myself as Chief Brand Officer of the United States. And I’d always think: Let’s get out of the way. Let’s show the world the exceptional content we create not just in movies and TV, but also in critical journalism. People around the world often don’t understand the US system works this way — that we criticize ourselves, and always strive to improve ourselves. So, in a perfect world, I don’t know if our government would create any content at all, more than just to say “Here’s our official policy on this topic,” and then to let our media take over from there.

Then for the especially tricky challenges of creating compelling counter-messaging, I’d also point to work by people like Daniel Kahneman on confirmation bias. This research shows how we cling to content that agrees with what we already believe, and reject content that doesn’t. And given the relative universality of this basic human bias, it can feel pretty hopeless to try to correct some distorted (or even completely falsified) story that just won’t go away. Or here I also think of the backfire effect — this idea that when you try to disabuse someone of a strongly-held belief, you actually make them hold onto that belief even more strongly. So yes, of course, on occasion in human history a clear, convincing, rational, and empirical argument has persuaded somebody to change her or his mind. But natural human impulses often take us in the opposite direction.

And then in terms of many of our most talented content-creators not going to Washington to work at State or even in the White House, I do think of that as a longer-term phenomenon. Even when I started at TIME back in the ’80s, my most talented friends didn’t come to New York to work in journalism. They went to Hollywood to write screenplays and TV shows. It does seem more or less natural for different types of media to become magnets for different types of talent — depending on what just feels like the freshest and most interesting and exciting format of the moment. Even writing a book today feels like some kind of ancient form of communication, but a wonderful one.

For one other angle then on how today’s content creators (and disseminators) might best contribute to some broader geopolitical mission: how have such internalized organizational dynamics played out within quite successful ISIS and Russian information-war campaigns? Who might be the equivalent to an Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy on their sides? What types of leeway might such figures have been granted that you might envy? Or why might ISIS and Russian disinformation campaigns have succeeded in part because they lacked some more cumbersome institutional hierarchy? Did they rely on a few innovative geniuses? Did they start with inherent structural advantages in these kinds of asymmetrical conflicts?

Okay, perfect. I’ll start with this more general unified theory I discuss in the book — that the rise of ISIS and Putin and Donald Trump came from the weaponization of grievance. ISIS wanted to make Sunni Islam great again. Putin wanted to make Russia great again, and obviously we know Trump’s slogan. And part of why each of these appeals proved so effective (in their different ways) came from tapping an unmet need that was out there.

Take, for example, ISIS’s campaign to appeal to Sunni Muslims, by far the largest group in Islam, with roughly 1.3 billion people. A tremendous amount of grievance circulates in different parts of this huge international community: a feeling that the West has undermined them, that their own leaders (governmental, religious, cultural) have undermined them. So when ISIS came along and showcased this historical idea of the caliphate, they could find a pretty big audience. No doubt many, many Muslims looked at ISIS’s intolerant practices and beheadings and violence with great distaste. But this idea of ushering in an era of Muslim glory, which we haven’t seen since the end of the Ottoman Caliphate, certainly did appeal to some people. That messaging resonated in part because ISIS could target audiences already willing to entertain those beliefs.

Putin, similarly, has remained this very, very effective messenger within Russia, with his popularity rating in the mid-’80s for years, because he preaches this equivalent idea of restoring Russian glory. I interviewed Putin in 2007, when TIME named him person of the year, where he called the Soviet Union’s dissolution the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century. And a lot of Russians look at this history that same way. So again, Putin’s internal messaging starts from this pretty receptive place.

Putin’s style of weaponizing grievance of course then dovetails with Trump’s 2016 campaign, with Trump tapping a group of especially discouraged and demoralized Americans (white and black, poor and less poor, all across the country) who feel that the 21st century has somehow left them out or left them behind — whether through automation or globalization or other cultural and technological and economic shifts. Russia’s Internet Research Agency in Saint Petersburg in fact deliberately taps this same disenchanted US audience. The Russians have worked at mobilizing internal grievance within the US for a long time, going back to the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s, and certainly during the Cold War. Trump came to this politics of grievance a bit later. But again, this appeal to grievance works particularly well when it overlaps with people’s preexisting confirmation bias, when it can speak to their personal sense of feeling left out, feeling the rest of America just ignoring them, feeling the elites looking down on them. I mean, Putin literally said during our interview that people in the US look down on Russians as though they were monkeys. That type of grievance, combined with that type of insecurity among leaders, combined with that impassioned response from their followers, creates a really noxious combination.

For ISIS, you describe it as “more of an idea than a state.” You note that its most crucial public intervention tends to happen outside of English-language conversations, as Islamic extremists seek to engage “the much larger audience of mainstream Muslims.” You cite General John Allen’s prediction that an ISIS which loses on the physical battlefield will fragment and attack on the information battlefield. And you no doubt have seen recent reports of a post-Mosul ISIS emerging as a more active player in Afghanistan and elsewhere. So to what extent do you see the surviving members (both active and dormant, official and aspirational), the organizational structure, and / or the enterprising spirit of ISIS as a persistent threat going forward?

We did have from the start this crisis of misperception about who ISIS were. People in Congress would ask me: “What is your office going to do about ISIS?” as though ISIS posed this direct existential threat to the United States. They didn’t then and they don’t now. Back then I’d respond by offering a few statistics which tended to surprise most government officials. I’d point out that ISIS created 80 percent of its content in Arabic, directed to Arab Muslim audiences in the Middle East. ISIS actually created more content in French and Russian than in English. They created English-language content mostly to scare us, and that worked pretty well, because we’re pretty willing to be scared.

And ironically, one of the reasons we militarily defeated ISIS came from ISIS aspiring to become a state. We do pretty well fighting states. We don’t do as well fighting non-state actors. So once ISIS actually had won some land in Iraq and Syria, we could fight them on the ground. If they had stayed more of a pure idea, the way Al Qaeda did, we would have had a much harder time defeating them. But now that we have defeated them on the ground, we should anticipate them becoming more of an idea — a dangerous and pernicious idea, because they can weaponize the grievances of young Sunni men and women all around the world (not just in the Middle East, but in Indonesia and Malaysia and Algeria and Kashmir). ISIS still has a potent message, and we should expect them to become even more sophisticated about using that message. So yes, I don’t think we should take their recent revival lightly. I think of them as an evolving and learning machine. They’ll absorb the lessons from their defeat in Iraq and Syria, and apply those to whatever ISIS 2.0 or 3.0 becomes. That’s not a pretty prospect.

So let’s say that, in the summer of 2016, you still could foresee a new Global Engagement Center fighting a broader array of disinformation-peddling rivals. Then Donald Trump gets elected. And now let’s say that a more coherent, more functional administration comes out of the 2020 election. What particular information-warfare advantages would the US have lost over the past four years? What first steps should such an administration take to regain the momentum both on winning the technological / strategic battle, and on winning the broader ideas-based argument?

Any new administration will first need to ensure the security of American elections — the primary way by which America guarantees all the other rights of its citizens. If this security gets threatened, that undermines every other choice we make.

And then, though our government does not do very good messaging and certainly not counter-messaging, it does do pretty well with analysis and observation. So I’d like to see the Global Engagement Center get as detailed and even scientific as possible about what kinds of disinformation reach which Americans, from where, and how — because we saw in 2016 the platform companies fail at finding and rooting out disinformation, in part just because Russian trolls masqueraded as Americans. They bought time on American servers, and left no easy way (particularly if you didn’t suspect anything) to tell whether a middle-aged housewife from Tennessee in fact was a young male Russian troll working in Saint Petersburg. So here the GEC could use all of our data and analytical tools to track disinformation and alert platform companies and alert regular users.

But I also think we all need to get much, much more vigilant about sussing out disinformation. I describe us having not a fake-news problem, but a media-literacy problem. People often just can’t (or don’t) figure out the provenance of the information they absorb. Our government could at least start to figure out the provenance of this information, and especially of disinformation. But what I wouldn’t have the government do is create its own information to counter that disinformation.

For a few proactive policy steps we should take against today’s disinformation campaigns, could you describe some State-specific tactics you might advocate (such as creating space for alternate political viewpoints in Russian-language media environments), some broader governmental reforms (such as modifying section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act), and / or some society-wide discussions we need to have as we seek to define good-faith corporate and individual-citizen practices on today’s social-media platforms?

So our primal sin, like so many sins, was a sin of omission, not commission. Most people, in 1996, just didn’t see the consequences of not treating these new platforms as publishers. So even before the birth of Facebook, the Communications Decency Act enshrined this very lenient arrangement — which means we now need some legislative fixes that give these platform companies more liability for the content they publish. We need to recognize these companies not just as publishers, but as the biggest publishers in history. This legal reform won’t solve our problems, but it will take us a few steps closer to solving them. Our laws will need to recognize a different kind of publishing here (the publishing of third-party content), so that we don’t hold these companies as liable for every word or image as we hold TIME or some TV network. But we do have to hold them more liable for dangerous speech, violent speech, hate speech. They can have their own constitutions and their own terms-of-service agreements. But the basic legal framework needs tightening, and the platform companies understand that. At this point they expect it.

Again the role of advertising also plays an important part. Once upon a time, when companies advertised, they bought brands, they bought space in TIME or The New Yorker or The Economist. They could anticipate the reach of this audience, and the kinds of content and other ads they would appear beside. They could expect fact-checked, reliable content — something children could read, even if the kids couldn’t fully understand it. But with digital advertising’s rise, and with much of this content-ad arrangement now automated, you might want to sell sneakers, and try to reach men between 16 and 24 in the Bay Area, and pay for an ad to appear alongside content this audience will look at, and end up associated with pornography or junk news or conspiracy theories or worse.

During the 2016 election, we had those Macedonian teenagers who created fake Hillary Clinton sites and Donald Trump sites, then realized how much more virality they received for the Trump sites, and how they could make a lot of money by just creating all this false content and getting rewarded with ad revenue. We really need new statutes requiring the platforms to take down that kind of verifiably false content. The First Amendment, bless its heart, protects content created in good faith. But in this age of social media, I don’t think we need to protect so much false hate-mongering content and dangerously weaponized grievance. So, for example, with that digitally altered video of Nancy Pelosi that went viral: Facebook should have immediately removed that false content, and should have faced the legal requirement to do so. Of course they don’t want to take on the significant responsibility of making these types of editorial decisions. So we should have a law requiring this action — also so that they can remove this kind of especially controversial content without any compunction.

That seems especially timely with video manipulations getting so convincing so fast, and with any self-respecting media troll of course tracking those developments.

Right, this big new problem will come on us real soon. Artificial intelligence and machine learning will create video that looks absolutely real. And by the way, we have a very striking example already. You can call it The Lion King [Laughter]. That’s a deepfake par excellence. But of course these deepfakes won’t stay so benign for long. When you can create videos seeming to document Barack Obama saying something racist against white people, or Joe Biden basically having his own Access Hollywood moment, that gets very dangerous very fast. As Mark Twain said: “It’s easier to fool people than to convince them that they have been fooled.”

Finally then, given these endless new problems to address, and though much of this book focuses on how your preceding media career gives you a canny perspective on government inefficiencies and insufficiencies, how has working in government also bolstered or refined or redirected your sense of the personal, social, and even intellectual value of fulfilling a public mission like this one you undertook upon President Obama’s request? And why might you consider it crucial for other seasoned government outsiders to (at times, at least) do the same?

When I edited TIME, I campaigned for us to do an annual issue about national service, exploring the idea that everybody should do some sort of year of service after high school — some kind of public service or military service. And I’ve always considered it unique (and even exceptional) about the American experiment that the framers had this idea of citizen legislators. They never wanted some kind of permanent government or civil-service class. They wanted doctors or farmers or merchants to come into government to serve the public for a few years, and then to go back to their regular lives. I think of that as unique to America. I sometimes might look on with envy at the more permanent civil-service class in a country like France, where that class has all of these impressive experts. But I haven’t given up on this idea of more Americans coming into some kind of public service temporarily, both to benefit our government’s functioning and to benefit society when they go back out.

So, as you know, this book is critical sometimes of the State Department and of our Foreign Service, but I absolutely loved what I did, and just getting the chance to work at State. I found the whole experience really moving. I still think of it as “standing behind the flag,” even if sometimes that flag doesn’t stand for all the things you want it to stand for, and even when our country fails to do the right thing. Our government could work more efficiently, and could resonate more with its citizens and with people around the world. And our government might not always do the best job of telling its own story, and of showing how its work benefits our people. But we ourselves all could benefit by taking part in that process first-hand.