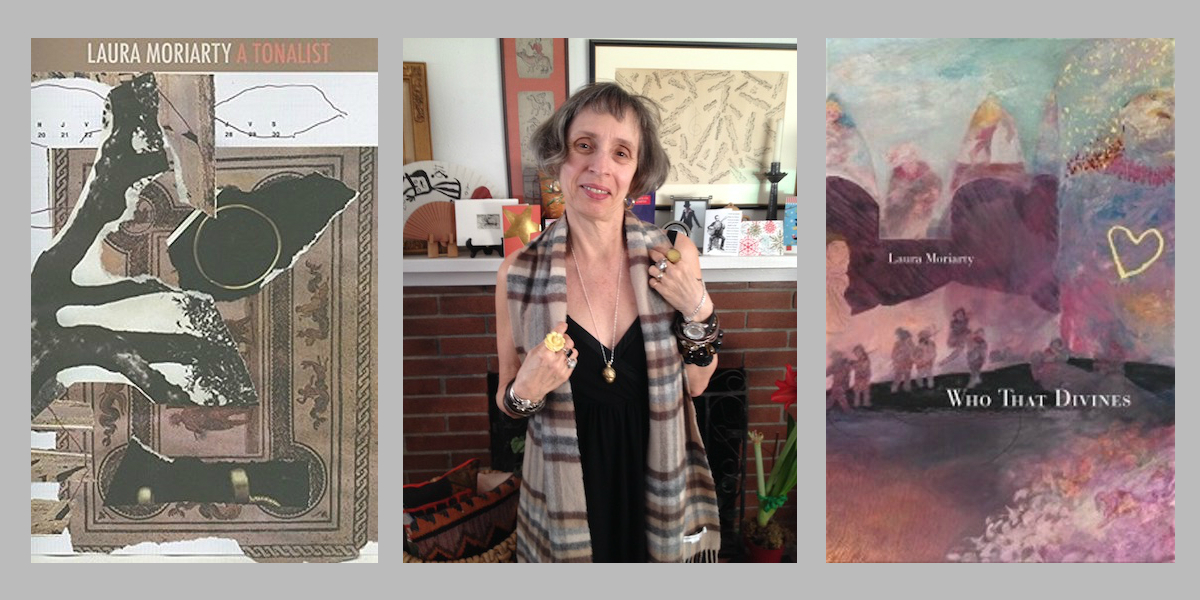

How might cataloging thousands of new poetry publications each year shape your own lyric/post-lyric interventions? How might decades of intimate personal relationships across sometimes combative Bay Area writing communities contribute to the same? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Laura Moriarty. This conversation, transcribed by Maia Spotts, focuses on Moriarty’s book-length essay A Tonalist and her subsequent collection Who that Divines. Additional recent books by Moriarty include: Verne and Lemurian Objects (Mindmade Books), The Fugitive Notebook (Couch Press), A Semblance: Selected and New Poems, 1975-2007 (Omnidawn), and the novel Ultravioleta (Atelos). Personal Volcano is forthcoming from Nightboat in 2019. Amid her refractive reconfigurations of turn-of-the-20th-century California Tonalism, her heterogeneous friendships and literary affinities, her excursions into noir detective fiction, her past work at the San Francisco Poetry Center Archive and current work as Deputy Director of Small Press Distribution, and her ongoing explorations of the Cascade Volcanoes, Moriarty has cultivated an acute appraiser’s eye and ear for many of the West Coast’s most exquisite and most combustible topographies. Moriarty’s A Tonalist and Who that Divines meld those multitudes. Her introspective, elastic, exploratory conversational mode does the same.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Recognizing A Tonalist as a potential fiction from the start, could we nonetheless approach it from a variety of angles? Before attempting anything like a definition, or explaining why efforts at definition might inevitably fail, could we consider artistic precedents, both in painting and music? Your references to California Gothic as precursor to a cinema-noir aesthetic, your references to Schoenberg, to Cage, give A Tonalist specific regional focus. Whistler’s presence expands the geographical scope in some ways. But Whistler’s A Tonal status always seems somewhat suspect, pointing my question in other directions. For instance, your references to male precedent, to men, interest me as this book, and certainly as Who that Divines, push A Tonalist aesthetics towards feminist praxis. But to begin with, if you had to describe A Tonalist in relation to painting, to music, how would you do so?

LAURA MORIARTY: It very much starts from that point of view. And I’ll say that A Tonalist doesn’t mind being codified and recodified and over-codified. It’s just the nature of using a description like that, which offers an “ism.” And an “ism” is by definition what one studied in Art History 101 or whatever. I long have had a fascination with California Tonalism — the work of Xavier Martinez, and certain other people, which mostly has not had its day. Every now and then there’ll be a show of it. A focus on what didn’t make it.

What made it was Impressionism. And what came out of Impressionism…that’s our narrative. From Impressionism, post-Impressionism, Picasso, abstraction. There’s a march down the 20th century, and, in that march, Tonalism really gets left in a 19th-century backwater of moonlights and dark painting that is lyrical, and lyrical always means pink — it’s like I’m describing pink. It’s feminine as opposed to scientific. It’s in that dark category. Aesthetically it pleases me. I like the darkness. I like the transcendental idea of it, which is so anathema to the way of thinking when I came up as a writer in my thirties during the 80s. Everybody was off that stuff and didn’t want anything to be spiritual or anything like.

So I was attracted to all of that as being not what was happening then, not what was happening in scholarship, really never what was happening. But then I realized that Tonalism was kind of associated with something that was too lyric in the negative sense, of being too pink, or too decorative. So then A Tonalist began to seem something to call it. And the gap between “A” and “Tonalism,” I became a little transfixed with that. This grew out from its visual aspect to include a lot of other things.

Could we then also step back and reapproach A Tonalist by offering some personal/interpersonal context? Here I think of Norma Cole’s stroke, the death of your husband Jerry, the place of both mourning and enduring in A Tonalist. And the polyphonic citational possibilities, for example in the book’s title poem, raise interesting questions about how collage and figuration might meet here. A Tonalist seems wary of classical emphases upon iconography/representation, but also to draw upon Bay Area figuration, as well as to perform an elegiac function. At the same time, A Tonalist the book states: “It is not about death, suffering or sacrifice, but about cultivation, recitation, transcription, translation, genre, gender switching, mud and light.”

I think I once commented to Norma, who I would describe as my best friend, that I really hate nostalgia. I hate sentimentality and dwelling on the past. I’ve had a lot of deaths. People have deaths. People have lives. I don’t like to get caught up in it too much and “transfixed.” At the same time I would say a lot of my work, and a lot of work that I really like reading, is elegy. And actually Kenneth Rexroth once commented that the Bay Area form is elegy. He was going to put out a Bay Area anthology of elegy. I don’t think he ever did, and I am not sure he was right, but I’m very attracted to the form.

And there’s a force for the naming, or the false naming, of this style of writing, which is that, as a young writer in the 80s, I felt that I, and my husband Jerry, occupied an odd place in between Language writing and writing that was associated with New College (with Michael Palmer), which didn’t really have a name — writing associated with Acts magazine and David Levi Strauss and Benjamin Hollander, who were its editors, and Norma Cole and others. Anyway, the Bay Area was very balkanized. People did cross lines but not often. If there was a reading by another group, you didn’t go to it. It was kind of a fierce time, as times often are in the Bay Area, or in New York, where there are so many poets that you can fight with them. I felt like I had a lot of very important relationships among Language writers. My husband, Nick Robinson, is Kit’s brother, so I’m very associated with that land of people. I know them all pretty well and have, over these 30 years, spent holidays with various folks, have gone on trips, etcetera. At the same time, I felt and I guess continue to feel that my writing has a kind of difference, and they seem to all have felt that way too.

Also, my best friend is Norma, and I’m associated with people such as Norma and Michael and Susan Gevirtz and a whole lot of other people who have a somewhat more lyric, somewhat more European, translated, French-influenced way of looking at the world. Somewhat different than the Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams sources of Language writing. But of course there’s a lot of commonality there, with people doing translations, being friends, marrying each other. To people of my age from that time, all this is pretty apparent, but I have found that to younger people it is completely obscure and nobody can trace out those differences. Anyway, basically A Tonalist or A Tonalism is experimental lyric. You can say it very simply. It’s lyric that questions lyric, as opposed to a writing that says lyric is normative, or to a kind of poetics that claims lyric can’t happen at all. That’s the simple context.

To use the collage method was entirely normal to me — I think it is very normal Bay Area. My first training in art came from an Art History teacher, John Fitzgibbon back at Sacramento State, as well as from the artist Carlos Villa and others who were there then, so I really came to writing through visual art and through a knowledge of the California scene. California figuration is something that I learned about and was looking at pictures of, and I was meeting those people before I ever wrote anything.

Also in terms of collage, Bruce Conner was important to me though I don’t think I ever met him. When I was a baby poet, like an undergraduate, that context included Robert Duncan, and the Beats, especially Diane DiPrima, Michael McClure, and Bob Kaufman, who I did know and certainly read closely back then. All of that is really foundational for me. When I was writing A Tonalist I was close with the people I wrote about, whose work is quoted as part of the book — not necessarily friends with all of them, but I admired the writing of the people whose work I called A Tonal.

So for me A Tonalism is a fiction, but at the same time it exists. I can recognize it. Brent Cunningham and I say to each other (not often anymore, but it happens) that people are A Tonalist. Standard Schaefer and I wrote an (unfinished) novel about it as a sort of cult. In the same way (as a whole other and much more recognizable discussion), the New York School dominates people from New York. They are in it. They write it. They exist through it. They are also apart from it, but it’s a part of their DNA in a certain way.

Well your differentiation between, let’s say, A Tonalist and Language poetics, which you sense might seem obscure to subsequent generations, definitely stood out to me, especially in passages such as this one: “I understand what you mean by the word hand though you haven’t said the word, but the gesture is evident. The light is stunning on the narrow bay before us. But will it stop the war?” Here the materiality of text does not stand out as prominently as does the empathic, intuitive, relational, nonverbal “gesture.” Or even amid its gender and genre fluidity, A Tonalist cultivates some sense of embodied identity, with even its “nonspecific person” still “saturated with color — with subjectivity, identity, physicality, sex, race, health, age. Rage.” Given that perhaps nonspecific but quite detailed approach to personhood, does it also make sense to discuss New Narrative here, as we continue to explore overlaps and variations in Bay Area writing?

Sure. It’s interesting, because the writing of Barrett Watten, Kit Robinson, and Lyn Hejinian, or the East Coast people like Charles Bernstein and Bruce Andrews, is very distinct (by which I mean: from each other). It’s various kinds of writing, and the commonality between, say, Kit Robinson’s and Rae Armantrout’s writing, which has a kind of lyric context, is different from that between say Barry and Ron Silliman — though I would stipulate that there is a common tone or feeling. I think the identity of a group, and the identity of a group’s style, if you dive into it, always kind of falls apart on one hand. But on the other hand, there is a style, and I do perceive connection as well as difference.

I think that if you were a woman and/or perhaps a person of color (if you were not a cis white guy) back then, you were like: OK, this writing wants to be writing that is by a fully-fledged subject…as if I was a white guy. It doesn’t want to be work by a second-class citizen of any kind at any time. Which is something that I feel is an aspect of modernism. It is as if, if we make this gesture, the grand gesture, then we aren’t gendered. We aren’t raced. We aren’t anything. But this isn’t something that I have ever embraced, and I celebrate the gender and celebrate the difference and celebrate my own particular working-class background. It is what it is. Not only am I not pretending to be something else, or desiring that other people need to be something else, but I’m all about their context, their actual being, and their physicality, and the fact that they are sick, or the fact that they’re dying, or the fact that they’ve got three kids and a job, or whatever. These things are definitive. They decide what you are going to do in your life. It’s not an even playing field. That’s always present and I always want to be seeing that.

But this doesn’t mean that people who have some kind of privileged position can’t make tremendously good writing. Sometimes it’s the thing that they are blessed to be able to do. And I don’t want this to be a position filled with resentment either. I just want to say that a lot of these differences resolve in an odd way, and the thing that you resist is the thing that you find yourself drawn to. Back then, for instance, I was not particularly a reader of Duncan. I knew him. I went to his readings and lectures. He was not an easy person to be around. And I found him to be too domineering and felt obliterated by him when I was around him, and ran the other way. And I just wasn’t buying his velvet-cape thing. Now, especially in the last 10 years, I love him. And I’ve read all of him. I find him completely useful. I feel like you follow your nose and there are a lot of resources in the writing world that are incredibly vibrant and useful.

I also don’t want to box us in too much with literary points of reference. Given, for instance, A Tonalist’s foregrounding of monochromatic ambiguity and corresponding rhetorical subtleties, complexities, I wondered about this book’s timeline of composition, presuming that it took place amid post-9/11 Bush-driven American political discourse. But then your formulation of how poets form a “generational take,” and your own personal trajectory within a military family — all of that intrigued me as well. So which historical/personal timelines seem most relevant to you on which to place A Tonalist?

That’s a really interesting question, in that I find it interesting to be my age, which is 64. I did grow up in a military family. My father was in the Air Force. He served in Vietnam when I was in high school. So my experience of Vietnam is as being a person in high school, as opposed to a person in college. People who were a little older in my generation were the people who demonstrated, but I’m younger than that. So my experience of that war was very intimate, but, beyond that, nobody else in my family has been involved in a war. I always regard people of the military, and even cops, as humans. Some of them are good — I have to say it’s harder with cops, currently. My father was not an evil person. He was a sergeant in the Air Force. He had Vietnamese friends. He had Montagnard friends and colleagues and was in a band with close friends from the Philippines. It’s a much more complicated situation than people on the far left want to imagine that it is.

But I also went through the early revolution, in a certain way. What happened in ‘68 — late 60s, early 70s — was even more intense than what happened during Occupy. So many of my young friends during Occupy really expected the world to change and for there to be a giant revolution, and I’m like: number one, if there is, you may not like it. And number two, I don’t think it’s going to happen. I always felt like an old fart when I was thinking and saying those things. It’s interesting to have that range of experience in one’s life. And I think that does form a context. There is always a political aspect to my work or at least to how I feel about it. I might not seem as determinedly political as some of my friends, though economically and class-wise I feel I am there on the barricade. One friend (I won’t name names) who was quitting a college job once said: “I’ll be caught in the net of the middle class…” As if to say “I don’t need to really worry about this.” I was like: wow, caught in the net of the middle class — what is that like? I don’t feel like I’m working with a net. I was a waitress for a long time and took a pay cut when I began working at the San Francisco State Poetry Center Archives. I was fairly poor when I was younger. Not impoverished or anything, I just come from a lower class background than most of the writers who I’m friends with.

So I feel like there’s a range of knowledge of kinds of people and kinds of wisdom and smartness and kinds of chances that I happen to have from my particular point of view. I try to include that in the work, and at the same time I am aware that there’s something about the surface of my work that means it is not going to be read by most of those people I grew up with, because it’s not really going to be that legible. But I need it to have the surface that I want. I need it to be as hard or as abstract as I want it to be, or whatever, while retaining a personal quality and a physicality — with a persona. Making that claim makes me reflect back on old ideas of writing in relation to oneself, and then finally, these days, on not thinking, as in the 80s, that autobiographical, emotional stuff is practically illegal. Back then you just couldn’t think that there was a self. And now, there’s a self. It’s different and times have changed. Perceptions have changed. Reality settled in and we realized the self existed the whole time, and it was OK.

In terms of where various selves and subject positions might manifest in A Tonalist, could we discuss some micro-details? You’ve suggested more generally how A Tonalist foregrounds tone’s presence in multiple artistic practices and intellectual disciplines (“Tone suggests musicality and can also relate to accent, emphasis, force, inflection, intonation, resonance and a range of color terms such as hue, shade, tinge, tint and value”). Here could we look at monochromatic, sometimes alliterative or assonance-heavy lines such as: “Whose robe falls / Opens the garment or form / Frames a torso that twists / As she reaches (reads) / Or pictured sitting sits / Also pictured the book”? Or I love moments when a sentence abruptly stops, as if emulating the arbitrary borders of a visual composition, as with “Where the explanation is worse than the disease we feel we remember when we.” Or collage-like descriptive compressions sometimes appear in clusters: “The days run away with your heart fixed to the bones by the sea”; “The fish turns to look back tangled his scales like leaves open out widely.” Or sometimes grammatical slips seem to blend singular subjects and plural subjects: “As parallel universe do exist.” Those localized gestures all interest me, as does the “more on that” refrain, which always seems to promise rather than definitively delivering — more suggestive than demonstrative.

It’s very interesting to hear you read from my work, because it makes me remember that the entire project of this book, in a simple way, was that I had a concept of Tonalism and then, ultimately, of A Tonalist, and the entire book is definitive. Every single line is defining what A Tonalist is. It always would surprise me to be asked what A Tonalist is — it’s so explainy. It explains in a very specific way, I think. It’s definitive by demonstration. That was, for me, a framing and a foundation.

It was an act of self-definition that I felt the need for in relation to my place in the writing world. And also in relation to my place as a person at SPD, because I think during the time when I was writing this book I was still doing a lot of the cataloguing. I don’t do that anymore. There’s other folks now at SPD who do this — who have every single book in their head. My friends Nicole Trigg, Trisha Low, and Zoe Tuck are currently doing that work. Making the records for all the new books can be quite overwhelming, because you have your little corner of the universe, and you think you know it, but there’s a whole lot out there. And SPD is just a part of what’s present in contemporary poetry publishing. So I think I needed to define myself against that, or in relation to it. But also just as a person my age, and what can I say about what I do and what my friends do.

We mentioned Jerry Estrin before. Jerry was a very troubled person in his relation to the poetry world. He felt excluded by various groups, but then that tendency to exclude and those vexed relationships attracted him. His tendency with a group was always to resist it and assault it and to do the opposite of what it wanted him to do — but at the same time to expect to be accepted and celebrated by it. He liked resistance himself and he expected other people to value resistance, which they don’t always do. It was his personality to be irascible. I valued his work a lot. We got together in our twenties and invented our ways of writing together. His writing finds itself in relation to my work and Norma’s work, or the work of others. He is part of what I eventually called A Tonalist. Making a context for his work is part of the project, part of the elegy of it.

The word “exemplary” kept coming to me as I read this book, even while I tracked, say, repeated utterances, a musicality of recurrent phrases such as “There is never any time” and “Nothing is what I wanted.” And again, both contain the potential for ambiguous, divergent readings (did the “I” specifically want nothing, or want many things and not get them?). Would you like to discuss formal, rhetorical, autobiographical resonances within those phrases? Or we could find ourselves pivoting to Who that Divines here too. One blurb, for instance, describes this latter book as “ambitious,” presumably for its bringing together of potential contradictory elements.

In my writing, I almost always intend all of the meanings of a word or phrase. And I think that’s a particular approach. I’m surprised when other people intend something very specific and narrow. I think it can be good in writing to mean one thing, but it’s not my way. At times, at a reading, a writer will spell the word out for you as if to say: I mean this word and not the other. But I always want both words.

In the current project that I’m working on I’m very much thinking about time. I think we all focus on it. It interests me from a scientific point of view and from a daily-life point of view, as someone who’s always had to work pretty much full time. I think when you are working full time, there’s some kind of shadow pull on the life that you want to be living from the life that you are living because you don’t have the time. You don’t have the time for the projects you can imagine doing. And if you have children, if you have a family life, and if you have ill family members — there are so many demands on you that aren’t the work, and yet you want to do the work. It’s vexed and hard to control for anyone. I think that aspect of time is present for me. History is also central for me, going all the way back to pre-history and into deep geological time. I tend to be aware, when I’m in a place, which Indians used to be there and who still is there. I find something like geography both cultural and physical.

The “nothing” of your question, to move on to that, is a useful segue to Who that Divines. To be biographical, I think that line in that place was about a relationship that didn’t work out, a friendship that seemed like it was going to be close and ended up being the opposite of that in some ways. There was a particular person and a particular moment in time. It also resonated back for me in terms of other relationships. But it’s also a quality of emptiness that I look for and aspire to in my work, and I look for in other’s work I enjoy. A quality of cleanness or emptying something out. It’s always something that I’ve said about what I like in poetry, and then I always wonder what I mean by that, and then I try to figure it out by doing it, and by writing about it with regard to other people.

I would also describe myself as a Buddhist. I’ve been involved with Zen for a long time, especially when my first husband was dying. That was when I first got involved with it in a practical way, because if you are a person in a lot of pain it will actually help you. I stayed involved with it. And my husband now, Nick Robinson, has a very long practice. So if I was dying in a hospital, I always say I would ask for the Buddhist. That whole huge vast concept of emptiness and nothingness which exists in Buddhism is certainly part of my way of approaching the work.

In terms of your preference for a maximalist possibility of meaning, rather than any one strict narrow meaning, A Tonalist’s evasions of phallocentric assertion pick up added traction in Who that Divines, starting from the Irigaray epigraph (“Divinity is what we need to become, free, autonomous, sovereign”) onwards. Who that Divines quickly follows up by proclaiming that “The life-and-death struggle for recognition among gendered subjects is the background of ordinary life,” or much later by citing the assertion that “‘Woman is a common noun for which no identity can be defined.’” More broadly, perhaps, Who that Divines, in A Tonalist fashion, presents gender as linguistic construct, social construct, yet also lingers upon and humanizes this construct, rather than just dismissing it. Or how would you approach the transition from one of these books to the other?

A Tonalist is basically a really long lyric essay in some way, and was very ongoing. I don’t know how many years it took, but it was written over a period that was still a little narrower and more focused than Who that Divines. I always feel like I am trying to do something entirely different with the next project, and I want to go away from whatever parameters I was just working with. And I think people sometimes feel that. But what one writes will often sound pretty similar to what one has written before. I often will have that goal and yet also the desire to be indulgent. I have something that I think I should do and then I have something that I want to do. And I want to do the thing that I want to do. I have a couple of fascinations. I have an interest in the occult. I have a connection with ideas of spirituality.

So that was part of it. When I was first working on Who that Divines it was called “Divination” and I thought of it as a rewriting of Persia, which is one of my first books. And Persia, which I wrote in the early 80s, was written in relation to Tarot cards and to Sufism. And I happened to be working in a restaurant with people from Iran — that’s partly why I called it Persia. I had not read Edward Said at the time, or I would have had the sense not to call it that. It had an occult context. And in the 80s that seemed just as illegal as having a self. I literally could have been arrested for doing that. I was really surprised that people like Ron Silliman liked it. It got an award. I was surprised that I had readers and no one objected to it. I thought I was doing something completely resistant to what I perceived as the dominant paradigm. So in a way I was letting myself rewrite that book as a much older person.

Still Who that Divines isn’t much like Persia. It was at the beginning, but then expanded into other things. There’s a lot of gamesmanship in it, a lot of word-list poems. I was asking for word lists from my friends. Even before Persia I had written a poem using words from a Bruce Conner art piece that Michael McClure had provided, made into a sort of game-board sculpture. I was inspired by Conner’s gamesmanship in that and much other work. This expanded out into a lot of poems that are based on tricks or just fun. At the beginning of the book there’s a lot of fairy tale. Also, as I began to work on it, I realized that I wanted the book to be very feminist. As a person my age (maybe it’s not true of younger women) I feel a particular danger in being feminist and in saying so. Actually I know this is true of many younger women as well. If you’re going to call yourself a feminist, people might attack you, usually men. I have been attacked (verbally) so many times in my life, and many women have, for doing that — though I think this tends to occur more if you are performing this assertiveness in some public way or if it is part of something discursive. Sometimes any feminist assertiveness seems to be experienced as assaultive and worrisome to people, well, men, who will find a way to object to it.

This desire to revisit a sort of feminist consciousness-raising, as we used to say, of my youth, and to combine it with the even stronger feeling of now, lead me somehow to Luce Irigaray. I think I read a book called The Interval that was about her. Out of all the French feminists, she was the one I had read the least. So I decided to read her, and that began informing the last section of the book and also how I put it all together. And then there are two sections in Who that Divines that Kazim Ali convinced me to include. One had been a chapbook, “An Air Force.” The other was material related to 9/11, which was written probably previous to A Tonalist, but which I had published in Leslie Scalapino’s War and Peace anthology but not in a book. Kazim convinced me that this piece related to the rest of Who that Divines, and I began to see that it did in providing a biographical context for the rest of the work. His editing was very important in terms of how the final manuscript came together.

A Tonalist cites Joseph Beuys on thought as sculpture, and your ongoing emphasis on embodied thought (potentially distinct from emphases on linguistic materiality), led me to wonder how future A Tonalist installments might echo the visual practices of écriture féminine. And for Who that Divines, when I think of thought as sculptural, I think especially of the “Departures 1-11” piece. “Departures 1-11” appears to demonstrate a commitment to micromechanisms over masternarratives (I believe you use those two terms in the project), to the “miniaturized but still cosmic in scale.” “Departures 1-11” presents this incredible density, but also a depth of breathiness in its prose, seeming to offer both an embodied resistance to and enactment of narrative (somewhat like A Tonalist takes an ambivalent position in relation to the lyric).

I have written a couple of books I call novels, and have almost an obsession with narrative. I’m basically constantly reading it as a kind of Berrigan-level novel addict. That piece “Departures” was written in relation to 9/11. Brent Cunningham and I were in Long Beach, going to a California Library Association conference. We used to do a lot of those for SPD. He started writing Bird in Forest in that convention center, and I started writing this piece back at the hotel room. Earlier we had driven down to LA to do a reading together. We had to drive because the flights were grounded. If you remember that time right after 9/11, you’re looking up at the sky and you’re like: Is something going to happen? Are people going to bomb the bridge? It was frightening and vivid and strange.

As a kid, I had lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis on an Air Force base. I lived two blocks from the big siren that used to go off. My father took off and flew planes and was gone during those periods because he was on duty. So I had a particular experience of that in the past. And I had the other context of a background of reading about Islamic art and poetry, and a desire to be aware of people as people, and an awareness of issues that people have with the U.S. as an empire and the terror that comes from that, and that causes people to take up arms against us. And how that’s sad or maybe tragic.

Brent and I were travelling to maybe six or seven trade shows a year during that period. I was a frequent flyer and I love airports. Again, I grew up in the Air Force and I can sort of recognize names of planes and I’m not afraid to be on them and I like turbulence. Airports appeal to me as little cities. Also, when you’re in an airport, you just have to sit and read because that’s all you can do. Actually that was truer then. Now you will be on your phone or searching for somewhere to charge it. But potentially you have some time to think, because you are just waiting. Brent and I traveling together was huge fun because we would have these wonderful conversations, and then he would be reading something and I would be reading something else and we would be desperately tired and I would probably have a migraine and it would just be an interesting situation. So that’s also part of it.

You also had brought up how gamesmanship plays out in Who that Divines. In terms of your writing’s relation to others’ texts, in terms of collage-like literary practices, your borrowing of limited word-sets (32 words, let’s say, from a variety of individuals) — all of that stood out. So we could consider the different palettes offered by these borrowed word-sets, how they will shade the tone of a piece in terms of content, assonance, possibility of patterned relations. We could look at the specific poem “Document,” with its description of the touch or hand that each individual writer has in shaping the world, and how you clarify and/or complicate such phenomena through your appropriations.

I like collaboration but I think it’s hard, even just in terms of, perhaps, having time to work with people. So one collaborates with them not by being in the same room and working together — which would be fun and I would like to do it, but usually can’t. It’s also usually very hard to write that way. So I would request words from friends and use them in a poem that inevitably related to the friend. I feel like we all do this to a degree. Part of the pleasure of being in a community with a lot of other writers is that you are constantly in relation to them. These kinds of collaborative gestures, which also occur in A Tonalist, celebrate the writing of people one reads and mention their work as a context for oneself.

And I like to be interrupted either in reading or in actual life. If I’m writing, I’m often listening to music at the same time. I like to feel that there’s the narrative or just the narrative of working, and then there’s the interruption from the other thing, which I’m usually cultivating in some way. And then I’m often creating a parameter for a particular work, so I’m allowing for certain kinds of interruption and not others.

What I’m doing now is not about quoting other poets. My current project is more connected to geology and other sciences. Or I might quote Isaac Newton rather than a poet. I’ve been using Verne for a section named after him. When I wrote Nude Memoir I allowed myself to write about movies. I’ve never allowed those in as much as I did in that particular book, where I was all about movies and about noir and other movie genres. And the particular poem that you mention from Who that Divines had to do with crime novels. I’m listening to them every night to fall asleep because I’m a crazy insomniac. There are always crime novels in my head. I was collaborating on one with Standard Schaefer. We both decided we had to rewrite our own version of the novel, so it’s a funny collaboration that fell apart, but not in a really negative way, in a hopefully creative way. It was very much a kind of noir crime novel, with the poetry also thinking through the materiality of clues and that kind of narrative, which is such an old narrative convention.

I love that idea of the materiality of clues, and I wonder if we could return to Irigaray and to the term “Divines” in this book’s title. You mentioned Tarot, collage, empathic collaboration, all of which make me think of “divine” as a verb. But when Irigaray calls for “divinity,” that seems more like a noun, a categorical state. And Who that Divines later posits an “I” whose life is “ruled by divination.” Could we parse divinity as fixed/metaphysical state, as experiential/exploratory practice, in your poetics?

I was fascinated by that quote because…

What does she mean?

I don’t actually have to believe in God. Because Buddha was a guy, and he wasn’t a god. Still Buddhism really is a religion, so as you get more into it you realize that it’s not just a philosophy. But one’s relationship to it doesn’t have to involve a Big Beard guy up in the sky, as Judeo-Christianity does. But, again, it is patriarchal in the same way that other religions are. So when Irigaray would say “divinity” I was like: seriously, we’re going to be a goddess? What does that mean? It seems so antithetical to me in a way. But then I liked that about it.

What I took it to mean, and I’m not sure if this is right…Irigaray believes that the fix is in in the language, so you can’t use this language and you can’t be in this culture and achieve anything like a kind of feminist good outcome. You are prevented from doing that by the very words that you are using and the very culture that you are in. I agree with that. And yet, if you recalibrate the sense of divinity, if you gradually go in this sort of direction, that’s a help. That was how I eventually made peace with that strangely annoying and grand statement. I enjoyed that assertiveness of it. And, as with me always, I enjoyed the various meanings.

Years ago Michael Palmer gave me a book about water divining, some old book that he must have randomly come across in a used book store and given to me I think as a birthday present. There’s a poem in Who that Divines, “The Modern Dowser,” that comes from this book. And there are still dowsers, which is interesting. Then there’s divination with the I Ching. I have always been drawn to methods of divination. I lived in San Francisco for 18 years, and when I would walk around I was always finding cards and fortunes. They would mean something in relation to my life. Recently I’ve gotten back to that. I’m part of a coven. It’s a very literary coven, but whatever. I felt implicated by all of those superstitions, but at the same time I’m the biggest skeptic ever. I’m a skeptical/superstitious person. When Jerry got sick (he died of cancer) I found that my relationship with cards and my relation with the fortunes I would find just collapsed. Because when you have something like that on your plate, you can’t find an ace of hearts and say “Well, everything’s going to be fine,” because it’s not. You realize that this sense of control, and this sense of chance being organized in some way (which we all have when we think about astrology or Tarot cards), is very hard to take into the ICU. I always say it’s very hard to take your Marxist critique into that place. In that intense place, you need something else, and I wouldn’t presume to say what it is for other people.

For one more autobiographical point of reference, here returning to Kazim’s interest in the autobiographical-seeming “An Air Force”: your father wants to talk about his recent war service, but you can’t hear it. An element of neo-memoir enters the work.

I think that’s true. I like memoir. I read it. I really enjoy memoirs by other people. It makes sense to do as you get older, not only because you’ve had this life but because there is a set of circumstances that is of interest to people to know. Although I like memoirs from very young people as well. I think memoir has value, in performing and sharing yourself with others. It celebrates the dead, and my parents have both passed. As you get older, people die. Of course, not only older people die, as I’ve learned. I was a video archivist before I worked at SPD. Because I was an archivist I was aware that we lose the archives. We think we have them, but we don’t. You just lose the past. One of the disadvantages of contemporary reading practices is that they tend to happen online and a bit on the run. I think younger people are less interested in the past than I was when I was young. But then I was odd in my interest in the past even among my own generation. I think that bringing that stuff into the present and writing it has a lot of value.

In terms of my own current reality, I’m very engaged with landscape, and with being out in nature as a part of it, and as a user/reader/interpreter/interrupter of nature. So I became obsessed with volcanoes. I have been trying to visit all of the Cascades over the past four or five years, and I was able to get to Iceland. Volcanoes aren’t just a landscape but an action, which is why the first section of my new book will be called “Glass Action.” The book itself will be called Personal Volcano. It has taken a long time to put it together. It’s finally making itself. Now it’s sort of avalanching forward, as opposed to me being stuck.