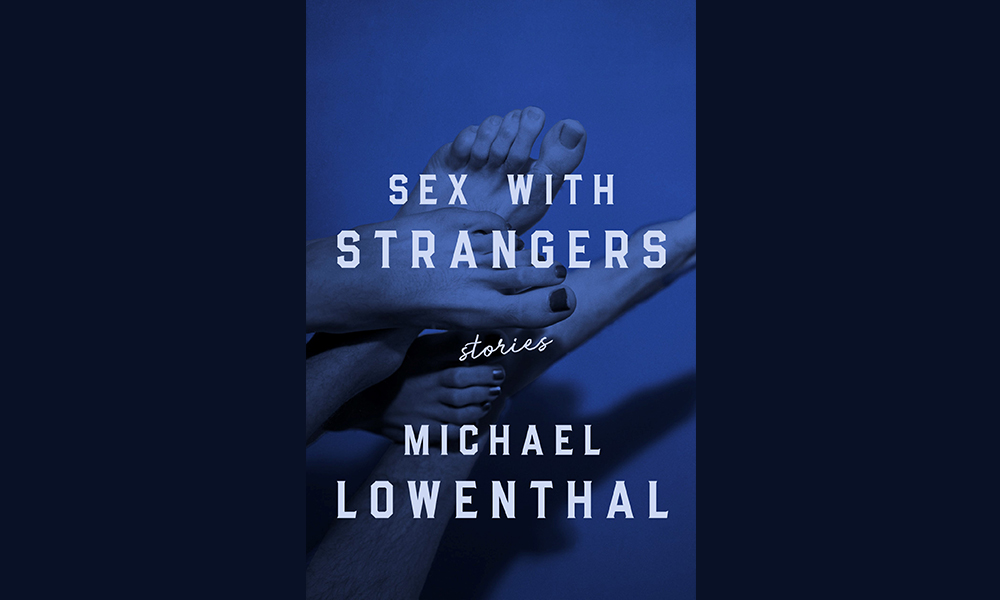

Michael Lowenthal’s fifth book and first story collection, Sex with Strangers (University of Wisconsin Press) is a book of clever misdirections. His characters often reveal themselves to be far different than who they think they are. From cruise-boat priests to aid workers to single mothers, Lowenthal’s characters meditate on what it means to be fulfilled when life throws one curveball after another. If there’s a common thread that runs through the eight stories in Sex with Strangers besides Lowenthal’s keenly observant, precise prose, it’s that life never goes according to plan.

Lowenthal was my mentor for a semester at Lesley University’s MFA in Creative Writing Program, where he continues to teach. We caught up via email to talk about his new book and discussed a variety of topics including global inequality, the nature of disappointment, and the evolution of the gay rights movement over the past several decades.

¤

LELAND CHEUK: What I loved most about Sex with Strangers is that the title pleasantly misleads. Traditionally, we think of cruising or casual sex as transgressive, but in these stories, the actual sex with strangers is usually the least transgressive thing that happens. I think of “Thieves,” which was originally published in Guernica, in which there’s an encounter between an American traveler and a local in Brazil that doesn’t pivot on the sex itself, but something much more sinister: global inequality. What experiences, if any, sparked that story?

MICHAEL LOWENTHAL: I’m glad you appreciated the misdirection. In my experience, the physical act of sex is — with some exceptions, of course — pretty straightforward. But it’s all the stuff around and beneath sexual connections that can get tricky. By the way, I also hope the idea of strangers, as it plays out in most of these stories, is not quite what it seems.

But as for the experiences that sparked the story: I was lucky enough to be granted a residency at the Instituto Sacatar, which is on the island of Itaparica, off the coast of Bahia, Brazil. In so many ways, especially for a privileged white guy from the US, it was “paradise.” For two months, all expenses paid, I got to sit in a gorgeous studio about 50 yards from the ocean and work on a novel. Someone did my laundry. Someone cooked my meals. But just outside the gates of the residency was an area where local folks lived, many of them really struggling. Deep, persistent poverty, crack addiction. Every time I walked up the sand lane to catch a ride into town, past some of these folks — most of whom didn’t seem to have jobs or much to eat — the contrast in our situations was just so startling. I was trying to improve my Portuguese, and I occasionally stopped to chat with some of the guys, who were compellingly cocky.

When I decided to take some of these experiences and turn them into fiction, I made the American protagonist an aid worker, a professional do-gooder, to heighten the contrast. He tells himself he’s there to help improve the locals’ lot in life, but when he gets involved with an islander who then steals something from him, his own reaction forces him to face up to the question of who is really stealing what from whom. And, if I’m being honest, I guess I was also trying to reckon, and maybe I still am, with what it means as a writer to “thieve” these experiences and make a story out of them, which then gets put into a magazine and a book and advances my career.

The protagonist in “Thieves” also lies about having a wife back in America and has this interesting take on hiding his homosexuality: “This didn’t feel like closetedness, but its inverse: liberation.” What’s your view of passing in today’s more identity-forward society?

Well, first, I guess I need to acknowledge that passing is a privilege (if that’s what it is, or call it an “opportunity”?) that’s not available to everyone. Lots of people, because of their skin color or accent or gender expression or whatever, can’t choose to hide key parts of their identity. They have to bear the brunt of whatever bigotry or violence might get hurled at them.

But to the extent that I have sometimes passed as straight, usually when traveling in other countries, I’ve often — like the character in my story — found the experience exciting, a chance at temporary reinvention. Now, if you’re passing because you’re ashamed of your identity or you’re running away from your past or you’re trying not to get bashed, that’s one thing. But for me, it’s a completely different proposition, because I have no shame or guilt whatsoever about being queer. I’ve been out of the closet for 33 years! I don’t have to hide who I am. And because I’m a cis white man from the US, I don’t usually feel my safety threatened. So I can play around with letting people misread me in certain situations, which can make me feel thrillingly like a spy. It allows me to see and hear certain things that I otherwise might not.

But to talk about the idea more broadly, which is how you asked about it… I will say that even though I cut my teeth as an identity-politics activist in the late 1980s and early 90s, these days I am less and less interested in tribalism of any kind. And it’s hard to see how an obsessive focus on identity doesn’t eventually lead to tribalism. I mean, we’ve just seen the dangers of tribalism from the Trumpist end of the spectrum, but I think it can be frustrating and counterproductive from the progressive side, too. Not that I am drawing an equivalency. I’m not. But in our “identity-forward society,” as you cheekily put it, it seems like as a progressive person you’re expected to announce all your precise identity categories at every juncture. You list your pronouns, you preface every comment with, “As a blank blank blank, I feel…” In my case, it’s “As a white Jewish cis gay American writer who grew up rich in the suburbs, I…” And while, of course, I do think it’s important to own up to who we are and where we came from and how that affects our actions and beliefs, I do sometimes long to break free of all the categories. I honestly find it a relief to not identify with “my” groups. Is that because some of my identities (white, male, rich) are now seen as problematic and make me persona non grata in certain progressive discussions? Well, sure. But I find it equally relieving sometimes not to identify as queer, which is an identity that should offer me a tiny bit of progressive street cred (thank goodness). I can’t get past my hope — and maybe it’s a pollyannaish or privileged hope — that we all might sometimes step outside of our lanes, or challenge the whole concept of lanes, and just join in solidarity to do the important work we all need to do as citizens and humans.

So, to bring it back to the idea of passing, it’s not that I’m suggesting anyone should pass as something they’re not, but I think if we could all “pass” as humans — if we could occasionally identify less by our specific identity categories and more by our commonality — we might be able to heal some of the fractures in our society.

There are so many “wow” moments in the prose, particularly when it comes to the characters’ disappointments and yearnings. For example, in “Uncle Kent,” the main character describes her yearning to be a mother as “as a pressure at the back of my throat, an urge to moan, whenever I saw a child on someone’s shoulders.” In “Do Us Part,” the jilted protagonist observes that love “could not be coldly counted on an abacus; it was immeasurable, a snake gulping its tail.” In “You Are Here,” Father Tim, while counseling a couple on a cruise, observes: “To see what’s possible is sometimes worse, he thinks, than being blinkered.” Would you say that disappointment (or the different ways we deal with it) is one of the primary themes of the collection?

I do write a lot about yearning, and not just the yearning to connect with someone else sexually or romantically, but also the yearning to be someone else — which I think is often part of the fantasy of sexual connection. Like, if I could just hook up with X, or be someone that X would find attractive, then my life would be so different and so much better. When the truth, of course — and sorry to sound like a self-help fortune cookie — is the reverse: being your better self is the prerequisite to making successful intimate connections.

As for the theme of disappointment more generally… my father is always saying that an optimist is someone who believes the future is in doubt. And by that measure, I guess I’m an optimist who writes about optimistic characters: in order to yearn so strongly, they need to believe they have the power to improve their futures by fulfilling whatever it is they yearn for. But the higher the yearning, the steeper the disappointment. And I’m interested, as you said, in the different ways people respond to their failure to get what they want or what they thought they wanted. I’m drawn to moments of necessary disappointments, disappointments that — either when they happen or maybe not till much later — create the opportunity for revelation.

In “The Gift of Travel” a writer helps to take care of his terminally ill mentor, and at one point, the mentor says about the gay rights movement of the 1980s, “This is why we marched? And screamed our fucking faces off? And sat in all those nasty jail cells — this? For your right to be such boring marrieds?” That made me laugh. What are your feelings about how the gay rights movement has evolved in the past several decades?

Well, I should start by stipulating: it’s undeniably fantastic that more queer people can live freely and safely, that we can be who we want and love who we want. Queer people in America can mostly now live without fear of being fired or evicted because of our sexuality or gender identity (although of course the Supreme Court is scrambling to enshrine religious anti-queer bigotry). To have legal protections at the highest levels of the government is essential and heartening. In so many ways — legally, politically, culturally — we’ve come farther, faster, than most of us dreamed of in the 1980s.

On the other hand — and it’s hard not to sound like a crotchety old unreconstructed crank when I say this — the movement didn’t really lead where I hoped it might. I thought we were working for a revolution, you know? I thought we were fighting to dismantle certain aspects of society, not to assimilate into them. So when the movement started getting obsessed with gays in the military and then gay marriage… yeesh, it was hard for me to keep my heart in it. Now, some folks argued that winning those two mainstream-y battles would change the culture enough that other, harder changes could follow. And who knows, maybe that’s the case. But I still can’t help but feel that directing all the movement’s energy in those very normative directions may actually have made the walls harder to scale for folks who don’t buy in to the mainstream.

Now, if liberation is really about the freedom to choose your own destiny, then I have to support other people’s choices, even if they’re not the choices I would make for myself. So

if queers choose to be in traditional (whatever that means) families, then I have to support them in that choice. And if trans people want to join the service, whether because they are bloodthirsty militarists or because they need a hand up into the middle class or whatever other reason, I believe they should have that option. But that doesn’t keep me from wishing that our revolution had toppled, rather than embraced, more of the social and cultural structures that I thought we were critiquing.

The mentor in “The Gift of Travel” also talks about what made his books so successful. “What they liked was my heroes. I made them flawed, and pushed them hard, way past where they ever dreamed of going. But always — always — I gave the hero a happy ending.” Your stories definitely end on more ambiguous notes, but do you believe in happy endings?

In fiction, or in life?

Both!

I guess I’d say I believe in honest endings. Anyone who’s lived a day on earth knows that “And they all lived happily ever after” is dishonest. But on the flip side, there’s a kind of voguish relentless bleakness in some contemporary fiction that seems equally false (not to mention cliché).

I think we often misunderstand what would constitute a happy outcome, and so the category of “happy ending” is thought of too narrowly. In the story you’re asking about (warning: spoiler), the narrator thinks he wants to salvage a relationship with his boyfriend, and he’s working hard at that, and he believes that if the relationship fails, he’ll end up unhappy. But then the story’s climax is his realization that his route to happiness may take a different path than the one he’s been desperately trying to stick to. It might cause pain, both for himself and for the boyfriend he’s been trying to stay with. So the ending isn’t all puppies and rainbows, but it points toward a kind of discovery and self-truth — and I’d like to think that that qualifies as a kind of honesty, which should be cause for happiness. And that’s the note I wanted the collection to end on.

In life… well, I would say I’m as happy now as I’ve ever been. And although I hope I’m not quite yet at my own ending, I guess my own experience makes me believe in happy endings.

¤

Leland Cheuk is an award-winning author of three books of fiction, most recently No Good Very Bad Asian (2019). Cheuk’s work has appeared in publications such as NPR, The Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, and Salon, among other outlets. He lives in Brooklyn.