There are weeks in which decades happen, and there are events which render obsolete the conversations which preceded them. On COVID-19, Justin E. H. Smith writes in The Point of death and curtailed discourses, finding nonetheless that “there is liberation in this suspension of more or less everything. In spite of it all, we are free now.”

In February I interviewed leading Fontana scholar Luca Massimo Barbero, curator of Lucio Fontana: Walking the Space: Spatial Environments, 1948 – 1968, a comprehensive exhibition of Lucio Fontana’s lesser known installation work at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles. The show was set to last until April 12, but the gallery is now closed until further notice, with the exhibition having run half of its assigned time. In galleries and museums across the world, in-person experiences have been suspended as a measure to curtail the pandemic. The art world thinks of itself, for better or worse, as a refuge in times of uncertainty, and many such refuges are currently closed to the public, visual tours and high-def documentation notwithstanding. As a direct consequence of these closures, the economic ruin of untold numbers of art workers and small institutions will be felt long after the end of the present crisis. In the face of mass deaths and economic immiseration, art historical questions can seem quaint, while presentist evocations of creative reconstruction gain in vigor.

Lucio Fontana with works from the ‘Quanta’ series

1959

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana by SIAE 2019

Courtesy Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milano

It is art historical questions which first agitated me after seeing Walking the Space. Across nine recreated installations, Walking the Space made the case for recognizing Lucia Fontana as an at turns under- and mis-recognized historical predecessor, especially in the United States. This is true both with regard to distinct formal terms — his neon sculptures, tele-transmission ambitions, and icky space-age chimeras predate and announce, to name a few, Dan Flavin, Nam June Paik, and, more surprisingly, Mike Kelley’s own forays into immersive installation — and to a more diffuse conceptual agenda. Some of Fontana’s most bullish predictions have yet to come to pass: in the show, a wall text quotes him announcing in 1966 the guaranteed death of easel painting; the market, who has nonetheless loved Fontana for decades now, would dare to disagree. But Fontana’s insistence on tearing out conceptual dimensions from material production, as well as his “Spatialism” — the championing of artworks capturing space, time, and all of the senses — has become a leading attitude. In highlighting the breadth and prescience of his installation work, Walking the Space centers Fontana as one of the originators and accelerators of this contemporary paradigm, highlighting lesser-known aspects of his life and work in the process, notably his range and internationalism: the show opens with his youth in Argentina, where he was born, and closes with his embrace by younger artists across the world in his later years.

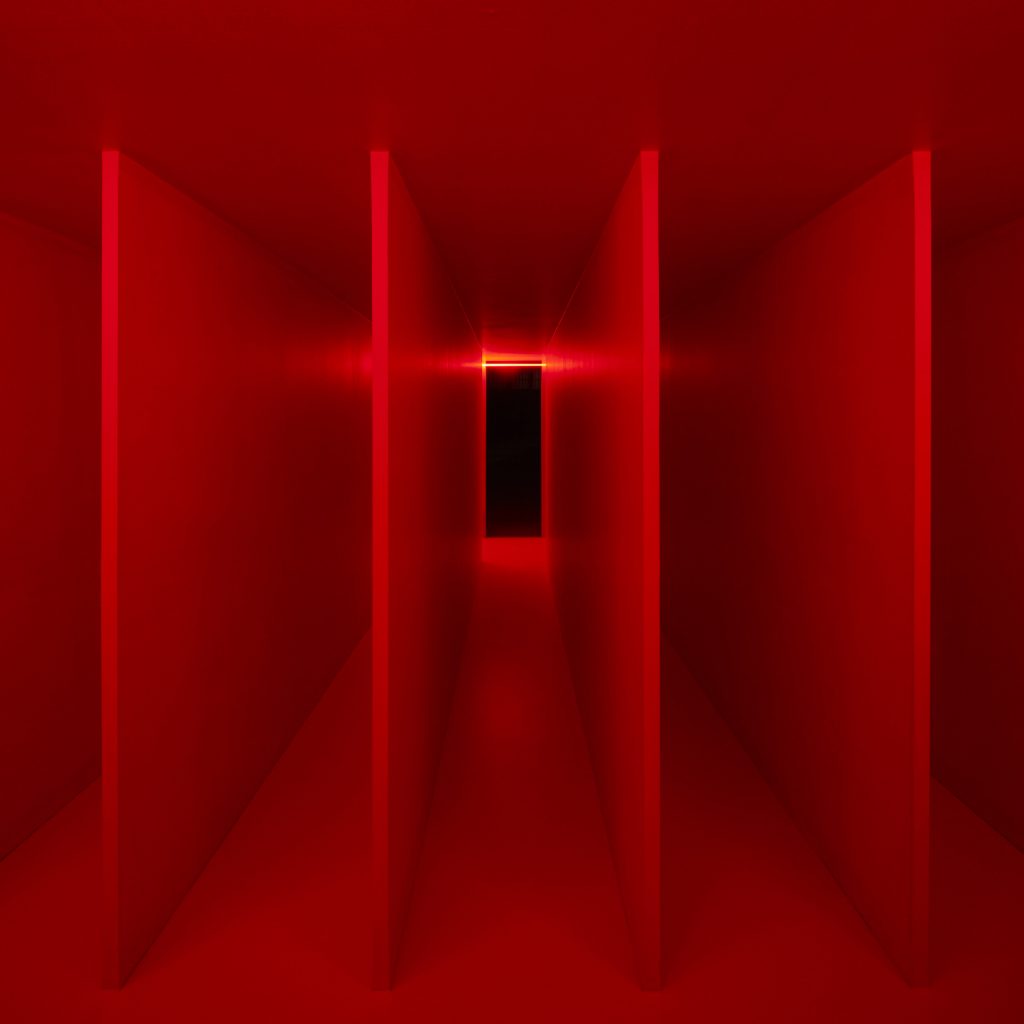

But now, more than the historical import of a show that will be seldom experienced, images resonate, some of which a virtual tour would undoubtedly fail to capture: Ambiente spaziale a luce nera (1948-1949) is a comical assemblage of floating fluorescent bodies under black light, astonishing in its colorful panache and its sweetly revolutionary pretenses. Ambiente spaziale: “Utopie,” nella XIII Triennale di Milano (1964) is a revelation, a short and low corridor lined in red carpet and lit by red neon. The subtle undulation of its floor tenderly subverts the senses, a rare optical illusion in an oeuvre uninterested with deception. The last work in the show, Ambiente spaziale in Documenta 4, a Kassel (1968) is a desolate labyrinthine landscape, ivory white, looping onto a gash in the wall, the slash displaced from its painterly support. Throughout the show, a plethora of Fontana’s exquisite drawings proves to be the main attraction: deliberate and aerial, each one a concrete scheme and a portable utopia, technological annunciations of India ink and watercolor.

One image in particular now resonates. Barbero opens the show with a 1947 photograph of Fontana stepping into the ruins of his studio, the building and its contents having been thoroughly destroyed in the bombardments of the Second World War. Captured by Tullio Farabola, the mythical picture reveals as much as it elides. Fontana was never a victim of Fascism, and his 1947 return to Milan was more of a transitional period than a breakthrough. Yet, in the context of the reconstruction to come, the image speaks. Not of the creative heroism of youth — Fontana was 48 at the time — but of the radicalism of an artist who, surveying the ruins, found the seeds needed to produce some of the most defining work of the postwar period. I discussed this image, and much more, with Barbero.

¤

ALEXANDRE SADEN: When did the preparations for this show start?

Almost two years ago. We had the original plans and maquettes for the Ambienti Spaziali (Spatial Environments), and we’ve been working since January in order to build up the space, to transform the gallery to this extent.

LUCA MASSIMO BARBERO: I am curious about the decisions that were made in terms of restaging, the most striking one being the neon piece Fontana conceived for the IX Triennale di Milano in 1951, Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano, which went from this monumental staircase to the utilitarian wood ceilings of Hauser & Wirth, which is a drastically different environment in terms of geometry and light. How were these decisions made?

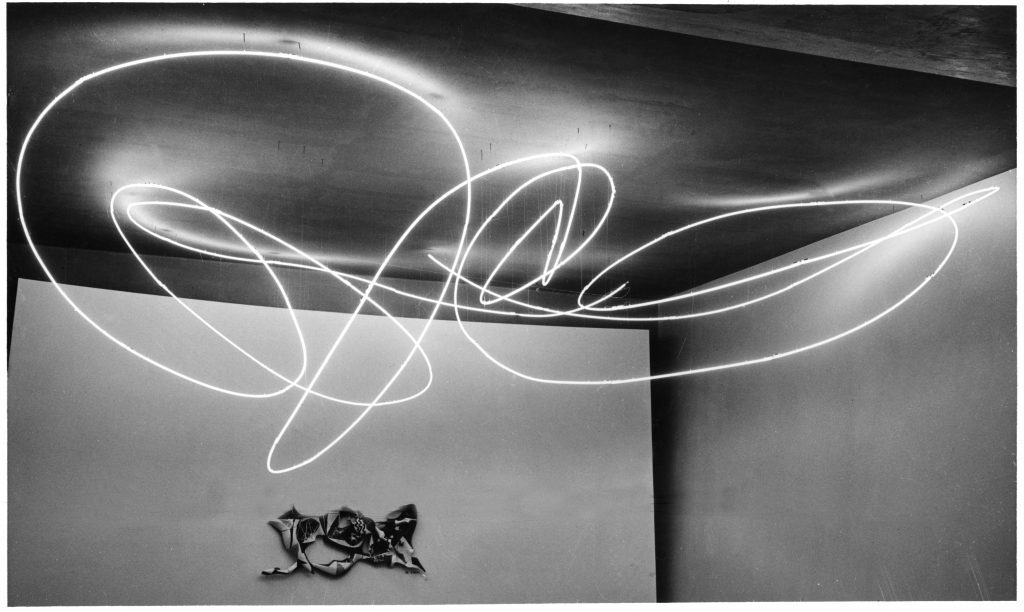

The first thing to note is that Fontana was very inventive, and Fontana was never Bauhaus-ish. He never believed in geometry as a matter of fact. Instead he believed in freedom, invention, and the idea of the gesture, so what Fontana does for the IX Triennale is really something new, radical. We needed to have that work in the show for viewers to understand how Fontana was evolving as an artist, how his interest in neon was too. He created a low-level atrium, lit from the back, and the audience would climb up the stairs to look at these arabesques floating in the sky. Fontana was really drawing in three dimensions, changing the fabric of the space itself.

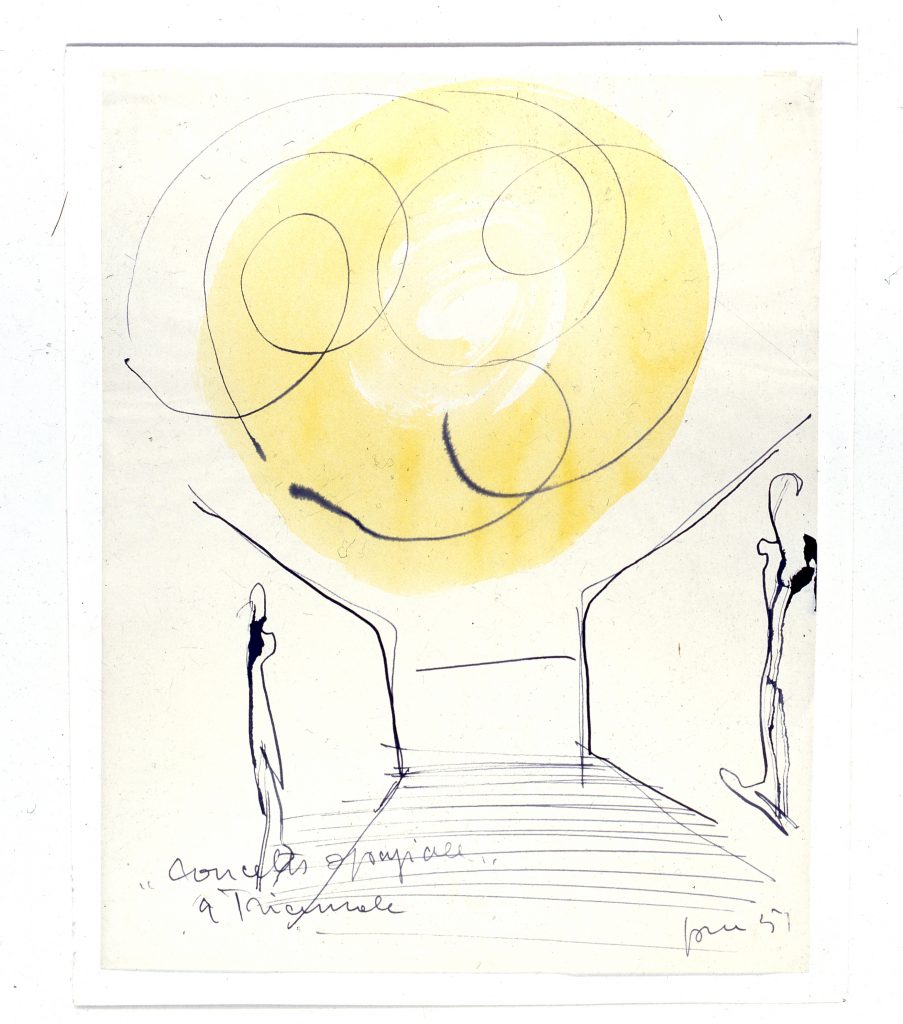

So everywhere we install this 1951 neon work, it always has to be a change brought upon the existing environment. We could have built a flat ceiling, but that’s not the way he would have wanted it. I thought, why not make the work actually pierce all those gaps between the beams? There is this enormous metallic duct there, and I refused to cover it because the reflections on the metal really highlighted this transformation. It’s interesting to see how energetic Fontana’s gesture in 1951 still is, and how the current environment highlights all the knots you have within the neon. There is a drawing Fontana made in 1952, a year later, that showcases the gestural qualities of the neon, but underneath there are only people walking and a small door with curtains, which is exactly what we ended up with in the gallery. I think Fontana would be happy with this outcome.

Lucio Fontana

Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano [Neon Structure for the 9th Milan Triennale]

1951

Ink and watercolor on paper

29 x 23 cm / 11 ½ x 9 in

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana by SIAE 2020

Courtesy Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milano

Lucio Fontana

Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano [Neon Structure for the 9th Milan Triennale]

1951

White neon crystal tubes

Environmental size

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana by SIAE 2020

Courtesy Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milano

Most pieces in the show were recreated, as Fontana destroyed his spatial environments right after their exhibition. I’m curious about the challenge of working from the surviving documentation, but also in what it means as a curator to try to revive pieces that were meant to have a limited lifespan.

There is a reason why all these pieces were destroyed, which is that they didn’t have any commercial value. They still don’t. When Hauser & Wirth asked the Fontana Foundation and I to do a trilogy of shows, we thought that Los Angeles would be the right place to recreate these works, with the context of California: the light, the immersive art.

As an art historian, I am always saying that philology is very important, which is why I like the idea of showing Fontana’s historical progression from 1947 onwards. But our goal here is not to only compile tomes, our goal is to make cradles. One of the big tasks is, and that tells you a lot about our time in which technology moves so fast and gets old even faster, to recreate Fontana’s mediums. Think, for instance, of what happened to Dan Flavin’s medium. Now, to conserve his work, you have to do neon like it was done at the time, by hand. Fontana used technologies of the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, so we had to make neon like in 1951, to use wood like it would be used in 1949.

To reproduce the works, we worked for years on dimensions and reconstruction methods, but there is a certain level, once you have everything mapped out, where it has to come out feeling like a work of the present. I don’t want the audience to feel that they are walking into a historical reconstruction; I want them to experience walking into the space, and that’s why we sometimes diverge from history, to try to match Fontana’s use of colors and lines with regards to the space.

Fontana never had this attitude of: “There is only one original thing.” For Ambiente spaziale in Documenta 4, a Kassel (1968), he had designed and casted two slashes, in order to have a replacement if needed, before the work was even installed. There are even two versions of Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano actually, a smaller version, and a larger one that Fontana also left a maquette for. What mattered to him was never the integrity of the object; it was the integrity of the idea. He stressed a lot the fact that the work of art could and would be destroyed. He focused on the idea because that is what he thought was going to last. We are really working with an original work every time we recreate it.

I enjoy the non-commercialism of these works, this refusal of the monetary value of the art object, but I am intrigued by how that interaction takes place in a commercial gallery. How did that negotiation go between your work as a curator and Hauser & Wirth, which obviously has a commercial interest in Fontana’s work as a whole, if not in these specific works?

I don’t often work with commercial galleries. I am the scientific consultant for the Fontana Foundation and have been studying Fontana for a while, but the reason why I said yes when I was invited by Hauser & Wirth and the Foundation to curate the show was the fact that they were very aware of who they are — a commercial gallery — but that nonetheless they were interested in bringing something new and noncommercial to the space, and that is the core of these works. Eventually we all have a job to do, but it’s rare that a gallery accepts a show with nothing to sell in it, even though I think in the long term it’s good for their health.

I have been in this gallery for a while now, and it’s so interesting to see how mixed the public is, which is still too rare. On Sundays there are families, art-world people, people just coming here to spend time, and I think the show provides a moment for anybody to think about what was going on art-wise at that time. My intention was not to curate a historical show, which only tells you what happened, but to give spaces that anyone can walk through, and maybe they get home and think: “Wow, that was very curious.” In a sense, that’s what we have to do everywhere: to foster a sense of curiosity while also providing knowledge. When the catalog is going to be out, we will have a document of a very Los Angeles Fontana experience that will never be repeated anywhere else, because the next time we will rebuild it will be a different environment, a different audience, a different experience.

One of the most fascinating things about the show is the implied art historical relationships it creates with more recent artists, notably in Los Angeles. Dan Flavin, of course, but I also thought of Mike Kelley in a couple of instances, with the caves and the lights, and I hope that one of the results of the show will be to insert Fontana into more of these historical conversations, especially when it comes to American artists.

I hope this show emphasizes that Fontana was a migrant, like we all are. He was born in Argentina, he eventually settled in Italy, he travelled and showed around the world when he was in his sixties, and he was beloved by new generations of artists internationally. This was an important second step, because there is no Fontana without the new generations of the ‘60s, without Group Zero, Azimuth, Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein. They all loved him. There’s a nice interview where Fontana says, “Oh, Yves Klein, when I was in Paris he would always come to the Gare de Lyon to pick me up with Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani.” The interesting thing is that we can’t really have the same relationships between artists nowadays, because there is this dominance of the market as the primary relationship.

At the time the market didn’t dominate yet, what mattered was ideas, and a relationship towards or against the establishment. In 1964, Fontana wasn’t invited to Kassel’s Documenta, so the Zero Group, instead of showing their works, staged a room in homage to Fontana in order to protest his non-invitation. They were projecting on the wall one of Fontana’s slashes, and they had discussions, events, poetry readings. At that moment, the people that we now think were ahead of their time were saying that Fontana was ahead. And then something happened, and we went back to this reductive Europe/America dichotomy. Even in the United States you had this West Coast/East Coast divide. People are always trying to divide artists, but nowadays artists are working without boundaries and that’s important. What I love about LA is that ideally everybody grows up in a mixed environment. We have to constantly insist on the idea that art can be a place for everybody, no matter who they are or where they come from.

Lucio Fontana

Ambiente spaziale a luce nera [Spatial Environment in Black Light]

1948 – 1949

Installation view, Museo d’Arte Mendrisio, 2008

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana by SIAE 2020

Photo: Stefano Spinelli

It is interesting to see how radical some of Fontana’s program still is, in terms of rejecting traditional forms. I am curious as to what you see as the place of such a program in the current moment, when there is a return to painting, to objects, to tradition in some ways.

There is this nice sentence that Fontana said, which is really important for me and for the attitude I have towards this kind of work, and you have to think of in the context of a gallery in Milan in 1949: “Finally I was free of little sculptures, something to sell, something to hang.” That was a scandal at the time, because it was the first show with nothing to sell! Of course, Fontana was doing sculptures, he was doing everything, but he wanted to face his public in order to give them an experience, not just an object.

I am not saying that Fontana wasn’t selling anything or trying not to. Fontana was always doing so-called paintings. Of course, he wasn’t selling a lot. He had a very hard time selling anything until the late 1950s. Mainly there were two types of people that supported him throughout the 1940s and the 1950s: architects, and very avant-garde collectors. He had the chance in 1947 to meet this visionary gallerist called Carlo Cardazzo, who is almost unknown to the broader public. He was a collector in the 1930s, in 1942 he opened a gallery in Venice designed by Carlos Scarpa, and immediately after the war, in 1946, he opened a gallery in Milan and one in Rome, connecting with Paris, London, and in the 1950s New York with Castelli. He died young in 1963. When Cardazzo and Fontana met, they invented something that didn’t exist at that time, which is the combination of shocking exhibitions, publications, magazines, and also gadgets. They were selling the architecture magazine Domus in the gallery even though none of the art was for sale.

When Fontana says, for instance, that the easel painting is dead, what he really means is that anything which only stays on the surface is gone. You have to remember that he started piercing the surface of the canvas the same year that he conceived the Ambiente, in 1948. Fontana is not destroying then — he is creating a new conceptual dimension. Fontana thought that we are all making objects, because in the end we need an object to anchor the idea in matter. But the idea itself is freed from matter, because the idea lasts longer than the object.

The idea transcends the object, which is its necessary support?

Something like that. When Fontana declares the death of the easel painting, what he is saying is that there are no longer two-dimensional viewers. If you think about the only artist who could challenge Fontana historically on that point, and who is so important here in the United States, think about what Pollock was doing in 1948. He was putting paint on a two-dimensional surface, while also trying to find a new way of painting. Fontana went through the canvas. These two personalities, Pollock and Fontana, transformed the idea of painting in radically different directions. Fontana’s emphasis was on the use of four dimensions, on bringing sculptural and conceptual dimensions into painting. Fontana is using the idea of painting, but to bring it somewhere else.

What was difficult for an international public is that Fontana is not easy to label through his mediums. And, of course, the difference between Fontana and the new 1940s generation of painters such as Pollock is that Fontana was already in his fifties at the time. There’s a nice sentence of him saying: “I believe in Van Gogh, color, light. I believe in Boccioni, plastic dynamism. I believe in Kandinsky, concrete abstractism. I believe in spatiality, time-space.” When you hear this, and you look at the work as an ensemble, then you understand what he was thinking: he works from the energy and thoughts of the early avant-garde, not the one of the 1940s. He is continuing an earlier tradition.

Little by little, thanks to these shows, we’re going to present the complete mosaic of Fontana’s work, and eventually there will be a broader figure emerging. It’s rebuilding a universe and giving the idea of how alive this work still is.

This show already expands the understanding of Fontana’s contributions. I think in many places Fontana is still “the artist who does slashes,” which is of course quite a restrictive view of his work regardless of the conceptual understanding of that gesture.

They needed something in order to pin his practice down. The slash is a gesture, it’s pure, it’s monochromatic, and it’s understood as minimal, which is of course not true. On one hand, Fontana was very ironic. You can tell he was having fun: “Okay, let’s install these gestures in the sky, and then maybe we can broadcast it through TV.” Which is an incredible story, really. He was broadcasting artworks through TV in 1952, years before Nam June Paik’s work. In the first room of the show, there’s this drawing of a colored circle with a man underneath, and it says: “This is an Ambiente to be broadcast through television.” It’s from 1949. And the Ambiente itself looks exactly like Olafur Eliasson’s installation at the Tate in 2003.

Of course, at the time Fontana didn’t have that technology. It was a naive technology, and I believe that makes it more radical. On the other hand, his work was philosophical, even if it was very simple in a way. He wasn’t an intellectual. It was a long route, and finally when he is in his sixties he ends up with the slashes and he has this really clarifying explanation: “My slashes are above all a philosophical statement, an act of faith in the infinite, an affirmation of spirituality. When I sit down in front of my slashes, I feel like a man liberated from enslavement to the material, a man who belongs to the grandeur of the present and the future.”

Lucio Fontana

Ambiente spaziale a luce rossa [Spatial Environment in Red Light]

1967

Installation view, ‘Lucio Fontana. Ambienti/Environments’, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana by SIAE 2020

Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan

Photo: Agostino Osio

Fontana also seem to never use memories — there is never the presence of past events within his objects.

Fontana is future oriented. He famously said: “I believe in the intelligence of the humankind.” But his view of the future is more complicated than that. In 1951, Fontana was invited to have a talk with Max Bill and Le Corbusier about the future of Earth. He made a sketch specifically for the panel, which has never been published before. The sketch says: “Men will end up destroying nature and the Earth with their horrible architecture, and they should be very worried about what they are doing. They will be obliged to fly away from the Earth in order to see it. And they will be obliged to build subterranean cities.” And underneath you have this drawing of underground cities, centers for living under the surface of the Earth. This is Fontana’s vision of the future. It is a warning. He believed in technology, but he was also warning humanity to be careful not to destroy the earth with it.

The fact is, Fontana was a very simple person, an intuitive but great thinker, who deeply understood material questions. Technology is important, it is wonderful, let’s transmit works of art through radars and television, but first of all let’s be careful. If it is materially built in the wrong way, it will destroy the planet. There’s a respect for the power of technology there, and that’s a really important thing. It is what we are talking about now.

There is this prevalence of drawings and sketches throughout the show, which help contextualize the conception of each work but also function solidly as artworks on their own. I couldn’t help but wonder if some of them were meant for collectors.

All the sketches in the show belong to the Foundation, they’re not for sale. I was educated as an art historian, but a professor told me: “You have to meet living artists, and you have to know how they are working.” At that time, I was living doing photography, so I started to meet artists in order to take portraits of them, to look at their work, and in the process I fell in love with works on paper. There is this moment when you study an artist without knowing them personally, just through their sketches, where you understand the specific circuitry between their mind and their hand, the speed of their ideas and how they are translated onto paper.

I have been studying Fontana’s drawings for many years, and I ended up publishing the Catalogue Raisonné of his works on paper. What I found out was that Fontana was the fastest one. He was putting thoughts down almost instantaneously on the page. And they were never technical, they were never done for sale, you can tell he wasn’t drawing preciously or like he was doing homework. Instead, his drawings are fundamental; they already contain everything needed to start the making of the work.

What you have in this show is nothing compared to the complete works on paper. There are 6,000 of them: Fontana’s whole laboratory is there. You have these little sketches made in the 1950s, with some dots, some double and triple Xs, maybe six or seven of them all grouped on one page. Some of them have “Va Bene” (All Right) written underneath. And if they do, it means you will find the corresponding painting, and it will be exactly like that sketch, which means that Fontana wasn’t painting intuitively at all. He was painting and piercing very carefully, following preparatory drawings. Even if in some videos he would use these fast and exaggerated gestures, it was always prepared. What was primary was the concept.

The image you open the show with — Fontana in the ruins of his studio — really struck me. It is an image so grounded in the politics of its time, whereas the rest of Fontana’s practice was significantly less overtly political than many of the artists who came after him. What can you say about the politics, or lack thereof, of Fontana’s practice in the 1950s and 1960s?

I open the show with the photo of Fontana in the ruins of his studio, because it’s really important to understand how Europe was in the ‘40s, how Italy was. After Fascism and after the bombings, Milan was thoroughly destroyed. It is important to understand the immense energy that artists had to give for the creative rebirth of cities and of the nation, so it’s very interesting to me that for the 2013 Venice Biennale artist Alfredo Jaar used that same photo in his work for the Chilean Pavilion, in order to show his belief in the resistance of contemporary art, in what art can do. Jaar said: “For me it stands as an image of resistance, of what art and culture can do in a society.”

But we have to be honest: Fontana wasn’t thinking much about this Earth. In that sense, he wasn’t really invested in politics. Fontana was really interested in the human being, so when he had the chance to come back to Italy after World War II, his main concern was to participate in the remaking of the universe. He was thinking on a universal scale, attempting to create a better world.